American history

A Brother’s Lamentation

By Ken Zurski

On April 15 1865, the day after President Lincoln was struck down by an assassin’s bullet, Edwin Booth, a popular stage actor in New York, was told his younger brother John had pulled the trigger.

Edwin was appearing in a “successful” show at the time and immediately asked that it shut down. “The news of this morning has made me wretched,” he wrote, “not only because of my brother’s crime, but because a most justly honored and patriotic ruler has fallen.”

Edwin and his brother were estranged. Politics and ideology had separated them, as it did the rest of the country. “When I told John I voted for Lincoln,” Edwin recalled, “he expressed deep regret.”

Edwin feared for his own life after news that another brother, Junius, also an actor, had been threatened by an angry mob in Cincinnati. “Whatever calamity may befall me and mine, my country, one and indivisible, has my warmest devotion,” Edwin explained before going into hiding.

In January the following year, friends urged him to return to the stage. He reluctantly agreed. As his favorite character, Hamlet, Edwin stepped in front of a packed theater.

He was greeted by a tremendous applause.

‘The Greatest Gift’ is a Story You Know Well

By Ken Zurski

In November 1939 Philip Van Doren Stern, an American author, editor and Civil War historian wrote an original story titled “The Greatest Gift,” a heartwarming Christmas tale about a man named George Pratt who gets a dying wish granted by a guardian angel that literally changes his life.

Stern’s story begins at an iron bridge as a despondent George leans over the rail:

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” a quiet voice beside him

said.George turned resentfully to a little man he had never seen

before. He was stout, well past middle age, and his round

cheeks were pink in the winter air as though they had just been

shaved. “Wouldn’t do what?” George asked sullenly.

“What you were thinking of doing.”

“How do you know what I was thinking?”

“Oh, we make it our business to know a lot of things,” the

stranger said easily.

Stern desperately tried to get his little story published, but it never sold. So in 1943, he made it into a Christmas card book and mailed 200 copies to family and friends.

The card book and story somehow caught the attention of RKO Pictures producer David Hempstead who showed it to actor Cary Grant’s agent. In April 1944, RKO bought the rights but failed to create a satisfactory script. Grant went on to make “The Bishop’s Wife.”

However, another acclaimed Hollywood heavyweight, Frank Capra, who already had three Best Directing Oscars to his name, liked the idea. RKO was happy to unload the rights. “The story itself is slight, in the sense, it’s short,” Capri said referring to Stern’s book. “But not slight in content.”

Capra bought it and brought in a slew of writers to polish the story. They hired another a well-known actor James Stewart to play the main character renamed George Bailey and in December of 1946, “It’s a Wonderful Life” was released in theaters.

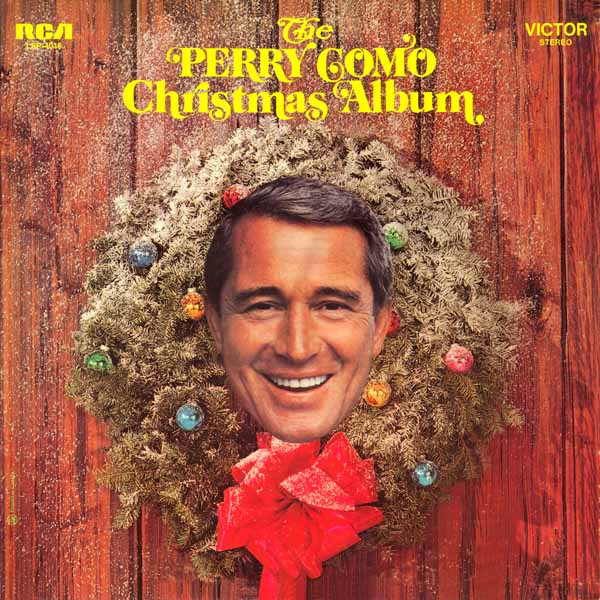

‘Good Guy’ Perry Como was one of the TV Kings of Christmas

By Ken Zurski

Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time. Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television special and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Como’s face and voice became synonymous with the sounds of the season.

That said he may have been the most misunderstood as well.

Como was a one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced his craft incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week. Even Perry was surprised by the remuneration. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the town’s perceived association with mobsters and legalized prostitution, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduce his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually standing backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many wondered how much of it was real. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for 46 consecutive years ending in 1994, seven years before his death in 2001 at the age of 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)

There Is An Artist Behind The Iconic ‘Partridge Family’ Bus

By Ken Zurski

Painter Piet Mondrian, born in 1872, was an important leader in the development of modern abstract art and a major exponent of the Dutch abstract art movement known as De Stijl (“The Style”).

Mondrian used the simplest combinations of straight lines, right angles, primary colors, and black, white, and gray in his paintings.

According to one art historian: “The resulting works possess an extreme formal purity that embodies the artist’s spiritual belief in a harmonious cosmos.”

Mondrian who died in 1944 probably would never have imagined that his well-known artistic style would be the inspiration for a popular 1970’s television show called “The Partridge Family.”

Mondrian’s apparent contribution to the show was the exterior paint job of a school bus used by the fictional – but conventional – family of traveling musicians and singers. Mondrian’s style was on full display, seemingly based on one of his paintings.

