Uncategorized

Dying for King, Country and Spices and Spices and Spices and Spices

By Ken Zurski

In 1517, King Charles I of Spain, who had just assumed the throne at the tender age of eighteen, was approached by a Portuguese explorer named Ferdinand Magellan.

In 1517, King Charles I of Spain, who had just assumed the throne at the tender age of eighteen, was approached by a Portuguese explorer named Ferdinand Magellan.

Rejected by his own country, Magellan made the young King an offer: Let him sail around the world and find a direct route to Indonesia, once successfully navigated by Christopher Columbus.

Columbus’s four voyages for Spain, among other revelations, claimed new lands, including one which was named after another Italian explorer Amerigo Vesspucci.

Charles found Magellan’s plan intriguing. After all, great riches awaited any King who could bring back the precious spices like cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves which grew in abundance on the elusive islands.

If Magellan could find a way to get the spices back to Charles, Spain would reap the rewards and rule the spice trade. Charles wholeheartedly approved the voyage and ordered five ships and a crew of nearly 300 men.

In 1519, Magellan set sail from Seville.

Four years later, limping back to port, only one ship named Victoria returned. Every other ship was lost including most of the men. Even Magellan was gone, hacked to death in a fierce battle with a native tribe.

Despite this, the King was pleased.

The tragic news of the lost ships and crew was irrelevant. The Victoria had returned with a cargo of 381 sacks of cloves, the most coveted of all spices.“No cloves are grown in the world except the five mountains of those five islands,” explained the ships diarist.

The tragic news of the lost ships and crew was irrelevant. The Victoria had returned with a cargo of 381 sacks of cloves, the most coveted of all spices.“No cloves are grown in the world except the five mountains of those five islands,” explained the ships diarist.

Charles questioned the returning men on mutiny claims and other charges of debauchery, but it didn’t matter.

He paid the royal stipends to survivors, basked in his clove treasure, and set in motion plans to put another crew back in route to the islands.

The First Multi-Book Reader Dates Back to the 16th Century

By Ken Zurski

Agostino Ramelli was a military engineer which meant he wore an armored suit and carried a sword like the rest of his fellow combatants, but used his brain rather than brawn on the battlefield.

This came in handy during the 16th century French Wars of Religion when the Italian born Ramelli went to France, took up arms with the Catholic League, and was captured by the Protestants (Huguenots).

While incarcerated, Ramelli not only found a way to break out, but in as well. After he escaped – or was exchanged – Ramelli returned and breached the fortification by mining under a bastion. From that point on, he called himself “Capitano” and dedicated his life to, well, figuring things out.

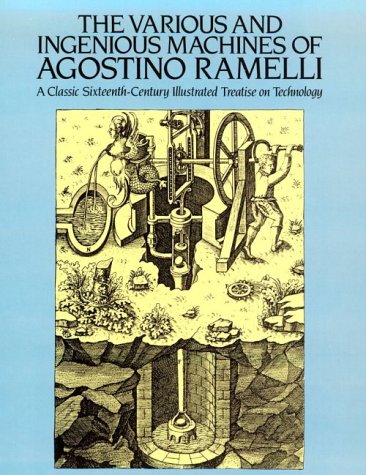

In 1588, he released a book titled, Various and Ingenious Machines of Capitano Ramelli. The expertly illustrated book was a compilation of 195 machines that made laborious tasks more practical. Many of the machines lifted things in crafty ways, like water, or solid objects, like doors off their hinges. One machine milled flour using rollers rather than stones.

Then there was the Book Wheel.

“This is a beautiful and ingenious machine, very useful and convenient,” Ramelli bragged about the large contraption which allowed a person to sit and read several different books without actually picking them up.

By convenient, he meant for those suffering from gout, a painful joint disease which made walking or standing difficult. A noble gesture, for sure, but the wheel itself, while complex, was also bulky and cumbersome. So it is doubtful Ramelli designed it strictly for its practicality.

