Uncategorized

How An Inspired Album Cover Led To An International Phenomenon.

By Ken Zurski

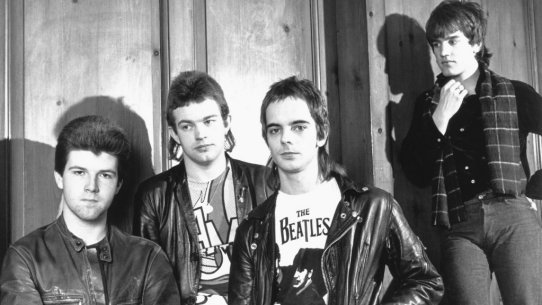

In December of 1981, the English power pop group The Vapors released Magnets, the follow-up to their successful debut album New Clear Days which featured the bouncy and ambiguous hit single, “Turning Japanese.” Although the group had explored dark themes on its first album, Magnets was considered even darker. The title song “Magnets” is about the assassination of the Kennedy’s; “Spiders” and “Can’t Talk Anymore” deal with mental health issues; and “Jimmie Jones,” the single, recounted cult leader Jim Jones and the massacre in Jonestown. Despite the bleak subject matter, however, the songs were mostly upbeat and catchy, a trademark of the group.

The album, while positively received, was a commercial disappointment. The band blamed it on the lack of interest from their new record label, EMI (later changed to Liberty Records), which bought out United Artists shortly after the first release. Due in part to corporate frustration, The Vapors disbanded after Magnets failed to ignite.

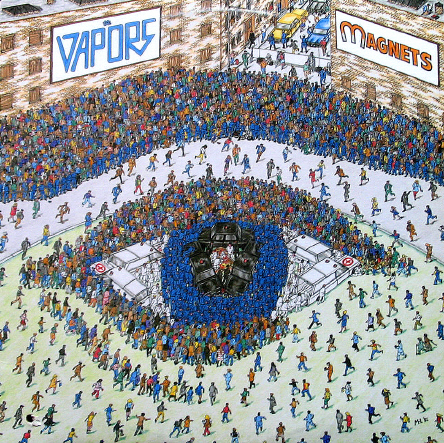

But today, the album has significance for its inspired cover, a complex portrait that mirrored the album’s dark undertones.

Martin Handford was the artist. A London-born illustrator, Handford specialized in drawing large crowds, an inspiration he claims came from playing with toy soldiers as a boy and watching carefully choreographed crowd scenes from old movies.

Handford, who sold insurance to pay bills, was hardly an emerging or successful artist at the time he was asked to design the album cover for Magnets. Drawing upon the theme of the title song, Handford depicted a chaotic crowd scene of an assassination, although you couldn’t tell unless you looked closely. From a reasonable distance, the numerous figures and various colored clothing formed the shape of an eye.

It was both clever and disturbing.

For example, at the top right hand corner of the cover, on the roof of a building, there is a man – presumably the assassin – putting away a rifle. Some of the figures are seen running from the horrific scene unfolding in the “eye’s” iris, while others are curiously drawn to it. Perhaps The Vapors had seen in Handford’s work similarities in their own musical style and themes. The album was an eye-opener, for sure, even before the needle hit the grooves.

But while the cover was certainly an original, the artistic style was not.

In fact it has a name: Wimmelbilderbuch.

Wimmelbilderbuch, or “wimmelbook” for short (German for “teeming picture book”) is the term used to describe a book with full spread drawings of busy place’s like a zoo, farm or town square. The page is filled with numerous humans and animals. It’s geared toward children, but adult’s seemed to like it too, especially when an identified object is hidden, making it more like a puzzle than a colorful picture. Several artists incorporated this style, including a Dutch artist Peter Bruegel, who dates back to the early 16th century, and specialized in drawing intricate landscapes and peasant scenes populated by people in various degrees of distress. Bruegel’s human figures are mostly depicted as frail and challenged.

Handford’s work wasn’t nearly as depressing as Bruegel’s, but they were similar in motive.

Handford purposely drew the Magnets cover with emblematic images, not exactly hidden, but tough to spot, and when found became a personal reward to the viewer – like the tiny assassin on the roof.

This was the inspiration for an idea that eventually became a phenomenon.

Handford came up with a recurring character he would put in all his drawings: a bespectacled man with wavy brown hair who always wore a red and white striped shirt and stocking cap. His name was Wally.

The trick was trying to find Wally in the crowd.

The concept soon became a contest, then a crave. It led to several best selling books and an iconic, some might say exasperating, new enigma emerged.

“Where’s Wally?” is how they describe it around the world.

In America, it’s called “Where’s Waldo?”

Happy Eighth of July? Not Necessarily a Celebration Day for General Washington

By Ken Zurski

On July 8 1776, just days after the Continental Congress passed the Declaration of Independence, a copy was sent to General George Washington who was preparing for battle in New York. Washington was anxiously awaiting word from the assembly in Philadelphia. He knew how important the declaration would be to his troops.

On July 8 1776, just days after the Continental Congress passed the Declaration of Independence, a copy was sent to General George Washington who was preparing for battle in New York. Washington was anxiously awaiting word from the assembly in Philadelphia. He knew how important the declaration would be to his troops.

That’s because up to that point the New York contingent of the Continental Army, who had been together for nearly a full year, hadn’t fired a single shot yet. They were frustrated, antsy and for the most part continually drunk. The declaration would help boost morale, Washington thought.

Certainly talk of such a declaration had been stirring for about a month. In May, George Mason drew up a sentence about being “born equally” with “inherent natural rights,” words later shaped by Thomas Jefferson. And on June 7, Virginian Richard Henry Lee, introduced a congressional resolution declaring that the United Colonies “ought to be free and independent states.” Even Washington , in the spring of that year, crafted a statement that supported the idea of independence as an incentive to fight. “My countrymen, I know, from their form of government and steady attachment therefore to royalty, will come reluctantly into the idea of independency,” he wrote.

So on July 9, at six o clock in evening, Washington ordered his troops to gather. He had previewed the contents of the document and included it in his “General’s Orders,” which would be read aloud to the men.

