Uncategorized

The Stinking Truth About The Phantom’s Opera House

By Ken Zurski

(Note: This story was inspired by a playbill for The Phantom of the Opera at Her Majesty’s Theater in London).

In Paris, around the mid 1800’s, a man named Eugene Belgrand was hired to overhaul a system of underground sewer tunnels that were built nearly five centuries before and while still in use, was in desperate need of repair.

The plan was to make the tunnels more functional in the era of modernized sanitation, which at the time, wasn’t very sanitized at all. That’s because in 19th century Paris, as in other large European cities, waste was still being tossed onto the street, washed away by the rain, and ending up in filthy rivers, like the Seine, where even the shamelessly rich and privileged who strolled the fancy stone walkways of its shore, were appalled.

The old tunnels could still be used, officials determined, but needed reinforcements and additions to be more effective. The French engineer’s task was simple: make it better.

That of course was the practical reason for the upgrade. The more emotional plea came from Parisons who were just plain sick of the consistently putrid smell and squalor conditions. Women especially complained that they were forced to carry parasols all the time for fear of being dumped on from windows above. So Belgrand reshaped the tunnel routes, put in more drains, built more aqueducts, and started treatment plants. Eventually, 2,100 km (1300 miles) of new pipes were installed and the Paris sewer system became the largest of its kind in the world.

But not necessarily the most reliable.

Many of the early tunnels were built tall and wide, but not designed for uniformity. The chutes weren’t long enough or sufficiently sloped enough to keep the flow moving. Victor Hugo in his 1862 novel Les Misérables called the Paris sewers a “colossal subterranean sponge.” Even improved, the waste would still back up and somebody – or something – had to unclog it. Workers would do their best to dislodge the muck first by hand – usually with a rake. When it was too deep, or wouldn’t budge, dredging boats were used with some success. But when a boat didn’t work, by far the most effective method was using the wooden ball.

Yes, a wooden ball.

The ball was around 5-feet in diameter and resembled a wrecking ball in size, but not nearly as heavy. Constructed out of wood and hollow inside the outside was reinforced with metal for more solidity.

Some mislabeled it an “iron ball,” assuming it was solid throughout, which if true would have been far too cumbersome to move. Several men with ropes could easily lift the wooden ball or pull it into position. With a push the ball was sent careening into a tunnel. (Think of a bowling ball rolling down an alley gutter – only on a much larger scale.)

A London society newsletter in 1887, praised its dependability: “As soon as it comes to a point where there is much solid matter in the sewer it is driven against the upper surface of the pipe and comes to a standstill. Meanwhile the current gathering strength behind it rushes with tremendous force below the ball carrying away all sediment or solid matter and leaving the course clear.” The ball worked well for a time, but eventually its effectiveness wasn’t enough. By the early 20th century, a more streamlined method was deployed that harnessed and released rain water. The increase in the current’s velocity would flush the obstruction away. “The rain which sullied the sewer before, now washes it,” Hugo declared.

The Paris tunnels are still in use today and tourists to the city can visit a museum dedicated to the centuries old system. Guided tours lead patrons through narrow stairwells and dank rooms as the sound of waste water is heard rushing through the tunnels below. Even the wooden balls are on display.

But the Paris tunnels have more history than just collecting and deporting sewerage

When the famous Paris Opera House was built in the 1870’s, architect Charles Garnier’s construction team ran into a problem. While digging the foundation wall, they hit an arm of the Seine, likely an extension of the tunnel system that led to the river. They tried to pump the water out but it kept coming back. So Garnier designed a way to collect the water in cisterns thereby creating an artificial lake nearly five stories beneath the stage.

It is in this “hidden lagoon” that author Gaston Leroux had an idea for a book that he claims was based on real events. In the story titled Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, a troubled soul named “Erik,” who is grossly disfigured, escapes to the catacombs and the lake below the Opera House. By banishing himself from society, “Erik” became a “ghostlike” figure until a sweet soprano’s voice lures him back to the theater’s upper works.

In the popular musical version that came out many years later, the “Phantom of the Opera” takes his unsuspecting love interest Christine on a gondola ride through the underground lake.

A scenario that if true, would be far less romantic than portrayed in the famous theatrical production.