Nevertheless, its usefulness is left up to the user to decide. The operator remains seated while the books, eight in all, each come to the front by turning the wheel.

Ramelli was especially proud of the gearing system that kept the books constantly level to the ground. He built an intricate gear for each slot and prominently featured a diagram in his book to explain the complicated design. The impressive technology was similar to that used in an astronomical clock.

It was also wholly unnecessary.

A simple swivel pivot and gravity could do the trick just as engineer George Ferris would prove many centuries later in a similar design that carried people rather than books.

Speculation is Ramelli knew this application applied to his Book Wheel, but as a mathematician, and a bit of a swank, he couldn’t help himself.

The English Boxing Champion Who Gets His Bell Rung Everyday

By Ken Zurski

On July 21, 1835 Benjamin Caunt and William Thompson, two of England’s best known boxers and biggest rivals, faced off in a test of strength, will and endurance, typical of a boxing match at the time.

Thompson, considerably lighter and shorter than the 6-foot, 2-inch, 250-pound Caunt, was known as much for his relentless taunting as he was for his fighting. During the bout, Thompson would chant clever but insulting sing-song rhymes directed at his opponent’s wife or mother. Usually the submissive jeers worked to Thompson’s advantage, but Caunt was different – or was he?

For twenty-two rounds, Caunt endured Thompson’s verbal assaults until he finally had enough. During a short break, Caunt walked over to the opposing corner and blindsided Thompson in the head while he sat, ending the fight on a foul and sending the unsuspecting winner slumping to the ground in a heap.

A rematch would take place three years later.

In that contest, Caunt had the advantage early on, but in the 13th round lost his cool again. He began to strangle his opponent with both hands until Thompson nearly passed out. Thompson’s corner crew stormed the ring to help the struggling boxer and subdue Caunt. In defense, Caunt pulled a rope spike out of the ground and began waving it in front of him. Caunt eventually backed off and Thompson was revived with a few sips of brandy. The bout continued until the 75th round when Thompson finally hit the ground from exhaustion. Caunt was declared the winner and returned to his hometown of Nottingham City where he was treated to a hero’s welcome and crowned the new heavyweight champion of England.

The two rivals third and final match in 1845 was mostly Thompson’s to lose. Caunt was hit so hard and bleeding so profusely near the eye that in the 93rd round he retired to his corner to sit. The referee, however, never called for the break and Caunt was ordered to continue. He didn’t. Thompson won by a deliberate foul. Following the embarrassing defeat, Caunt went into a semi-retirement, but his legacy did not.

Despite his even record of wins and loses, Caunt was a giant of a figure in England. Not only due to his a physical attributes, tall and solidly built, but his affectionately playful manner and “booming” laugh too. “A huge, slow-witted, beef-raised pugilist of tremendous powers,” a newspaper recounted in 1910, “who gained prominence through sheer muscle and pluck.” Caunt earned the nicknames “Tokard Giant” referring to his English birthplace, “the bare-knuckled boxer” (there were no gloves used), and the moniker that seemed to stick more than others: “Big Ben.”

“Big Ben” was lured back into the ring one more time in 1857 at the age of 42 to settle a dispute involving the two combatants wives. After 60 rounds both men were too exhausted to continue and declared it a draw.

Four years later, Caunt died from pneumonia.

But his story doesn’t end there. In fact, it goes back 20 years to 1834, when a fire ripped through Westminster Palace. Ten years later, the rebuilding committee decided to add a massive clock tower to the new design, including a tolling bell. In May of 1859, after several construction delays and a few broken casts, the bell rang out for the first time.

Shortly after its unveiling, a Parliamentary committee was formed to come up with a name for the bell, similar to York Minister’s “Great Peter” named for the saint, of course, and the church which bears it’s name.

One man on the committee towered above the rest, not only in size but in stature as well. His name was Sir Benjamin Hall. He was the Chief Lord of Woods and Forrests and he stood a whopping 6-foot-4 inches tall.

