Daniel Ackley’s Comic Strip Showcases Zurski’s New Book

Illustrator Daniel Ackley has featured Ken Zurski’s new book “Unremembered Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers and Influencers” in his comic strip series “Fred the Horse.”

“Fred the Horse” is described as a light-hearted comic strip about the misadventures of Fred The Horse down on the farm in Illinois.

In the strip, somehow Zurski’s book keeps getting into the hands of several characters that inhabits Ackley’s setting for “Fred the Horse.”

Daniel A. Ackley is a Peoria based artist, documentary filmmaker and entrepreneur. His comics appear in various newspaper publications and Peoria Magazine. See more of his work or contact Daniel Ackley at https://ackleytoon.com/ https://www.facebook.com/AckleyArt/

Order the book here: https://www.amikapress.com/books/unremembered-book-2

Exploring Dr. Seuss’s Whimsical Songwriting

By Ken Zurski

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, wrote dozens of children’s books that still today reach bestseller’s lists and thrill a new generation of fans each and every year. However, his work as a songwriter is often overlooked, due in part to the success of his books. But when reminded, the songs penned by Seuss, are just as enduring and whimsical.

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, wrote dozens of children’s books that still today reach bestseller’s lists and thrill a new generation of fans each and every year. However, his work as a songwriter is often overlooked, due in part to the success of his books. But when reminded, the songs penned by Seuss, are just as enduring and whimsical.

Seuss wrote the songs mostly for television animated specials. And if you know the shows, you know the songs. For instance, in The Cat in the Hat, a television short released in 1970, and based on his first children’s book of the same name, Geisel wrote several original songs including the bouncy, “The Gradunza” (The old, moss-covered, three-handled family gradunza), the catchy “Cat, Hat” (Cat, hat, in French, chat, chapeau. In Spanish, el gato in a sombrero.),” and the playfully teasing, “Calculatus Eliminatus” (Calculatus eliminatus always helps an awful lot. The way to find a missing something is to find out where it’s not), all with Seuss’s clever wordplay and sing-song rhyme pattern .

One song in particular, “I’m a Punk,” introduced such ridiculously pleasing locutions as crontunculous, gropulous, poobler, and schnunk. ” While everyone understands the meaning of punk, being a “schnunk” needed some explanation. But when the Cat sings, “nobody, likes me, not one tiny hunk,” everyone gets the idea.

One song in particular, “I’m a Punk,” introduced such ridiculously pleasing locutions as crontunculous, gropulous, poobler, and schnunk. ” While everyone understands the meaning of punk, being a “schnunk” needed some explanation. But when the Cat sings, “nobody, likes me, not one tiny hunk,” everyone gets the idea.

Some credit the Seuss writing style to a Life magazine article in 1956 that criticized children’s reading levels, specifically “primers” or textbooks with simplified words and phrases like “See Spot run” from the book series Fun with Dick and Jane. Geisel was asked to write a story using a vocabulary list of just over 200 words. He picked the first two words that rhymed, cat and hat, and went from there. It certainly wasn’t like any story in a textbook, that’s for sure, and critics praised “The Cat in the Hat” for its originality.

Several years later when Seuss wrote the lyrics for songs in his television specials, he seemed to relish the opportunity to ratchet up the silliness even more. Seuss’s words just seemed to work with music, oftentimes using traditional melodies, sometimes with an original score. The man credited with composing or arranging most of the music for Seuss is Dean Elliott, a Midwesterner from Wisconsin, who conducted orchestras for the Tom and Jerry shorts before hooking up with Seuss. Later Elliott worked with Bugs Bunny creator Chuck Jones.

Seuss’s most popular song is one we hear every year around the holidays. In it, an unmissable deep voice groans about the Grinch, a Seuss original, who has a “heart full of unwashed socks” and a “soul full of gunk.”

Seuss’s most popular song is one we hear every year around the holidays. In it, an unmissable deep voice groans about the Grinch, a Seuss original, who has a “heart full of unwashed socks” and a “soul full of gunk.”

Written in 1966 for the TV special “How the Grinch Stole Christmas,” Seuss enlisted a voice actor named Thurl Ravenscroft to sing the lead on the song even though Boris Karloff was the voice of the Grinch in the special. Karloff reportedly could not sing and Ravenscroft was hired . But Ravencroft’s name was never listed among the credits and Karloff mistakenly got most of the acclaim. Seuss was reportedly furious and apologized for the oversight. Ravenscroft was also the voice of Kellogg’s Tony the Tiger (They’re Great!).

“You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch,” is an unconventional Christmastime staple. The song never mentions Christmas, but rather teases with crafty metaphors, comparisons and contradictions all designed to point out what an awful crank the Grinch – now a symbol of holiday grumpiness – can be.

You’re a mean one Mr. Grinch

You really are a heel.

You’re as cuddly as a cactus,

And as charming as an eel,

Mr. Grinch!

The song is instantly recognizable, charming and unmistakably Dr. Seuss.

The songwriter.

The Real History Behind Black Friday: the Day and that Song

By Ken Zurski

Before Americans began rushing to stores the day after Thanksgiving and calling the shopping frenzy “Black Friday,” the term itself was used to describe a dark and devious part of our nation’s history.

One that was mostly forgotten until 1975 when a group named Steely Dan immortalized it in song. But still to this day. most people don’t know what the song is really about:

“When Black Friday comes

I stand down by the door

And catch the grey men when they

Dive from the fourteenth floor”

Here’s the story:

The original “Black Friday” begins with a man named Jay Gould.

