History

The Introduction of Mrs. Claus is a Real Tearjerker

By Ken Zurski

“The Christmas Legend” is a short story written in the mid-nineteenth century by a Philadelphia missionary named James Rees. It tells the tale of a destitute American family that receives an unexpected visit from a couple of strangers on Christmas Eve. The constructive narrative sets up a deep exploration of family, loss and forgiveness; a classic Christmas formula. But the story itself is not widely known. In fact it would likely be completely forgotten had it not been for one word- “wife.” Today, it is cited as being the first time Santa Claus was associated with a spouse. It literately introduced the character we know now as Mrs. Claus.

Published in 1849, “The Christmas Legend” was part of a collection of 29 short stories written by Rees and compiled under the title, “Mysteries of City Life, or Stray Leaves from the World’s Book.” Each story is cleverly presented to represent the dissimilarity of many leaf types. For example, the maple leaf, Rees writes, is “golden and rich” and presents a sunnier disposition, while another like the gum tree leaf has a “bloody hue” and “stands fit emblem of the tragic muse.” He likens authors after the “forest trees” which “send forth their leaves unto the world.”

“And by what emblem shall we appear amongst those clustering trees,” Rees explains. “Let us see – Ah! The Ash Tree leaves are like ours, humble and plain to see, but hiding the silver underneath.”

In “The Christmas Legend,” Rees uses the spirit of the holiday to emphasis this point.

Here is the abbreviated story…

A family of four, mother and father, daughter and son, are sitting near the fireplace on Christmas Eve. The two children, especially the daughter, wonders if she should hang the stockings for Kris Kringle to come. But her mother raises doubt. There are more important things in life than earthly possessions, she states: “Poverty keeps from the humble door all the bright things of the earth, except virtue, truth and religion, these are more of heaven and earth, and are the poor man’s friend in time of adversity.”

“I thought that Santa Claus or Kris Kringle loved all those who are good, and haven’t I been good?” the daughter asks confused.

The mother tells her to leave the stocking up. “Customs at least should be observed, and perhaps the young heart may not be disappointed,” she explains.

The father is more introspective. He anguishes over a lost family member, the eldest child, another daughter who apparently ran away with a “dissipated” man seven years before and hasn’t been seen or heard from since.

Then there is a knock at the door.

Two strangers appear out of the night, an elderly couple carrying a bundle with “all their worldly wealth.” They ask how far away they are from the city and the father tells them it is “two miles.”

“Two miles?” the stranger says sadly, “we will not be able to reach it tonight. My dear wife is nearly tired out. We have traveled far today.”

The father invites them in and offers his best bed for them to rest. The strangers inquire if this is their whole family. “No. No,” the father says, “we had one other – a daughter.”

“Dead; Alas we all must die,” the old woman responds.

“Dead to us,” the man answers. “But not to the world. But let us speak of her no more. Here is some bread and cheese, it is all poverty has to offer, and to it you are heartily welcome.”

There is a silent pause, then the sound of cheerful merriment, music and laughter, is heard through the open windows and doors. It’s their rich landlord, the father explains, mocking the poor. The old man interjects. “Ah, sir, human nature is a mystery, this is one of the enigmas, and can only be explained when the secrets of the hearts be known.”

The next morning, Christmas Day, the family awakes to find their small room filled with presents: books and games and toys. “O Father, Kris Kringle has been here,” the little girl says excitedly. “I am so happy.”

Here Rees as the narrator sets up the moral of the story. “There are moments when the doors of memory and the bright sunshine of hope make the future all clear,” he writes. “Sorrow is not eternal; it has its changes, its stops; its antidote; they came in the moment of trial and – Presto! The whole scene of life is venerated in the pleasing colors of fancy.”

And that’s when something totally unexpected occurs. The old couple reappears to the family not as as they came, but as a vibrant young couple. The children recoil from fright, but the parents are curious. “How is this?” the father asks. “Why these disguises —“

“Hush, sir,” the once old man says laughing. “This is Christmas morn and we now appear to you not as Santa Claus and his wife, but as we are, the mere actors of this pleasing farce.”

The couple recognizes the old woman’s new face. It’s their long lost daughter. The girl hugs her mother, but the father is more skeptical, angry and weary of atonement. He lashes out at the girl as she approaches him. “Stand back!”, he shouts, then chastises the man who stands with her as a “paramour.” She begs him to reconsider. “No Father he is my kind and affectionate husband.”

“Ah, husband,” the father replies. He reaches for his daughter. They embrace.