Hall would typically send the room into a frenzy with his confrontational debates and fiery speeches. During one raucous session dominated by Hall, an exasperated colleague stood up and said: “Why not call him ‘Big Ben’ and be done with it.” No one knows for sure if the acknowledgement was in reference to Hall’s larger-than-life demeanor or the bell. The nickname stuck and Hall apparently sold the idea that the bell was named after him. He died in 1867. The story, however, comes with a mix of skepticism and doubt. Not a word of it was documented. It’s hearsay and most of it was Hall’s doing, not much more.

The more plausible explanation, and the one supported today, is that the bell in London’s iconic Elizabethan Tower is named after the boxer, Benjamin Caunt. That’s because Caunt, like his size, was associated with heavy things, often the heaviest or biggest of things, or in this case, the nearly 14-ton bell. It must be a “Big Ben,” like the famous boxer, many surmised.

But being bigger was not always better.

In October 1859, several months after the great bell was installed, it cracked. The striking hammer was to blame. Either it was too strong or the bell was hung too rigidly, no one was quite sure. Whatever the reason, it was ridiculed in the press for being a mammoth failure, at least initially. “There is no more melancholy looking object than a large public clock which wont go.” the London Times sarcastically reported. Criticism of the time and expense it took to put up the bell was replaced by even harsher objections to how much more time and expense it would take to fix it. “An old adage tells us the fate of the best broth with too many cooks to prepare it,” the Times reported, openly blaming poor management and craftsmanship for the bell’s initial failure.

“In the name of common prudence,” the Times continued, “let the contract for the next bell be given to some of our eminent bell founders who have passed their lives and realized fortunes in the manufacture of bells of all kinds.”

Whether Caunt knew the bell was named after him is not known. Perhaps based on its ineffectiveness at first, he wanted nothing to do with it. When “Big Ben” tolled for the first time, Caunt, who was likely in Nottingham City – a distance of 175 kilometers to London – would have never heard it.

By the time the recasted bell rang again, nearly two years later, he was dead.

How the Civil War Changed Baseball Forever

By Ken Zurski

Conventional wisdom would suggest that the start of the Civil War in 1861 slowed down the progress of a game like baseball, a sport that was gaining popularity in the years before the conflict began.

And that is true, to a point.

Inevitably as men heeded the call to serve, there just weren’t as many players to take the field. But there were reserves to take their place, especially in the well populated state like New York, which holds the distinction of introducing the world to Base Ball (then written as two words).

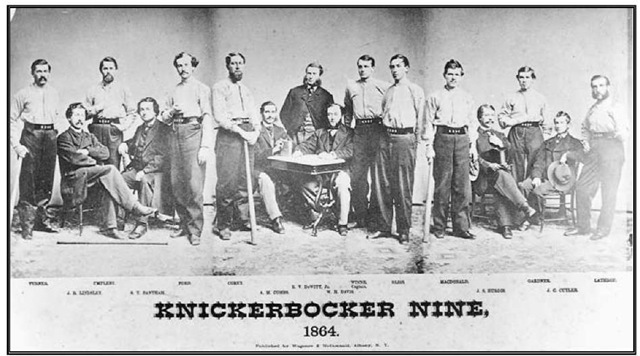

While bat-and-ball type games were popping up throughout the country, in New York, an actual team called the Knickerbockers emerged in the 1840’s. While not trailblazers in creating the game, they can be considered pioneers when it comes to the sport. The Knickerbockers actually made and followed rules.

Other teams formed and crowds grew.

Then came the war.

Although pick-up games continued, the sport shifted to the battlefront instead. “Each regiment had its share of disease and desertion; each had it’s ball-players turned soldiers,” remembered George T Stevens, of the 77th Regiment, New York Volunteers.

Union soldiers would play a good “game of nines” to help pass the time.

