Uncategorized

Robert Crowe: The Lawyer Behind Chicago’s Infamous Trials

By Ken Zurski

Robert Emmitt Crowe was born in Peoria, Illinois on January 22, 1879, the last of eight children to Patrick and Annie Crowe, Irish immigrants who came to America in the mid-1800s. The large Crowe clan would only know Peoria for a short time. Before he was of school age, his father, a gas lamp lighter for the city, moved the family to Chicago, where Robert would begin a career in law.

Soon Robert Crowe would become the city’s top prosecutor, known today for a classic showdown with famed Chicago defense attorney Clarence Darrow.

There are no books written specifically about Robert Crowe, but there are plenty about Darrow. The authors of these books do not diminish Crowe’s role as Darrow’s antagonist, nor his short upbringing in Peoria—which, as it turns out, was a tumultuous one for the Crowe family.

The Investigative Imagination

During the Irish potato famine of the 1840s, Patrick Crowe emigrated to the U.S., as did many others from the County Galway region. Crowe carried a grudge against the British government and soon joined a group of Irish nationalists known as the Fenian Brotherhood, whose goal was to free Ireland from British rule.

Bombs went off in London and other key British cities. Then on May 6, 1882, a British royal named Lord Frederick Cavendish and his under-secretary were ambushed and gunned down in a Dublin park. The assassination was tied to radical Irish groups both in Europe and abroad. Soon, the investigation reached America.

Fenian chapters were active in cities like Peoria, where Crowe was a member. Shortly after the British bombings, a zealous group of reporters saw Crowe carrying a tin can on his rounds lighting the lamps. “Suppose that can in his hand was really a bomb to be thrown at the King of England?” they speculated. They became convinced (possibly influenced by alcohol, as one report goes) that Crowe was behind the bombings—and possibly the assassination, too. As the Peoriana notebook put it years later: “The imagination of the news hounds began working.”

A wire story was sent out, and Crowe became international news. “Dynamite Crowe” became his moniker in the headlines. Even detectives from Scotland Yard arrived in Peoria to follow his every move.

Crowe never shied away from his hatred of British policies and even fueled speculation by bragging about Fenian-financed, dynamite-making factories in Peoria and New York. In the end, his reported arrest in Peoria by the U.S. Marshall was fabricated, and the “hoax,” as it would be called, dropped out of the news. But it’s the reason Patrick Crowe left Peoria.

A Crime in Chicago

To the Clan na Gael—the Irish activist group which replaced the Fenian Brotherhood—Crowe was a hero, and they invited him to Chicago. The family moved from Peoria to Chicago’s 19th Ward, a poor neighborhood made up of mostly Irish immigrants.

Robert was only three at the time. He attended Chicago public schools, graduated high school and studied law at Yale University. In 1903, he returned to Chicago and opened a private practice, and his political aspirations eventually led to an appointment on the bench as a criminal court judge.

Described as “jut jawed and thin-lipped, with a steady gaze and intimidating manner,” Crowe was elected Cook County state’s attorney in 1920. Fighting corruption, even in government, was the key to his victory. “The real reason for his failure,” Crowe said of his opponent that year, “is that he is guilty and knows it.”

Crowe is best remembered as the prosecutor in the May 1924 murder trial of 14-year-old Bobby Franks. Two University of Chicago students named Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb—both 19 and from wealthy families—were arrested and charged with the crime. They confessed to abducting Franks, killing the boy and dumping the body in a forest preserve. Clarence Darrow, who had a reputation for defending the defenseless, was hired to take on the case. “It never occurred to me that I would refuse to defend anyone,” he once said.

By admitting they had killed Franks “for the thrill of it,” Leopold and Loeb were guilty… but of what punishment? The city was captivated by the senseless murder and subsequent trial. For a full month, they followed every word.

Crowe, who had a reputation for being tough on crime, pushed for the death penalty, but Darrow pushed back. He believed capital punishment did nothing to prevent crimes like these. Impulse, not fear, Darrow argued, guided violent tendencies. But a frustrated Crowe would have none of it. “The only useful thing that remains for them now is to go out of this life and to go out of it as quickly as possible,” he demanded.

Darrow would win the argument. Leopold and Loeb’s lives were spared, and both received life imprisonment sentences instead.

Crowe was left to ponder whether the outcome was “a repudiation of his hang ‘em high brand of justice,” as one author put it.