Whether or not the lake was connected to the tunnels or ran directly from the Seine River, didn’t matter. The result would still be the same. Instead of being mesmerized by the experience as if in a fantasy world, in reality, the lovely Christine would likely be holding her nose, gagging, or worse.

Cue the music.

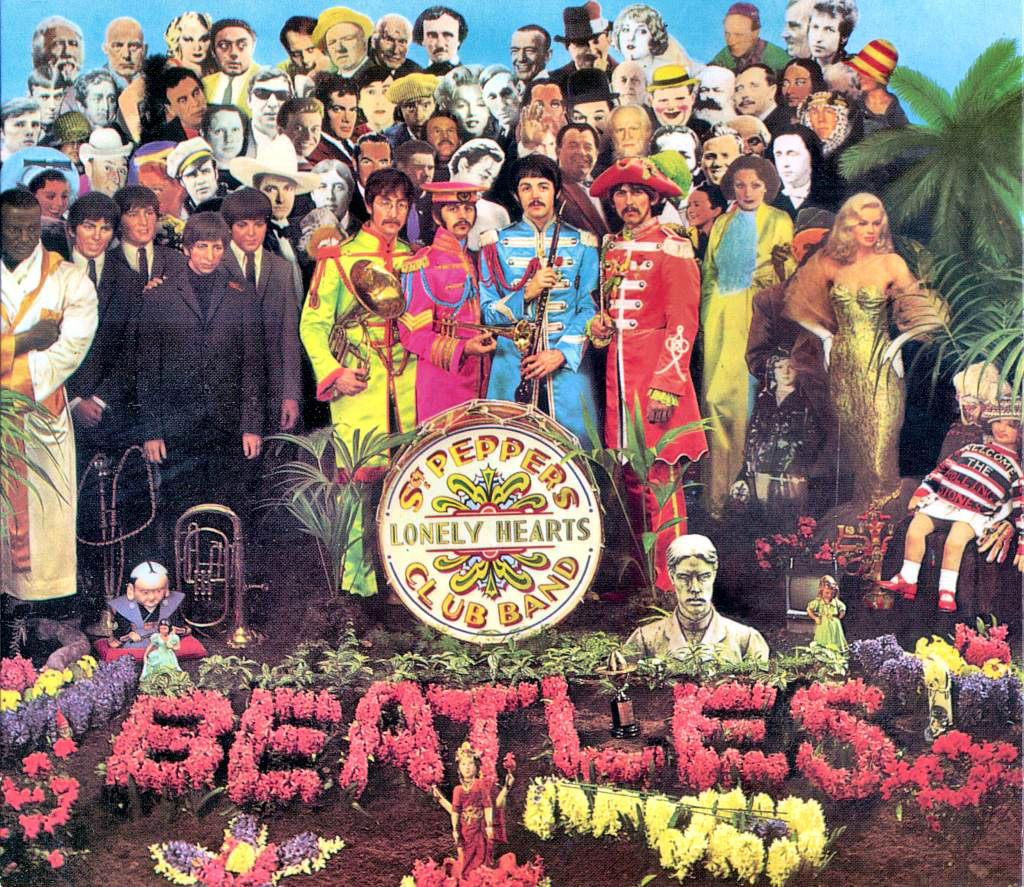

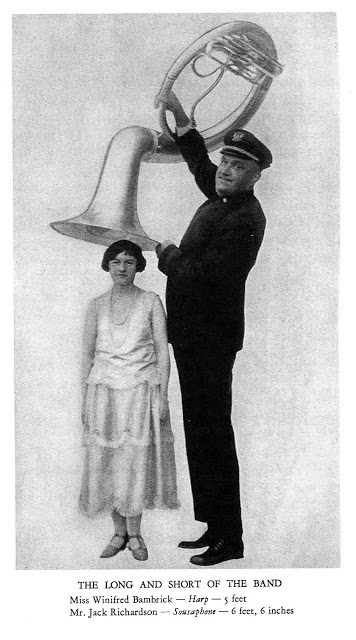

A Salute to the Long Play (LP) Microgroove Vinyl Record

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

In 1948, the LP (Long Play) microgroove vinyl record was introduced by Columbia Records for the sole purpose of playing more music on a phonograph or analog sound medium. Circular in shape like its predecessors, the LP was larger in diameter at 16-inches and turned at 33 1/3 revolutions per minute, much slower than previous versions.

