The Man Who Put the Brick in ‘Brickyard’

By Ken Zurski

Carl G. Fisher was a bicycle enthusiast. He built them, he raced them, he even delicately guided one across a tightrope just to prove there versatility. He was nicknamed “Cripple,” or “Crip” for short, because his friends thought he was destined to suffer a permanent injury. As one worrisome acquaintance described: “He frequently, in bursts of speed, took spills and ended up with many bruises and cuts.”

Undeterred, after dusting off, Fisher would try it again.

That was his style.

Born in Greensburg, Indiana in 1874, as a young boy Fisher moved to Indianapolis with his mother after his parents separated. Due to a severe case of astigmatism, he dropped out of school early and worked odd jobs, like a grocery store clerk, to support his family. At age 17, along with his two brothers, Fisher opened a bicycle shop.

With the advent of the automobile, Fisher saw another business opportunity. “I don’t see why an automobile can’t be made to do anything a bicycle can do,” he told a friend. In 1904, Fisher converted his bicycle business into an automobile repair shop. To promote his new venture, he asked a crowd to gather at a downtown Indianapolis building. He then pushed a vehicle off the roof. The vehicle landed on its tires, still upright. The crowd roared its approval. It was showy and effective, similar in style to a more famously known promotional trickster named P.T. Barnum. Fisher later admitted he deflated the tires so the car wouldn’t bounce.

Despite his knack for self-promotion, Fisher had more serious concerns about the newfangled motor vehicle. First was being able to drive it safely in the dark. He invented a headlight that used compressed gas to light the way. It was a revolutionary idea. Soon, the Fisher-patented lights were being manufactured in plants throughout the Midwest. The process however was not safe for workers. The chemical tanks kept blowing up. “Omaha left at four-thirty,” one wire read announcing the unfortunate closing of another plant. The tanks were eventually lined with asbestos and the blasts stopped. The headlights became the standard and Fisher in turn became a very wealthy man.

With money and power in his hands, Fisher took to the automobile like he did the bicycle – with deering-do. He raced a modified Mohawk on small tracks at fairgrounds in Indiana mostly built with wooden boards. But Fisher wanted more. He wanted more speed. more thrills and more excitement. Inspired by European tracks that had long straightaways and sweeping curves, Fisher suggested a proving ground track in Indianapolis would be beneficial to the automobile industry as a whole, testing the limits of engines and body styles. Plus, the racing would be a hoot too.

He and other local financiers put up $250,000 in capital to build the track, a two-and a half mile oval, that became known as the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. On Aug 9 1909, the first car races took place. It was a disaster. Six drivers were killed along with two spectators. The race was scheduled for 300 miles, but Fisher mercifully stopped it at 235 miles. The drivers and their machines, Fisher explained, were not the issue. The problem was the track, made of crushed stone. The frequent tire blow outs led to disastrous and deadly results. Fisher had to make a change.

He recommended they pave the tracks with bricks instead. But it was costly. So he convinced his investors to help pay for it. Over 3-million bricks were laid. On Memorial Day 1911, the first 500-mile race was run. Driver Ray Harroun in a vehicle named “Wasp” won the inaugural contest with an average speed of just over 74 mph. “There were but four tire changes,” the winning vehicle’s manufacturer boasted the next day. “Three of the original tires finished the race.” The bricks, they subtlety implied, made the difference.

The track later picked up the moniker, “Brickyard.”

Fisher didn’t stop with improvements to racetracks however. He felt everyday drivers were being shortchanged by the lack of public roadways. At the time, most roads were just dirt paths and few went long distances. In 1912, at a dinner party for automobile manufacturers, Fisher unveiled an ambitious plan to build a highway that would span the country, from New York to California. He urged the auto executives to come aboard. Within 30-minutes, he had hundreds of thousands of dollars in support.

Ironically, the one man who refused to contribute was an automobile pioneer from Detroit who thought the automakers should stick to making automobiles, not roads. The government, he explained, should be responsible for that.