Washington had warned troops of the consequences that any official documentation of independence would mean if defeated. Treason, he implored, was something the British ruler did not take lightly. Traitors in the past were subject to gruesome disemboweling and beheadings, he explained. Washington himself knew if captured, he would be hanged.

This was literally a fight to the end, he argued.

The men stood with anticipation as the “General’s Orders” were read. Patiently they waited as several mundane paragraphs of typical military reports and directives were announced. One included the procurement of a chaplain assigned to each regiment. “The blessing and protection of Heaven are at all times necessary but especially so in times of public distress and danger,” the missive proclaimed.

Then finally…

“…The Honorable the Continental Congress impelled by the dictates of duty, policy and necessity, having been pleased to dissolve the connection which subsisted between the Country, and Great Britain, and to declare the United Colonies of America, free and independent STATES.”

Upon hearing the words, the men let up “three huzzas” a witness reported. In fact, their enthusiasm led to an act of debauchery that irked Washington. The soldiers marched down Broadway Street and proceeded to topple the large statue of King George III, decapitating it in the process.

Upon hearing the words, the men let up “three huzzas” a witness reported. In fact, their enthusiasm led to an act of debauchery that irked Washington. The soldiers marched down Broadway Street and proceeded to topple the large statue of King George III, decapitating it in the process.

Washington was livid. He told the troops that while their “high spirits” was commendable, their behavior was not. The general wanted an army of orderly respectful men, not savages. Even defacing the likeness of the British King was inadmissible in his eyes.

However sanctimonious that may have sounded, Washington must have been pleased that the statue’s 4 ,000 pounds of gilded lead was melted down to make nearly 43-thousand musket bullets.

Washington was also thrilled by his troop’s eagerness to fight. “They [the British] will have to wade through much blood and slaughter before they can carry out any part of our works,” he wrote about the impending conflict.

Then on July 12, several British ships, including the forty-gun Phoenix, cut through a thin American defense and blasted the city. It was a show of force meant to rattle the colonists into submissiveness. It certainly rattled the nerves of Washington’s untested soldiers who were shaken and distressed by the cries of women and children fleeing the blasts. There was little resistance.

Washington later expressed his disappointment. “A weak curiosity at such a time makes a man look mean and contemptible,” he said chastising the troops.

After the embarrassment, British commander William Howe offered Washington clemency for the rebels if the General surrendered. Washington flatly refused.

The following month, it would get worse. Due to more defeats, the rebels were forced to flee New York to Pennsylvania and reorganize. Later that year, in December, Washington would famously cross the icy Delaware River for a surprise attack in Trenton, New Jersey.

The Revolutionary War would continue for another seven years.

(Sources: Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow; various internet sights)

Betsy Ross? For a Long Time No One Knew. Then Her Grandson Told a Story

By Ken Zurski

In 1752, in Philadelphia on New Year’s Day, Elizabeth Griscom was born to a strict Quaker family who emigrated to the United States from England in the late 17th century. A free spirit in her twenties, Elizabeth ran off and met John Ross an upholsterer’s apprentice and an Episcopalian. Her parents forbade the union outside the Quaker faith, but Elizabeth didn’t care. She married John in a ceremony that took place in a tavern and formally became Elizabeth Ross or “Betsy,” for short.

Today, Betsy Ross is certainly name we recognize.

So much so that in contemporary surveys, many people acknowledge the name Betsy Ross more than interminable historical stalwarts like Benjamin Franklin or Christopher Columbus. However, until her name became synonymous with America’s symbol of freedom, Betsy Ross was a sister, a mother, a widow (three times over), a seamstress, and by the time the rest of the country got to know her – dead for nearly 50 years.

If there was something special about her life, a slice of American folklore, perhaps, she told her family and no one else.

In 1870, however, that would change.

That year, Ross’s last surviving grandson William Canby went before the Historical Society in Philadelphia and told an amazing story about General George Washington, his grandmother and the birth of the American Flag.

According to Canby, Washington had visited Ross’s upholstery shop in Philadelphia with a sketch idea for a unified flag and asked if Betsy could recreate it. “With her usual modesty and self-reliance,” Canby related, “she did not know, but said she could try.”

Canby says among other revisions, Betsy suggested that the stars be five-pointed rather than six as Washington had proposed (Washington thought the six-pointed star would be easier to replicate). The story was as revealing as it was skeptical. No one had heard of Betsy Ross and previous stories of the first flag was apocryphal at best. There were many nonbelievers and even today historians have doubts. There are no records to support Canby’s claim, they insist, even though Canby had signed affidavits to back up his story.

At the time of Washington’s proposed visit in 1777, Ross would have been in her 20’s. Her life was typical for a young women at the time. She endured two marriages that ended tragically (her first and second husband’s death were both attributed to war.) A third marriage produced five children. She passed away in 1836 at the age of 84. There is no documentation that she publicly promoted her own role in making of the flag – or was even asked. Apparently only her family knew.

Nearly a century later, however, in the midst of the Reconstruction period, a changing nation embraced Canby’s story of his grandmother and Ross became the face of America’s first flag. The early flag became affectionately known as “The Betsy Ross Flag,” and trinkets of the thirteen stars and stripes were a big seller.

Even hardened critics, who claim many seamstresses may have played a role in the flag’s creation are willing to concede, for history’s sake at least, that one name gets credit for the five-pointed stars.

Betsy Ross.

Henry Ford, the Vagabonds, E.G. Kingsford, and the History of the Charcoal Briquette

By Ken Zurski

In 1919, car-making giant Henry Ford had been eyeing a significant tract of land on the far western portion of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan known as Iron Mountain. Ford’s cousin, Minnie, to whom he was very close, lived there along with her husband E.G. Kingsford who ran a successful timber business and owned several car dealerships thanks to his wife’s family connections.

Ford had begun wrestling control from his stockholders and purchasing raw materials to be used in making his vehicles. Anything to make his car making process more efficient. Kingsford had a beat on something Ford desperately sought. So Ford invited Kingsford to go camping with him. To talk business, he explained.