The LP itself was designed to replace the 12-inch records being manufactured for RCA Victor player’s in the 1930’s. The smaller plates had tighter grooves and less background noise, but unpredictable sound clarity overall.

The larger LP’s were slow to catch on at first, representing only a slight percentage of sales for consumers who were accustomed to the smaller size, faster speeds (78 rpm) and shorter play time. But as home stereo systems improved, LP’s were streamlined back to 12-inches and quickly became the preferred choice of buyers.

In the 1960’s and continuing into the 70’s, music artists such as the Beatles and Pink Floyd found a niche by exploiting the availability of time per LP side. They began experimenting with varying layered pieces of music, thereby making, marketing and selling albums with longer songs and conceptual themes. In some instances, two LP’s were included.

Then in the 1980’s, thanks to MTV and the demand to buy popular music, chain record stores opened in malls across America and record sales – included the smaller 45 rpm singles – continued to rise.

But it wouldn’t last.

Introduced in the mid 80’s, the new compact disc format (CD) was cheaper and less expensive to produce. The CD’s were about the same price as a vinyl album, but a CD player was costly. Eventually demand drove down the price and by the 1990’s, the age of the LP mostly disappeared. Mainstream record stores transitioned to stocking and selling only CD’s on their shelves.

Recently however, with no physical attributes attached to digital music, there’s been a surge in demand for vinyl. Newly pressed vinyl records of repackaged older and some newer music has become popular as turntables sales have increased as well. In fact according to the Recording Industry Association of America‘s midyear report for 2019, vinyl album sales may soon overtake sales of CD’s for the first time since 1986. This trend has prompted many new artists who have only produced music for the CD and digital markets to promote vinyl packaged versions of their albums as special editions.

According to c/net: “Just because vinyl may soon outpace CDs doesn’t mean music lovers are trading in their iTunes accounts for turntables. Streaming remains the most popular way to consume music, accounting for 80% of industry revenues, and growing 26%, to $4.3 billion, for the first half of 2019.”

Bu the LP just wont die. Today, original LP’s from the early 40’s to the mid 80’s are considered nostalgic and collectible. Many privately owned record shops, or independents as they are called, continue to thrive by specializing in rare or out of print editions. And online markets, swap meets and thrift stores are filled with opportunities to sell or purchase used albums.

A Telegraph Operator’s Night To Remember

By Ken Zurski

Late in the evening, April 14, 1912, on a passenger liner in the Atlantic Ocean, telegraph operator Harold Cottam was getting ready for bed. Cottam was the only wirelessman on board the ship bound for Gibraltar by way of New York. The day had been busy as usual and Cottam was looking forward to shutting it down for the night.

The radio, however, remained open.

“Why?” he was asked later in an inquiry.

“I was receiving news from Cape Cod.” he replied. “I was looking out for the Parisian, to confirm a previous communication with the Parisian. I had just called the Parisian and was waiting for a reply, if there was one.”

At this point, Cottam might have been asked about allegations, based on the late hour, that he was listening to Cape Race in Newfoundland for English football scores, clearly against regulations. But under oath, he said it was only the Marconi base at Cape Cod he was monitoring.

Cottam says he kept the telephone on his head with the hope that before he got into bed, a message would be confirmed.

“So, you were waiting for an acknowledgement [from the Parisian]?”

“Yes, sir,” Cottam conferred

Cottam says he received no word from the Parisian, but did get a late transmission from Cape Cod to relay a message to another ship steaming to New York from England’s Southampton shore. The large ocean liner had been sailing for several days and the messages – mostly personal correspondence for passengers – did not go through. Perhaps Cottam, who was closer, would have better luck. “I was taking the messages down with the hope of re-transmitting them the following morning,” Cottam said.

But Cottam didn’t wait until morning. He immediately tried to reach the ship.

“And you did it of your own accord?”