His name was Henry Ford.

Thanks to Fisher’s persistence, however, Lincoln Highway (today it’s portions are more formally aligned with the coast-to-coast Interstate 80), became the first transcontinental highway for motor vehicles.

But Fisher’s testament, such as it is, lie in the bricks. Still a fixture at the track’s finish line.

At Noon, it Still Looked like Midnight

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

The sun never showed up as usual in St Louis, Missouri on November 28 1939, a Tuesday.

The sky went black and stayed that way. In fact, for the next several days, the Gateway City remained mostly in the dark. A thick cloud of smog hovering over the streets putting filthy dust on surfaces and causing many to seek shelter indoors and away from the choking, blinding smoke.

But it’s not as if everyone wasn’t warned.

The burning of bituminous high-sulfur or “soft” coal to heat and power homes was at an all-time high. Winter was just creeping in and stoves were firing. The city could sense a growing problem, but had little recourse to stop it.

Long before, in 1893, a city ordinance was passed forbidding the emission of the “thick grey smoke” within the corporate limits. But enforcement was lax. And for many, what was the alternative? The city’s population grew and the coal debate just got worse.

In 1937, with coal use at dangerous levels, the St. Louis Dispatch announced a “citizen smoke committee” designed to warn others of the continued use of coal and come up with ways to make the air cleaner. One suggestion was “washing” the coal to reduce sulfur. Also, size was important. Smaller pieces of coal in the stove would restrict the fire many were told. Few followed the advice, so a smoke ordnance was passed that year which helped reduce emissions form factory smokestacks by nearly two-thirds. But that wasn’t enough. And it did nothing to curb use of coal in homes and small businesses.

Manufacturers of the precious commodity, mined mostly in Illinois, balked at the restrictions. After all, business was good and coal was in high demand. The cleaner anthracite coal was being mined and used in other states, but the Illinois mining industry had an abundance of bituminous coal to extract along the Mississippi River. Raymond Tucker, an assistant to the mayor, and the appointed Commissioner of Smoke Regulation, was skeptical, but optimistic. “Only time and experience,” he said, “will point the way toward an ultimate solution.”

Then the sky fell.

But it wasn’t entirely the city’s fault. A temperature inversion occurred, trapping the coal smoke close to the ground. Normally the air near the surface is warmer than the air above, but an inversion switches that polarity and stops atmospheric conversion. The air becomes still and heavy and a collection of dust and pollutants is suspended. Thick billowing smoke had been in the skies like normal, but it would typically rise. On “Black Tuesday,” as it was later dubbed, the smoke stayed and settled.

At noon that day, it still looked like midnight. Visibility was enhanced only by the glare of streetlights, the stream of headlights from an automobile, or the soft glow of a lit cigarette. Somewhere in the shroud of smoke a faint poke of sunlight could be seen, then shut off again. Many citizens went out as usual that day, but quickly realized nothing would come easy. “Let me off at Thirteenth Street and Washington,” a streetcar rider told an operator, then added: “If you can find it.”

That Tuesday was the worst day. “The winds were negligible,” the papers reported, “hardly enough to stir the choking, grey, atmosphere.” For the next week or so (some say it was for a full month) the smoke hung low, but gradually dissipated.

When the skies finally cleared, the same questions remained: How do we get the public to burn cleaner coal? The blackout was a wake up call. Most residents, for the first time, were ready to comply. The first anti-smoke law was passed, which helped, but it was America’s induction into World War II that greatly benefited the cause.

Since coal was in high demand during the war, the Illinois coal miners had other more important orders to fulfill and therefore not so reliant on public consumption. Without a pushback, Commissioner Tucker went shopping and found there were good mines in neighboring states, like Arkansas, selling the cleaner coal.

But that would take time. In the interim, an estimated 1-million people had to change their habits. After “Black Tuesday” they were informed how to slowly burn the “soft” coal” and reduce emissions. The “old way vs. the new way,” newspaper ads proclaimed, giving step-by-step instructions for using the cleaner “piling” method of burning coal and the benefits of adding a mechanical stoker.

