Ken Zurski Unremembered

The Introduction of Mrs. Claus is a Real Tearjerker

By Ken Zurski

“The Christmas Legend” is a short story written in the mid-nineteenth century by a Philadelphia missionary named James Rees. It tells the tale of a destitute American family that receives an unexpected visit from a couple of strangers on Christmas Eve. The constructive narrative sets up a deep exploration of family, loss and forgiveness; a classic Christmas formula. But the story itself is not widely known. In fact it would likely be completely forgotten had it not been for one word- “wife.” Today, it is cited as being the first time Santa Claus was associated with a spouse. It literately introduced the character we know now as Mrs. Claus.

Published in 1849, “The Christmas Legend” was part of a collection of 29 short stories written by Rees and compiled under the title, “Mysteries of City Life, or Stray Leaves from the World’s Book.” Each story is cleverly presented to represent the dissimilarity of many leaf types. For example, the maple leaf, Rees writes, is “golden and rich” and presents a sunnier disposition, while another like the gum tree leaf has a “bloody hue” and “stands fit emblem of the tragic muse.” He likens authors after the “forest trees” which “send forth their leaves unto the world.”

“And by what emblem shall we appear amongst those clustering trees,” Rees explains. “Let us see – Ah! The Ash Tree leaves are like ours, humble and plain to see, but hiding the silver underneath.”

In “The Christmas Legend,” Rees uses the spirit of the holiday to emphasis this point.

Here is the abbreviated story…

A family of four, mother and father, daughter and son, are sitting near the fireplace on Christmas Eve. The two children, especially the daughter, wonders if she should hang the stockings for Kris Kringle to come. But her mother raises doubt. There are more important things in life than earthly possessions, she states: “Poverty keeps from the humble door all the bright things of the earth, except virtue, truth and religion, these are more of heaven and earth, and are the poor man’s friend in time of adversity.”

“I thought that Santa Claus or Kris Kringle loved all those who are good, and haven’t I been good?” the daughter asks confused.

The mother tells her to leave the stocking up. “Customs at least should be observed, and perhaps the young heart may not be disappointed,” she explains.

The father is more introspective. He anguishes over a lost family member, the eldest child, another daughter who apparently ran away with a “dissipated” man seven years before and hasn’t been seen or heard from since.

Then there is a knock at the door.

Two strangers appear out of the night, an elderly couple carrying a bundle with “all their worldly wealth.” They ask how far away they are from the city and the father tells them it is “two miles.”

“Two miles?” the stranger says sadly, “we will not be able to reach it tonight. My dear wife is nearly tired out. We have traveled far today.”

The father invites them in and offers his best bed for them to rest. The strangers inquire if this is their whole family. “No. No,” the father says, “we had one other – a daughter.”

“Dead; Alas we all must die,” the old woman responds.

“Dead to us,” the man answers. “But not to the world. But let us speak of her no more. Here is some bread and cheese, it is all poverty has to offer, and to it you are heartily welcome.”

There is a silent pause, then the sound of cheerful merriment, music and laughter, is heard through the open windows and doors. It’s their rich landlord, the father explains, mocking the poor. The old man interjects. “Ah, sir, human nature is a mystery, this is one of the enigmas, and can only be explained when the secrets of the hearts be known.”

The next morning, Christmas Day, the family awakes to find their small room filled with presents: books and games and toys. “O Father, Kris Kringle has been here,” the little girl says excitedly. “I am so happy.”

Here Rees as the narrator sets up the moral of the story. “There are moments when the doors of memory and the bright sunshine of hope make the future all clear,” he writes. “Sorrow is not eternal; it has its changes, its stops; its antidote; they came in the moment of trial and – Presto! The whole scene of life is venerated in the pleasing colors of fancy.”

And that’s when something totally unexpected occurs. The old couple reappears to the family not as as they came, but as a vibrant young couple. The children recoil from fright, but the parents are curious. “How is this?” the father asks. “Why these disguises —“

“Hush, sir,” the once old man says laughing. “This is Christmas morn and we now appear to you not as Santa Claus and his wife, but as we are, the mere actors of this pleasing farce.”

The couple recognizes the old woman’s new face. It’s their long lost daughter. The girl hugs her mother, but the father is more skeptical, angry and weary of atonement. He lashes out at the girl as she approaches him. “Stand back!”, he shouts, then chastises the man who stands with her as a “paramour.” She begs him to reconsider. “No Father he is my kind and affectionate husband.”

“Ah, husband,” the father replies. He reaches for his daughter. They embrace.

Rees goes on to explain the girl ran away because she was “young and foolish” but loved the man who was forbidden from her home. They left America for England where her new husband became heir to a large estate. She sent letters home, but they were never received. Now she had returned back to her family on Christmas Day. A gift of love and hope. “Can you forgive me?” she asks.

“Say no more, all is forgotten. All is forgiven,” the father tells her.

Even though it is thinly defined, the mention of Santa Claus’s wife in “The Christmas Legend” is widely considered the first ever to appear in print. Two years later in 1851, the name Mrs. Santa Claus would be mentioned again in a story published in the Yale Literary Magazine. History tells the rest.