“I did it of my own free will,” he replied

Cottam said he sat down at the telegraph desk and tapped out these words: “From the Carpathia to the Titanic are you aware of a batch of messages for you”

The reply came quickly.

CD followed by Q, a general distress call.

“And what did it say?” he was asked.

“Come at once,” Cottam explained,

“Come at once.”

The Frankenstein That Created a Monster – Painting

By Ken Zurski

Godfrey Nicolas Frankenstein, despite the name, was no mad scientist. Quite the contrary, he was a painter. But like the fictional Dr. Victor Von Frankenstein, he also had a vision that consumed his thoughts, his passions, and his ambitions for nearly two decades of his professional life.

It all started in 1844 when he visited Niagara Falls.

A visit to the Great Falls, especially by a painter was not unusual at the time. Plenty of artisans found the vastness of the Falls a great challenge. They would sit for hours and attempt to recreate its beauty either on canvas, paper or wood engravings. Many realized a single rectangle was too confining. They tried long strip paintings, panoramas, curved cycloramas and three dimensional dioramas, anything to replicate what it was like to see the Falls in person.

Frankenstein was a natural artist. He came from a family of painters who migrated from Germany to New York City when Godfrey was just 11. Already a prodigy, Godfrey began designing signs for money which turned into his own full-fledged sign-making business at the age of 13. At nineteen, he opened a portrait studio in Cincinnati. Two years later he was the first president of that city’s Academy of Fine Arts.

In 1844, at age 24, he went to the Falls.

The trip changed him. Now he had a purpose as an artist to create a lasting legacy. This was his plan: He would paint murals of the Falls , perhaps hundreds, all from different perspectives and then show them to audiences one at a time, like a moving picture, telling a story in the process.

Year after year, for nearly nine years, he went back to the Falls. He went during the changing of the seasons making small sketches of one angle the first year followed by another angle the next. He bravely stood in all kinds of weather. He drew the Falls in contrasting and opposite ways: by moonlight and in bright sunshine; before and after a rainstorm; and during a snowfall followed by a thaw. Each time, Frankenstein would set up his easel and produce scene after glorious scene. He sketched the Falls and it’s surroundings from the top and from the bottom, close up and far away and from one side to the other.

Frankenstein then began a five year process to transfer the sketches to canvas. He picked 80 to 100 good drawings and copied each one to single panels that stood at least eight foot high. The end product was a roll of canvas that when unfurled was nearly 1000 feet long. When it was displayed, one panel would be viewed followed by the next, creating a seamless spectacle of broad landscapes and augmented perspectives. In addition, the audience would get a geology lesson. Frankenstein cleverly juxtaposed scenes from different years to show the changes, including the rock slide that dropped the overhang known as Table Rock into the churning waters below.

“Frankenstein’s Panorama” as it was called, was a huge hit. In 1853, thousands flocked to the Broadway Amusement Center in New York to sit in the dark and watch the scenery unfold . Live music played and commentary by Frankenstein himself completed the entertainment. And all this for only 50 cents.

Reviewers were just as enthralled: “We see Niagara above the Falls and far below…We have sideways and lengthways; we look down upon it; we are before it, behind it, in it….into its spray on the deck of the Maid of the Mist; tempting its rapids among the eddies; skimming its whirlpool below…”

One commentator didn’t shy away from the works massive size and realism: The spectre of death seemed implicated in the medium’s own mode of representation; like a cadaver…the canvas resembles a living being…and yet there is a paradox in the close resemblance to death…”

In 1867, Frankentstein traveled to Europe and spent two years abroad painting. “Europe acknowledged that Mont Blanc and Chamont Valley never before have been painted with such power and beauty,” the Cincinnati Enquirer reported. It is said that popular English songstress Jenny Lind bought many of Frankenstein’s paintings and brought them back to London.

Frankenstein would also have a cliff named after him, a 1000 foot high rock formation near the Saco River in the White Mountain National Forest of New Hampshire. “This giant rock formation looms above the highway and seems to bear a profile of Frankenstein’s Monster embedded in the rock,” a hiking trail website describes, then clarifies: “However, the cliffs were, in fact, named for a painter.”

Why the cliff is named after Godfrey is not clear. Most people who visit the park understandably make the connection with Mary Shelly’s fictional monster.