It worked.

The following year, around the first anniversary of the blackout, on a morning when weather conditions were about the same and an inversion was possible, St. Lousians nervously waited for the smoke to descend again. They hoped their efforts to reduce or lesson the adverse affects of coal use was not in vain.

The sun came out as usual each day.

But this time it stayed.

Before There was Mickey Mouse, There was ‘Oswald the Lucky Rabbit’

By Ken Zurski

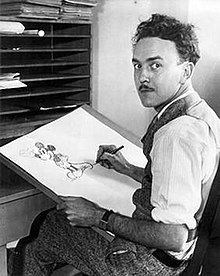

His face was round and his body was rubbery. He was sensitive, but headstrong. He laughed. He cried. For kicks, he could take off his long supple ears and put them back on again. His name was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and he was the first major animated character created by a man who would later become – and still is – one of the most enduring public figures of our time.

Walter Elias Disney was just in his twenties when Oswald came along. A gifted graphic artist from the Midwest, Disney had spent some time overseas during World War I as an ambulance driver and returned to the states to work for a commercial arts company in Kansas City, Missouri. Disney had a knack for business. He partnered with a local artist named Ub Iwerks and together they formed their own company, Iwerks –Disney (switching the name from their first choice of Disney- Iwerks because it sounded too much like a doctor’s office).

They dabbled in animation and soon were making shorts, basically live action films mixed with animated characters. They made a slew of little comedies called Lafflets under the name Laugh-O-Grams. It was a tough sell. Studios backed out of contracts and various offers fell flat.

Disney never gave up and soon they had a series called Alice the Peacemaker based loosely on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Alice was different and seemingly better. They used a new technique of animation, more fluid with fewer cuts and longer stretches of action. Alice, the heroine of the series, was a live person, but the star of the comedies was an animated cat named Julius. The distributor of the Alice shorts, an influential woman named Margret Winkler, had suggested the idea. “Use a cat wherever possible,” she told Disney, “and don’t be afraid to let him do ridiculous things.” Disney and Iwerks let the antics fly, mostly through their furry co-star.

When Alice ran its course and Disney was thinking of another series and character, he wanted it to be an animal. But not a cat, he thought, there were too many feline cartoons. That’s when a rabbit came to mind.

A rabbit he named Oswald.

It was a shaky start. The first Oswald short, Proud Papa, was controversial even by today’s standards. In it, Oswald is overwhelmed by an army – or air force, if you will – of storks each carrying a baby bunny and dropping the poor infants one right after the other upon Oswald’s home. He was after all a rabbit and, well, rabbits have a reputation for being prodigious procreators.

But this onslaught of newborns, hundreds it seemed, was just too much for the budding new father. Oswald’s frustration turns to anger and soon he brandishes a shotgun and starts shooting the babies, one by one, out of the sky like an arcade game. The storks in turn fire back using the babies as weapons.

Pretty heady stuff even for the 1920’s, but it wasn’t the subject matter that bothered the head of Winkler productions, a man named Charles Mintz. It was the clunky animation, repetition of action, no storyline, and lack of character development that drew his ire.

Disney and Iwerks went back to work and undertook changes that made Oswald more likable – and funnier. They made more shorts and audiences began to respond.

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit caught on. Soon, Oswald’s likeness was appearing on candy bars and other novelties.

Disney finally had a hit. But the reality of success was met with sudden disappointment. Walt had signed only a one-year contract, now under the Universal banner, and run by Winkler’s former head Mintz. The contract was up and Mintz played hardball. He wanted to change or move animators to Universal and put the artistic side completely in the hands of the studio. Walt was asked to join up, but refused. He still wanted full control. Seeing an inevitable shift, many of Disney’s loyal animators jumped ship. But Walt’s close friend and partner Ub Iwerks stayed on. Oswald was gone, but the prospects of a new company run exclusively by Walt were at hand.