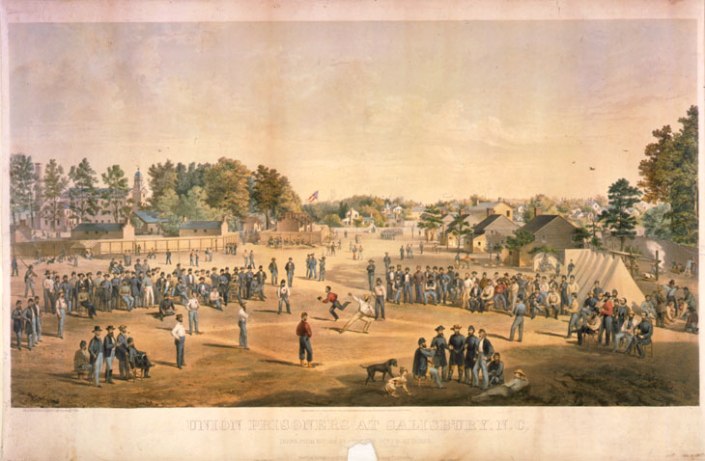

Otto Boetticher was a Union prisoner at Salisbury, North Carolina. In 1861, at the age of 45, he enlisted in the 68th New York Volunteers and left his job as a commercial artist. The following year he was captured and ended up in Salisbury before a prisoner swap set him free a few months later. Before leaving, Boetticher did a drawing of a prisoner game of baseball.

Boetticher’s drawing, released in 1864, was hardly representative of prison camp descriptions at the time. “Despite the bleak realities of imprisonment,there is a sense of ease and contentment in the image, conveyed in part by pleasures of the game, the glowing sky and sunlight, and the well-ordered composition,” one assessment of the drawing goes.

Boettchler’s lighthearted look at prisoner life wasn’t his fault. The harsh reality of the POW camps would come later with the woeful Libby and Andersonville among others where the prisoner population grew by thousands and unsanitary and overcrowded conditions led to widespread starvation and sickness. Early on, however, the captured soldiers waited for their name to be called.

Why not play a spirited game of baseball?

Boetticher’s print may have been from a July 4th game, when prisoners were allowed to celebrate the nation’s holiday, as one prisoner described, with “music, sack and foot races and baseball.” But if weather permitted and “for those who like it and are able,” baseball was played everyday.

Some might think Boetticher’s depiction of prison life is more deception than reality. But prisoner recollections support the claim that despite the animosity between them, a game of baseball was good fun for both sides.

“I have never seen more smiles today on their oblong faces,” William Crosley a Union sergeant in Company C wrote describing Confederate captors watching a match at Salisbury. “For they have been the most doleful looking set of men I ever saw.”

Once the conflict was over, the game itself was in for an overhaul. Many of the older players who went off to war, were either injured, weary, or worse. That’s when younger players joined in. Skills improved, rules were implemented and the game became more about the playing and the winning rather than just a friendly “game of nines”

Base ball became Baseball – a legitimate competitive sport.

Play ball!

When America Reelected a Very, Very Sick Man

By Ken Zurski

In November of 1944, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was reelected to a fourth term as president of the United States, an unprecedented, but not unexpected achievement for the New York businessman turned politician who garnered increasing support of the American people during his twelve years in the Oval Office.

In November of 1944, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was reelected to a fourth term as president of the United States, an unprecedented, but not unexpected achievement for the New York businessman turned politician who garnered increasing support of the American people during his twelve years in the Oval Office.

Although a handful of past presidents had tried, none had served more than two terms, a limitation the nation’s first president General George Washington had advised others to follow. But at the time, there were no restrictions. FDR, as he was famously called, broke new ground when he won a third term. A fourth term he felt during a time of war was just as important.

The voting public agreed. Roosevelt, a Democrat, beat Republican challenger Thomas Dewey in what can be considered even by today’s standard as an overwhelming victory.

The voters, however, had no idea – at least not officially – that they had elected back into office a man who was living on borrowed time.