Today Mrs. Claus is considered a kindly old woman who helps her husband on Christmas Eve, tends to his colds, stitches his clothes, and feeds his “round belly,” usually with homemade cookies and milk.

“There are many interesting facts both historic and fabulous connected with the ceremonies, customs and superstitions of this day [Christmas], which if collected together today would make and curious and interesting book.” Rees explains in the introduction to his tale.

Apparently, he added to that.

Recognize this Actress? You Might be Surprised.

By Ken Zurski

A veteran of stage and screen, Billie Burke began her Broadway and film acting career in 1906 at the age of 22.

She appeared in numerous stage and screen roles (silent films) and in 1914 married another show business impresario , Florenz “Flo” Ziegfeld Jr, of Zeigfeld Follies fame.

In 1921, Burke retired from performing thanks to a boon in the stock market and good investments.

However, in 1929 after the Black October crash, the money was gone.

Burke went back to work appearing with many top Hollywood heavyweights like Lionel Barrymore whom she co-starred in the most acclaimed and defining role of her career: Millicent Jordan, the “hapless, feather-brained lady with the unmistakably high voice,” in 1933’s “Dinner at Eight.”

Although it wasn’t her last appearance in the movies, in 1939, at the age of 54, Burke played a character for which she is most remembered today…

Glinda the Good Witch of the North in “The Wizard of Oz.”

The Hand-Picked Ornament that Became the Stanley Cup

By Ken Zurski

In 1891, Charles Colville, secretary for the Lord Frederick Stanley, the British appointed General Governor of Canada, was ordered to sail back to England and return with a hand-picked ornament.

Stanley had something particular in mind and Colville knew just where to look.

On Regent Street near Piccadilly Circus, he stepped into the shop of George Richmond and Collis Co. and spotted a “silver bowl lined with a gold gilt interior.”

Colville bought the bowl for 10 guineas, the equivalent of about 10-thousand U.S. dollars today.

Stanley was ambivalent at first. “It looks like any other trophy,” he remarked.

Generally, though, he was pleased.

In 1893, the first Stanley Cup, as it was called, was awarded to Montreal, the champions of the Ontario Hockey Association. Stanley, a big hockey supporter, offered the trophy as a gift.

The first Cup presentation however came with a dubious start.

Lord Stanley’s team was Ottawa. So animosity between the two teams was apparent. When Montreal was awarded the inaugural cup bearing Stanley’s name, only a few players were on hand.

Even more telling, no Montreal team officials bothered to show up.

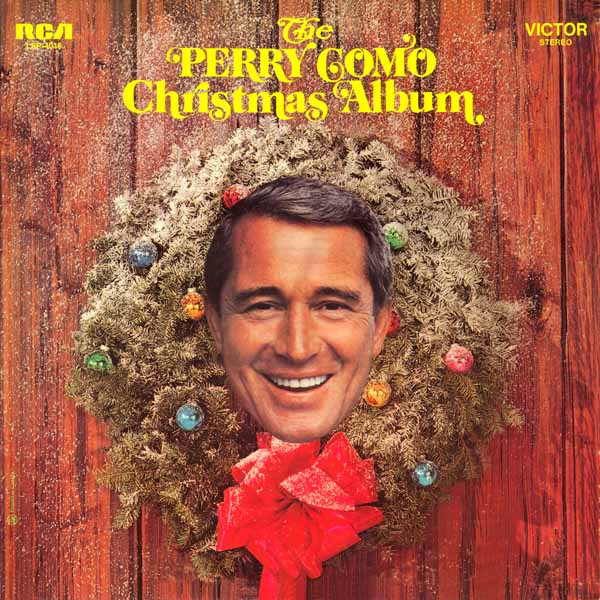

‘Good Guy’ Perry Como was one of the TV Kings of Christmas

By Ken Zurski

Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time. Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television special and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Como’s face and voice became synonymous with the sounds of the season.

That said he may have been the most misunderstood as well.

Como was a one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced his craft incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week. Even Perry was surprised by the remuneration. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the town’s perceived association with mobsters and legalized prostitution, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduce his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually standing backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many wondered how much of it was real. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for 46 consecutive years ending in 1994, seven years before his death in 2001 at the age of 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)

As Christmas Crooners Go, Perry Como Was As ‘Pure As The Driven Snow’

By Ken Zurski

Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time. Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television specials and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Como’s face and voice became synonymous with the sounds of the season.

Today, however, in a more crowded market for Christmas music and numerous more versions of favorite holiday classics (and new ones too) from more contemporary artists in all genres, Como’s versions might get lost in the mix.

But it’s still in there.

That said, as a performer, he may have been misunderstood as well.

Como was considered one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced and rehearsed incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week, admittedly a large sum for a Vegas act at the time. Even Perry was surprised. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the desert town’s reputation of gambling and prostituition, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduced his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament and sleepy manner was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many had to ask if it was real or just an act. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for three decades ending in 1994, seven years before his death from symptoms of Alzheimer’s in 2001. He was 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)