The Legacy of Kodak’s Autographic Camera

By Ken Zurski

In 1914, Eastman Kodak Company introduced a new line of cameras that not only took a picture but recorded the date and title as well. Actually, the date and title was up to the picture taker to record, but nonetheless as Kodak advertised, “any negative worth the making is worth the date and title.”

Kodak called it an “autographic camera” and here’s how it worked: A special film was used that contained a small piece of tissue carbon between the film and the paper backing. A little window on the back of the camera would be opened and with a metal stylus the text could be written on the carbon. The window was left open briefly for exposure and when the pictures were developed, the notation would be visible between the prints. “These notations add to the value of every picture you make,” Kodak insisted.

Jacque Gaisman, a French-American who invented the safety razor, is credited with the concept. He sold it to George Eastman for $300,000. Eastman had high hopes for the new technology, but it never caught on.

Still, it has its place in history. In 1924, British mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine were lost and presumed dead on Mount Everest during Mallory’s fourth attempt to become the first person to reach the elusive summit. Mallory had brought a photographer along, a man named John Noel who used a motion picture camera that weighed 40 pounds.

Mallory, however carried a smaller Kodak vest camera which had the autographic feature. The camera was believed to be on Mallory when he and Irvine vanished.

In 1999, an American climbing team tracing Mallory’s steps discovered the famous climber’s frozen corpse. They were hoping to find the camera too. Perhaps it could tell the tale of Mallory’s last days.

But the camera was missing.

Speculation is Mallory gave it to Irvine to take pictures of him reaching the summit before perishing on the Northeast edge. But no one knows. In 2024, A Chinese documentary team found a boot, with remains, believed to be Irvine’s foot, but no camera was found.

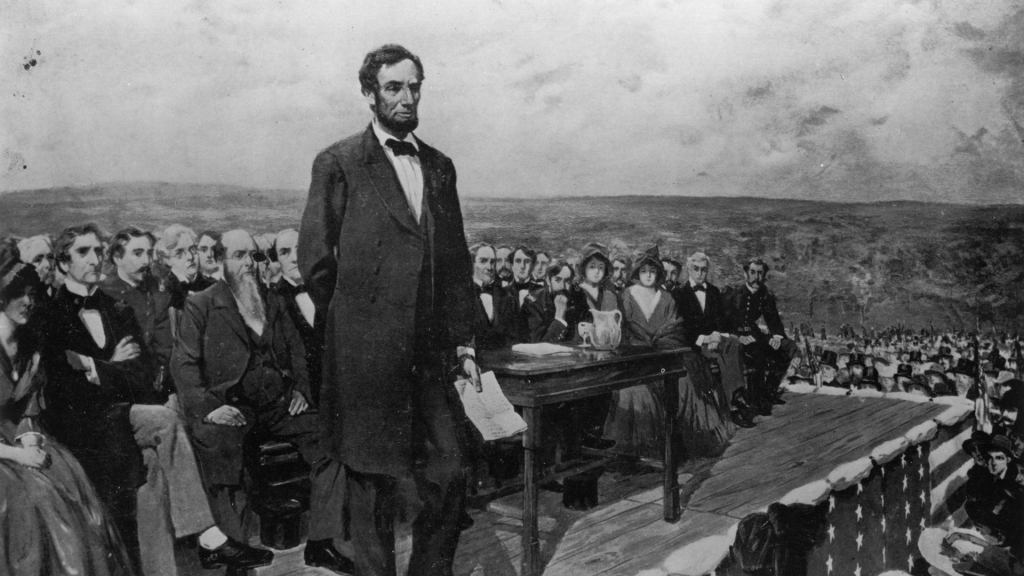

13,000 Words. The Gettysburg Speech before Lincoln’s Address

“Senator Edward Everett had spent his life preparing for this moment,” wrote historian Ted Widmar in “The Other Gettysburg Address.” “If anyone could put the battle into a broad historical context, it was he. His immense erudition and his reputation as a speaker set expectations very high for the address to come.”

Indeed, as Widmar implied, Everett knew the moment was an important one for the country. He was on the battlefield of Gettysburg, now a makeshift graveyard, soon to be the nation’s first national cemetery.

It was November 19, 1863.

He began: “Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature. But the duty to which you have called me must be performed;–grant me, I pray you, your indulgence and your sympathy.

Two hours and 13,000 words later he was done: “I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country there will be no brighter page than that which relates the battles of Gettysburg.”