Under Universal’s rule, Oswald’s popularity waned. Mintz eventually gave the series to cartoonist Walter Lantz who later found success in another popular character, a bird, named Woody Woodpecker. Oswald dragged on for years, as cartoons often do, and was eventually dropped in 1943.

Disney, meanwhile, needed a new star.

Here’s where it gets better for Walt. In early 1928, Disney was attending meetings in New York when he got word that his contract with Universal would not be renewed and Oswald was no longer his. Although he later said it didn’t bother him, a friend described his mood as that of “a raging lion.”

Disney soon boarded a train and steamed back west determined to carry on.

As the story goes, during the long trip, Disney got out a sketch pad and pencil. He started thinking about a tiny mouse he had once befriended at his old office in Kansas City.

He began to draw a character that looked a lot like Oswald only with shorter rounded ears and a long thin tail.

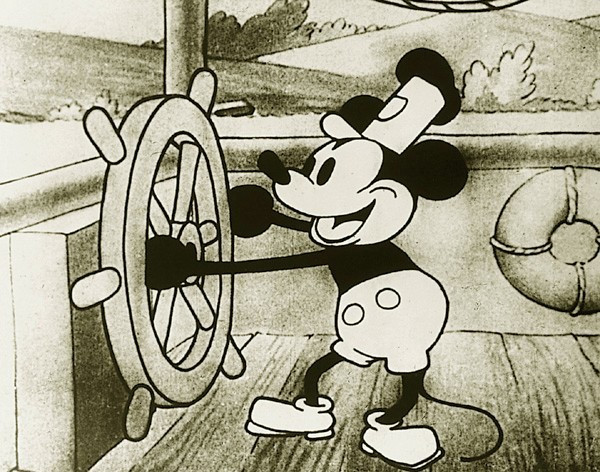

Steamboat Willie starring Mickey Mouse debuted later that year.

Two Trains, One Track: The Great Train Wreck of 1918

On July 9, 1918, near Nashville, Tennessee, in an area known as Dutchman’s curve, two trains collided head-on creating such a frightful noise that many claimed it could be “heard for miles.”

It was 7:00 on a warm summer morning and both trains on the Nashville, Chattanooga & St Louis line were running late.

The westbound or outbound passenger train to Memphis had just pulled out of Nashville’s Union Station packed with passengers. The eastbound train was heading inbound to the Nashville station from Memphis. Both veteran engineers had orders. The inbound train had the right of way on the curve’s one-way track. The outbound train would have to wait at the double-tracks just outside of the station for the other train to pass. But something went horribly wrong. A green light was given to the outbound train to proceed, meaning someone had seen or heard the incoming train pass. But when the tower operator checked his papers, there was no record of the Nashville-bound train coming through.

In reality, the inbound train was running nearly 35 minutes behind schedule.

The operator frantically telegraphed the dispatcher who immediately sent an urgent message back. “Stop him” was his order. But how? At the time, there was no direct communication with the engineers in either train. Only a warning whistle was used for emergencies. The whistle blared, but the outbound train was too far along for anyone to hear it. By this time, the inbound train was chugging to the curve.

Both trains were moving at top speeds of 60 mph. Then a moment of sheer terror. The engineer of the outbound train caught a glimpse of the other train coming around the bend, directly in his path. He pulled the emergency brake, but there wasn’t enough time. Then that sound that could be heard for miles. “The ground quaked and the waters of nearby Richland Creek trembled,” one writer later described. “The wooden cars crumbled and hurled sideways, hanging over the embankment. One train telescoped the other.”

In all, 101 people were killed, mostly traveling soldiers and African-American laborers from Tennessee and Arkansas. Many were leaving or returning to work at a munitions plant in the Nashville area.

Besides what went wrong, there was more scrutiny.

After only a few days of front page news, the press was accused of being mostly dismissive. Perhaps it was due to the number of war stories that filled the papers at the time. But some believe the wreck itself, while tragic, just wasn’t exploitative enough. Most of the dead were minority migrants and laborers. Many were killed beyond recognition. Basically, it just wasn’t as easily sensationalized as other disasters at the time, like the wrecks involving circus trains…or the fate of a fun-filled chartered steamboat.