A leather maker turned New York railroad owner, Gould was the youngest of six children, the only boy, and a scrawny one at that; growing up to be barely five feet tall. What he lacked in size, however, he made up for in ambition.

A financial whiz even as a young man, Gould started surveying and plotting maps for land in rural New York, where he grew up. It was tough work, but not much pay, at least not enough for Gould. In 1856 he met a successful tanner – good work at the time – who taught Gould how to make leather from animal skins and tree bark. Gould found making money just as easy as fashioning belts and bridles. He found a few rich backers, hired a few men and started his own tanning company by literally building a town from scratch in the middle of a vacant but abundant woodland. When the money started to flow, the backers balked, accusing Gould of deception. Their suspicions led to a takeover. The workers, who all lived quite comfortably in the new town they built and named Gouldsborough, rallied around Gould and took the plant back by force, in a shootout no less, although no one was seriously hurt.

Gould won the day, but the business was ruined. By sheer luck, another promising venture opened up. A friend and fellow leather partner had some stock in a small upstate New York railroad line. The line was dying and the stock price plummeted. So Gould bought up the stock, all of it in fact, with what little earnings he had left, and began improving the line. Eventually the rusty trail hooked up with a larger line and Gould was back in business. He now owned the quite lucrative Erie Railroad.

Ten years later, in 1869, Gould turned his attentions to gold.

When Black Friday comes

I collect everything I’m owed

And before my friends find out

I’ll be on the road

Gold was being used exclusively by European markets to pay American farmers for exports since the U.S currency, greenbacks, were not legal tender overseas. Since it would take weeks, sometime months for a transaction to occur, the price would fluctuate with the unstable gold/greenback exchange rate. If gold went down or the greenback price went up, merchants would be liable -often at a substantial loss – to cover the cost of the fluctuations. To protect merchants against risk, the New York Stock Exchange was created so gold could be borrowed at current rates and merchants could pay suppliers immediately and make the gold payment when it came due. Since it was gold for gold – exchange rates were irrelevant.

Gould watched the markets closely always looking for a way to trade up. He reasoned that if traders, like himself, bought gold then lent it using cash as collateral, large collections could be acquired without using much cash at all. And if gold bought more greenback, then products shipped overseas would look cheaper and buyers would spend more. He had a plan but needed a partner.

He found that person in “Gentleman Jim Fisk.”

Jim Fisk was a larger than life figure in New York both physically and socially. A farm boy from New England, Fisk worked as a laborer in a circus troupe before becoming a two-bit peddler selling worthless trinkets and tools door to door to struggling farmers. The townsfolk were duped into calling him “Santa Claus” not only for his physical traits but his apparent generosity as well. When the Civil War came, Fisk made a fortune smuggling cotton from southern plantations to northern mills.

So by the time he reached New York, Fisk was a wealthy man. He also spent money as fast as he could make it; openly cavorted with pretty young girls; and lavished those he admired with expensive gifts and nights on the town. Fisk never hid behind his actions even if they were corrupt. He would chortle at his own genius and openly embarrass those he was cheating. He earned the dubious nickname “Gentleman” for being polite and loyal to his friends.

Fisk and Gould were already in the business of slippery finance. Besides manipulating railroad stock (Fisk was on the board of the Erie Railroad), they dabbled in livestock and bought up cattle futures when prices dropped to a penny a head. Convinced they could outsmart, out con and outlast anyone, it was time to go after a bigger prize: gold. There was only $20 million in gold available in New York City and nationally $100 million in reserves. The market was ripe for the taking and both men beamed at the prospects.

When Black Friday falls you know it’s got to be

Don’t let it fall on me

But the government stood in the way. President Grant was trying to figure out a way to unravel the gold mess, increase shipments overseas and pay off war debts. If gold prices suddenly skyrocketed, as Gould and Fisk had intended, Grant might consider a proposed plan for the government to sell its gold reserves and stabilize the markets; a plan that would leave the two clever traders in a quandary.

Through acquaintances, including Grant’s own brother-in-law, Gould and Fisk met with the president. In June of 1869, they pitched their idea posing as two concerned (a lie) but wealthy (true) citizens who could save the gold markets and raise exports, thus doing the country a favor. They insisted the president let the markets stand and keep the government at bay. Fisk even treated the president to an evening at the opera – in Gould’s private box. The wily general may have been impressed by the opera, but he was also a practical man. He told the two estimable gentlemen that he had no plans to intervene, at least not initially. But Grant really had no idea what the two shysters were up to.

A few months later, when Fisk sent a letter to Grant to confirm the president’s steadfast support, a message arrived back that Grant had received the letter and there would be no reply. The lack of a response was as good as a “yes” for Fisk. Grant was clearly on board, he thought.

He was wrong.

“When Black Friday comes

I’m gonna dig myself a hole

Gonna lay down in it ’til

I satisfy my soul”

On September 20th, a Monday, Fisk’s broker started to buy and the markets subsequently panicked. Gold held steady at first at $130 for every $100 in greenback, but the next day Fisk worked his magic. He showed up in person and went on the offensive. Using threats and lies, including where he thought the president stood on the matter, Fisk spooked the floor.

The Bulls slaughtered the Bears.

Gold was bought, borrowed and sold. And Fisk and Gould, through various brokers, did all the buying. On Wednesday, gold closed slightly over 141, the highest price ever. In his typical showy style, Fisk couldn’t help but rub it in. He brazenly offered bets of 50-thousand dollars that the number would reach 145 by the end of the week. If someone took that sucker proposition, they lost. By Thursday, gold prices hit an astounding 150. The next day it would reach 160.