Rees goes on to explain the girl ran away because she was “young and foolish” but loved the man who was forbidden from her home. They left America for England where her new husband became heir to a large estate. She sent letters home, but they were never received. Now she had returned back to her family on Christmas Day. A gift of love and hope. “Can you forgive me?” she asks.

“Say no more, all is forgotten. All is forgiven,” the father tells her.

Even though it is thinly defined, the mention of Santa Claus’s wife in “The Christmas Legend” is widely considered the first ever to appear in print. Two years later in 1851, the name Mrs. Santa Claus would be mentioned again in a story published in the Yale Literary Magazine. History tells the rest.

Today Mrs. Claus is considered a kindly old woman who helps her husband on Christmas Eve, tends to his colds, stitches his clothes, and feeds his “round belly,” usually with homemade cookies and milk.

“There are many interesting facts both historic and fabulous connected with the ceremonies, customs and superstitions of this day [Christmas], which if collected together today would make and curious and interesting book.” Rees explains in the introduction to his tale.

Apparently, he added to that.

The End of the 1970’s was Both a Good and Bad Time for the Music Industry

By Ken Zurski

The end of the 1970’s, specifically the end of 1979, was both a very good and very bad time for music lovers.

First the good. Two albums – both double disc packages – were released only weeks apart from each other that even today are still considered two of the most influential albums of all time. But the end of the decade was also a tragic and sad one for the music industry when a deadly incident at a rock concert both shocked and angered a nation.

The two albums were both indirectly involved in the grief and healing that would follow.

Released in the final months of 1979, and due to their late arrival that year, both albums are widely considered to be successes in the 1980’s instead. (Note: “London Calling” was released in the UK in December 1979; in the US it was released on January 10, 1980). Regardless of which decade they belong, both have a place in rock n roll history and both deserve recognition for being musically experimental and risky too – after all they were double albums, meaning you got double the music in one package.

In retrospect, the timing was perfect. The 70’s was a turbulent decade for music. While hard rock and arena rock gained prominence in the 70’s, the rise of disco was eventually seen as a threat to rock fans, whose mainstay bands like the Rolling Stones dabbled in the genre of dance music (“Miss You”). The decade started with the break up of the Beatles and ended tragically with that unimaginable and deadly concert disaster.

Despite this, the 80’s was looming and rock needed a boost.

It came from the two albums by The Clash and Pink Floyd, respectively.

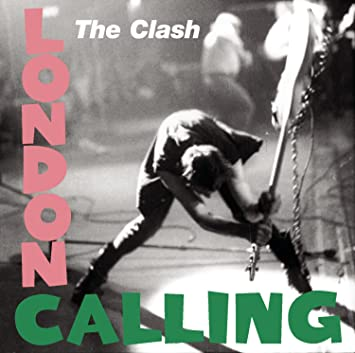

On December 14, 1979, the British group The Clash released their third album titled “London Calling.” The album cover itself was striking. It featured an action shot of bassist Paul Simonon holding a guitar by the neck and ready to smash it to pieces. It captured a moment of pure rock n roll explosiveness. It also conveyed the group’s reputation as rebellious and unflinching.

The album sold as expected, reaching #27 on the US Billboard charts, and doing even better overseas. Critics adored it calling it a “masterpiece” and placing it on Top Ten lists of the year for both 1979 and 1980.

As albums go, before the digital age, it is considered a work of genius, conceptually too. Most double albums seemed overextended and unnecessary. “London Calling” was different. It was a complete work of art, from the music to the package. And that cover? Iconic. And although music itself is always subjective, most rock historians agree, “London Calling’ is a classic in the true sense of the word. Today, it is the 6th most ranked record on critics’ lists of the all-time greatest albums according to Acclaimed Music. The Clash would go on to have bigger selling albums and singles, but for both musicianship and inventiveness, “London Calling’s” legacy is solid.

Before “London Calling” dropped, however, another double album was released. Unlike the Clash’s dramatic action shot on the cover, the front of this album was simple in design: a drawing of a white brick wall. But that was it. There was no writing on the wall, so to speak. If not for a transparent naming sticker attached to the cover, there was no other way of knowing who was responsible until you turned the album around.

The band, of course, was Pink Floyd and the work was appropriately titled, “The Wall.”

Pink Floyd was an established band, known for its conceptual albums and “The Wall,” their 11th release, was no exception. It was however, their first double LP and the reaction to its apparent expansiveness was mixed. “I’m not sure whether it’s brilliant or terrible, but I find it utterly compelling,” was the response from Melody Maker.