Four days before the Nashville train wreck another tragedy hit the papers that shook a nation. On July 5, a wooden steamboat named the Columbia collapsed and sank in middle of the Illinois River near Peoria, Illinois. The 87 dead were mostly women and children enjoying a holiday cruise to a local amusement park. The survivor stories that followed were stark and dramatic. “The only thing that kept me afloat,” one woman passenger reported, “were the bodies beneath me.”

The investigation that followed the train wreck, cited human error, specifically blaming the man who could not defend himself, the engineer of the outbound train, David Kennedy. Only speculation supports the theory that Kennedy mistook a switch engine hauling empty cars for the inbound train. Kennedy was killed instantly in the wreck. A folded “schedule” was reportedly found underneath his body.

The other engineer William Floyd was also killed. He was one day from retirement.

The Nashville wreck to this day is still the deadliest train accident in the history of the U.S.

Bobby Leach: A Minute Over the Falls

by Ken Zurski

Bobby Leach was not the first person to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. That honor belongs to Annie Edson Taylor who in 1901 escaped the treacherous drop from the horseshoe-shaped falls with only a slight gash on her head. Luckily, she survived to deter others from copying her foolish stunt. “If it was with my dying breath,” she said after the jump, “I would caution anyone against attempting the feat.” It was a stern warning. “I would sooner walk up to the mouth of a cannon knowing it was going to blow me to pieces,” she added, “than make another trip over the Falls.” Most heeded her desperate plea. Then came Leach.

If Bobby Leach heard Taylor’s words of caution, he likely took it as a challenge. Ten years later, in 1911, Leach would attempt the same stunt, also dropping off the horseshoe part of the Falls. “The first man to try it,” the newspapers trumpeted, perhaps finding no other angle to the story. But for Leach it was just part of a grand adventure. He was a daredevil and this is what daredevils do.

Leach was already a showman and acrobat, working in the circus and performing death defying feats of strength and endurance to large audiences. His risky balloon ascensions were popular and his parachute jumps – one for a distance of two miles – made people gasp with delight. In 1907, as legend has it, Leach was a spectator at Madison Square Garden in New York when a man tried to jump 125 feet from a platform to a large bucket of water. Leach was envious. When the jumper missed the bucket and died instantly, Leach supposedly rose to his feet and proclaimed, “I can do that.” Whether he attempted that feat is not known, but he did include more dangerous stunts in his own act.

In 1908, he announced his intentions to go over the Niagara Falls.

“In a rubber ball,” he exclaimed.

Leach had planned to jump the Falls in a large rubber ball, hoping to bounce of the jagged rocks at the bottom. He scrapped the idea, however, when others convinced him it likely wouldn’t work. Leach retooled his thoughts. Like Annie Taylor he would use a fortified barrel. But it was a barrel in name only. About nine-feet long and three-feet wide, it looked like a large steel cylinder with a manhole-sized opening and heavy cover. A small one inch hole, plugged by a cork, could be used for air if needed. Otherwise, the craft was water-tight. Inside, pillows were placed on each side and a webbed netting suspended the body, keeping Leach from violently banging the sides.

On July 25, 1911, the barrel was towed to the site at the top of the Falls and Leach climbed in. The scene from this point is best described by an eyewitness, a photographer named Walter Arthur, who was attempting to get motion picture footage of the event. “I was stationed on the bank at the bottom of the Falls with my motion picture machine ready,” Arthur recounted. “And I don’t mind saying that I never expected to see Bobby Leach again.”

Suddenly I saw the black shape of the barrel with its sharp wooden nose pointed on the brink. It hung there for a few seconds before it plunged down one hundred and sixty-eight feet to the river below. Leach had built out blunt wooden noses of heavy timbers, bolted fast to the iron ends of the barrel. The idea was that these wooden noses would act as buffers from the rocks and prevent them from smashing holes on the ends. As it turned out, this was a good idea, probably saved his life, for after its big drop the barrel struck nose on and tore away most of the planks on both ends.

