History

The Fascinating Backstory of ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’

By Ken Zurski

In 1904, actor, singer, songwriter George M. Cohan, an avid baseball fan, was checking the latest scores in the newspaper when he came across the story of an American horse jockey who was winning big races in England.

Tod Sloan, a kid from rural Indiana, was flourishing on the British turf thanks to a radical forward leaning crouch, an old quarter horse stance, which Sloan did not invent, but perfected.

Cohan had an idea.

He wrote a musical based loosely on Sloan’s racing success and reputed playboy lifestyle.

Less than a year later, “Little Johnny Jones” premiered on Broadway.

The critics were kind. “It is action and life from start to finish,” raved one reviewer. Cohan had a crowd pleaser for sure, But one song seemed to resonate more than others.

Known affectionately as the “Yankee Doodle Comedian” thanks to being born on July 4th (1878), Cohen was actually born the previous day, but his father, a rabid flag-waver, fudged on the date. Cohan embraced the patriotic connotation and rarely corrected those who questioned it. He wrote the song “Yankee Doodle Boy” for the Johnny Jones character, but clearly with an autobiographical bent.

“A real life nephew of my Uncle Sam’s.” the song went, “Born on the Fourth of July.”

Many years later in 1942, James Cagney played Cohan in a movie about making a musical. Cagney made the song immortal by dancing and singing an even more patriotic version called “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy

A Yankee Doodle, do or die!

How the Sporting Goods Makers Helped the War Effort

By Ken Zurski

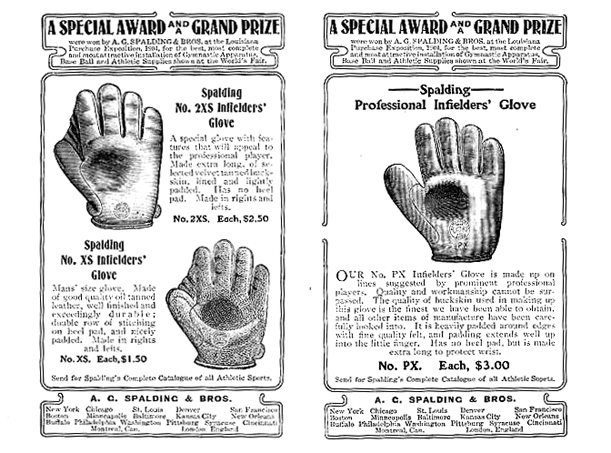

When it comes to the history of the Baseball glove – or “mitt” as it was refereed to in the late 19th century – three iconic sporting goods makers still viable today comes to mind: Spalding, Rawlings and Wilson.

Spalding actually gets credit for the first use of a leather glove in baseball. Not the company, but the man. A.G. Spalding, a pitcher, recognized a need. “I had for a good while felt the need of some sort of hand protection for myself,” Spalding admitted after donning a glove in 1887. “I found that the glove, thin as it was, helped considerably, and inserted one pad after another until a good deal of relief was afforded. If anyone wore a padded glove before this date, I do not know it.”

More players started wearing it and and baseball gloves suddenly were in demand. So Spalding, who is no longer remembered as a player, opened a sports equipment store with the help of his brothers and the A.G. Spalding & Brothers company was born.

In 1887, Rawlings, founded by two brothers George and Alfred Rawlings, followed suit. They also made mitts for baseball among other sporty things, like fishing poles and golf clubs.

Then in 1913, Wilson & Company, a meatpacking plant in Chicago, began using discarded slaughter house byproducts to create strings for tennis rackets, violins and sutures for surgeons. Sensing a surge in popularity, Thomas E. Wilson, the president at the time, bought out an upstart sports manufacturing company named Ashland and began focusing only on the more profitable sport products. In 1916, he renamed the company exclusively after himself.

Making baseball gloves were one thing. Sport helmets were another. For obvious reasons, football players wore head gear as early as the 1920’s. Made only of leather, though, the football helmet protected the ears, but not much else.