Then the bottom fell out.

At the White House, Grant was tipped off and furious. On September 24, a Friday, he put the government gold reserve up for sale and Gould and Fisk were effectively out of business. Thanks to the government sell off, almost immediately, gold prices plummeted back to the 130’s. Many investors lost a bundle, but the two schemers got out mostly unscathed.

The whole affair became famously known as “Black Friday.”

When Black Friday comes

I’m gonna stake my claim

I guess I’ll change my name

In 1975, Steely Dan, the rock group consisting of multi-instrumentalist Walter Becker and singer Donald Fagen, wrote a song about it. “Black Friday” was released that same year on their “Katy Lied” album. It was the first single off the album and reached #37 on the Billboard charts.

The song is about the 1869 Gould/Fisk takeover but confuses some listeners due to it’s reference to an Australian town named Muswellbrooke (“Fly down to Muswellbrook”) and the line about kangaroos (“Nothing to do but feed all the kangaroos”).

Fagen later confirmed in an interview the town name was added by chance: “I think we had a map and put our finger down at the place that we thought would be the furthest away from New York or wherever we were at the time. That was it.”

Today the term “Black Friday” is referenced in relation to the Friday after Thanksgiving, traditionally the busiest shopping season of the year and the day retailers go “in the black,” so to speak.

Steely Dan had none of that in mind when they wrote the song.

(“Black Friday” written by Donald Jay Fagen, Walter Carl Becker • Copyright © Universal Music Publishing Group)

Robert Crowe: The Lawyer Behind Chicago’s Infamous Trials

By Ken Zurski

Robert Emmitt Crowe was born in Peoria, Illinois on January 22, 1879, the last of eight children to Patrick and Annie Crowe, Irish immigrants who came to America in the mid-1800s. The large Crowe clan would only know Peoria for a short time. Before he was of school age, his father, a gas lamp lighter for the city, moved the family to Chicago, where Robert would begin a career in law.

Soon Robert Crowe would become the city’s top prosecutor, known today for a classic showdown with famed Chicago defense attorney Clarence Darrow.

There are no books written specifically about Robert Crowe, but there are plenty about Darrow. The authors of these books do not diminish Crowe’s role as Darrow’s antagonist, nor his short upbringing in Peoria—which, as it turns out, was a tumultuous one for the Crowe family.

The Investigative Imagination

During the Irish potato famine of the 1840s, Patrick Crowe emigrated to the U.S., as did many others from the County Galway region. Crowe carried a grudge against the British government and soon joined a group of Irish nationalists known as the Fenian Brotherhood, whose goal was to free Ireland from British rule.

Bombs went off in London and other key British cities. Then on May 6, 1882, a British royal named Lord Frederick Cavendish and his under-secretary were ambushed and gunned down in a Dublin park. The assassination was tied to radical Irish groups both in Europe and abroad. Soon, the investigation reached America.

Fenian chapters were active in cities like Peoria, where Crowe was a member. Shortly after the British bombings, a zealous group of reporters saw Crowe carrying a tin can on his rounds lighting the lamps. “Suppose that can in his hand was really a bomb to be thrown at the King of England?” they speculated. They became convinced (possibly influenced by alcohol, as one report goes) that Crowe was behind the bombings—and possibly the assassination, too. As the Peoriana notebook put it years later: “The imagination of the news hounds began working.”

A wire story was sent out, and Crowe became international news. “Dynamite Crowe” became his moniker in the headlines. Even detectives from Scotland Yard arrived in Peoria to follow his every move.

Crowe never shied away from his hatred of British policies and even fueled speculation by bragging about Fenian-financed, dynamite-making factories in Peoria and New York. In the end, his reported arrest in Peoria by the U.S. Marshall was fabricated, and the “hoax,” as it would be called, dropped out of the news. But it’s the reason Patrick Crowe left Peoria.

A Crime in Chicago

To the Clan na Gael—the Irish activist group which replaced the Fenian Brotherhood—Crowe was a hero, and they invited him to Chicago. The family moved from Peoria to Chicago’s 19th Ward, a poor neighborhood made up of mostly Irish immigrants.

Robert was only three at the time. He attended Chicago public schools, graduated high school and studied law at Yale University. In 1903, he returned to Chicago and opened a private practice, and his political aspirations eventually led to an appointment on the bench as a criminal court judge.

Described as “jut jawed and thin-lipped, with a steady gaze and intimidating manner,” Crowe was elected Cook County state’s attorney in 1920. Fighting corruption, even in government, was the key to his victory. “The real reason for his failure,” Crowe said of his opponent that year, “is that he is guilty and knows it.”

Crowe is best remembered as the prosecutor in the May 1924 murder trial of 14-year-old Bobby Franks. Two University of Chicago students named Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb—both 19 and from wealthy families—were arrested and charged with the crime. They confessed to abducting Franks, killing the boy and dumping the body in a forest preserve. Clarence Darrow, who had a reputation for defending the defenseless, was hired to take on the case. “It never occurred to me that I would refuse to defend anyone,” he once said.

By admitting they had killed Franks “for the thrill of it,” Leopold and Loeb were guilty… but of what punishment? The city was captivated by the senseless murder and subsequent trial. For a full month, they followed every word.