Godfrey’s family likely had no idea the immortalizing to come when they innocently adopted the surname in 1831. At the time, Shelley’s book originally named The Modern Prometheus had been out for over a decade. The title was changed to Frankenstein during it’s second printing in 1823. Still it took years for the work to be fully appreciated.

In the book, Shelley’s protagonist, Dr. Frankenstein turned a passion into an obsession and literally creates a monster that ultimately destroys him.

Godfrey Frankenstein, the painter, had better results.

The name, however, seems to fit perfectly.

(Sources: Niagara: A History of the Falls by Pierre Berton)

She Won a Golf Match Into History and Didn’t Even Know It

By Ken Zurski

In 1900, 22-year-old Margaret Abbott was an American in Paris studying art and living with her mother when she read a newspaper ad looking for women to compete in a golf tournament.

The contest, the ad read, was open to all amateurs.

So Abbott, a skilled golfer back in her hometown of Chicago, took a break from her studies and urged her Parisian friends, even her mother, to enter the contest.

Together they played a nine-hole match, which to no one’s surprise, Abbott won by two shots and a total score of 47.

Her closest opponent the papers reported, “Had more than one piece of luck in getting bunkered and hitting trees.” Abbott’s mother, Mary, an accomplished novelist, finished 18 strokes behind her daughter.

Abbott was modest in victory, playfully claiming it was due to her conservative attire. “[The other ladies] apparently misunderstood the nature of the game,” she said, “and turned up to play in high heels and tight skirts.” Abbott, for her part, wore a long dress that swept the grass.

Abbott may not have known it at the time, but the Olympic Games – the second of its kind- was being held in Paris that summer.

Or was it?

No one was quite sure.

By today’s standards, the 1900 Games in Paris were an unorganized and confusing mess. There was no opening or closing ceremonies and contests were spread out over six months. In fact, there was so much confusion about schedules that few spectators or journalists were present at the events, which were so slipshod in preparation, that no one, not even the participants, knew if it counted.

Despite this uncertainty, nearly 1000 athletes showed up to compete. And for the first time, women, were included too.

Abbott by association, was one.

That’s because the sport of golf – and the match Abbott won – turned out to be a part of the overall competition.

So Abbott, who never knew she was competing for such an honor, is considered the first woman to win a gold medal at the Olympic Games.

A distinction which comes with a clarification.

No medals were awarded that year.

For her efforts, Abbott won a porcelain bowl.

The Doctor Who Prescribed More Quiet Time

By Ken Zurski

In the late 1800’s, Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell came up with a treatment for those suffering from mental and physical exhaustion.

The “Rest Cure,” as it was called, was a radical 6 to 8 week program that consisted of bed confinement and a special diet, like drinking heavy milk fats. The most important feature of Mitchell’s plan, however, was an environment of relative quiet and relaxation. No physical activity allowed. None. Even speaking was discouraged. And walking – forbidden.

Patients, mostly women, were ordered to limit any movement while in bed, usually left alone for long stretches, and dependent on others to wash and feed them. Mitchell believed the inactivity or “rest” increased the patient’s weight and blood flow.

He also dabbled in electrical therapy.

Mitchell was no quack. He had a degree from a respected Philadelphia medical institution and became a specialist in neurology, a relatively new science. Eventually his brain work led to helping Civil War veterans who suffered from nervous maladies. He is known to have coined the phrase,”phantom limb,”referring to the recurring sensation of a lost body part due to injury or amputation.

Mitchell’s work was both groundbreaking and experimental. But mental illness was still undefined and many women sought answers for their incessant tiredness and melancholy moods.

Writer Virginia Wolfe was one. She followed Mitchell’s plan, but later ridiculed it. “You invoke proportion; order rest in bed; rest in solitude; silence and rest; rest without friends, without books, without messages; six months rest; until a man who went in weighing seven stone six comes out weighing twelve,” she wrote.

Another writer, Charlotte Perkins Gilman went even further. She wrote a scathing story about the treatment that caused her to “go insane.”