Widmar wrote: “As it turned out, Americans were correct to assume that history would forever remember the words spoken on that day. But they were not to be his. As we all know, another speaker stole the limelight, and what we now call the Gettysburg Address was close to the opposite of what Everett prepared.

Lincoln spoke: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal….”

When Lincoln ended, it was hardly an address. “Simply the musings of a speaker with no command of Greek history, no polish on the stage, and barely a speech at all – a mere exhalation of around 270 words,” Widmar explained.

It was over in just two minutes.

“Everett’s first sentence, just clearing his throat, was 19 percent of that – 52 words,” Widmar remarked.

The next day , Everett sent Lincoln a note: “Permit me also to express my great admiration of the thoughts expressed by you, with such eloquent simplicity & appropriateness, at the consecration of the Cemetery. I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” he wrote.

All Hail Coffee Soup! Wait…What?

By Ken Zurski

The Amish culture goes back to Old German Anabaptist roots in the 16th century and is defined today by the simple and private lifestyle of those who follow it. The horse-and-buggy transportation is the most recognizable of the Amish culture followed by the modest and similar clothing that includes a vest and hat for men and a plain three-piece dress, cape, apron and bonnet for women.

As for cooking, a variation of grains, dairy and meats are usually on the menu and water mostly to drink, with milk, coffee and tea too. Coffee can be served in the evening with – or as – a good dessert.

So what’s up with one dish, now specifically identified as Amish influenced, and named coffee soup?

That’s right…coffee with the word soup.

The Amish had a stable lifestyle but also struggled some during the Great Depression. So less was more and soups were at least a meal. You can make a lot of it and even save it for several meals across several days.

Thus was born coffee soup. Or so it seems.

There are few ingredients in coffee soup that start with a brewed coffee base, preferably a dark roast. Then add sugar and cream. For substance, a piece a grain bread cut in pieces or put in whole is added. Each spoonful then gets a chunk of bread and the taste of sweet coffee. It’s served cold, mostly. In more recent times, saltines can replace the bread and in some instances cheese is added.

Of course spices, like cinnamon or something more savory, might be added too, but it’s origins with just three to four simple ingredients are at it’s core.

Ready to try it.

Coffee soup.

Guten Appetit!

(Photo courtesy of Amish365.com)

The Eccentric Speech That Forecasted the Great Chicago Fire

By Ken Zurski

On October 7, 1871, George Francis Train a businessman and self-proclaimed inventor, spoke in front of a large audience at a lecture hall in Chicago.

Train had just returned from traveling around the world in 80 days (later claiming to be the inspiration for Jules Verne’s fictional character Phileas Fogg) and was on a speaking tour to support a run for President of the United States or as he called it “Dictator of the USA.”

But in Chicago, he delivered a stunning speech. “This is the last public address that will be delivered within these walls.” He told the crowd. “A terrible calamity is impending over the City of Chicago.”

Train’s reputation as an eccentric preceded him. While alarming, his prophesying was quickly forgotten. The next day however, a fire broke out that devastated the city.

The Chicago Times was first to report Train’s speech claiming he was part of a fringe group based in Paris, with off-shoot chapters throughout the world, including Chicago. The article asserted the group, Societe Internationale, could not accomplish what they desired – labor unity- by peaceful means and that the “burning of Chicago” was suggested. The other newspaper in town, the Chicago Evening Journal, debunked such claims and blasted the Times for concocting a communist plot against the city.

Train, however, had some explaining to do. He did by claiming his doomsday prediction was actually in response to shifty government policies that left a crowded, neglected city and its infrastructure prone to a disaster – either by flood or fire. The timing, he said, was purely coincidental.

As for the cause of the blaze, the papers soon found another scapegoat – and a sensationalist story to boot – in a diary cow, a lantern and the unsuspecting wife of a saloon owner named Patrick O’Leary.

Historically – and Tragically – April 15 is More Than Just Tax Day

By Ken Zurski

Tax Day, April 15, used to be a big deal.

That’s because years before the internet and e-filing made doing your taxes more convenient, those who owed taxes ostensibly waited until the end of the last day to file their returns.

For some it was symbolic, even if you were due a refund.

So local post offices prepared for the onslaught.

In larger cities smiling postal employees set up a drive through service to allow the so-called “procrastinators” to pull up and simply drop off their returns without even getting out of their vehicles.