Like the leather gloves, Spalding, Rawlings and Wilson were at the forefront of helmet making too. Then in the 1940’s, the War intervened and all three companies were there to help.

Thanks to the design of the football helmet and the leather crafting that dated back to the first baseball gloves, both of the sporting good manufacturing giants were asked to design helmets for the war, specifically tank helmets.

Why tank helmets? That’s because tank radio operators needed to talk to field officers. The steel helmets were good for protection, but they weren’t very useful for communication. So Spalding and Rawlings were recruited to make a leather helmet that either fit inside a steel one or had a hard top attached. It also required these specifications: It had to be equipped with a microphone, earphones, connecting jacks, and protected the crewman’s head from hits on the steel interior.

Military historian and author Adam Makos described the World War II tank helmet this way: “Made of fiber resin, it looked like a cross between a football helmet and a crash helmet, and had goggles on front and headphones sewn in to the leather earplugs.” Makos points out that the first tank helmets were patterned after 1930’s-era football helmets.

Today the World War II tank helmets are rare and collectible and the ones found in good condition like the Rawlings M38 fetch big prices on the auction market.

Several years after the war, in 1950, a new niche and market was created when the National Football League mandated the use of plastic helmets after initially rejecting the idea due to a safety issue (they were considered too hard). Then in 1958, baseball’s American League followed suit by requiring all players don a plastic helmet while batting.

Once again, Rawlings, Spalding and Wilson were there to help.

(Sources: “The Invention of the Baseball Mitt” – Jimmy Stamp, Smithsonian July 2013; Spearhead (book) by Adam Makos; various internet sites)

The ‘Psychic’ Dog That Picked Kentucky Derby Winners

By Ken Zurski

In the 1930’s, as the story goes, the Llewellyn setter known as “Jim the Wonder Dog” correctly picked the winner of seven Kentucky Derby’s in a row.

Yes, that’s seven winners – all in a row.

If true, the predictions are quite impressive considering that between 1930 and 1936, while there were two favorites who won (Gallant Fox ’30 and Twenty Grand ’31), there were also two long shot winners: 1933’s Broker’s Tip went off at 8-1 and Bold Venture in 1936 crossed the finish line first at a whopping 20-1.

Jim the Wonder Dog apparently picked them all.

Here’s how it all went down: Jim’s owner Sam VanArsdale would set down sealed envelopes each containing the name of a horse in the race. Jim would walk up to one and put his paw on it. The envelope was then stored in a safe. After the race, the envelope was reopened revealing the winning horse each time. The soft spoken VanArsdale never wanted to profit off his prized pooch so he turned down all offers to reveal the contents of the envelopes before the race.

According to VanArsdale, Jim’s unusual abilities began at an early age. One day, while out in the field hunting, VanArsdale found that Jim could understand what he was saying to him. “Let’s go over and rest a bit under that hickory tree,” VanArsdale would say and Jim would go to the hickory tree bypassing all the other oaks, walnuts and cedars in the woods. When VanArsdale asked Jim to go to the walnut tree, Jim went directly to the walnut.

What this all meant was confounding. Dogs follow commands all the time and through mostly recognizable sounds. But Jim seemed to understand the sound and the word. Apparently, Jim was able to understand commands in any language including Morse code.

Then his psychic abilities kicked in. Jim was credited with accurately guessing the gender of babies before they were born.

The Kentucky Derby predictions certainly got attention and Jim was asked to pick the winner of the 1936 World Series. Jim choose the New York Yankees to beat the Detroit Tigers (The Yankees were favored and won in six games). After that and thanks to the press coverage, Jim became instantly famous. Even Ripley’s Believe it or Not picked up on his story.

Was it all a hoax as many questioned? Doubters were aplenty, but VanArsdale insisted it was no trick.

“Scientists examined Jim and college classes in psychology observed him without being able to suggest an explanation,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote, in March of 1937, shortly after Jim died at the age of twelve. “VanArsdale as always denied he has no signals and nobody ever caught him at it.”

