Uncategorized

Private Snafu

Beginning In 1943, Army recruits in World War II were introduced to a rubbery faced cartoon character named Private Snafu, a simpleton with a knack for trouble, that one writer described as “a model of everything, that, a model soldier isn’t.”

The cartoon was the mastermind of movie director Frank Capra, head of the first Motion Picture Unit of the U.S. Armed Forces, which produced highly stylized propaganda and training films that starred Hollywood actors like Clark Gable and Ronald Reagan.

But by far the most popular attraction, especially among the rank-n-file, was the bumbling Snafu.

Designed to teach proper etiquette in the Army, Snafu turned the tables on military protocol by humorously showing each enlisted man what not to do as a soldier.

Capra, who rejected Walt Disney for the contract (Disney reportedly wanted merchandise rights), chose Warner Brothers to make the films and “Bugs Bunny” animator Chuck Jones to produce it.

The shorts, all about 10 minutes in length, were exclusively the Army’s and not subject to standard motion picture codes. So Jones and his writers, including Theodore Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, were limitless in content, although they kept it mostly educational and entertaining at first.

In Spies, for example, Snafu forgets to take his Malaria medication and gets it – literally – in the end by a pesky mosquito. But that’s only part of the lesson. Snafu, who talks in rhymes, is on a pay phone: “Hello Mom, I’ve got a secret, I can only drop a tip. Don’t breathe a word to no one, but I’m going on a trip.” Eavesdroppers nearby, possibly spies, repeat the last line and soon an unsuspecting Snafu is blabbering his secret to anyone within earshot. Most of the shorts end with Snafu being killed by his own stupidity.

Later as the war neared an end, the shorts got edgier and Snafu smarter. Even the content became racier, with scantily clad or naked girls with body parts cleverly, but barely, disguised. About the only restraint remained in the explanation of the acronym, an unofficial military term: Something Normal All — Fouled Up, the announcer would say; a wink and a nod, of course, to its more popular interpretation.

The Mechanical Pencil

The Mechanical Pencil

In 1822, the first patent for a lead pencil that needed no sharpening was granted to two British men, Sampson Mordan and Isaac Hawkins.

A silversmith by trade, Mordan eventually bought out his partner and manufactured the new pencils which were made of silver and used a mechanism that continuously propelled the lead forward. When the lead ran out, it was easily replaced.

While Mordan may have marketed and sold the product as his own, the idea for a mechanical pencil was not a new one. In fact, its roots date back to the late 18th century where a refillable-type pencil was used by sailors on the HMS Pandora, a Royal Navy ship that sank on the outer Great Barrier Reef and whose artifacts including the predated writing utensil was found in its wreckage.

Mordan’s design notwithstanding, between 1822 and 1874, nearly 160 patents for mechanical pencils were submitted, which included the first spring and twist feeds.

Then In 1915, a 21-year old factory worker from Japan named Hayakawa Tokuji designed a more practical housing made of metal and called it the “Ever-Ready Sharp.”

Simultaneously in America, Charles Keeran, an Illinois businessman and inventor, created his own ratchet-based pencil that he similarly called “Eversharp” and was often mistaken for Tokuji’s design. Keeran claimed individuality and test marketed his product in department stores before submitting a patent. The pencil was so popular that Keeran had trouble keeping up with orders. To help with production, he partnered with the Wahl Adding Machine Company of Chicago.

It was not a good fit.

Keeran lost most of his stock holdings in a bad deal and was eventually forced out even though his pencils were making millions annually in sales.

Around the same time, in Japan, Tokuji’s factory was leveled by an earthquake. He lost nearly everything including some members of his family. So to start anew and settle debts he sold the business, began making radios instead and founded Sharp, named for the pencil, which still today is one of the largest electronics manufacturers in the world.

The Book Wheel

Image Posted on Updated on

By Ken Zurski

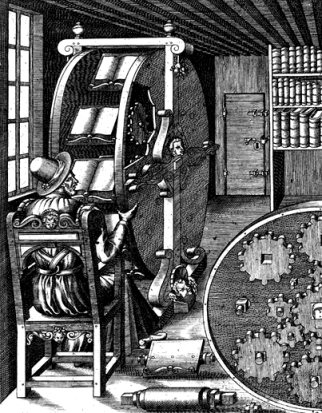

Agostino Ramelli was a military engineer, which meant he wore the armored suit and carried the sword, but used his brain rather than brawn on the battlefield.

This came in handy during the 16th century French Wars of Religion when the Italian born Ramelli went to France, took up arms with the Catholic League, and was captured by the Protestants (Huguenots). While incarcerated, Ramelli not only found a way to break out, but in as well. When he escaped – or was exchanged – Ramelli returned and breached the fortification by mining under a bastion.

From that point on, he called himself “Capitano” and dedicated his life to figuring things out.

In 1588, he released a book titled, Various and Ingenious Machines of Capitano Ramelli. The expertly illustrated book was a compilation of 195 machines that made laborious tasks more practical. Many of the machines lifted things in crafty ways, like water, or solid objects, like doors off their hinges. One machine milled flour using rollers rather than stones.

Then there was the Book Wheel.

“This is a beautiful and ingenious machine, very useful and convenient,” Ramelli wrote. By convenient, he meant for those suffering from gout, a painful joint disease which made walking or standing difficult. A noble gesture, for sure, but the wheel itself was six-feet in diameter. So its doubtful Ramelli designed it strictly for the disabled. Nevertheless, its usefulness is left up to the user to decide. The operator remains seated while the books, eight in all, each come to the front by turning the wheel.

Ramelli was especially proud of the gearing system that kept the books constantly level to the ground. He built an intricate gear for each slot and prominently featured a diagram in his book.

The impressive technology was similar to that used in an astronomical clock.

It was also wholly unnecessary.

A simple swivel pivot and gravity could do the trick just as engineer George Ferris would prove many centuries later in a similar design that carried people rather than books.

Speculation is Ramelli knew this, but as a mathematician, and a bit of a swank, couldn’t help himself.