But today, because it’s easier to file returns online, the absurdity of dropping tax returns off at the last minute seems pointless. So the colloquial term Tax Day, or April 15, just doesn’t have the same impact as it did years ago.

But historically, the date of April 15 is known for two tragic events.

More recently, in 2013, the Boston Marathon bombing occurred on April 15. The other is from 1912, ironically a year before there was a federal income tax. In that year, on that fateful April day, an ocean liner, the largest of its kind for the day, sank after striking an iceberg in the Atlantic Ocean. “A Night to Remember” as author Walter Lord famously put it is his book about the tragedy.

Yes, the sinking of the Titanic was on April 15.

Additionally, President Abraham Lincoln officially died on April 15, 1865 a day after being shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater.

Understandably, because of its significance for all Americans, April 15, is more associated with taxes, than tragedy. But even the date itself isn’t always ceremonially the last day to file taxes. If the 15th day of April is on a weekend, then the following Monday and Tuesday, either the 16th or 17th, is designated as the national day of filing. And today, if you don’t get your taxes in by the deadline date, just go online and file an automatic extension. Anybody can do it.

So much for a designated Tax Day.

Maybe it’s time to give April 15, the date, back to history:

Remember the Titanic!

Boston Strong!

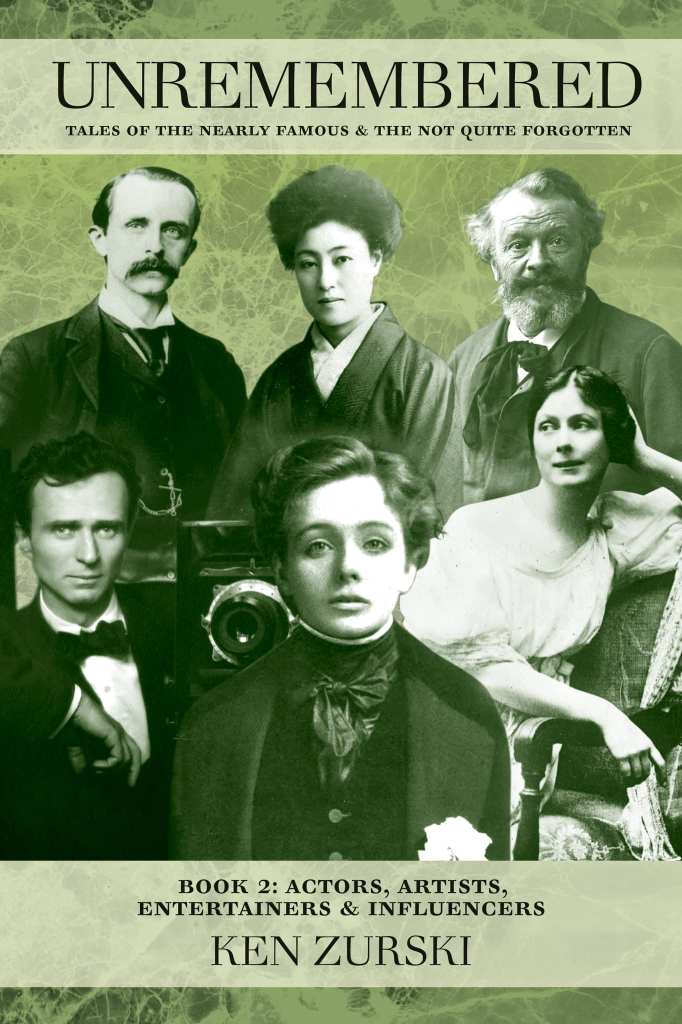

Courier Newspapers Feature Ken Zurski’s Latest ‘Unremembered’ Book

Local author Ken Zurski releases ‘UNREMEMBERED’ sequel

By Madelyn Norman from Courier newspapers

Ellen Terry. Charles Klein. Gaby Deslys. These are names you probably haven’t heard, with stories you won’t forget. In Ken Zurski’s latest “UNREMEMBERED Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers & Influencers,” he shares the history of souls that made all the difference, but go rather unnoticed.

In his sequel, published in September, Zurski shares the attempts and accomplishments of people in the entertainment industry between the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The “UNREMEMBERED” series first began as a blog, unrememberedhistory.com, which now has over 200 stories of forgotten people throughout history. Zurski realized he was able to intertwine these stories in the form of a nonfiction book, utilizing records of the past.