The papers pointed out that VanArsdale refused all offers to commercialize the dog and go on the vaudeville circuit.

Jim was buried in a special constructed casket near his hometown of Marshall, Missouri. Flowers from all over the country were sent to his graveside and VanArsdale claims to have received 500 letters of condolence. In one last fitting testament to Jim’s psychic abilities, when asked if he thought his dog had a form of mental telepathy, VanArsdale humbly replied that “he did not know.”

In 1999, sixty-two years after his death, a park was built in Marshall near the hotel boarding room Jim shared with VanArsdale.

That same year, a statue of Jim The Wonder Dog was dedicated in the park’s gardens.

(Sources: Various internet sites including jimthewonderdog.org and newspapers.com)

Le Pétomane: France’s Famous ‘Flatulist’

By Ken Zurski

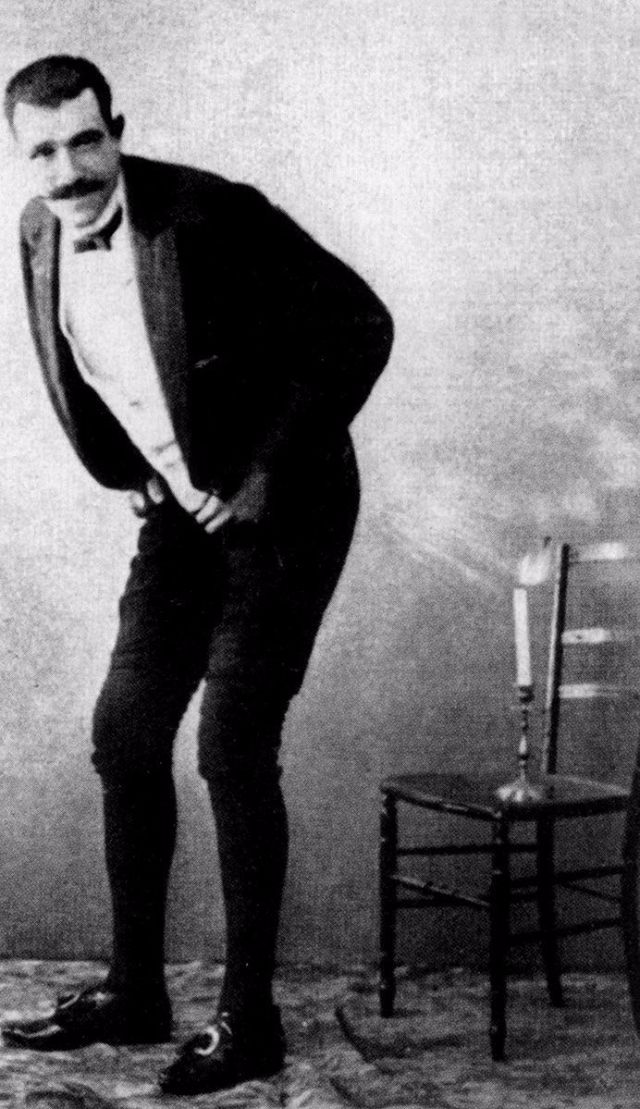

Even at an early age Joseph Pujol knew he had a gift, or curse, he wasn’t sure.

One day while wading in a watering hole, Pujol felt his inside fill with water. Strangely, though, his head was not submerged. Once on shore, the young Pujol was able to expel the water from the same place it entered. Later when asked, he would say matter-of-factly, “I can breathe through my arsehole.”

But not just “breathe,” Pujol could also send air out his backside at an accelerated rate of speed too. Doctors were baffled. But audiences couldn’t get enough. With the stage name Le Pétomane which combined the words “fart” and “maniac,” Pujol delighted late 19th century Parisian crowds with his tricks and sounds.

Many called him “The Fartiste” or “The Flatulist”, a take on the scientific name for accumulating internal gas – or flatulence. The audiences came prepared for a sound and smell experience, but since Pujol sucked outside air in and blew it out just seconds later, there was no offensive odor.