Crowe, who had a reputation for being tough on crime, pushed for the death penalty, but Darrow pushed back. He believed capital punishment did nothing to prevent crimes like these. Impulse, not fear, Darrow argued, guided violent tendencies. But a frustrated Crowe would have none of it. “The only useful thing that remains for them now is to go out of this life and to go out of it as quickly as possible,” he demanded.

Darrow would win the argument. Leopold and Loeb’s lives were spared, and both received life imprisonment sentences instead.

Crowe was left to ponder whether the outcome was “a repudiation of his hang ‘em high brand of justice,” as one author put it.

The Legacy of Kodak’s Autographic Camera

By Ken Zurski

In 1914, Eastman Kodak Company introduced a new line of cameras that not only took a picture but recorded the date and title as well. Actually, the date and title was up to the picture taker to record, but nonetheless as Kodak advertised, “any negative worth the making is worth the date and title.”

Kodak called it an “autographic camera” and here’s how it worked: A special film was used that contained a small piece of tissue carbon between the film and the paper backing. A little window on the back of the camera would be opened and with a metal stylus the text could be written on the carbon. The window was left open briefly for exposure and when the pictures were developed, the notation would be visible between the prints. “These notations add to the value of every picture you make,” Kodak insisted.

Jacque Gaisman, a French-American who invented the safety razor, is credited with the concept. He sold it to George Eastman for $300,000. Eastman had high hopes for the new technology, but it never caught on.

Still, it has its place in history. In 1924, British mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine were lost and presumed dead on Mount Everest during Mallory’s fourth attempt to become the first person to reach the elusive summit. Mallory had brought a photographer along, a man named John Noel who used a motion picture camera that weighed 40 pounds.

Mallory, however carried a smaller Kodak vest camera which had the autographic feature. The camera was believed to be on Mallory when he and Irvine vanished.

In 1999, an American climbing team tracing Mallory’s steps discovered the famous climber’s frozen corpse. They were hoping to find the camera too. Perhaps it could tell the tale of Mallory’s last days.

But the camera was missing.

Speculation is Mallory gave it to Irvine to take pictures of him reaching the summit before perishing on the Northeast edge. But no one knows. In 2024, A Chinese documentary team found a boot, with remains, believed to be Irvine’s foot, but no camera was found.

13,000 Words. The Gettysburg Speech before Lincoln’s Address

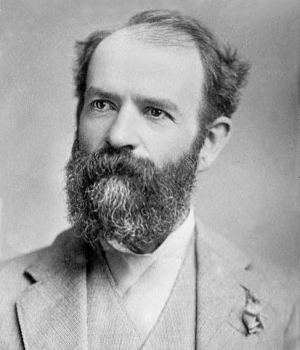

“Senator Edward Everett had spent his life preparing for this moment,” wrote historian Ted Widmar in “The Other Gettysburg Address.” “If anyone could put the battle into a broad historical context, it was he. His immense erudition and his reputation as a speaker set expectations very high for the address to come.”

Indeed, as Widmar implied, Everett knew the moment was an important one for the country. He was on the battlefield of Gettysburg, now a makeshift graveyard, soon to be the nation’s first national cemetery.

It was November 19, 1863.

He began: “Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature. But the duty to which you have called me must be performed;–grant me, I pray you, your indulgence and your sympathy.

Two hours and 13,000 words later he was done: “I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country there will be no brighter page than that which relates the battles of Gettysburg.”

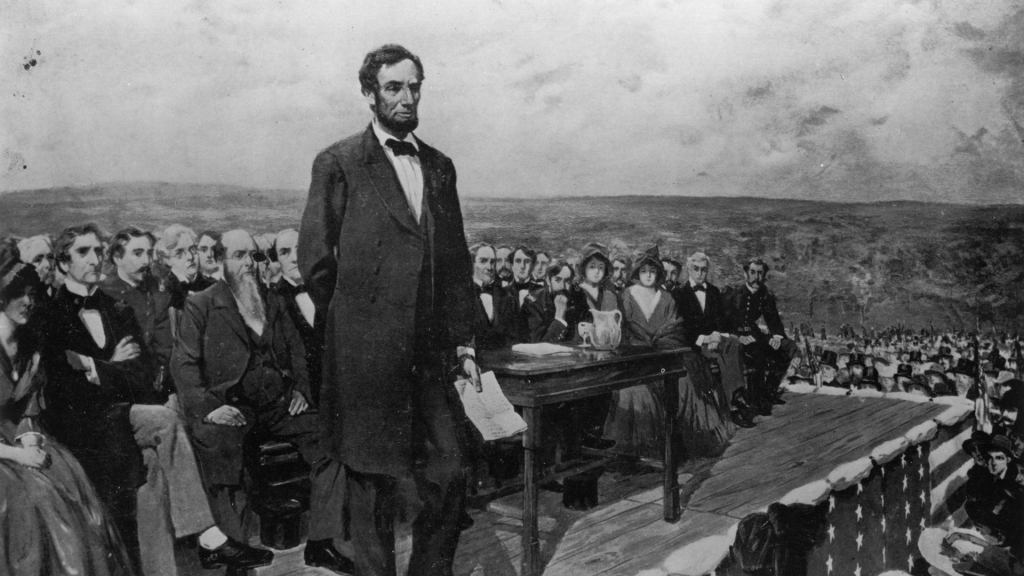

Widmar wrote: “As it turned out, Americans were correct to assume that history would forever remember the words spoken on that day. But they were not to be his. As we all know, another speaker stole the limelight, and what we now call the Gettysburg Address was close to the opposite of what Everett prepared.