“I wanted to find a story where I could connect things together,” he said. “We have history to tell because someone else told it before.”

As the author of four books, Zurski has been sharing history since his first book, “The Wreck of the Columbia,” which was published in 2012. As a resident of Morton, Illinois, he loves telling regional stories that made a lasting impact on the people reading them. “UNREMEMBERED” allowed Zurski to branch out into global storytelling.

The prevalence of digital databases and online resources allowed Zurski to gather information at a much quicker rate, which made writing the “UNREMEMBERED” books more enjoyable.

“Research has become much more advanced–thank goodness,” Zurski said. “When I wrote ‘The Wreck of Columbia’ I was at the Peoria and Pekin libraries for days on end, going through their newspaper archives.”

Although researching and writing is a time-consuming process, Zurski wouldn’t trade it for anything.

“It’s really my joy, just writing books and sharing them,” he said.

Since “UNREMEMBERED Book 2” is centered around people that most readers are unfamiliar with, Zurski has a recommendation for the best way to read his book.

“Look at the back of the book first and see if you recognize any names,” Zurski said. “Read the book. Come back to it–and you’ll have all of these stories.”

Visit amazon.com or amikapress.com to purchase a copy of “UNREMEMBERED Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers & Influencers.”

A Book and a Bear Claw

A Book and a Bear Claw.

By Bill Thill

Ken Zurski‘s latest book, “Unremembered – Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers & Influencers” is available for purchase and set to street today, Monday 9-19-22.

It’s a brilliant piece of work.

Ken’s concept for “Unremembered” was to tell “Tales of the nearly famous and the not quite forgotten” and in this book he focuses on a key group of artists in the early part of the twentieth century, a time of prodigious creative output both here in America and in Europe.

If our current entertainment landscape did in fact have a genesis moment, the life and times of the people chronicled here are likely a big part of it.

Dancer Isadora Duncan, theatrical producer Charles Frohman (one of the men who built Broadway), the French sculptor Rodin, J.M. Barrie (the man who wrote Peter Pan), Maude Adams (the actress who played the part), Paris Singer (an unabashed pursuer of the ladies and scion of sewing machine wealth), Kathleen Bruce (an artist who would come to high social standing), the explorer of the antarctic Captain Robert Scott, Mary Desti (a woman who fled a harsh reality, taking her son, a future Academy Award winner, to a better life) are just a handful of the real-life characters that fill the book’s 249 pages.

The dreamers and doers of the era seemed to criss-cross the Atlantic with such regularity that, for the first time in history, the intersection of bold artistic ideas and the crossing of cultural and political boundaries created a new tapestry of shared entertainment experiences. That along with the the emergence of a more rapid style of hot-take celebrity journalism combined to create an environment where the subjects of the book became part of something that had never before existed; a tapestry of personalities that strongly influenced culture through the arts.

Whether this was purposeful on the part of the true life characters that make up the stories in the book, or an inadvertent result of their creative journey, is left for the reader to decide. What is clear is that Ken’s subtitle of “Actors, Artists, Entertainers and Influencers” uses that fourth descriptor of “Influencer” as a way of drawing a straight line from today, back more than 100 years ago, to a time when the modern definition of such a personality, sans the term, could be said to have emerged.

Then, as with today, fire creates both light and heat and we, as the mass audience, are inexorably drawn to both. The stories in the book inevitably draw the reader to a conclusion that is almost as unsettling as it is obvious. These people, our predecessors in possession big dreams, wide fame and broad cultural impact, are kindred souls to many of us today whether or not you work in the arts or entertainment.

Breathing life into the sometimes forgotten past can be unsettling because it tears at a bias regarding our place in the world. It’s a natural and common bias that exists within each of us due to the fact that our world didn’t begin until the day we were born. By direct experience of the here and now it is only our lives that are filled with the bright colors of each new day. We witness and interpret our existence in “real” and immediate time and are faced with the promise, mystery and potential peril of all that is yet to occur.

From such a perspective everything that came before our grand existence is, by default, foreign to us. The language, the wardrobe, the technology and all that goes with those from whom we are a century advanced in calendar time is, in a temporal sense, antiquated and therefore inert. Such thinking elevates the here and now to an exalted position. After all, when we read histories, remembered or not, we often know how the stories and the fates of of our players will end. What could be more godlike than that?