The stage act was as outrageous as it sounds.

Wearing a form fitting tuxedo with tails, Pujol would set up each stunt with a few carefully chosen words and a combination of hand and face gestures. Then with a professional confidence he would bend over and proceed to extinguish a candle from a foot away, just as he told the audience he could.

In other examples of his craft, Pujol smoked a cigarette using a rubber hose and did impressions too. “Now a hen makes a terrible racket,” he would recite in a sing-song voice, “from the sounds that we hear it’s not one but a packet.” Then the sound like a cackling hen would reverberate around the room.

The act’s encore was his take on vocal interpretations. Although no words were spoken, the musical tones coming from Pujol were clearly distinguishable.

His most popular mimic was a screech he called, “The Mother-in-Law.”

(Note: The :30 second film footage above at the Moulin Rogue and made by Thomas Edison was silent. In the world of the internet, there is a version with copycat sounds added).

Lefty Leonardo and the Foretelling Symbolism of ‘The Last Supper’

By Ken Zurski

In Leonardo da Vinci’s 15th century masterpiece, “The Last Supper,” among the artist’s many symbolic intentions was in the portrayal of Judas.

Specifically, Judas’ hand.

In the painting, Judas is seen turning his head away and reaching for the same dish as Jesus; a gesture that was seen as an emblematic sign of a thief. Other depictions also showed this manifestation, but in da Vinci’s work, Judas uses his left hand, rather than the right, to foretell Christ’s fate.

Judas is seated to Jesus’ right so it seems only natural to reach with the closest hand (in the case the left). But as art historians claim, da Vinci may have had more in mind. That’s because at the time being left-handed was seen as a curse; more fearful and suspicious, rather than enduring.

On top of that, da Vinci was also left-handed. Therefore, the speculation in theory at least is credible. Did da Vinci purposely paint Judas reaching with his left hand, signifying perhaps that the man who betrayed Jesus was a “cursed” lefty? As with anything so subjective, especially in regards to an artist intent, only the artist truly knows. So that answer left, as Da Vinci did, nearly five centuries ago.

As for the “curse” claim, however, the history of Christianity seems to back it up. In the church, left-handiness was a sign of bad luck, citing Roman auguries, where a bird or other object sitting on the left side of a priest was an indication of evil things to come.

For centuries, the right hand preference was encouraged or strictly enforced. Men fished and would plough fields with their right hand, lest they burden their families with famine. And a mother teaching her baby to eat would only let the right hand stick out of the child’s swaddled clothing. “If they put forth their left hand,” the early Greek biographer Plutarch (45 A.D.) one wrote, “they were corrected.”

Today an estimated 10-percent of the world’s population is born left-handed and many become noteworthy because of it. Da Vinci in particular certainly endured the backlash. Perhaps he dared to mock his own affliction by portraying Christ’s betrayer as a dreaded “southpaw,” all the while creating it with a brush stroke from his chosen left hand.

When Soap was Taxed and Personal Cleanliness an Option

By Ken Zurski

Beginning in 1712 and continuing for nearly 150 years, the British monarchy used soap to raise revenue, specifically by taxing the luxury item. The tax itself was on the production of soap, not the participation. But due to the high levy’s imposed, the soap makers left the country hoping to find more acceptance and less taxes in the new American colonies.

Cleanliness was not the issue, although it never really was. Soap itself had been around for ages and used for a variety of reasons not necessarily associated with good hygiene. The Gauls, for example, dating back to the 5th Century B.C., made a variation of soap from goat’s tallow and beech ashes. They used it to shiny up their hair, like a pomade.

Even before soap was introduced, rather ingenious ways of cleaning oneself emerged. The Hittites in the 16th century washed their hands with plant ashes dissolved in water. And the Greeks and Romans, who never used soap, would soak in hot baths then beat their bodies with twigs or use an instrument called a strigil, basically a scrapper with a blade, that would scrape away sweat and dirt of the body, similar to what a razor does with hair stubble.