In the months, even years, leading up to the 1944 election, the American people heard rumors and speculation about the president’s health. Roosevelt suffered from polio which limited his mobility, but in 1944 his appearance seemed to worsen. He looked feeble and weak; his eyes were often red and swollen; and his movements were slow and calculated.

Behind the scenes, there were concerns, but no immediate panic. Dr. Frank Howard Lahey, a respected surgeon known for opening a multi-specialty group practice in Boston, was brought in for a consultation. Lahey’s connection with the Navy’s consulting board led him to the White House. After a careful examination, Lahey informed Roosevelt that he was in advanced stages of cardiac failure and should not seek a fourth term. Even went so far as to warn Roosevelt that if he did win reelection, he would likely die in office. Roosevelt listened but did not follow Lahey’s advice. He felt it was his duty to continue.

In April of 1945, less than three months after being sworn in for the fourth time, Roosevelt was dead.

The president’s death took most Americans by surprise. That’s because shortly after being reelected, Roosevelt’s personal physician at the time, the surgeon general of the U.S. Navy, Dr. Ross McIntire, helped quell public fears by proclaiming FDR was feeling fine. But others could visibly see the president’s decline.

At the White House, Vice President Harry Truman was sworn in and questions were asked: Why didn’t the voting public know the truth about Roosevelt’s health?

In hindsight, Lahey’s report seemed to be the most truthful and forewarning. But information between a doctor and client is private and confidential. The White House only asked Lehay to consult the president. Whether the details were released was up to Roosevelt and his staff. The report was concealed and only came to light nearly six decades later. Lehay himself could have spoke up, but chose to remain silent and honor the patient-doctor confidentiality agreement.

Instead, what was disclosed to the public was mostly misleading. It included a glaringly deceptive assessment of the president’s condition in the months before the election.

In March 1944, the White House announced a report by Dr. McIntire, which claimed the 62-year-old Roosevelt was looking “tired and haggard” due to the stress and strain of the war years and nothing more.

“In my opinion,” McIntire added, “Roosevelt is in excellent condition for a man of his age.”

He was either astonishingly wrong or lying.

For a Long Time, Nearly all U.S. Presidents Had Facial Hair. And Then They Didn’t

By Ken Zurski

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, was the first commander-and-chief to have facial hair.

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, was the first commander-and-chief to have facial hair.

Surprised?

Actually by being the first to sport a beard, Lincoln started a trend that lasted nearly 50 years. But even Lincoln’s beard was an afterthought. Lincoln never had facial hair as an adult and only let his whiskers go after a receiving a letter from an 11-year-old girl named Grace Bedell who suggested the president-elect should grow one. “For your face is so thin,” she wrote.

Lincoln reluctantly obliged.

After Lincoln, and in the eleven presidencies that followed, only Andrew Johnson and William McKinley chose to go clean shaven. The rest had either a beard, mustache or both. Chester Arthur was one. The 21st president, had a classic version of sidewhiskers, an extreme variation of the muttonchop, or side hair connected by a mustache.

After Lincoln, and in the eleven presidencies that followed, only Andrew Johnson and William McKinley chose to go clean shaven. The rest had either a beard, mustache or both. Chester Arthur was one. The 21st president, had a classic version of sidewhiskers, an extreme variation of the muttonchop, or side hair connected by a mustache.

But it didn’t last.

The last president to have facial hair is William Howard Taft (mustache) in 1909.

Woodrow Wilson, who was always impeccably coiffed and dressed, was next. President Wilson shaved everyday and ended the trend.

Woodrow Wilson, who was always impeccably coiffed and dressed, was next. President Wilson shaved everyday and ended the trend.

Many claim the invention of Gillette’s safety razor in the early 1900’s had something to do with the change. Suddenly shaving was easier and facial hair in general went out of style. Plus, the military banned beards too. This was not the case during the Civil War or the Spanish -American War, led in part by a future president, Teddy Roosevelt, who sported a bushy mustache.