Despite the tepid response from critics, the album was a instant best seller, topping the charts in multiple countries, including the US.

Today, it is considered a classic that has stood the test of time. Several songs like “Another Brick in The Wall Part II” and “Comfortably Numb,” are rock radio staples and a movie of the album’s concept about a drugged out rock n roller who figuratively builds a wall around his troubled life, was released in 1982. Recent year tours of “The Wall,” with varying members of the band participating, are huge successes It still has legs, they say in the business.

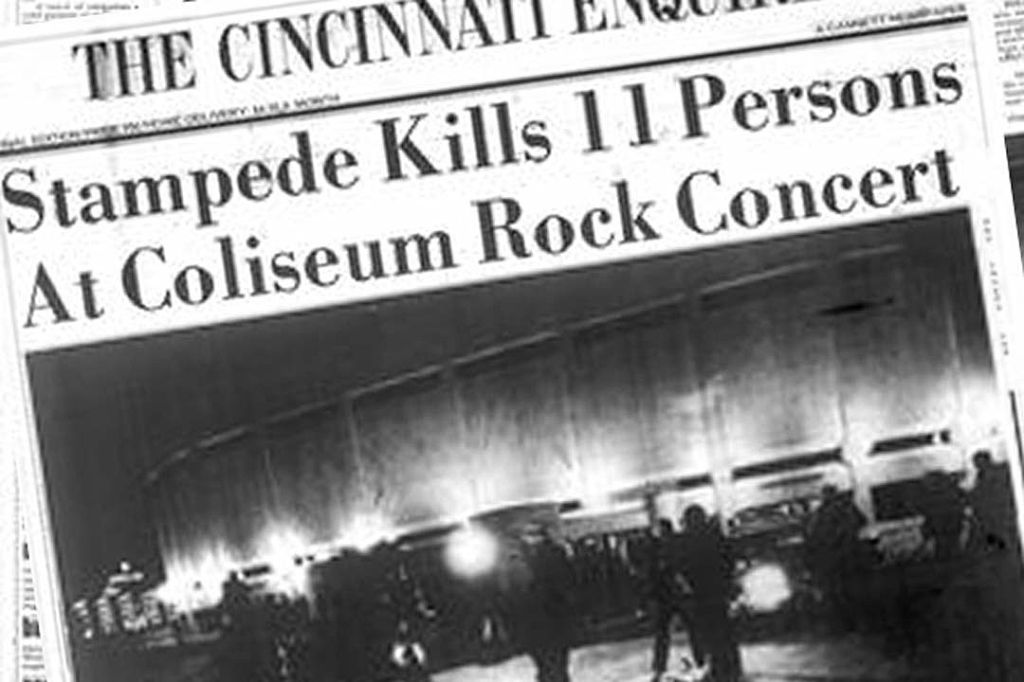

The album’s initial release in late November, however was marred by tragedy when on December 3, 1979, eleven people were killed, crushed to death in a stampede, before a Who concert in Cincinnati. Just days before, in reviews, the comparisons of the dark and satirical “The Wall” to the Who’s classic double album rock opera “Tommy” was justified, but purely coincidental, considering the circumstances.

The Who were not held directly responsible for the deaths of the concertgoers, but it didn’t matter. The industry as a whole took a hit. After the tragedy, the rock world paused to mourn, reflect, regroup, and eventually move on.

Pink Floyd’s “The Wall” was a part of that.

A week later, on December 14, The Clash’s “London Calling” was released.

Bring on the 80’s.

A Christmas Song written by a US Presidential Candidate and Once Covered by Gene Autry is Forever Immortalized in a Cartoon Short

By Ken Zurski

In 1951, cowboy crooner Gene Autry released a song titled “The Three Little Dwarfs,” that playfully told the story of three “helpers” trusted by Santa to “drive” his sleigh on Christmas Eve.

The song was written by Stuart Hamblen, a singer, songwriter and politician who ran for President of the United States in 1952 on the Prohibition Party ticket. “A cowboy singer, former racehorse owner and converted alcoholic,” Time magazine wrote that year about Hamblen who picked up 73,000 votes, second most by a third party candidate.

Before politics, the Texas born Hamblen was known for being one of the first singing cowboys and in the 1930’s hosted a popular radio show called “Family Album.”

Hamblen wrote several hits for country radio but nothing quite as enduring as “The Three Little Dwarfs.”