So when actual soap was introduced in the late Middle Ages it had always been considered exclusively for the privileged. Therefore, later when it was mass produced, the British imposed hefty taxes on it as did many other luxury items, like wallpaper, windows and playing cards.

Thank goodness in centuries to follow some common sense emerged.

Or did it.

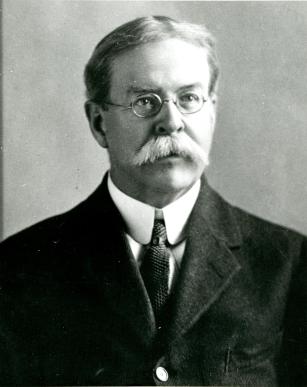

In 1902, psychologist and chemist, William Thomas Sedgwick released a book titled Principles of Sanitary Science and Public Heath which was a compilation of lectures he gave as a professor of biological sciences at MIT.

In it, Sedgwick extolled the virtues of good personal hygiene to keep infectious diseases away. “The absence of dirt,” he urged with conviction, “is not merely an aesthetic adornment.”

Basically, he was telling everyone to take a bath.

It wasn’t that most people didn’t understand the merits of taking a bath, but it was a chore. Water had to be warmed and transported and would chill quickly. Oftentimes families would use the same water in a pecking order that surely forced the last in line to take a much quicker one than the first. When the baths were over the water had to be lugged outside and dumped.

In the later half of the 19th century, as running water became more widespread, bathtubs became less mobile. Most were still bulky, steel cased and rimmed in cherry or oak. Fancy bronzed iron legs held the tub above the floor.

Ads from the time encouraged consumers to think of the tub as something other than just a cleaning vessel. “Why shouldn’t the bathtub be part of the architecture of the house?” the ads asked. After all, if there is going to be such a large object in the home, it might as well be aesthetically pleasing.

Getting people to actually use it, however, that was another matter.

Sedgwick had medical reasons to back up his claims. As an epidemiologist, he studied diseases caused by poor drinking water and inferior sanitation practices. Good scientific research, he implied, should be all the proof needed. But attitudes and decades old habits needed to be amended too. “It follows as a matter of principle,” Sedgwick wrote, “that personal cleanliness is more important than public cleanliness.” He had a point. Largely populated cities were dirty messes, full of billowing black smoke from factories, coal dust, and discarded garbage and waste. Affixing blame for such conditions was more popular than actually doing something about it. Sedgwick focused on self-awareness to make his point. “A clean body is more important than a clean street,” he stressed.”Sanitation alone cannot hope to effect these changes. They must come from scientific hygiene carefully applied throughout long generations.”

People, it seemed, had to literally be frightened into washing up.

Something Sedgwick understood, but fought to change.

“Cleanness,” he wrote in his book, ”was an acquired taste.”

By this time, soap was being widely used, relatively inexpensive, and no longer taxed in Great Britain. William Ewart Gladstone, the Prime Minister at the time, finally put an end to the soap tax in 1853, nearly a century and a half after it was imposed. In doing so, however, he faced a substantial revenue loss. So to make up for this financial scourge he introduced death duties, basically a tax on the widow of a dead spouse.

“This woman by the death of her husband became absolutely penniless,” announced the Common Cause, citing a recurring example.

With that, Gladstone might have argued that using soap might actually help your cause.

An Opening Day Presidential ‘First Ball’ Toss

President Taft Tosses First Ball

Great Opening for American League

All Attendance Records Broken in Washington

Washington, April 14, 1910 — The opening of the American League season in Washington today between the local and Philadelphia clubs, was a most auspicious one. President and Mrs. Taft, Vice president Sherman and many other notables were present and the Nationals won by the shut out score of 3 to 0. For the first time on record, a president of the United States tossed out the first ball and what was more he sat through the entire nine innings and seemed greatly to enjoy the contest. The attendance broke all records.