Lincoln spoke: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal….”

When Lincoln ended, it was hardly an address. “Simply the musings of a speaker with no command of Greek history, no polish on the stage, and barely a speech at all – a mere exhalation of around 270 words,” Widmar explained.

It was over in just two minutes.

“Everett’s first sentence, just clearing his throat, was 19 percent of that – 52 words,” Widmar remarked.

The next day , Everett sent Lincoln a note: “Permit me also to express my great admiration of the thoughts expressed by you, with such eloquent simplicity & appropriateness, at the consecration of the Cemetery. I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” he wrote.

All Hail Coffee Soup! Wait…What?

By Ken Zurski

The Amish culture goes back to Old German Anabaptist roots in the 16th century and is defined today by the simple and private lifestyle of those who follow it. The horse-and-buggy transportation is the most recognizable of the Amish culture followed by the modest and similar clothing that includes a vest and hat for men and a plain three-piece dress, cape, apron and bonnet for women.

As for cooking, a variation of grains, dairy and meats are usually on the menu and water mostly to drink, with milk, coffee and tea too. Coffee can be served in the evening with – or as – a good dessert.

So what’s up with one dish, now specifically identified as Amish influenced, and named coffee soup?

That’s right…coffee with the word soup.

The Amish had a stable lifestyle but also struggled some during the Great Depression. So less was more and soups were at least a meal. You can make a lot of it and even save it for several meals across several days.

Thus was born coffee soup. Or so it seems.

There are few ingredients in coffee soup that start with a brewed coffee base, preferably a dark roast. Then add sugar and cream. For substance, a piece a grain bread cut in pieces or put in whole is added. Each spoonful then gets a chunk of bread and the taste of sweet coffee. It’s served cold, mostly. In more recent times, saltines can replace the bread and in some instances cheese is added.

Of course spices, like cinnamon or something more savory, might be added too, but it’s origins with just three to four simple ingredients are at it’s core.

Ready to try it.

Coffee soup.

Guten Appetit!

(Photo courtesy of Amish365.com)

The Eccentric Speech That Forecasted the Great Chicago Fire

By Ken Zurski

On October 7, 1871, George Francis Train a businessman and self-proclaimed inventor, spoke in front of a large audience at a lecture hall in Chicago.

Train had just returned from traveling around the world in 80 days (later claiming to be the inspiration for Jules Verne’s fictional character Phileas Fogg) and was on a speaking tour to support a run for President of the United States or as he called it “Dictator of the USA.”

But in Chicago, he delivered a stunning speech. “This is the last public address that will be delivered within these walls.” He told the crowd. “A terrible calamity is impending over the City of Chicago.”

Train’s reputation as an eccentric preceded him. While alarming, his prophesying was quickly forgotten. The next day however, a fire broke out that devastated the city.

The Chicago Times was first to report Train’s speech claiming he was part of a fringe group based in Paris, with off-shoot chapters throughout the world, including Chicago. The article asserted the group, Societe Internationale, could not accomplish what they desired – labor unity- by peaceful means and that the “burning of Chicago” was suggested. The other newspaper in town, the Chicago Evening Journal, debunked such claims and blasted the Times for concocting a communist plot against the city.

Train, however, had some explaining to do. He did by claiming his doomsday prediction was actually in response to shifty government policies that left a crowded, neglected city and its infrastructure prone to a disaster – either by flood or fire. The timing, he said, was purely coincidental.

As for the cause of the blaze, the papers soon found another scapegoat – and a sensationalist story to boot – in a diary cow, a lantern and the unsuspecting wife of a saloon owner named Patrick O’Leary.

Historically – and Tragically – April 15 is More Than Just Tax Day

By Ken Zurski

Tax Day, April 15, used to be a big deal.

That’s because years before the internet and e-filing made doing your taxes more convenient, those who owed taxes ostensibly waited until the end of the last day to file their returns.

For some it was symbolic, even if you were due a refund.

So local post offices prepared for the onslaught.

In larger cities smiling postal employees set up a drive through service to allow the so-called “procrastinators” to pull up and simply drop off their returns without even getting out of their vehicles.

But today, because it’s easier to file returns online, the absurdity of dropping tax returns off at the last minute seems pointless. So the colloquial term Tax Day, or April 15, just doesn’t have the same impact as it did years ago.

But historically, the date of April 15 is known for two tragic events.

More recently, in 2013, the Boston Marathon bombing occurred on April 15. The other is from 1912, ironically a year before there was a federal income tax. In that year, on that fateful April day, an ocean liner, the largest of its kind for the day, sank after striking an iceberg in the Atlantic Ocean. “A Night to Remember” as author Walter Lord famously put it is his book about the tragedy.

Yes, the sinking of the Titanic was on April 15.

Additionally, President Abraham Lincoln officially died on April 15, 1865 a day after being shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater.

Understandably, because of its significance for all Americans, April 15, is more associated with taxes, than tragedy. But even the date itself isn’t always ceremonially the last day to file taxes. If the 15th day of April is on a weekend, then the following Monday and Tuesday, either the 16th or 17th, is designated as the national day of filing. And today, if you don’t get your taxes in by the deadline date, just go online and file an automatic extension. Anybody can do it.

So much for a designated Tax Day.

Maybe it’s time to give April 15, the date, back to history:

Remember the Titanic!

Boston Strong!