Regardless of why it ended, from Wilson on, rarely a stitch of facial hair has been spotted on a president’s face. (You can add many vice-presidents to that list too.) And despite a surge in popularity for beards today, that likely wont change with the election of the 45th president. Donald Trump has never sported facial hair and well, Hillary Clinton, who could become the first woman president, makes the point moot.

But even something as trivial as a beard has controversy.

Some argue that John Quincy Adams, not Lincoln, should be considered the first president to have facial hair. If so, that would pull the history of presidents and hair growth back nearly four decades.

Some argue that John Quincy Adams, not Lincoln, should be considered the first president to have facial hair. If so, that would pull the history of presidents and hair growth back nearly four decades.

But not to be.

While Adams certainly had hair on his face, his chops, which extended off his ears and sloped down to his chin, were considered sideburns instead.

Before There Were Child Labor Laws, There Were Spraggers.

By Ken Zurski

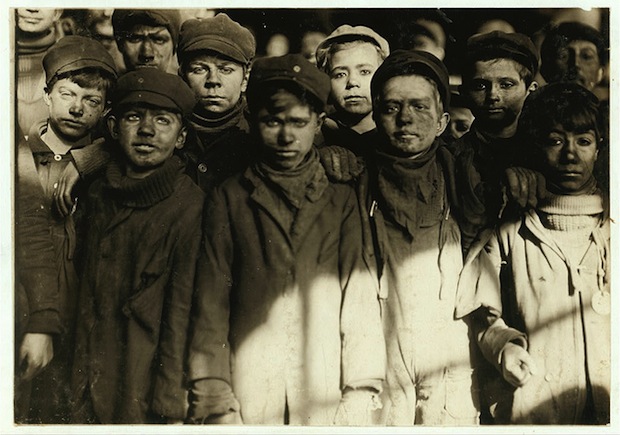

In the mid 19th century, coal mining rail cars used to carry large amounts of the valuable black rock between underground multi-leveled work chambers had no braking system. If one went down an incline too quickly, it simply kept going like a roller coaster until it derailed and spilled its contents in the process. Since miners were paid by the weight of cars they unloaded, this would cost them time and money. To keep this from occurring, boys as young as six years of age were hired to help the cars come to a stop.

In the mid 19th century, coal mining rail cars used to carry large amounts of the valuable black rock between underground multi-leveled work chambers had no braking system. If one went down an incline too quickly, it simply kept going like a roller coaster until it derailed and spilled its contents in the process. Since miners were paid by the weight of cars they unloaded, this would cost them time and money. To keep this from occurring, boys as young as six years of age were hired to help the cars come to a stop.

They were called “spraggers.”

A sprag was a stick of wood, not quite as long as a baseball bat. Each boy carried several sprags and were positioned in areas where the cars, sometimes eight in a row, would roll down the slope. The boys would run alongside and jab the sprags into the spokes of the wheel. The sprags acted as brakes, slowing down the car until it stopped.

If this sounds dangerous, it certainly was. The sprags would get caught in the spoke and take an arm with it. Some boys lost fingers, or even hands. Some of the more adventurous types would jump on the side of the rolling car for fun and hold on while another jabbed the sprag in the wheel. This broke up the monotony of the day, but if the car failed to stop, the unfortunate passenger usually went with it, careening out of control until it broke from the rail and smashed into the wall. Of course, being a “spragger” meant you were one the fastest and most agile of the young crew. Other boys would work in the picking room as “breakers,” sorting refuse from the coal; still others opened and closed heavy doors as the coal cars approached, called “nippers.”

For many boys of this era, working in the coal mine was an honor bestowed upon by their ancestors. After all their father and grandfathers had grown up in the mines and in all likelihood their future as a fellow miner was already set. You can imagine the mothers, even if they protested, had little say in the matter. The coal mining industry was literally a “well-oiled machine” that worked if all parts were in place – even at the expense of using children to keep it moving. “He never got used to the noise, the dust, the threat of danger,” writes author Susan Campbell Bartoletti in her book Growing Up In Coal Country, “He was proud to earn money for his family. That was the life of a miner’s son.”