The most famous singing cowboy, Gene Autry recorded the song and released it as a single with a B side tune titled “32 feet – 8 Little Tails.” In December 1951, Columbia Records ran an ad in Billboard listing the label’s “best sellers.” Autry’s “The Three Little Dwarfs” was listed just ahead of his version of “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer.”

Today, Autry’s version of “Rudolph” is considered a holiday staple, while “The Three Little Dwarfs” is mostly forgotten.

The song itself however is not.

It was immortalized in a two-minute stop-animation cartoon titled “The Three Little Dwarfs,” but more commonly known as “Hardrock , Coco and Joe.”

Oh-lee-o-lay-dee, o-lay-dee-I-ay

Donner and Blitzen, away, away

Oh-lee-o-lay-dee, o-lay-dee-I-oh

I’m Hardrock! I’m Coco! I’m Joe!

The short premiered on Chicago’s WGN-TV on Christmas Eve 1956.

Autry’s song was not the one used in the short. The tune was re-recorded and reworked. For instance, a narrator is used to speak some of words rather than sing them.

But the most recognizable difference was in Joe’s line. In Autry’s rendition, Joe is sung in a high-pitched voice rather than the distinctive and memorable deep bass of “I’m Joe” featured in the animated version.

Share this:

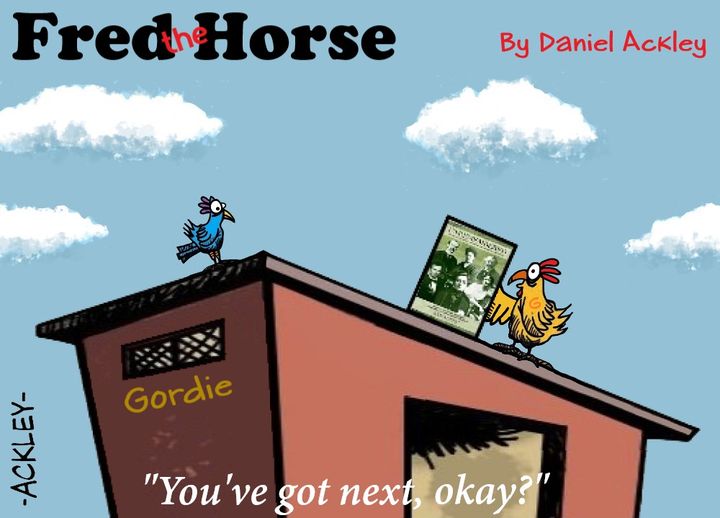

‘UNREMEMBERED Book 2’ Featured in Comic Strip Series

Illustrator Daniel Ackley has featured Ken Zurski’s new book “Unremembered Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers and Influencers” in his comic strip series “Fred the Horse.”

“Fred the Horse” is described as a light-hearted comic strip about the misadventures of Fred The Horse down on the farm in Illinois.

In the strip, somehow Zurski’s book keeps getting into the hands of several characters that inhabits Ackley’s setting for “Fred the Horse.”

Daniel A. Ackley is a Peoria based artist, documentary filmmaker and entrepreneur. His comics appear in various newspaper publications and Peoria Magazine. See more of his work or contact Daniel Ackley at https://ackleytoon.com/ https://www.facebook.com/AckleyArt/

Order the book here: https://www.amikapress.com/books/unremembered-book-2

It’s Time to Salute the Golden Eagle, Not Just the Bald One

By Ken Zurski

It’s hard to imagine anything other than the majestic bald eagle as the symbol of the United States of America, but back in the late 18th century, when good and honorable men were deciding such things, there were several considerations vying for a symbol which best represented the new country.

Benjamin Franklin was one such decider. Although Franklin didn’t quite nominate another bird, the turkey, as some history lessons would suggest, it was the use of the bald eagle as the symbol of America that most infuriated the elder statesman.

“[The bald eagle] is a bird of bad moral character,” Franklin wrote to his daughter. “He does not get his Living honestly.”

For Franklin it was a a matter of principal. The bald eagle was a notorious thief, he implied. Here’s why the perception is a reasonable one at least: Bald eagles are considered good gliders and even better observers. Therefore, they often watch other birds, like the more agile Osprey (appropriately called a fish hawk) dive into water to seize its prey. The bald eagle then assaults the Osprey and forces it to release the catch, grabs the prey in mid-air, and returns to its nest with the stolen goods. “With all this injustice,” Franklin wrote as only he could, “[The bald eagle] is a rank coward.”