At the time, Ford had been making headlines across the country, not just for making cars, but for actually using one. Ford went on road trips. The press dubbed it, “auto-camping,” because Ford along with his three close friends, who called themselves “the vagabonds” would travel by automobile during the day then set camps at night..

Ford’s camping companions were no slouches. They included Harvey Firestone, the tire company founder; John Burroughs, the conservationist; and inventor Thomas Edison. Their journeys included a jaunt through the Florida Everglades and treks across mountainous regions in West Virginia and New England. Their first trip to the Adirondacks in 1918 was so satisfying they all agreed to make a trip to new destinations every year.

The trips were well-organized, well-stocked and oftentimes well-staffed with cooks and a cleaning crew. Like true campers, though, the formidable men did sleep on folding cots in a ten-by ten canvas tent. Burroughs, in his 80’s and the oldest of the four (Ford was in his 50’s), chronicled most of the adventures. He marveled at their resiliency. “Mr Ford seizes an ax and swings it vigorously til there is enough wood for the campfire,” he wrote.

Each year newspapers ran features of the “vagabonds” latest adventure and newsreels were shown in movie theaters throughout the country. After all these were prominent American inventors and “heroes” to some like Edison and Ford, who despite their gray hair, and unabashed preference to wear business attire – tight collars, three piece suits and ties – even on the retreats, were “roughing it,” so to speak, in the great outdoors.

The papers couldn’t hide the obvious irony of it all. “Millions of Dollars Worth of Brains Off on Vacation,” the headlines blared. Even President Harding joined the men briefly for one excursion.

Burroughs diary accounts however, especially the campfire chats, would be interpreted much differently today. “Mr. Ford attributes all evil to the Jews or the Jewish capitalists,” Burroughs wrote in his diary about one particularly spirited late night conversation. Ford’s antisemitism would surface later, but at the time, the prejudice against Jews was not as divisive as it is today.

But no such controversy followed the “vagabonds”in the papers. “Genius to Sleep Under the Stars,” read one article followed by tales of playful tree climbing, stream wading and bird watching. “The four famous men were like so many little boys,” a Ford biographer wrote,”…the white-haired Huckleberry Finns.”

Kingsford must have been pleased and a little flattered by Ford’s invitation to join “the vagabonds” in Green Island, New York, a popular fishing spot near Edison’s Machine Works company in Schenectady.

Ford had a purpose. He needed land. Specifically, he needed land with timber on it. Nearly one-million board feet a day was used to manufacture the popular Model T’s, whose chassis were made mostly of wood.

Kingsford convinced Ford to buy some flat land near the Menominee River and build a wood distillation plant. Ford heeded his advice and went even further. He would build the plant and an electric dam nearby to power it.

Ford hated to waste anything and in the wood distillation process there was always a lot of waste, specifically wood chip ash, or rough charcoal. So Ford had an idea. He mixed the crushed charcoal with a potato starch glue and pressed the blackened goo into a pillow-shaped briquette. When lit, it burned white ash and produced searing heat, but little or no flame.

Ford was not the first person to come up with the idea of charcoal in a briquette. That honor goes to a man named Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer from Philadelphia who patented the idea in 1897. Ford, however, was the first to commercially market it.

Ford was not the first person to come up with the idea of charcoal in a briquette. That honor goes to a man named Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer from Philadelphia who patented the idea in 1897. Ford, however, was the first to commercially market it.

He advertised the new product as “a fuel of a hundred uses” and perfect for “barbecues, picnics, hotels. restaurants, ships, clubs, homes, railroads, trucks, foundries, tinsmiths, meat smoking, and tobacco curing.”

For home use, it was less dangerous than a traditional wood fire, but just as useful. “Briquette fire alone is enough to take the chill off a room,” the instructions informed. “Absence of sparks eliminates this menace to rugs, floors and clothing.”

Ford’s put his signature logo on the charcoal briquettes bags and sold them exclusively at his many car dealerships. When Ford died in 1947, the charcoal business was phased out. Henry Ford II took over and sold the chemical operation to local business men who changed the name to reflect its local heritage: Kingsford Chemical Company.

Ford’s put his signature logo on the charcoal briquettes bags and sold them exclusively at his many car dealerships. When Ford died in 1947, the charcoal business was phased out. Henry Ford II took over and sold the chemical operation to local business men who changed the name to reflect its local heritage: Kingsford Chemical Company.

By that time, Kingsford was not just a person, but a city. Thanks to the economical success of Ford’s wood, parts and charcoal plant, the land used to build the original timber business was named in honor of its first industrialist.

His story is rarely told.

(Pardon, if it reads like a resume, but details are sparse.)

Born in Woodstock, Ontario, Edward George Kingsford moved to Michigan as a young boy. He lived on his parents farm in Fremont before becoming a timber agent and moving to Marquette in the Upper Peninsula. In 1892, Kingsford married Mary Francis “Minnie” Flaherty, Henry Ford’s cousin. Several years later, Kingsford signed a contract to become a Ford sales agent in Marquette and eventually moved to Iron Mountain where he bought tracts of land for timber and opened several Ford dealerships. When Ford called to discuss the possibility of using the massive timber resource for his car making, Kingsford answered. Eventually, the once uncharted land, about five square miles total, was named Kingsford, Michigan.

Despite the distinction, however, Ford, not Kingsford, is prominently associated with the town’s history. Ford was responsible for putting up the large factory, employing hundreds of workers, and building modern houses for the workers and their families to live. Within just one year, in 1920, the population of Kingsford blossomed from a mere 40 residents to nearly 3,000, creating a town out of an enterprise, thanks to Henry Ford.

By the time Ford’s imprint left in 1950, Kingsford the town was established enough to persevere, although the plant’s closing was a blow economically. After the parts plant shuttered the charcoal business also left; moving operations to Louisville, Kentucky in the 60’s.

Ford’s name is still displayed on several establishments in town: Ford Airport, Ford Hospital and Ford Park are just a few examples. In a a publication honoring the city’s 75th Jubilee, Kingsford is refereed to as “The Town that Ford Built.”