Ken Zurski’s great gift as a storyteller is that he presents as a chronicler of personal histories that have been muted by the veil time. Once the reader is drawn in, however, we are surrounded by the flesh and blood of his subjects, their plots and passions, their loves and losses, the very fire of their lives which leads us to a renewed but once again shocking realization that some very significant parts of everything we consider to be our unique reality has been forged by all that came before. Much of our “here” stands on the foundation built by those who well preceded us and our “now” is more fleeting and borrowed than we might comfortably wish to comprehend within the daily practice of our lives.

Whether or not you work in entertainment or the media, in some cases, the individuals profiled in “Unremembered: Book 2” may be the exact people who built the foundation on which many of your “original thoughts” now stand. Acknowledging the true scope of history, while ultimately life affirming, is not for the timid.

That being said, I had difficulty with the final handful of chapters in this book.

First a bit about author Ken Zurski. Ken is a media professional who has made his living in the field of communications. He’s been a daily radio presence in the Midwest for several decades now. My favorite anecdote about Ken is that in his earliest days on big stick radio in Chicago he was known, on air, as Grant Parke. No, not like the park with the big fountain in the middle of the Loop Grant Park, of course not. Mind the “e” at the end of that name! Meanwhile, Chicago radio is nothing if not “broad shouldered” in the art of equally broad, tongue firmly in cheek, comedy and commentary.

For Ken to have been professionally birthed in such an environment and to observe, on a daily basis, the ebb and flow of his industry has, no doubt, enhanced his gifts as a storyteller. What’s fascinating about Ken’s journey is that he’s managed to merge his instinct for journalistic inquiry with the desire to tell campfire stories that have never before been told.

A few years ago, I told Ken outright that what he was doing as a storyteller would soon cause the world to beat a path to his door. With a series like “Unremembered” Ken is not only doing a great job of telling the stories but he’s also gathered the wood and sparked the flame. The History Channel has recently reached out to Ken and he’s already on his way to another chapter in his own evolving story. I think he’d appreciate it if you friended him on Facebook and followed along. For Ken there are many good things yet to come.

Now, for the sake of balance, let me explain my troubles with the last few chapters of “Unremembered Book 2: Actors, Artists, Entertainers & Influencers.”

Many things in life can bring us pleasure, a cup of coffee on an overcast day, a glazed bear claw that’s bigger than a plate, a good book that’s so well written, alive with characters and full of information that’s new to us that it’s hard to put down. I’ve experienced all of these things since Ken gifted me the opportunity to read his book weeks before it went into wide release. However, I am also a dyed in the wool gratification delayer and therein lies the rub.

I only took a bite of the bear claw because there is no way I was going to indulge to the finish anything that would counteract my recent workouts. I just sipped at the coffee, until it grew cold, mindful that too much caffeine is not my friend. And, just days before I snapped the photo beneath this post, I had stopped reading Ken’s book a few dozen pages short of the finish.

I tend to savor what I enjoy by invoking moderation or by slowing down their inevitable conclusion. I didn’t want the boat to sink. I didn’t want the expedition to fail. I wanted the children to grow and live to tell their own stories and I sure as hell didn’t want that car to drive off while her long scarf was anywhere near its spoked wheels. I didn’t want this book to end.

I read the final pages of “Unremembered” apart from the rest. I savored them. I knew I would have to because of my innate yearning for the show to go on. Because, you see, the show must always go on.

The actors, artists, entertainers and influencers brought back to life by Ken’s brilliant work are no doubt smiling down on the man who, more than a century later, has given them another curtain call. The irony of “Unremembered” is that you won’t soon forget it.

If you’d like to purchase Ken’s book I’ll place a link in the comments. Show people should definitely read this book and suggest it for the shelves of their favorite bookstore. You’ll quickly recognize the “sliding doors” effect of your own creative journey and of all the things that only exist, in the particular way they do, because of your personal contribution.

Congratulations, Ken! I thoroughly enjoyed the read.

Bill Thill is a producer, director, writer & industry podcaster based in Santa Monica, California

I Am Superman

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

After a court martial for violating the 96th Article of War which prohibits public criticism of the military by an officer, Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson left the US Calvary in 1923 and became a pulp writer and entrepreneur instead.

While looking for a distinctive character to highlight his new Detective Comics series, Wheeler-Nicholson sent a letter to comic book writer Jerry Siegel.