Last year, President Taft saw Washington play Boston late in the season, but then the local players got stage fright when the President arrived and threw the game. Mr. Taft remarked then that he must be “hoo-doo” and remained away from the ball park the rest of the season. This morning President Noyes of the Washington Club went to the White House and presented to Mr. Taft baseball pass No. 1

Just before play was started Umpire “Billy” Evans made his way to the Taft box on the right wing of the grandstand and handed the President a new ball. Mr. Taft took the ball in his hand as though he was expected to throw it over the plate when he gave the signal. He handed the ball to Mrs. Taft who weighed it carefully in her hand while the President was doffing his gloves in preparation for his debut as a pitcher.

Mr. Taft watched as the players warm up and a few minutes later shook hands with Managers MacAleer and Mack. When the bell rang for the beginning of the game, Mr. Taft shifted uneasily in his seat, the umpire gave the signal and the President raised his arm. Catcher Street stood at the home plate ready to receive the ball, but the President threw it straight to Pitcher Walter Johnson. The throw was low, but the pitcher struck out his long arm and grabbed the ball before it hit the ground. The ball was never put in play as it is to be retained as a souvenir of the occasion.

Hartford Courant Friday April 15, 1910 (Source: Newspapers.com)

President William Howard Taft throwing out a ceremonial pitch. (Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images)