Some might say that’s a slight to Kingsford, the man, who by association convinced Ford to venture out to the remote section of the Upper Peninsula, ultimately invest in some land, and put a little city on the map.

Today, you have to go to Kingsford, Michigan to get the full story.

You’ll see. Ford gets the credit.

But when it comes to charcoal, we all know whose name is on the bag.

(Sources: I Invented the Modern Age : The Rise of Henry Ford by Richard Snow; Ford: The Men and the Machine by Robert Lacey; various internet sites)

Amy Johnson, Britain’s Queen of the Air

By Ken Zurski

Amy Johnson is considered the English version of American Amelia Earhart which is a fair comparison since both pioneer aviators have similar adventures and equally mysterious fates.

Johnson, however, is not quite as well known.

Born in Yorkshire, Johnson earned an economic degree at the University of Sheffield and received her pilot’s license through the London Aeroplane Club in July of 1929. Flying was just a hobby for the 26-year-old Johnson at first. But that would change. “I have an immense belief in the future of flying”, she wrote. Soon enough she had her sights on breaking solo flying records in Europe, similar to what Charles Lindbergh and Earhart were doing in the States.

Her father and biggest supporter, Lord Charles Wakefield helped finance her flights. The wealthy Wakefield, a well-known figure in London, founded an oil lubricant company that bared his name (later it was changed to Castrol Oil). Wakefield bought Johnson her planes which carried family trademark nicknames, like “Jason.”

In May of 1930, aboard “Jason,” Johnson set off alone from Croydon, England and 19 days later landed in Darwin, Australia a distance of 11,000 miles. She was given a hero’s welcome upon returning home.

Later along with several co-pilot’s, including her husband Scottish aviator Jim Mollison, Johnson completed more globetrotting flights and set distance records from London to Moscow and Japan. Accomplishments that received international recognition. Even Lindbergh, the most famous pilot in the world, sent Johnson a letter of praise.

Later along with several co-pilot’s, including her husband Scottish aviator Jim Mollison, Johnson completed more globetrotting flights and set distance records from London to Moscow and Japan. Accomplishments that received international recognition. Even Lindbergh, the most famous pilot in the world, sent Johnson a letter of praise.

In 1941 while working for the Royal Air Force, Johnson was lost during a flight over the Thames Esturay where the River Thames meets the North Sea. The weather was especially bad that day and she reportedly went off course, ran out of fuel, and ditched the plane.

Johnson was last spotted parachuting into the water.

Even today, her fate is debated and rumors circulate about why the plane went down. Some claim Johnson forgot – or failed – to give the correct security codes needed to identify herself as a British pilot and was shot down by friendly fire. Others report she and her aircraft was mistaken for a German bomber. Still others believe she may have been on a secret government mission. All speculation, of course.

Like Earhart, who vanished in 1937 while flying over the Pacific, Johnson, who was assumed drowned, never resurfaced.

A search for her body turned up nothing.

Elbridge Gerry, the Blue Bottle Fly, and the Shaping of the Constitution

By Ken Zurski

Massachusetts statesman Elbridge Gerry was of the cantankerous and crafty sort. He typically came late to engagements and was usually the first to tell the host that he had finally arrived. This is the mark he made on the Constitutional Convention in May of 1787 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia during the drafting of the nation’s first constitution.

Actually he made no physical mark on the Constitution, refusing to sign the document and disagreeing with most of the other 40-plus delegates on how much power to give the government in relation to its people. Gerry had signed the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation, but the Constitution was different. There were too many variables and not enough unity, he argued. “If we do not come to some agreement among ourselves. “Gerry maintained, “some foreign sword will probably do it for us.”

In September, after the final draft of the Constitution was reached, Gerry along with two others, Edmund Randolph and George Mason, all agreed the document needed to protect the rights of people of whom whose basic freedoms should be added. Freedoms similar to the one Mason, the governor of Virginia, had drafted in his home state.

Therefore, they argued, it was incomplete.

Mason urged the framers, now drafters, to stay on as long as needed to finish the task. Gerry seconded the motion. The answer from all the other delegates, however, was a resounding, “No.”

Whether or not any of the other participants agreed such rights were necessary wasn’t the point. Most had been away from their wives and families for months and were ready to leave. In addition, they were weakened by the heat and humidity and disgusted by the cramped sleeping quarters of two to four men per room which during a severe infestation of the blue bottle fly kept the windows shut and the smells in.

Frankly, they were just plain sick of fly’s, the heat, and each other.

Many nearly walked out a month before in August, but trudged on to complete the task. But staying longer? That was not an option for those who actually signed the document. They went home.

Several years later, James Madison’s proposal of twelve amendments was approved by Congress.

It was appropriately titled the Bill of Rights.

Australia’s Rabbit Fence And The Man Responsible For It Being Built

By Ken Zurski

Thomas Austin likely had no idea he alone would be blamed for the massive jackrabbit infestation in Australia which grew so expeditiously that it reached epidemic proportions in the late 1800’s. Austin was an avid hunter and was looking for something, anything, to hunt. Rabbits seemed an obvious choice to an Englishman, but they weren’t native to Australia. So someone had to bring them in. That someone was Thomas Austin.

Today, a long fence from the top of the country to the bottom still stands as a testament to his poor judgment.

Here’s the story.

Born in Somerset, England, Austin a sheep farmer, came to Australia’s Western District of Victoria in 1831. At the time Australia was not unified country but an island made up of five British Colonies. Austin may have been asked to come and help establish the agriculture and livestock footing in the region. He built a retreat of nearly 30-thousand acres called Barwon Park and became a distinguished member of the Acclimatization Society of Victoria, which introduced new animals and plants to the colony. Austin liked birds, so he brought in blackbirds and partridges. His grazing land was used mainly for sheep and horses.

Austin, who was wealthy and socially connected in his native land, liked to hunt and often hosted lavish shooting parties. But there was a problem. Unlike in England where hunting was a sporting good time, in Australia, there was nothing in significant numbers to aim at. So he had an idea. Bring me some rabbits, he ordered.