“We want a detective hero called ‘Slam Bradley’” he wrote. “He is to be an amateur, called in by the police to help unravel difficult cases.”

Siegel and co-creator Joe Shuster used “Slam Bradley” as a trial run for another character they thought had more appeal.

They named the new character “Superman.”

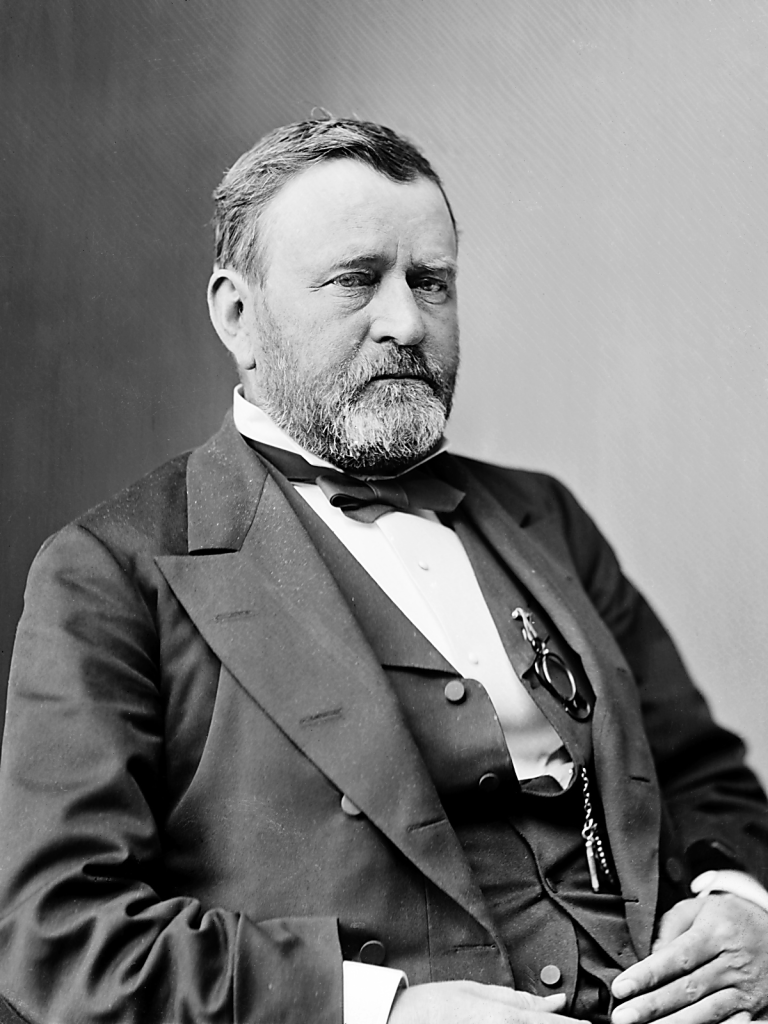

‘Gentleman’ Jim Fisk, Jay Gould, the Greedy Gold Takeover, and How President Grant Stopped It.

By Ken Zurski

Jim Fisk was a larger than life figure in New York both physically and socially. A farm boy from New England, Fisk worked as a laborer in a circus troupe before becoming a two-bit peddler selling worthless trinkets and tools door to door to struggling farmers. The townsfolk were duped into calling him “Santa Claus” not only for his physical traits but his apparent generosity as well. When the Civil War came, Fisk made a fortune smuggling cotton from southern plantations to northern mills.

So by the time he reached New York, Fisk was a wealthy man. He also spent money as fast as he could make it; openly cavorted with pretty young girls; and lavished those he admired with expensive gifts and nights on the town. Fisk never hid behind his actions even if they were corrupt. He would chortle at his own genius and openly embarrass those he was cheating. He earned the dubious nickname “Gentleman” for being polite and loyal to his friends.

Friends like Jay Gould

A leather maker turned New York railroad owner, Gould was the youngest of six children, the only boy, and a scrawny one at that; growing up to be barely five feet tall. What he lacked in size, however, he made up for in ambition.