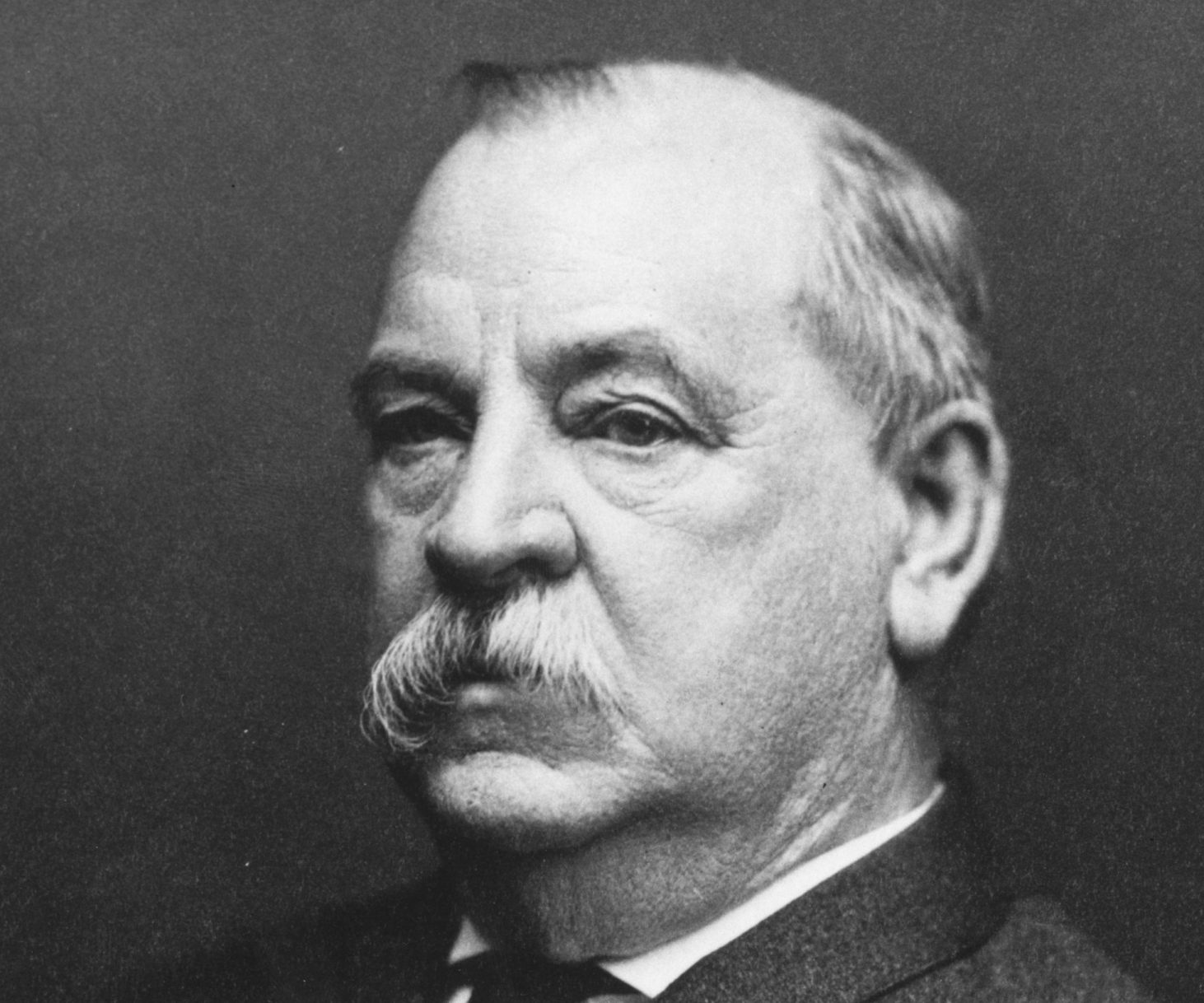

The Only Non-Consecutive Terms President, Grover Cleveland, was Accused of Rape. He Carried it to Victory

By Ken Zurski

In July 1884, only two years after being elected the governor of New York, a little known lawyer and relatively new politician named Stephen Grover Cleveland became the Democratic nominee for president of the United States.

Cleveland’s quick rise in party ranks was no fluke. The Republicans were in disarray. Due to failing health, Chester Arthur the incumbent and former vice president who inherited the White House after James Garfield’s assassination, made only a meager effort to win his parties affections for a full term. Instead Republicans chose James Blaine, a longtime congressman from Maine. The Democrats seized on the opportunity to elect someone who was considered an outsider.

Cleveland fit the bill.

Conservative, religious, and “remarkable unperceptive to new ideas,” Cleveland easily won election to New York state governorship in 1882 and even though he would vote against the public’s favor on issues ranging from reducing fares on New York City’s elevated trains to limiting carriage driver’s work day hours, the public generally liked his “refreshing moral correctness,” so much so he earned the nickname “Grover the good.”

All that would change, however, shortly after Cleveland became the nominee for president.

A Buffalo, New York newspaper, the Evening Telegraph, published a story that put the rotund candidate at the head of a scandal, claiming he had ruined a “respectable” woman’s reputation, seduced her with the promise of marriage, taken away a son that she claimed was Cleveland’s, and dumped her in an insane asylum. Cleveland was a bachelor so there was nothing particularly scurrilous about the relationship with a young woman, especially a widow. But the rest of the accusations, if true, clashed with proper conduct and conventions of a man of Cleveland’s stature. Partisan newspapers throughout the country waved their biased banners; either championing the cause or ignoring and downplaying the reports.

Cleveland’s associates gave an explanation. Without denying the rumors, they claimed a man’s private actions should not be a qualification for political office. A Democratic newspaper, the New York World, run by Joseph Pulitzer, reinforced the claims: “The issue of the campaign is not one of personal character,” the paper reported.

But it got worse. More unsubstantiated reports of women scorned by Cleveland surfaced. It seemed only a matter of time before the Democratic party dropped Cleveland and picked another nominee, a move that would almost certainly tip the general election in the Republicans favor. Cleveland offered another choice. “Tell them the truth” he demanded.

Cleveland never denied knowing the woman named Maria Halpin, but according to him, she was the instigator and ultimately the problem. He was only trying to help a disillusioned woman get her life back together, especially after the birth of an illegitimate child.

Others jumped to Cleveland’s defense. The child in question was not Cleveland’s but Halpin’s other suitor, a businessman named Oscar Folsom. Folsom was also an acquaintance of Cleveland’s. He was also dead. In July of 1875, Folsom was killed in a buggy accident. When the baby was born that September, Cleveland reportedly named the boy Oscar Folsom after his friend.