In 1859, a ship called Lightning on consignments brought 24 wild rabbits to Austin for breeding. Austin let a few go in hopes of hunting their offspring. “The introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home,” he said at the time.

He had no idea.

The locals clearly stood by Austin. A little sport couldn’t hurt the neighborhood, in fact it might actually help the economy, they thought.“We hope that the common interest will be felt in saving them from being destroyed until they have so far increased to render shooting of one of them now and then as a matter of trifling importance,” an editor of the Southern Australian opined.

Austin’s plan worked perfectly.

In 1867, Queen Victoria’a second son Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, came to visit and stayed at the Austin ranch. Together the two men spent the day hunting and in just over three hours had shot and killed nearly 1000 rabbits. The Duke got nearly half of the kills and was so pleased that he came back for more the following year with even better results: more than 1500 rabbits down. The local press was quick to point out the obvious absurdity of it all. “In such an indiscriminate slaughter,” they reported, “ we cannot see how any precise conclusion can be arrived at.” Already the apparent growth of the bunny population was getting notice.

But the hunting was glorious.

Austin however was embarrassed that he could only offer the Duke modest accommodations at his ranch and certainly nothing befitting royalty. The slight, in Austin’s mind, gnawed at his English pride. So after the Duke left, Austin began construction of a larger home, a lavish 42-room mansion in hopes of having more royal visits and more successful hunting parties. The Barwon mansion as it is called today was completed in 1871. Six months later, Austin was dead at the age of 54. His widow, Elizabeth ,and most of their 11 children stayed at the mansion for many years. The hunting parties stopped, but the rabbits did not.

They would become Thomas Austin’s legacy.

Well, that and the fence.

But first lets backtrack a bit to May of 1787. That’s when 11 ships sailed from Great Britain and landed at Port Jackson, Australia, an area already explored and claimed by Captain James Cook nearly two decades before. The ship was loaded with a large crew and hundreds of “convicts” whose sentences were years of “transportation,” or in effect deportation. Until 1776, they were deposited in the thirteen American colonies, but since the colonies were now free of British rule, the new Americans understandably didn’t want them. The convicts, mostly petty thief’s, including women and children, would serve their sentences on unspoiled land, working to establish a new colony, or penal colony, in this case. But first they had to survive the harsh conditions of the journey. Stuck in cramped quarters below deck, with closed hatches, and filled with rats, parasites and other maladies, dozens either died or were sickened. The crew had no morals either. Women were raped and many were kept without food and water as punishment. Land was a welcome sight.

On January, 26 1788, now known as Australia Day, a new British settlement was born on the island. Among the new residents were several caged rabbits (reports are there were five) who were brought along for reasons unclear. Later a dispute between two colonists over their ownership was reported. But not much else is known of the rabbits fate. Likely they became someone’s dinner. But it is worth noting in regards to this story, that it was the first time rabbits were introduced to Australian soil, but only a few.

More stories of rabbit-farming enclosures in Australia appeared after that, but nothing more than controlled breeding. Basically rabbits were bred to be eaten, like chickens or turkeys are today.

That is until Austin was looking for something to hunt.

By 1864, while Austin was still alive, complaints started coming in from farmers throughout the region. Their crops were being overrun and decimated by the bushy tailed critters. Although the jackrabbits certainly weren’t native to the land, the land was perfect for them to thrive. Winters were mild and ideal for year round breeding and widespread farming on the rich soil meant they always had something to eat. Bunny families quickly grew in very large numbers until they were not only destroying crops but plant species as well. Young trees in orchards were felled by “ringbarking,” a process by which an animal strips away a portion of the bark completely around the tree. also known as girdling. Girdling eventually kills the tree.

Austin must have known about this, but was powerless to stop it. He could only kill so many.

In 1864, government officials stepped in and offered a substantial reward for “any method of success not previously known in the Colony for the effectual extermination of rabbits”. More than a thousand suggestions were received. Many were deemed unsafe, but that didn’t stop the use of poisons and other widespread killing methods including one called “ripping” where sharp tillers were dragged along the ground dismembering the rabbits in their burrows and effectively destroying and burying them at the same time. Other animals like ferrets and cats were used, but to little impact. And besides, no one wanted more cats. (The feral cat population was actually a problem like the rabbits in Australia, but on a much smaller scale).

Finally in 1901, the idea of building a wall was raised and quickly approved by the Colonel Government. But a wall in a practical sense was a bit of an exaggeration. Typically a wall to keep large predators – or people – out is built high, sturdy and solid. But in this case the offender was only five inches tall. So, in essence, the “wall” would be more like a fence and similar to one you would put up in your garden for the same purpose – only straighter and much longer. The fence was planned at a little over three feet in height and made mostly of wood or iron; then covered in barbed wire and wire netting. The bottom would sit six inches below the surface.

The fence would extend from new South Wales to Southern Australia a distance of about 346 miles, effectively creating a border along the northern mid-territories. The fence’s objective was to keep the rabbits from spreading into the western territories. A rabbit plague across the entire land mass would be irreversible and devastating. If anything, the makeshift “wall” would contain the rabbits in an area where exterminating them was somewhat more feasible. Two more fences would be be built extending the length to nearly 1500 miles total.

It was a massive undertaking and would take nearly seven years before all three proposed sections were completed. In the southern regions, known as the Great Victoria Desert, camels were used to pull carts and transport material since they could survive the heat and go for days without water, a scarcity in the outback.

It was a massive undertaking and would take nearly seven years before all three proposed sections were completed. In the southern regions, known as the Great Victoria Desert, camels were used to pull carts and transport material since they could survive the heat and go for days without water, a scarcity in the outback.

The fence had limited success. Rabbits were wily creatures who found ways to breach it. Some were agile enough to simply jump over it. Still for a time, population was being controlled at least in some respect by slowing the rabbits down at the fence border and rounding them up for mass killings. But there were still millions more left. In 1898, it was reported to be nearly 300-million. By comparison, the human population in all of Australia at the time was 3-million.