Franklin then expounded on the turkey comparison: “For the truth, the turkey is a much more respectable bird…a true original Native of America who would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his farmyard with a red coat on.”

Regardless of his turkey argument, was Franklin’s assessment of the bald eagle as a “coward” a fair one?

Ornithologists today provide a more scientific and sensible explanation. In the”Book of North American Birds” the bald eagle gets its just due, for as a bird, it’s actions are justifiable. “Nature has her own yardstick, and in nature’s eyes the bald eagle is blameless. What we perceive as laziness is actually competence.” Being able to catch a “waterfowl in flight and rabbits on the run,” the book suggests is a noble and rewarded skill.

Perhaps, a better choice for the nation’s top bird, might have been the golden eagle, who unlike the bald eagle captures its own prey, mostly small rodents, but is powerful enough to attack larger animals like deer or antelope on rare occasions. (Its reputation today is tainted somewhat by rumors that it snatches unsuspecting domestic animals, like goats or small dogs.) But golden eagles don’t want attention. They shy away from more populated areas and appear to be “lazy” only because they can hunt with such precision and ease they don’t really have to ruffle their feathers.

The reason why America chose the bald eagle over the golden eagle to be the nations symbol, however, seems obvious by default. History had already pinned the golden eagle as a symbol of warrior strength and victory (“perched on banners of leading armies, the fists of emperors and figuring in religious cultures)” among other heroic and stately attributes. Basically, the golden eagle had been taken.

The bald eagle, by comparison, would be truly American.

Perhaps when Franklin made the disparaging comments against the bald eagle he was also harboring a nearly decade old grudge.

In 1775, a year before America’s independence, Franklin wrote the Pennsylvania Journal and suggested an animal be used as a symbol of a new country, one that had the “temper and conduct of America,” he explained. He had something in mind. “She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders;” he wrote. “She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage”

Franklin’s choice: the rattlesnake.

Teddy’s ‘Immensely Pleasing’ Feisty Blue Macaw

By Ken Zurski

Theodore Roosevelt was known to capitalize the word “nature,” so it’s no surprise that when the 26th president took over the White House he brought with him a virtual zoo.

The Roosevelt sanctuary included a small bear named Jonathon, a pig named Maude, a lizard named Bill, several guinea pigs, a badger, a “one-legged” rooster, a barn owl, a hen, a hyena, a calico pony, and a blue macaw named Eli Yale, who flew in the White House conservatory, but often flew in the halls too.

(The origin of the bird’s name comes from Eilhu Yale, an 18th Century British Merchant, and the the namesake of Yale University. “Eli” is an informal name given to Yale graduates. Teddy was a Harvard man but admired the Yale School of Forestry, an institution founded by friend and fellow conversationalist Gifford Pinchot, a 1889 Yale grad).

Teddy was especially fond of Eli because it had a reputation of being noisy and ornery to the staff. This pleased the president immensely. “Eli has a bill that could bite through a boiler plate,” the president delightfully warned.

In 1902, when the White House conservatory was being repaired, Eli was said to be in a rage. “The President’s bird has not hesitated to use some choicest terms on [the workers] whenever they encroached upon her premises,” the papers reported.

In 1909, when Roosevelt and the animals left the White House, the conservatory would soon be gone too. That same year, President William Howard Taft tore it down to extend the West Wing.

The current Oval office resides there today.

Wash Your Hands? In the 19th Century it was ‘Please Take a Bath’

By Ken Zurski

In 1902, psychologist and chemist, William Thomas Sedgwick released a book titled Principles of Sanitary Science and Public Heath which was a compilation of lectures he gave as a professor of biological sciences at MIT. In it, Sedgwick extolled the virtues of good personal hygiene to keep infectious diseases away. “The absence of dirt,” he urged, “is not merely an aesthetic adornment.”

Basically, he was telling everyone to clean up. In essence, please take a bath.

Sedgwick was onto something. Until then taking a bath, for example, was an option most people chose to ignore. That’s because for centuries, cleanliness was seen as a sign of weakness or impurity. In some ancient religious philosophy’s, being wet, or letting the water touch you, was akin to allowing the devil enter your body. And in other circles, bathing was considered a sign of sexual mischievousness. Queen Isabella of Castile bragged that she took a bath only twice in her life, on her birth day and her wedding night. And Saint Benedict, an English monk who lived a solitary and monastic life, said “bathing shall seldom be permitted.”

Of course that was a long time ago when attitudes were based on god fearing principles, not logic. But even at the turn of the 20th century, personal hygiene was still somewhat taboo.