For many boys of this era, working in the coal mine was an honor bestowed upon by their ancestors. After all their father and grandfathers had grown up in the mines and in all likelihood their future as a fellow miner was already set. You can imagine the mothers, even if they protested, had little say in the matter. The coal mining industry was literally a “well-oiled machine” that worked if all parts were in place – even at the expense of using children to keep it moving. “He never got used to the noise, the dust, the threat of danger,” writes author Susan Campbell Bartoletti in her book Growing Up In Coal Country, “He was proud to earn money for his family. That was the life of a miner’s son.”

Although no safety records were kept back then, we can assume there were deaths, perhaps many. Eventually in the late 1800’s state laws were passed that prevented children under twelve to work in a mine. In 1902, that was raised to fourteen. But for many tight-knit mining communities there were no birth certificates, so boys younger than fourteen were passed off as simply “small for their age.”

Although the act of using children in dangerous places was already being condemned by early trade unions and women’s groups, the movement gained more traction in 1912. That’s when The Children’s Bureau was created within the Department of Commerce and Labor and later transferred to the nearly created Department of Labor.

By then reports of children being maimed or worse were surfacing. One boy, Manus McHugh, whose job it was to oil the mining breaker machinery, reportedly wanted to finish the day so badly he attempted to oil the machine while it was still running. His arm got caught first. In the investigation that followed. McHugh’s death was blamed on disobedience. “Boys will be boys and must play,” it stated. “Unless they are held in strict discipline.” No legal action was taken.

The inaugural federal child labor law known as the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act was signed by President Woodrow Wilson on September 1, 1916, a Friday, and ironically the start of the long Labor Day weekend, since Labor Day always fell on the first Monday of September. But the bill only regulated child labor by banning the sale of products used by factories that employed children under fourteen. It was ruled unconstitutional in 1918.

The first minimum age requirement of a minor, part of the Fair Labor Standards Act, was not federally mandated until 1938.

Father Marquette Mentioned a Parrot Among Other Strange Birds in Illinois

By Ken Zurski

In 1674, while exploring the Illinois River for the first time, French Jesuit missionary Father Jacques Marquette wrote in his journal: “We have seen nothing like this river that we enter, as regards its fertility of soil, its prairies and woods; its cattle, elk, deer, wildcats, bustards, swans, ducks, parroquets, and even beaver.”

Certainly the reference to parroquets, or perroquets, (French for parrot) raises some eyebrows. But a species called the Carolina Parrot, now extinct, did inhabit portions of North America, as far north as the Great Lakes, as early as the 16th century.

More puzzling, however, is the mention of the bustard.

Even the Illinois State Museum in the state’s capitol of Springfield questions this unusual reference.

“What is a Bustard?” the Museum sign asks in an exhibit showcasing birds native to Illinois, then answers: “We’re not sure.”

Of course, the bustard is a real bird. In Europe and Central Asia it is more commonly known. In North America? It just doesn’t exist. But did it at one time? According to the Museum’s notes, several French explorers described bustards as being common game birds of Illinois and said they resembled “large ducks.”

Large indeed.

A Great Bustard can stand 2 to 3 feet in height and weigh up to 30 pounds making it one of the heaviest living animals able to fly. Its one distinctive feature, besides its size, is the gray whiskers that sprouts from its beak in the winter.

Father Marquette was more a man of the cloth than a scientist. His mission was to preach to the Illinois Indians or “savages” as he calls them. Along the way, however, he described the scenery and game in detail. The “bustard” comes up quite often in his journal. He even refers to hunting them, possibly eating them too. “Bustards and ducks pass continually,” he wrote.

Perhaps, as some suggest, Marquette was describing a common wild turkey. His recollections seem to imply they were airborne, which wild turkeys can do, despite the myth that they cannot fly (the “fattened” farm turkey – the one we use for Thanksgiving – does not fly).