The bus became the family’s trademark.

From Yahoo Answers: “Although the exterior paint job was arguably based on Mondrian’s Composizione 1921, it was never explained in the show why this middle class family from Southern California chose Dutch proto-modernism exterior paint, rather than the traditional school bus yellow.”

“The Partridge Family” ran on ABC television from September 25, 1970, until it ended on March 23, 1974. It would find an appreciate and loyal audience in syndication for years. Apparently the bus wasn’t so fortunate. As the story goes, after the show ended, the bus was sold several times until it was found abandoned in a parking lot at Lucy’s Tacos In East Los Angeles.

It was reportedly junked in 1987.

(Some text reprinted from Britannica.com and other internet sources)

Ken Zurski’s book “Unremembered: Tales of the Nearly Famous and the Not Quite Forgotten is available now http://a.co/d/hemqBno

The Year the President Moved Thanksgiving Up a Week

By Ken Zurski

In September of 1939, Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a presidential proclamation to move Thanksgiving one week earlier, to November 23, the fourth Thursday of the month, rather than the traditional last Thursday of the month, where it had been observed since the Civil War.

That year, the last Thursday of November fell on the 30th, the fifth week and final day of the month, and late for the start of the shopping season. The Retail Dry Goods Association, a group that represented merchants who were already reeling from the Great Depression, went to Commerce Secretary Harry Hopkins who went to Roosevelt.

Help the retailers, Hopkins pleaded.

Roosevelt listened. He was trying to fix the economy not break it.

Thanksgiving would be celebrated one week earlier, he announced.

Apparently, the move was within his presidential powers since no precedent on the date was set. Thanksgiving, the day, was not federally mandated and the actual date had been moved before. Many states, however, balked at Roosevelt’s plan. Schools were scheduled off on the original Thanksgiving date and a host of other events like football games, both at the local and college level, would have to be cancelled or moved.

One irate coach threatened to vote “Republican” if Roosevelt interfered with his team’s game. Others at the government level were similarly upset. “Merchants or no merchants, I see no reason for changing it,” chirped an official from the opposing state of Massachusetts.

In contrast, Illinois Governor Henry Horner echoed the sentiments of those who may not have agreed with the president’s switch, but dutifully followed orders.

“I shall issue a formal proclamation fixing the date of Thanksgiving hoping there will be uniformity in the observance of that important day,” he declared, steadfastly in the president’s corner.

Horner was a Democrat and across the country opinions about the change were similarly split down party line: 22 states were for it; 23 against and 3 went with both dates.

In jest, Atlantic City Mayor Thomas Taggart, a Republican, dubbed the early date, “Franksgiving.” Others called it “Roosevelt’s Thanksgiving” or “Roosevelt”s hangover Thanksgiving Day.” More politically, some dubbed it “Democratic Thanksgiving Day” and the following Thursday as “Republican Day.” One observer noted, “This country is so divided it can’t even agree on a day of Thanksgiving.”

In some Midwestern states, especially among farmers, the controversy was irrelevant thanks to a bountiful harvest. “This year the crops certainly justified Thanksgiving, even justified two,” reported the Omaha-World Herald.

Roosevelt made the change official for the succeeding two years ’40 & ’41, since Thursday would fall late in the calendar both times. Then in 1941 The Wall Street Journal released data that showed no change in holiday retail sales when Thanksgiving fell earlier in the month. Roosevelt acknowledged the apparent miscalculation.

However, due to the uproar, later that year, Congress approved a joint resolution making Thanksgiving a federal holiday to be held on the fourth Thursday of the month, regardless of how many weeks were in November.

On December 26, 1941, Roosevelt signed it into law.

The ‘If I Live…’ Promise: A Lusitania Survivor Story

By Ken Zurski

In May of 1915, New York wine importer George A. Kessler was on the deck of the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania watching the crew go through its daily lifeboat drills when he had an idea.

Known as “The Champagne King,” Kessler was sailing to the United Kingdom from New York on business and despite the threat of a German submarine attack in open waters, had no reservations about traveling.

After witnessing the crew drills, however, Kessler went to the captain and asked if there should be drills for the passengers as well. Perhaps, Kessler suggested, each person be assigned a lifeboat, just in case.

The captain graciously said he was not authorized to do such a thing.

Later, hosting a party in his stateroom, Kessler’s concerns were met with indifference. “That is the captain’s decision,” others told him.

Two days later, on May 7, the Lusitania was at the bottom of the sea, befallen by a German torpedo. More than thousand people perished.

Kessler was not one. He survived by reaching a lifeboat. “We tried bailing and balancing, “Kessler recalled, “but the boat would tilt and turn and finally capsized again.”

Kessler made a promise to himself, vowing that if he lived through the ordeal he would help others injured in war.

A promise he would keep.

Later in the hospital recovering, Kessler met a disabled British newspaperman who opened a center for soldiers with eye injuries. Inspired, Kessler sought out a person he knew could help.

Her name was Helen Keller.

Together they founded the Permanent Blind Relief War Fund, an organization which still exists today.

(Sources: Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania by Erik Larsen; Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy by Diana Preston; various internet sites)