Sedgwick though wasn’t the first to encourage others to get well by getting clean. Benjamin Franklin, a man of many titles, was also an early advocate of good hygiene habits.

As America’s first diplomat in France, Franklin thoroughly enjoyed the pleasures of taking a bath, a European luxury, although his desires may have been influenced more by the pretty French maids who administered it. “I have never remembered to have seen my grandfather in better health,” William Temple Franklin wrote to a relative. “The warm bath three times a week have made quite a young man out of him [Franklin was in his 70’s at the time]. His pleasing gaiety makes everybody love him, especially the ladies, who permit him always to kiss him.” Regardless of his reasons for actually taking a bath, Franklin couldn’t help but get clean, right?

However, when a large tub of warm water wasn’t present, Franklin liked to take what he called “air baths.” Franklin thought being inside and cooped up in a germ infested, walled, and shuttered space, was the reason he got colds. So to keep from getting sick, Franklin would open the windows and stand completely naked in front of it. Ventilation was the key to prevention, he explained, although others likely weren’t so emboldened.

In the mid 19th century, bathtubs were heavy and costly and those who could afford it used it as much for decoration as for its intended purpose.

Before indoor plumbing, a large tub may have been made of sheet lead and anchored in a box the size of a coffin. Later bathtubs became more portable. Some were made of canvas and folded; others were hidden away and pulled down like a Murphy Bed. They were called “bath saucers.”

It wasn’t that most people didn’t understand the merits of taking a bath. It was just a chore to do so. Water had to be warmed and transported and would chill quickly; then dumped. Oftentimes families would use the same bath water in a pecking order that surely forced the last in line to take a much quicker dip than the first.

In the later half of the 19th century, as running water became more common, bathtubs became less mobile. Most were still bulky, steel cased and rimmed in cherry or oak, but stationary. Fancy bronzed iron legs held the tub above the floor.

Ads from the time encouraged consumers to think of the tub as something other than just a cleaning vessel. “Why shouldn’t the bathtub be part of the architecture of the house?” the ads asked. After all, if there is going to be such a large object in the home, it might as well be aesthetically pleasing.

Getting people to actually use it, however, that was another matter.

Sedgwick had medical reasons to back up his claims. As an epidemiologist, he studied diseases caused by poor drinking water and inferior sanitation practices. Good scientific research, he implied, should be all the proof needed. But attitudes and decades old habits needed to change too. “It follows as a matter of principle,” Sedgwick wrote, “that personal cleanliness is more important than public cleanliness.” He had a point. Largely populated cities were dirty messes, full of billowing black smoke from factories, coal dust, and discarded garbage and waste. Affixing blame for such conditions was more popular than actually doing something about it. Sedgwick focused on self-awareness to make his point. “A clean body is more important than a clean street,” he stressed.”Sanitation alone cannot hope to effect these changes. They must come from scientific hygiene carefully applied throughout long generations.”

People, it seemed, had to literally be scared into taking a bath.

Something Sedgwick understood, but fought to amend.

“Cleanness,” he wrote in concession, ”was an acquired taste.”

In March 1868, Three Years After the War, Mary Logan (the General’s Wife) Visited Richmond…

By Ken Zurski

General John A. Logan could not go.

“Blackjack Logan” as his men affectionately dubbed him due to his strikingly dark hair and eyes, was invited by a newspaper man in Chicago, Charles Wilson, to visit Richmond, Virginia.

It was March 1868, and Logan now the leader of the Grand Army of the Republic was too busy in the nation’s capital overseeing veteran’s affairs to break away. But Wilson had invited the entire Logan family with him on the trip. So he insisted Logan’s wife Mary, daughter Dolly and baby son, John Jr. still attend

The general gave them his blessing.

In Richmond, Mary Logan was prepared for the worse. Large portions of the city had been destroyed by fire and now three years removed from the brutality of war, it still resembled a battleground. “Driving from place to place we were greatly interested and realized more than we ever could have, had we not visited the city immediately after the war, the horrors through which the people of the Confederacy had passed,” Mary recalled after arriving.

Because of its proximity to Washington, many Union leaders, including President Lincoln, toured Richmond shortly after the North captured the embattled Southern capital. Lincoln arrived with his son Tad on April 4, 1865 to a military-style artillery gun salute. He viewed first hand the devastation caused by the fires set by the escaping Rebels. The city’s structures were nearly gone, but the war was over. Five days later, General Robert E Lee signed surrender papers. Less than a week after that, Lincoln was dead.

But Richmond survived.