Discovering the Roots of Mrs. Claus in The Christmas Legend

By Ken Zurski

“The Christmas Legend” is a short story written in the mid-nineteenth century by a Philadelphia missionary named James Rees. It tells the tale of a destitute American family that receives an unexpected visit from a couple of strangers on Christmas Eve. The constructive narrative sets up a deep exploration of family, loss and forgiveness; a classic Christmas formula.

Published in 1849, “The Christmas Legend” was part of a collection of 29 short stories written by Rees and compiled under the title, “Mysteries of City Life, or Stray Leaves from the World’s Book.” Each story is cleverly presented to represent the dissimilarity of many leaf types. For example, the maple leaf, Rees writes, is “golden and rich” and presents a sunnier disposition, while another like the gum tree leaf has a “bloody hue” and “stands fit emblem of the tragic muse.” He likens authors after the “forest trees” which “send forth their leaves unto the world.”

“And by what emblem shall we appear amongst those clustering trees,” Rees explains. “Let us see – Ah! The Ash Tree leaves are like ours, humble and plain to see, but hiding the silver underneath.”

In “The Christmas Legend,” Rees uses the spirit of the holiday to emphasis this point.

Here is the abbreviated story…

A family of four, mother and father, daughter and son, are sitting near the fireplace on Christmas Eve. The two children, especially the daughter, wonders if she should hang the stockings for Kris Kringle to come. But her mother raises doubt. There are more important things in life than earthly possessions, she states: “Poverty keeps from the humble door all the bright things of the earth, except virtue, truth and religion, these are more of heaven and earth, and are the poor man’s friend in time of adversity.”

“I thought that Santa Claus or Kris Kringle loved all those who are good, and haven’t I been good?” the daughter asks confused.

The mother tells her to leave the stocking up. “Customs at least should be observed, and perhaps the young heart may not be disappointed,” she explains.

The father is more introspective. He anguishes over a lost family member, the eldest child, another daughter who apparently ran away with a “dissipated” man seven years before and hasn’t been seen or heard from since.

Then there is a knock at the door.

Two strangers appear out of the night, an elderly couple carrying a bundle with “all their worldly wealth.” They ask how far away they are from the city and the father tells them it is “two miles.”

“Two miles?” the stranger says sadly, “we will not be able to reach it tonight. My dear wife is nearly tired out. We have traveled far today.”

The father invites them in and offers his best bed for them to rest. The strangers inquire if this is their whole family. “No. No,” the father says, “we had one other – a daughter.”

“Dead; Alas we all must die,” the old woman responds.

“Dead to us,” the man answers. “But not to the world. But let us speak of her no more. Here is some bread and cheese, it is all poverty has to offer, and to it you are heartily welcome.”

There is a silent pause, then the sound of cheerful merriment, music and laughter, is heard through the open windows and doors. It’s their rich landlord, the father explains, mocking the poor. The old man interjects. “Ah, sir, human nature is a mystery, this is one of the enigmas, and can only be explained when the secrets of the hearts be known.”

The next morning, Christmas Day, the family awakes to find their small room filled with presents: books and games and toys. “O Father, Kris Kringle has been here,” the little girl says excitedly. “I am so happy.”

Here Rees as the narrator sets up the moral of the story. “There are moments when the doors of memory and the bright sunshine of hope make the future all clear,” he writes. “Sorrow is not eternal; it has its changes, its stops; its antidote; they came in the moment of trial and – Presto! The whole scene of life is venerated in the pleasing colors of fancy.”

And that’s when something totally unexpected occurs. The old couple reappears to the family not as as they came, but as a vibrant young couple. The children recoil from fright, but the parents are curious. “How is this?” the father asks. “Why these disguises —“

“Hush, sir,” the once old man says laughing. “This is Christmas morn and we now appear to you not as Santa Claus and his wife, but as we are, the mere actors of this pleasing farce.”

The couple recognizes the old woman’s new face. It’s their long lost daughter. The girl hugs her mother, but the father is more skeptical, angry and weary of atonement. He lashes out at the girl as she approaches him. “Stand back!”, he shouts, then chastises the man who stands with her as a “paramour.” She begs him to reconsider. “No Father he is my kind and affectionate husband.”

“Ah, husband,” the father replies. He reaches for his daughter. They embrace.

Rees goes on to explain the girl ran away because she was “young and foolish” but loved the man who was forbidden from her home. They left America for England where her new husband became heir to a large estate. She sent letters home, but they were never received. Now she had returned back to her family on Christmas Day. A gift of love and hope. “Can you forgive me?” she asks.

“Say no more, all is forgotten. All is forgiven,” the father tells her.

Even though it is thinly defined, the mention of Santa Claus’s wife in “The Christmas Legend” is widely considered the first ever to appear in print. Two years later in 1851, the name Mrs. Santa Claus would be mentioned again in a story published in the Yale Literary Magazine. History tells the rest.

Today, Mrs. Claus is considered a kindly old woman who helps her husband on Christmas Eve, tends to his colds, stitches his clothes, and feeds his “round belly,” usually with homemade cookies and milk.

“There are many interesting facts both historic and fabulous connected with the ceremonies, customs and superstitions of this day [Christmas],” Rees explains in the introduction to his tale, “which if collected together today would make and curious and interesting book.”

The End of the 1970’s was Both a Good and Bad Time for the Music Industry

By Ken Zurski

The end of the 1970’s, specifically the end of 1979, was both a very good and very bad time for music lovers.