Across the world, and especially in the U.S., Australia’s rabbit dilemma was treated seriously, but also with a humorous tone. “Br’er rabbit is a terrible pest in Australia” the Chicago Daily Tribune reported in April 1901, tying the article into the upcoming Easter holiday and a cutesy tale about Mollie Cottontail, Br’er’s wife in the Uncle Remus stories, who is “responsible for all the [Easter] eggs.”

The situation in Australia was dire enough, however, to warrant several paragraphs of startling comparisons and anecdotes. “Geniuses who love to calculate, have figured out that the tails of the 25,000,000 [yes, that’s 25 million!] rabbits killed in a year in Australia if sewn together would girdle the earth [a reference to girdling, no doubt].” Hunting them down, the article goes on to report, had been as successful as “drying up the ocean by dipping the water out a spoonful at a time.”

Austin was not mentioned in any coverage at the time. Only later would his name become synonymous with the bunny epidemic.

Too bad really because after Austin’s death , Elizabeth, his widow used her husband’s money to open up a hospital for incurable diseases in Heidelberg, a suburb of Melbourne. She also founded the Austin Home for Women, in Geelong, a port along the Barwon River, and Victoria’s second largest city by population.

Elizabeth died in 1910. In her obituary, she was lauded for her philanthropic contributions. “Since the incorporation of the institution in January of 1882, it has won for its benefactress the affection and gratitude of hundreds of unfortunate incurables who were denied admission to the general infirmaries.”

For her efforts, Elizabeth should be the Austin best remembered in Australia today.

Instead her husband, Thomas, the hunter, for completely different reasons, gets the nod.

After all, he released the bunnies.

Clean Up Please: The Struggle To Get Everyone To Take A Bath

By Ken Zurski

In 1902, psychologist and chemist, William Thomas Sedgwick released a book titled Principles of Sanitary Science and Public Heath which was a compilation of lectures he gave as a professor of biological sciences at MIT.

In it, Sedgwick extolled the virtues of good personal hygiene to keep infectious diseases away. “The absence of dirt,” he urged with conviction, “is not merely an aesthetic adornment.”

Basically, he was telling everyone to take a bath.

Sedgwick was onto something. Until then bathing in particular was an option most people chose to ignore. That’s because for centuries, cleanliness was seen as a sign of weakness or impurity. In some ancient religious philosophy’s, being wet, or letting the water touch you, was akin to allowing the devil enter your body. And in other circles, bathing was considered a sign of sexual mischievousness. Queen Isabella of Castile bragged that she took a bath only twice in her life, on her birth day and her wedding night. And Saint Benedict, an English monk who lived a solitary and monastic life, said “bathing shall seldom be permitted.” Of course that was a long time ago when attitudes were based on god fearing principles, not logic. But even at the turn of the 20th century, personal hygiene was still somewhat taboo.

Sedgwick of course wasn’t the first to encourage others to get well by getting clean. Benjamin Franklin, a man of many titles, was also an early advocate of good hygiene habits.

Sedgwick of course wasn’t the first to encourage others to get well by getting clean. Benjamin Franklin, a man of many titles, was also an early advocate of good hygiene habits.

As America’s first diplomat in France, Franklin thoroughly enjoyed the pleasures of taking a bath, a European luxury, although his desires may have been influenced more by the pretty French maids who administered it. “I have never remembered to have seen my grandfather in better health,” William Temple Franklin wrote to a relative. “The warm bath three times a week have made quite a young man out of him [Franklin was in his 70’s at the time]. His pleasing gaiety makes everybody love him, especially the ladies, who permit him always to kiss him.”

Despite this, Franklin couldn’t help but get clean, right?

However, when a large tub of warm water wasn’t present, Franklin liked to take what he called “air baths.” Franklin thought being inside and cooped up in a germ infested, walled, and shuttered space, was the reason he got colds. So to keep from getting sick, Franklin would open the windows and stand completely naked in front of it. Ventilation was the key to prevention, he explained, although others likely weren’t so emboldened.

In the mid 19th century, bathtubs were heavy and costly and those who could afford it used it as much for decoration as for its intended purpose.

Before indoor plumbing, a large tub may have been made of sheet lead and anchored in a box the size of a coffin. Later bathtubs became more portable. Some were made of canvas and folded; others were hidden away and pulled down like a Murphy Bed. They were called “bath saucers.”

It wasn’t that most people didn’t understand the merits of taking a bath, but it was a chore. Water had to be warmed and transported and would chill quickly; then dumped. Oftentimes families would use the same bath water in a pecking order that surely forced the last in line to take a much quicker dip than the first.

In the later half of the 19th century, as running water became more common, bathtubs became less mobile. Most were still bulky, steel cased and rimmed in cherry or oak, but stationary. Fancy bronzed iron legs held the tub above the floor.

In the later half of the 19th century, as running water became more common, bathtubs became less mobile. Most were still bulky, steel cased and rimmed in cherry or oak, but stationary. Fancy bronzed iron legs held the tub above the floor.

Ads from the time encouraged consumers to think of the tub as something other than just a cleaning vessel. “Why shouldn’t the bathtub be part of the architecture of the house?” the ads asked. After all, if there is going to be such a large object in the home, it might as well be aesthetically pleasing.

Getting people to actually use it, however, that was another matter.

Sedgwick had medical reasons to back up his claims. As an epidemiologist, he studied diseases caused by poor drinking water and inferior sanitation practices. Good scientific research, he implied, should be all the proof needed. But attitudes and decades old habits needed to change too. “It follows as a matter of principle,” Sedgwick wrote, “that personal cleanliness is more important than public cleanliness.” He had a point. Largely populated cities were dirty messes, full of billowing black smoke from factories, coal dust, and discarded garbage and waste. Affixing blame for such conditions was more popular than actually doing something about it. Sedgwick focused on self-awareness to make his point. “A clean body is more important than a clean street,” he stressed.”Sanitation alone cannot hope to effect these changes. They must come from scientific hygiene carefully applied throughout long generations.”

People, it seemed, had to literally be scared into taking a bath.