“The hotel we stayed in was in a very wretched condition,” Mary would later write about her trip. “And we expected to find the rebellion everywhere.” Wilson, another war veteran, was interested in seeing Libby prison, so they took a carriage to the site. Along the roads, Mary noticed people still picking up the remnants of exploded shrapnel, broken cannon and Minie balls to sell for iron scrap at local foundries. She remembers passing a poor little boy, so “thinly clad that he had little to protect him for the inclemency of the weather.” The March chill had given the city a depressing glumness.

“Well isn’t it so miserably hot to-day,” Mary recalls the boy humorously calling out to the driver, while at the same time, “his teeth were chattering,” she wrote.

The carriage then made its way to the cemeteries.

This is where Mary took pause. Not only were there endless lines of stones, but they were all decorated. Mary was moved by the site. “In the churchyard we saw hundreds of graves of Confederate soldiers. These graves had upon them bleached Confederate flags and faded flowers and wreaths that had been laid upon by loving hands.” Mary stopped to reflect. “I had never been so touched by what I had seen,” she said.

When she returned to Washington, Mary summoned her husband and told him what she had witnessed at the grave sites. General Logan said that it was a beautiful revival of a custom of the ancients preserving the memory of the dead. “Within my power,” he promised her, “I will see that the tradition is carried out for Union soldier as well.” A promise he did not wait long to keep.

Almost immediately, Logan sent a letter to the adjunct- general of the Grand Army of the Republic, dictating an order for the first decoration of the graves of Union soldiers. He wrote:

The 30th day of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance no form or ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit.

On May 30, just as Logan had ordered, the first Decoration Day, now more commonly known as Memorial Day, took place at Arlington Cemetery.

‘Anyone Hear a Plane Crash?’ Flying the Air Mail Over Illinois was Lucky Lindy’s Most Dangerous Job

By Ken Zurski

Shortly before Charles Lindbergh became the most famous person in the world, he flew U.S. Air Mail flights over Illinois in a route from St Louis to Chicago.

At the time, the air mail pilot was considered “the most dangerous job in the country” due to the plane’s limitations and unpredictable weather. Instrument flying was not yet perfected and oftentimes the pilots would fly into situations where the only recourse was to ditch the plane.

This happened to Lindbergh several times, including one night over Peoria…

Charles Lindbergh was falling head first when he pulled tightly on the rip cord and hoped for the best. Suddenly the risers whipped around with a jerk and the free falling weight at the bottom of the harness snapped back into an upright position. The chute was open. But a more precarious threat lay just below. Lindbergh placed the rip cord in his pocket and took out a flashlight. He pointed it downward. “The first indication that I was near ground was a gradual darkening of the space below,” he recalled.

Time was running out.

Just minutes before, in desperation, Lindbergh was flying in circles over Peoria, Illinois looking for a place to land. It was around 8 p.m. on November 3, 1926. A fueling mistake in St. Louis had drained the main tank of the refurbished Army DeHavilland sooner than expected and the reserve tank was just about tapped. An early November snow was falling and visibility of ground lights was less than a half-mile. The Peoria airstrip was only faintly visible. “Twice I could see lights on the ground and descended to less than 200 feet before they disappeared from view.”

With only minutes left in the reserve, Lindbergh steered the craft east hoping to find a clearing in the weather, but it was too late. At least he had made it to a less populated area. “I decided to leave the ship rather than land blindly.” So he jumped.

The snow had turned to a light rain and the water-logged chute began to spin. It was too foggy to see but he could sense it. The ground was closing in. Then the chute stopped spinning just long enough to slow the descent. “I landed directly on a barbed wire fence without seeing it,” Lindbergh remembers.

Expecting the worst, he opened his eyes surprised to be unharmed. The fence helped break the fall and the thick khaki aviation suit kept the barbs from penetrating the skin. There wasn’t a scratch. Lindbergh took his bundled parachute in hand and headed towards the nearest light. He found a road and followed it to a small town. From there he would try to determine where his plane ended up.

B.K. (Pete) Thompson, a farmer, had just entered the town’s general store and was sitting down to a friendly game of cards when a “tall, slim man” walked in.

“Anyone hear a plane crash?” the stranger asked. Thompson offered to help.

Together the two men, similar in age (early 20’s), climbed into the farmer’s Model T to search the country roads. “I’m an airmail pilot,” the stranger told Thompson and introduced himself. Thompson told Lindbergh he was in Covell, Illinois, about seven miles west of Bloomington. “I ran out a fuel over Peoria,” Lindbergh explained.