First the good. Two albums – both double disc packages – were released only weeks apart from each other that even today are still considered two of the most influential albums of all time. But the end of the decade was also a tragic and sad one for the music industry when a deadly incident at a rock concert both shocked and angered a nation.

The two albums were both indirectly involved in the grief and healing that would follow.

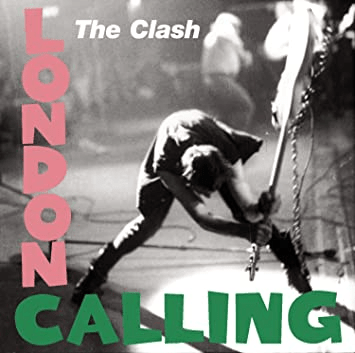

Released in the final months of 1979, and due to their late arrival that year, both albums are widely considered to be successes in the 1980’s instead. (Note: “London Calling” was released in the UK in December 1979; in the US it was released on January 10, 1980). Regardless of which decade they belong, both have a place in rock n roll history and both deserve recognition for being musically experimental and risky too – after all they were double albums, meaning you got double the music in one package.

In retrospect, the timing was perfect. The 70’s was a turbulent decade for music. While hard rock and arena rock gained prominence in the 70’s, the rise of disco was eventually seen as a threat to rock fans, whose mainstay bands like the Rolling Stones dabbled in the genre of dance music (“Miss You”). The decade started with the break up of the Beatles and ended tragically with that unimaginable and deadly concert disaster.

Despite this, the 80’s was looming and rock needed a boost.

It came from the two albums by The Clash and Pink Floyd, respectively.

On December 14, 1979, the British group The Clash released their third album titled “London Calling.” The album cover itself was striking. It featured an action shot of bassist Paul Simonon holding a guitar by the neck and ready to smash it to pieces. It captured a moment of pure rock n roll explosiveness. It also conveyed the group’s reputation as rebellious and unflinching.

The album sold as expected, reaching #27 on the US Billboard charts, and doing even better overseas. Critics adored it calling it a “masterpiece” and placing it on Top Ten lists of the year for both 1979 and 1980.

As albums go, before the digital age, it is considered a work of genius, conceptually too. Most double albums seemed overextended and unnecessary. “London Calling” was different. It was a complete work of art, from the music to the package. And that cover? Iconic. And although music itself is always subjective, most rock historians agree, “London Calling’ is a classic in the true sense of the word. Today, it is the 6th most ranked record on critics’ lists of the all-time greatest albums according to Acclaimed Music. The Clash would go on to have bigger selling albums and singles, but for both musicianship and inventiveness, “London Calling’s” legacy is solid.

Before “London Calling” dropped, however, another double album was released. Unlike the Clash’s dramatic action shot on the cover, the front of this album was simple in design: a drawing of a white brick wall. But that was it. There was no writing on the wall, so to speak. If not for a transparent naming sticker attached to the cover, there was no other way of knowing who was responsible until you turned the album around.

The band, of course, was Pink Floyd and the work was appropriately titled, “The Wall.”

Pink Floyd was an established band, known for its conceptual albums and “The Wall,” their 11th release, was no exception. It was however, their first double LP and the reaction to its apparent expansiveness was mixed. “I’m not sure whether it’s brilliant or terrible, but I find it utterly compelling,” was the response from Melody Maker.

Despite the tepid response from critics, the album was a instant best seller, topping the charts in multiple countries, including the US.

Today, it is considered a classic that has stood the test of time. Several songs like “Another Brick in The Wall Part II” and “Comfortably Numb,” are rock radio staples and a movie of the album’s concept about a drugged out rock n roller who figuratively builds a wall around his troubled life, was released in 1982. Recent year tours of “The Wall,” with varying members of the band participating, are huge successes It still has legs, they say in the business.