Something Sedgwick understood, but fought to amend.

“Cleanness,” he wrote in his book, ”was an acquired taste.”

Mark Twain, Nikola Tesla and the “Irregular” Solution

By Ken Zurski

Around the same time Nikola Tesla was making waves in America for inventing an alternating current (AC) electrical power source and engaging in a “War of Currents” with his former employer and now adversary Thomas Edison, one of the Serbian-born scientist and engineer’s lesser known laboratory experiments took an unexpected and unusual turn.

It was in the 1890’s and Tesla had perfected what he called the Oscillator, or an AC generator that introduced a reciprocating piston rather than the standard rotating coils to generate power. Tesla used steam to drive the piston back and forth and a shaft connected to the piston moved the coils through the magnetic field. The result was higher frequencies and more current than conventional generators.

He patented this machine and unveiled it to great curiosity at the Chicago World’s Fair. “Mr. Tesla has taken what may be called the core of a steam engine and the core of an electrical dynamo, given them a harmonious mechanical adjustment, and has produced a machine which has in it the potentiality of reducing to the rank of old metal half the machinery at present moving on the face of the globe,” the New York Times raved.

Proving the “mad scientist” was never satisfied with his own work and always tried to improve what he had already achieved, when Tesla returned to his New York lab he attempted to use compressed air instead of steam. He built this on a platform that vibrated at a high rate, driving the piston when the column of air was compressed and then released. Even though it didn’t generate enough electricity to power a lighting system, Telsa was amused nonetheless, especially when he stood on the platform. “The sensation experienced was as strange as agreeable,” he wrote, “and I asked my assistants to try. They did so and were mystified and pleased like myself.”

Only one problem. Each time Tesla or one of his assistants stepped off the platform, they had to run to the toilet room. The reason was obvious, especially to Tesla. “A stupendous truth dawned upon me. Some of us, who had stayed longer on the platform, felt an unspeakable and pressing becessity which had promptly been satisfied.”

Basically, they had a sudden urge to empty their bowels.

Intrigued, Tesla kept experimenting and ordering his assistants to “eat meals quickly” and “rush back to the lab.” Tesla may have failed in an attempt to upgrade his own machine, he thought, but succeeded in the prospect at least of using electricity to cure a number of digestive issues.

But to be sure, he unsuspectingly enlisted the help of a friend.

Mark Twain and Tesla were seemingly unlikely acquaintances. In addition to his writing, Twain was a failed inventor, or at least a failed backer of inventions, like the automatic typesetting machine which he poured thousands of dollars into and even more into finding a workable electric motor to power it. Unsuccessful, Twain read about Tesla’s AC steam-powered motor generator and gushed at its simplicity and ingenuity. “It is the most valuable patent since the telephone,” Twain wrote without a hint of his usual sarcasm.

Tesla had sold his invention to lamp maker George Westinghouse’s company which also impressed Twain who lost a sizable portion of his own fortune on the typesetter machine. So at some point the two men met and Twain visited Tesla’s lab. The result is a famous photograph of Twain in the foreground acting as a human conductor of electricity as Tesla or an assistant looms mysteriously in the background. But Tesla fondly remembers helping his friend too. “[Twain] came to the lab in the worst shape,” Tesla recalls, “suffering from a variety of depressing and dangerous elements.”

As the story goes, Twain stepped on the vibrating platform as Tesla had suggested. After a few minutes, Tesla begged him to come down. “Not by a jugfull,” insisted Twain, apparently enjoying himself. When Tesla finally turned the machine off, Twain lurched forward looked at Tesla and pleadingly yelled: “Where is it?”

He was, of course, asking for direction to the toilet room. “Right over there,” Tesla responded chuckling. But Tesla knew he had done Twain a favor. “In less than two months, he regained his old vigor and ability of enjoying life to the fullest extent.”

Of course, Tesla never did patent or market a machine for such a specific purpose and Twain didn’t talk about it, so it’s mostly lost to time, unlike the photograph. Both men now have an important place in history and numerous books are written about them. Twain’s recollections are mostly in his own hand. But the story of Twain’s visit to Tesla’s lab and Twain’s resulting step on the oscillating platform is found in Tesla’s versions, not Twain’s.

Perhaps, as one Tesla biographer suggests, it was all a big practical joke, which certainly – and quite remarkably – turns the tables on both men’s reputations considering Twain was the humorist and Tesla the brain.

Despite this, and knowing the outcome, even if it was only intended for a laugh, both men were likely pleased with the results.

But for completely different reasons.

How An Insane Asylum May Have Inspired the Iconic Twin Spires of Churchill Downs

By Ken Zurski

In 1794 a man named Isaac Hite, a Virginia Militia Officer, came to the Kentucky frontier with other surveyors to stake claim on scenic tracts of land given to them for fighting in the French and Indian War. They founded the properties as promised, but also encountered more Indians. And so in his newly adopted home now known as Anchorage, just outside of Louisville, Hite was killed by the hostile natives.

Or was he?

The introduction of a book containing Hite’s personal journal disputes claims he was struck down, but rather died from “natural causes,” at the age of 41. His companions, the book asserts, “had died years before, and violently, while taking Kentucky and holding it against the Indians.” One theory is that Hite was injured by Indians and later died from his wounds. But how he died isn’t as important as what he left behind. A parcel of land where he settled, started a family, and ran a mill and tannery.

Through the years, and for many generations, Hite’s descendants tended the land known as Fountain Bleu and an estate they dubbed Cave Springs Plantation. Then in 1869, the family sold the parcel to the State of Kentucky. The reason the state wanted it was explicit: open a new government institution for troubled youths near its largest city.

The rural, secluded site of Hite’s Cave Springs was the perfect setting for such a facility. Originally known as the “Home for Delinquents at Lakeland,” it was named after the path that led to it’s front gate, Lakeland Drive. It was converted – or just transformed – into a mental hospital in 1900 and renamed to reflect the often misunderstood and misdiagnosed residents who inhabited its 192 beds. “The Central Kentucky Lunatic Asylum,” as it was now called, became the state’s fourth facility for such a purpose.