A financial whiz even as a young man, Gould started surveying and plotting maps for land in rural New York, where he grew up. It was tough work, but not much pay, at least not enough for Gould. In 1856 he met a successful tanner – good work at the time – who taught Gould how to make leather from animal skins and tree bark. Gould found making money just as easy as fashioning belts and bridles. He found a few rich backers, hired a few men and started his own tanning company by literally building a town from scratch in the middle of a vacant but abundant woodland. When the money started to flow, the backers balked, accusing Gould of deception. Their suspicions led to a takeover. The workers, who all lived quite comfortably in the new town they built and named Gouldsborough, rallied around Gould and took the plant back by force, in a shootout no less, although no one was seriously hurt.

Gould won the day, but the business was ruined. By sheer luck, another promising venture opened up. A friend and fellow leather partner had some stock in a small upstate New York railroad line. The line was dying and the stock price plummeted. So Gould bought up the stock, all of it in fact, with what little earnings he had left, and began improving the line. Eventually the rusty trail hooked up with a larger line and Gould was back in business. He now owned the quite lucrative Erie Railroad.

Ten years later, in 1869, Gould got greedy and turned his attentions to gold.

Gold was being used exclusively by European markets to pay American farmers for exports since the U.S currency, greenbacks, were not legal tender overseas. Since it would take weeks, sometime months for a transaction to occur, the price would fluctuate with the unstable gold/greenback exchange rate. If gold went down or the greenback price went up, merchants would be liable -often at a substantial loss – to cover the cost of the fluctuations. To protect merchants against risk, the New York Stock Exchange was created so gold could be borrowed at current rates and merchants could pay suppliers immediately and make the gold payment when it came due. Since it was gold for gold – exchange rates were irrelevant.

Gould watched the markets closely always looking for a way to trade up. He reasoned that if traders, like himself, bought gold then lent it using cash as collateral, large collections could be acquired without using much cash at all. And if gold bought more greenback, then products shipped overseas would look cheaper and buyers would spend more. He had a plan but needed a partner.

He found that person in “Gentleman Jim Fisk.”

Fisk and Gould were already in the business of slippery finance. Besides manipulating railroad stock (Fisk was on the board of the Erie Railroad), they dabbled in livestock and bought up cattle futures when prices dropped to a penny a head. Convinced they could outsmart, out con and outlast anyone, it was time to go after a bigger prize: gold. There was only $20 million in gold available in New York City and nationally $100 million in reserves. The market was ripe for the taking and both men beamed at the prospects.

But the government stood in the way. President Grant was trying to figure out a way to unravel the gold mess, increase shipments overseas and pay off war debts. If gold prices suddenly skyrocketed, as Gould and Fisk had intended, Grant might consider a proposed plan for the government to sell its gold reserves and stabilize the markets; a plan that would leave the two clever traders in a quandary.

Through acquaintances, including Grant’s own brother-in-law, Gould and Fisk met with the president. In June of 1869, they pitched their idea posing as two concerned (a lie) but wealthy (true) citizens who could save the gold markets and raise exports, thus doing the country a favor. They insisted the president let the markets stand and keep the government at bay. Fisk even treated the president to an evening at the opera – in Gould’s private box. The wily general may have been impressed by the opera, but he was also a practical man. He told the two estimable gentlemen that he had no plans to intervene, at least not initially. But Grant really had no idea what the two shysters were up to.

A few months later, when Fisk sent a letter to Grant to confirm the president’s steadfast support, a message erroneously arrived back that Grant had received the letter and there would be no reply. The lack of a response was as good as a “yes” for Fisk. Grant was clearly on board, he thought.

He was wrong.

On September 20th, a Monday, Fisk’s broker started to buy and the markets subsequently panicked. Gold held steady at first at $130 for every $100 in greenback, but the next day Fisk worked his magic. He showed up in person and went on the offensive. Using threats and lies, including where he thought the president stood on the matter, Fisk spooked the floor.

The Bulls slaughtered the Bears.

Gold was bought, borrowed and sold. And Fisk and Gould, through various brokers, did all the buying. On Wednesday, gold closed slightly over 141, the highest price ever. In his typical showy style, Fisk couldn’t help but rub it in. He brazenly offered bets of 50-thousand dollars that the number would reach 145 by the end of the week. If someone took that sucker proposition, they lost. By Thursday, gold prices hit an astounding 150. The next day it would reach 160.

Then the bottom fell out.

At the White House, Grant was tipped off and furious. On September 24, a Friday, he put the government gold reserve up for sale and Gould and Fisk were effectively out of business. Thanks to the government sell off, almost immediately, gold prices plummeted back to the 130’s.

Many investors lost a bundle, but the two schemers got out mostly unscathed.