Arthur says the barrel stood up on end for several minutes like it was wedged in some rocks then began to move with the current.

We were waiting at a point in the powerhouse cove where the control barrels had floated. We thought he would come out here, but he did not come. A minute passed, then two minutes, and we searched the smooth black surface where the “Maid of the Mist” was lying ready to help. Nothing! Three minutes! It seemed like hours, and then a little distance off from the shore we made out the black shape of the barrel sweeping on towards the rapids. Everybody yelled and big strapping fellow from the firehouse leaped into the river and struck out bravely. We saw him swim up to the barrel and throw one arm over it and turned like he was struggling, then two other young fellows rushed in and among them they brought the barrel to the bank.

Leach fainted during the fall, was banged up, but still alive. The rescuers used stimulants to revive him, then laid him out on a stretcher for a closer look. It wasn’t good.

At the hospital, the news was dire, but not life threatening. Both kneecaps were shattered and his jaw bone was cracked. He spent twenty-three weeks in the hospital recovering. When he was finally released, Leach found acceptance in Europe where he took his dented barrel and went to exhibits and conventions and reportedly did smaller- but still dangerous – stunts to appreciative audiences overseas. His return to the Falls was just as successful. He delighted locals with attempts to swim under the rollicking waters and made several parachute jumps out of an airplane over the gorge.

In 1926, Leach returned to Europe where he visited New Zealand and Austria. He never made it back. While strolling the New Zealand countryside by foot, Leach slipped on an orange peel and heard a loud pop. He broke his leg so severely it had to be amputated. Gangrene set in and killed him. “Not a banana peel,” one writer aptly jested about Leach’s unfortunate and unlucky demise, “the greatest fall artist of all time died from a fall off an – orange peel.”

Leach’s place in history is perhaps more dubious considering he was the first person to jump the Falls after Taylor’s inaugural attempt. The “Heroine of Niagara Falls” tried to stop others from trying the feat, but that didn’t deter Leach. His decision to jump may have inadvertently spurred on others to publically make successful and tragically unsuccessful attempts that continues to this day.

Leach also benefited off his popularity, but Taylor did not. She expected to get rich for her efforts, but died a pauper.

Even by today’s standards, these daredevil barrel jumpers would certainly be lauded for their efforts. But perhaps one aspect of their stunt would have received more attention and likewise, skeptical debate: their ages.

Leach was in his 50’s when he jumped off the Falls. Taylor was 63.

Why this Website? There’s History Behind It

Research takes you to many places. Usually while researching a topic, I find an interesting person or event I haven’t heard about or just plain forgot. I store it away hoping to retrieve it someday and use it in context within a bigger project. Maybe a new book.

But I cant get it out of head.

These are the figures from our past, the once-somebodies, whose stories for some reason – and usually no fault of their own – are now lost to time. This obscurity, however, does not diminish their past accomplishments or achievements. These are tales just as fascinating and complex as more familiar events and figures, the ones we know more famously. Some of these characters may have even played a bit role in it.

So I decided it’s time to retell and revive these stories. And this website is the result. I’ll be posting the first story soon.

Please, click on the “follow” button and start enjoying the history of the unremembered.

– Ken Zurski, author

Welcome to UNREMEMBERED!

History has a way of remembering and forgetting certain people and events. Some may have chosen this path to anonymity and others may have simply been part of a fleeting fame, once recognized for their importance and influence, now lost to time. I’ve always been fascinated by these lesser-known personalities, the so-called other people, whose contributions to our past have either been discarded, neglected or simply put out of mind. These are the stories I want to tell. The stories of the unremembered.

“This site is dedicated to historical events and characters who were once famously known – now forgotten.” – Ken Zurski, author

- ← Previous

- 1

- …

- 34

- 35