As with any institution for the mentally challenged, in the early 20th century, the day-to-day operations were marred by allegations of abuse, malfeasance and deaths. Massive overcrowding was reported in the mid 1900’s and in 1943 the state grand jury found the asylum was committing people that were neither insane nor psychotic. One man was reportedly admitted for simply spitting in a courtroom. While the scientific merits of electric shock therapy and lobotomies were morally judged, the reports of fires, murders, and multiple escapes at the facility consistently filled the newspapers. It was a horror show.

Since many died on the grounds, many were buried there too. So stories of ghosts and haunted spirits are attributed to the site. “Have the mournful souls that died at Central State remained at the only home most of them ever knew?” a local ghost hunter asked.

The grounds, however, are also tied to the storied history of the Louisville underground. Literally, a series of caves and tunnels used before prohibition to move shipments – perhaps contraband during the Civil War – from the river docks to downtown buildings. Since a small cave existed before a tunnel was added, Hite was probably the first to discover the hole through the rock on his newly claimed property. Later after the state took over, the cave was reinforced with brick walls and pillars and used as cold storage mostly for perishable items like large cans of sauerkraut. The inside was reportedly lined with so many sauerkraut cans it was given a name by the locals: Sauerkraut Cave.

In the back of the cave a tunnel was built which has its own back door, so there was a natural entryway and a man made exit. Many morose stories about the lunatic asylum involve Sauerkraut Cave, including tales of residents who may have used it as an escape route or more graphic reports of pregnant patients who went there to give birth and abandon their babies. Those who visit the site today say without lights the cave would have been too dark and too flooded to navigate. Still, desperate patients may have drowned or froze to death trying.

Regardless of how many people perished on site or off, the general scientific worth of the experiments, and the ghastly stories that followed, the building itself was considered a architectural wonder at the time it was built.

Looking like a medieval castle in the front, the three story structure with wing additions on each side was made of solid red brick with stone trim. The small pane windows in the main building had segmental arches with brick molding and the facade was highlighted by a columned porch and railing. On the side of the main building is two identical towers, shooting high into the air and inspired by the Tudor revival style used in its original design. It quickly became one of the Louisville area’s most distinctive and important buildings when it opened its doors in 1869. By the time it came down, in the late 20th century, it had represented something else entirely.

But it’s legacy may be more lasting than you think.

Enter Joseph Dominic Baldez.

Baldez wasn’t even born yet when the asylum building was built, but eventually worked for the firm that created it. D.X Murphy & Bros was an offshoot of another firm established by Harry Whitestone. In the 1850’s. Whitestone, an Irish immigrant, designed some of the city’s elaborate homes, hotels and hospitals, including the Home for Delinquents on Lakeland Drive. When Whitestone retired in 1881, his top assistant Dennis Xavier (D.X.) Murphy took over the business. Baldez began working for Murphy at the age 20.

In 1894, Baldez, a native of Louisville and a a self-effacing, self-taught draftsman, started work on a project at the area’s racetrack known as Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby, the prestigious race for three-year-old thoroughbreds held every year at the beginning of May.

For 20 years since the track was built, the seating had been on the backstretch, facing west, a mistake, since the late afternoon sun would be directly in spectators eyes. So a new larger structure was planned on the other side, facing east, or directly near the one-eighth pole on the stretch. The D.X. Murphy firm was hired and the young Baldez, at 24, was commissioned to design the new stands. He went to work constructing a 250-foot long slanted seating area of vitrified brick, steel and stone with a back entrance wall lobby which on its own was not only fancy and stylish, but efficient too. It was graciously received: “The new grandstand is simply a thing of beauty,” raved the Louisville Commercial. The new grandstand included a “separate ladies section” and “toilet rooms,” the paper noted.

The Courier-Journal also chimed in: “With its monogram, keystone and other ornate architecture, it will compare favorably with any of the most pretentious office buildings or business structures on the prominent thoroughfares.”

Then there are the candles on the birthday cake, so to speak.

The Twin Spires.

Whether Baldez was asked to include it, or came up with the idea on his own is unclear. His diagrams clearly show what he intended to do: put one large spire on either side of the grandstand for ornamental decoration. Each spire would be 12 feet wide, 55 feet tall, and sit 134 feet apart from center to center. The base shape was octagonal for strength and surrounded by eight rounded windows which were designed to stay open (although later were glassed over to keep birds out). Above the windows was a decorative Feur-de-lis, or a “flower lily” shape, flanked by two roses which were decorative rather than symbolic since the race didn’t become the “Run for the Roses” until the late 20th Century.

Although others, like the track president at the time Col. Matt J. Winn, greatly admired the spires, Baldez was indifferent about his work. “They aren’t any architectural triumph,” he argued. “But are nicely proportioned.”

Although no one can be absolutely certain, and little about Baldez is known other than his designs, the building which housed the mental patients on Lakeland Drive on the former property of one of its first residents may have sparked the idea for the Twin Spires at Churchill Downs. The comparisons are justifiable. Both have large steeples, two in fact, and the tops of each are similar in design. Plus, Baldez knew the asylum building well by working at the firm that built it.

Perhaps as some suggest, the name Churchill Downs was also an inspiration for Baldez’s “steeples.” Churchill, however, was not a religious connotation, but the surname of the original owners John and Henry Churchill who leased the land to their cousin Colonel Meriwether Lewis Clark who subsequently built the track on the property.

Unfortunately, only pictures can tell the story now. The original asylum building was torn down in 1996 to make way for expansion. The Sauerkraut Cave is still there , but only as a curiosity. It’s entrance is marred by graffiti and only the brave – or crazy – dare enter it today. Other than the cemetery, the cave is the last vestige of the old grounds.

Baldez never told anyone what drew his interest in adding the adornment to the roof of Churchill Downs, but he gets credit for a lasting legacy, not only to horseracing, but to American culture in general.

Col. Winn knew it. “Joe, when you die, there’s one monument that will never be taken down,” he reportedly told Baldez.

He was talking about those famous Twin Spires.