The Illinois State Museum goes even further by speculating that the bird Marquette was referencing was not a bustard at all, but the Canada Goose which is similar in size and appearance to the Great Bustard.

But, as the Museum concedes, even that is “open to question.”.

The Ten-Million Dollar Question

By Ken Zurski

For a man whose mission it was to relinquish his entire fortune before his death, Andrew Carnegie still had plenty of money left when he passed in 1919 at the age of 83. That’s no indictment of a man who built a massively successful business, became the richest man in America, and devoted his later years to giving it all back. It was a noble thing to do. But Carnegie had made so much capital that even he found it difficult to allocate the funds sufficiently.

So he asked for help.

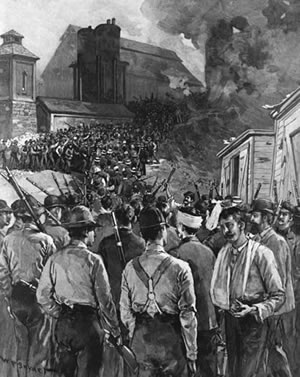

Carnegie grew up poor in Scotland, came to America, and amassed millions in the steel industry. Along the way, he made just as many enemies as dollars. Like many so-called tycoons of his time, Carnegie was accused of cutthroat practices which sacrificed workers’ rights for the bottom line. The Homestead Strike of 1892 was due to a dispute between steel workers at Carnegie’s Homestead, Pennsylvania plant and management which refused to raise workers’ pay despite a windfall in profits. The riot that followed is still one of the bloodiest labor confrontations in history. Ten men were killed in the melee and Carnegie who continued production with nonunion workers, was blamed for the uprising.

Carnegie viewed it differently than the workers. He believed that reducing production costs meant lower prices to consumers. Therefore, he theorized, the community as a whole profited, not the unions. It was a slippery slope. But, many asked, was it worth men dying for?

Carnegie, of course, thought of himself as a benefactor and did not apologize for becoming a wealthy man. When he retired, however, he made it clear that being rich was only relative: “Man must have no idol and the amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry! No idol is more debasing than the worship of money! Whatever I engage in I must push inordinately; therefore should I be careful to choose that life which will be the most elevating in its character.”

Carnegie didn’t hand out money haphazardly. He spent it on things and places that moved him. Among other worthy causes, the most prominent were funds for more schools – especially in low income communities – and the building or expansion of public libraries. In each case, he released the money only after specific demands were met, each one designed to make sure none of it went to waste. Carnegie had final approval.

In 1908, at the age of 72, with millions more left to give, Carnegie wrote a letter to people he admired. It was in effect an offer disguised as a question: “If you had say five or ten million dollars (close to 5-billion today) to put to the best possible use,” Carnegie asked, “what would you do with it?” Many of the correspondence were business leaders and some were presidents of institutions already bearing the Carnegie name. Most responded in kind that the money should be used to continue fellowships. The letters were an indication that the burden of giving away a fortune was weighing heavy on Carnegie’s mind.

“The fact is that after spending about $50-million on libraries, the great cities are generally supplied and I am groping for the next field to cultivate,” Carnegie wrote President Theodore Roosevelt. “You have a hard task as present but the distribution of money judiciously is not without its difficulties also and involves harder work than ever acquisition of wealth did.”

Carnegie wrapped up the letter by pointing out the absurdity of that last line. “I could play with that and laugh,” he noted.

In the end, of course, Carnegie left enough money behind to take care of his wife and daughter. His loyal servants and caretakers were awarded pensions and his closest friends received substantial annuities.

Carnegie gave away an estimated $350 million dollars, but for the rest, he had one final request. After the will segments were dived up, nearly $20-million remained in stocks and bonds.

He bequeathed that amount to the Carnegie Corporation organization he proudly founded, and which still exists today.

(Sources: Andrew Carnegie by David Nasaw; various internet sites)