The search for wreckage was fruitless; it was too dark. “Can you give me a ride to the train station?” Lindbergh asked. The plan was to take a train to Chicago and a fly a new plane over the area in the morning. The ten-mile drive on the dark bumpy roads was treacherous and Lindbergh buckled down for the ride. “For a man who had just ditched an airplane,” Thompson recalled. “He sure held on for dear life.”

If you find the wreckage, Lindbergh explained, there is a 38-caliber revolver in the cockpit. “Guard the mail,” he told Thompson.

Thompson found the wreckage the next day less than 500 feet south of his house. The plane’s main landing gear had torn off at impact. The wings were completely gone but the metal frame of the fuselage and tail were still intact. One wheel had broken loose and covered a full hundred yards before crashing through a fence and resting – fully inflated – against the wall of a hog house.

The revolver was still there; right where Lindbergh had said it would be. And three large U.S. Air Mail bags were on board too – one was split open and slightly oiled, but still legible.

Around mid-morning, the whir of an engine was heard overhead. It was Lindbergh. He landed the reserve plane in a field next to the wreckage and was treated to a fried chicken lunch “with all the trimmings” before loading up the airmail bags and heading back to Chicago to complete his route – some 24 hours late. But even the return trip was hampered by delays. “We spent about two hours trying to get the new plane started,” Thompson recalls. “Lindbergh and I keep pulling the propeller, but it must have been too cold.” Lindbergh had an idea. He went to the farmhouse and boiled 20 gallons of water to heat the radiator.

“The engine kicked right over,” Thompson said.

Thompson never saw the slim man again face-to-face, but would read about his heroics in the paper the following year. That’s when he remembered what the young pilot had told him on the automobile trip to the train station that night. An idea Lindbergh had considered just months before on another mail run over Peoria. While flying placidly through the clouds, Lindbergh mused over the question of balancing weight, fuel and distance and found an answer. “It can be done and I’m thinking of trying it,” he said.

Of course he was talking about crossing the Atlantic.

(Sources: Charles Lindbergh. “Spirit of St Louis” & “We;” A. Scott Berg. “Lindbergh;” Marion McClure. “Bloomington, Illinois Aviation- 1920, 1930, 1940.”)

‘Tobor the Great’ Was a Man-made Mechanical Movie Star

By Ken Zurski

In The fall of 1954, a new movie titled “Tobor the Great” was released in theaters. It was billed as “a science fiction film for kids” and Tobor “a man-made monster filled with every human emotion.”

In the film, Tobor is a fabricated astronaut who can “live where no human can breathe.” He is befriended by 11-year-old Brian, nicknamed “Gadge,” who together battle Soviet agents who want Tobor for themselves.

“Gadge” is taken hostage, but using his emotions, summons Tobor who arrives to save the day by carrying the boy to safety in his clunky arms.

The movie had no name actors and was shot in less than a month. Still kids adored the mechanical Tobor and parents appreciated the heartwarming ending. Critics were mostly kind, evoking a child’s sensibilities in their approval: “To say children will be delighted by this brand new science fiction adventure would be putting it ‘Super Sonic,’” as one reviewer put it.

In Florida at Miami’s Embassy Theater the movie played as a double-bill with another kids film, “Roogie’s Bump,” about a boy’s love for baseball and a heavenly visit from a deceased ballplayer.

“Tobor is filled with lots of scientific chatter in its early reels,” wrote the Miami Herald, “but builds up to a faster pace as the robot comes to the rescue in the final reels.”

The kids featured in the movies are so smart and well-behaved that the Herald reviewer joked: “Patrons of the Embassy can hardly be held accountable if they view the double-bill and go home and beat their normal, average children.”

Today “Tobor the Great” is considered low budget and schlocky and filled with “terrible acting and dialogue.” A contemporary audience on RottenTomatoes.com rates it at 50-percent on the Tomatometer. “This is one of those movies which makes robots seem less scary and more like friends,” goes one positive audience reviewer. Another called it “corny” and “bland.”

None of that mattered to kids in 1954. For months after the movie’s release, Tobor giants were seen throughout larger cities making appearances and holding children aloft just like in a movie.

Tobor toys filled the shelves, including a popular remote-controlled model.

Perhaps the acceptance of the film was due in part to its ingenious title.

The fun was in Tobor’s distinctive name.

Spell it backwards and you discover that Tobor is no “monster,” as the ads suggest, but a simple robot – and a gentle one at that.