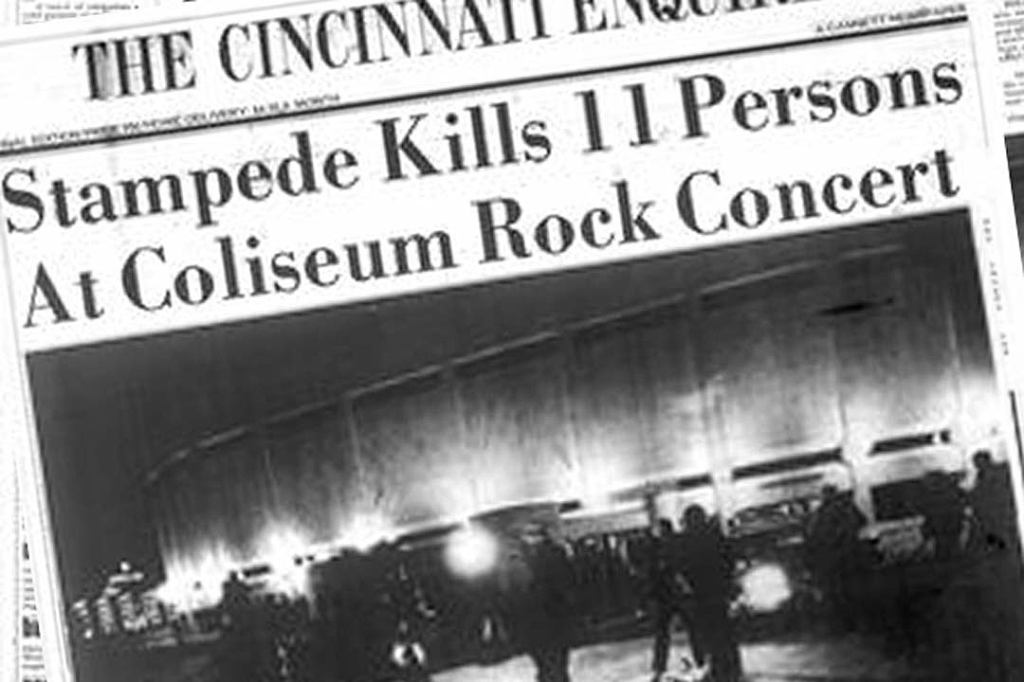

The album’s initial release in late November, however was marred by tragedy when on December 3, 1979, eleven people were killed, crushed to death in a stampede, before a Who concert in Cincinnati. Just days before, in reviews, the comparisons of the dark and satirical “The Wall” to the Who’s classic double album rock opera “Tommy” was justified, but purely coincidental, considering the circumstances.

The Who were not held directly responsible for the deaths of the concertgoers, but it didn’t matter. The industry as a whole took a hit. After the tragedy, the rock world paused to mourn, reflect, regroup, and eventually move on.

Pink Floyd’s “The Wall” was a part of that.

A week later, on December 14, The Clash’s “London Calling” was released.

Bring on the 80’s.

A Christmas Song written by a US Presidential Candidate and Once Covered by Gene Autry is Forever Immortalized in a Cartoon Short

By Ken Zurski

In 1951, cowboy crooner Gene Autry released a song titled “The Three Little Dwarfs,” that playfully told the story of three “helpers” trusted by Santa to “drive” his sleigh on Christmas Eve.

The song was written by Stuart Hamblen, a singer, songwriter and politician who ran for President of the United States in 1952 on the Prohibition Party ticket. “A cowboy singer, former racehorse owner and converted alcoholic,” Time magazine wrote that year about Hamblen who picked up 73,000 votes, second most by a third party candidate.

Before politics, the Texas born Hamblen was known for being one of the first singing cowboys and in the 1930’s hosted a popular radio show called “Family Album.”

Hamblen wrote several hits for country radio but nothing quite as enduring as “The Three Little Dwarfs.”

The most famous singing cowboy, Gene Autry recorded the song and released it as a single with a B side tune titled “32 feet – 8 Little Tails.” In December 1951, Columbia Records ran an ad in Billboard listing the label’s “best sellers.” Autry’s “The Three Little Dwarfs” was listed just ahead of his version of “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer.”

Today, Autry’s version of “Rudolph” is considered a holiday staple, while “The Three Little Dwarfs” is mostly forgotten.

The song itself however is not.

It was immortalized in a two-minute stop-animation cartoon titled “The Three Little Dwarfs,” but more commonly known as “Hardrock , Coco and Joe.”

Oh-lee-o-lay-dee, o-lay-dee-I-ay

Donner and Blitzen, away, away

Oh-lee-o-lay-dee, o-lay-dee-I-oh

I’m Hardrock! I’m Coco! I’m Joe!

The short premiered on Chicago’s WGN-TV on Christmas Eve 1956.

Autry’s song was not the one used in the short. The tune was re-recorded and reworked. For instance, a narrator is used to speak some of words rather than sing them.

But the most recognizable difference was in Joe’s line. In Autry’s rendition, Joe is sung in a high-pitched voice rather than the distinctive and memorable deep bass of “I’m Joe” featured in the animated version.

Share this:

Courier Newspapers Feature Ken Zurski’s Latest ‘Unremembered’ Book

Local author Ken Zurski releases ‘UNREMEMBERED’ sequel

By Madelyn Norman from Courier newspapers

Ellen Terry. Charles Klein. Gaby Deslys. These are names you probably haven’t heard, with stories you won’t forget. In Ken Zurski’s latest “UNREMEMBERED Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers & Influencers,” he shares the history of souls that made all the difference, but go rather unnoticed.

In his sequel, published in September, Zurski shares the attempts and accomplishments of people in the entertainment industry between the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The “UNREMEMBERED” series first began as a blog, unrememberedhistory.com, which now has over 200 stories of forgotten people throughout history. Zurski realized he was able to intertwine these stories in the form of a nonfiction book, utilizing records of the past.

“I wanted to find a story where I could connect things together,” he said. “We have history to tell because someone else told it before.”

As the author of four books, Zurski has been sharing history since his first book, “The Wreck of the Columbia,” which was published in 2012. As a resident of Morton, Illinois, he loves telling regional stories that made a lasting impact on the people reading them. “UNREMEMBERED” allowed Zurski to branch out into global storytelling.

The prevalence of digital databases and online resources allowed Zurski to gather information at a much quicker rate, which made writing the “UNREMEMBERED” books more enjoyable.

“Research has become much more advanced–thank goodness,” Zurski said. “When I wrote ‘The Wreck of Columbia’ I was at the Peoria and Pekin libraries for days on end, going through their newspaper archives.”

Although researching and writing is a time-consuming process, Zurski wouldn’t trade it for anything.

“It’s really my joy, just writing books and sharing them,” he said.

Since “UNREMEMBERED Book 2” is centered around people that most readers are unfamiliar with, Zurski has a recommendation for the best way to read his book.

“Look at the back of the book first and see if you recognize any names,” Zurski said. “Read the book. Come back to it–and you’ll have all of these stories.”

Visit amazon.com or amikapress.com to purchase a copy of “UNREMEMBERED Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers & Influencers.”