Halpin wanted more than just help. She wanted a husband and father for a child she was now forced to care for on her own. She claims Cleveland promised to marry her, but didn’t. She also felt betrayed by a man she says took advantage of her. What she wanted now was respect from a man she once trusted. What she got was indifference.

So she cried “rape.”

The rape claim was nothing new to Halpin’s family and close friends, but she kept quiet hoping Cleveland would change his mind. Now, facing misleading reports about her own character, she went public.

Halpin was a 38 -year-old sales clerk at the time working for one of Folsum’s businesses. In her account, Cleveland approached her on the street (actually he had been courting her for some time) and they wined and dined together. Upon returning to her boardinghouse one night, Halpin recalled, Cleveland forced himself upon her. “Violently and without my consent,” she insisted. She remembers Cleveland saying he would ruin her if she ever spoke out. So she asked him to leave and never come back. Six months later, Halpin discovered she was pregnant.

The press mostly ignored her, choosing instead to listen to men like the outspoken preacher Henry Ward Beecher, who defended Cleveland’s honor. Beecher had some womanizing issues of his own to answer to, but Cleveland needed more friends than enemies. He hired an investigator to do some digging and came back with sympathetic results. “He [Cleveland] accepted responsibilities that one man in a thousand has shouldered and acted honorably in the matter,” the report read. Beecher who was still an influential voice, especially among his throng of loyal parishioners, reinstated his support of Cleveland.

Pulitzer’s World went even further by publishing an article which claimed Halpin called Cleveland “a good, plain, honest man,” in an interview. Halpin, the paper reported, disavowed any previous statements against his character. The statement seemed to echo an affidavit drawn up by Cleveland’s lawyers that they wanted Halpin to sign. It read in part: “Shortly after the death of my husband twelve years ago, I removed to Buffalo with my children. Some time after that I met Mr. Cleveland and made his acquaintance which his acquaintance extended over a period of several months. During that time I received from Mr. Cleveland uniform kindness and courtesy. I now have and have always had a high esteem for Mr. Cleveland.”

Halpin under oath said the affidavit’s “statements contained therein are untrue” and refused to sign it. The affidavit also contradicted Halpin’s earlier claims that she would rather “put a bullet trough my heart,” than exonerate Cleveland.

Halpin filed two affidavits of her own, each within days of each other. The first one claimed the circumstances under which her “ruin” was attained, was too “revolting to revel.” The second one, was more forthright. Cleveland, she attested, “accomplished her ruin by the use of force and violence and without my consent.” None of it mattered. Two days after her second affidavit was filed, Grover Cleveland was elected the 22nd President of the United States. “In Gov. Cleveland, in my judgement, we have a leader who is peculiarly fitted to discharge the great trust of his high office and to redeem these pledges to the satisfaction of the American people,” a Cleveland supporter crowed shortly after the results were in.

After Cleveland’s victory, according to author Patrica Miller, “Maria Halpin went down in the history books as a whore.”

The scandal behind her, Halpin went on to marry a tin store owner named Wallace Hunt and died of a prolonged illness at the age of 55. Her only request was that her funeral not be “too public” for fear of “strangers studying her dead face.”

Meanwhile, while in office, Cleveland took a wife. Francis Folsum was a young lady Cleveland had been courting since she was a teenager. Folsum was also the daughter of the late Oscar Folsum, the man Cleveland suspected of fathering Maria Halpin’s son and ultimately the person who posthumously exonerated the president in the public’s eye. Cleveland had guardianship of Francis, Oscar’s daughter from a previous marriage. She called him “Uncle Cleve.”

They were married in the Blue Room of the White House and Francis became the youngest First Lady in history at the age of 21.

(Sources: “Bringing Down the Colonel” by Patricia Miller; Newspaper.com; various interest sites)