Gilman’s short story, titled “The Yellow Paper,” was based on a character who unsuccessfully goes through the “Rest Cure.” The “yellow paper” in the title refers to the wallpaper in the room, which comes to life and mutates into various shapes and sizes, slowly driving the sheltered patient insane. “The whole thing goes horizontally,

too, at least it seems so, and I exhaust myself in trying to distinguish the order of its going in that direction.”

Upon hearing of Gilman’s criticisms, Mitchell’s advice back to her was twofold: Get more rest, he implied, or in essence, stop writing.

The bickering aside, Mitchell’s reputation was solid. The painful hand and foot condition, Erythromelagia, was originally named Mitchell’s Disease after him. Even Sigmund Freud’s famous work factors into Mitchell’s legacy.

Some claim the “Rest Cure” was the inspiration for Freud’s psychoanalytic couch.

The Dagger’s Deed

By Ken Zurski

In the iconic painting The Death of Caesar (1867), artist Jean-Léon Gérôme’s portrayal of the famous assassination on the Ides of March, 44 B.C., the unfortunate victim, Julius Caesar, is seen crumpled in the foreground while his murderers celebrate by raising their weapons in victory. The only man holding a weapon at his side is Brutus, who is seen with his back turned, walking toward the other celebrants. Perhaps, as history suggests, Brutus dealt the final blow.

He also carries a sword.

This would seem appropriate for the time, since swords were used by Roman soldiers. But the weapon of choice to kill Caesar was not a sword, but a dagger. Brutus all but confirms it in a coin he commissioned after Caesar’s death. On the coin are two daggers with different shaped hilts.

This would seem appropriate for the time, since swords were used by Roman soldiers. But the weapon of choice to kill Caesar was not a sword, but a dagger. Brutus all but confirms it in a coin he commissioned after Caesar’s death. On the coin are two daggers with different shaped hilts.

Presumably, the first dagger belongs to Brutus. The second likely belongs to another assassin.

The shorter daggers make more sense in the killing of Caesar. They were as martial arts experts explain today, “streamlined and remarkably light.” They were also very effective, especially at close range. Plus, a dagger could easily be hidden in a toga and retrieved quickly. The only advantage a sword would carry is the distance between the striker and the intended target. But that was in combat and against another armed assailant.

Caesar was ambushed and received blow after excruciating blow. A brutal and revolting mess, historians explain, and not an easy task.

Caesar was ambushed and received blow after excruciating blow. A brutal and revolting mess, historians explain, and not an easy task.

Instead of celebrating with weapons held high, as Gérôme’s painting suggests, more realistically, the band of conspirators would be hunched over from exhaustion and nausea. Their hands and white garments covered in blood.

“Few felt comfortable talking about it,” author Barry Strauss (The Death of Caesar) writes about the gruesome aftermath of military daggers, “and fewer still doing it.”

When “The Clansman” Came to the White House

By Ken Zurski

On Feb 18 1915, the first screening of a major motion picture took place inside the walls of the White House. President Woodrow Wilson instructed it at the request of a friend Thomas Dixon Jr., author of The Clansman, a radical novel published in 1905, which skewed the Reconstruction era by heroizing the Ku Klux Klan’s efforts against an illicit uprising by former slaves in the South.

Dixon’s book had just become a film version, retitled “The Birth of a Nation.” and directed by D.W. Griffith. Wilson was familiar with the book and its subject matter.

For months, in letters, Dixon had set up the President’s role in the film: “I have an abiding faith that you will write your name with Washington and Jefferson as one of the great creative forces in the development of our Republic,” he wrote. Wilson was flattered, responding: “I want you to know Tom, that I’m pleased to do this little thing for you.” Dixon and Wilson had been law students together at John Hopkins in the 1880’s.

In asking, Dixon was disingenuous at best: “What I told the President was that I would show him the birth of a new art – the launching of the mightiest engine for moulding public opinion in the history of the world.” Dixon was hoping to spread the message of white southern attitudes in the North. This, he explained, was”the real purpose of the film.” In securing a screening, however, Dixon stressed the importance of advancing the medium rather than the content. Wilson took the bait, or as one writer expressed, “fell into a trap.” An assessment, one can argue, was hardly befitting the President’s reputation at the time.

In addition, the President had recently lost his beloved wife to illness. He was in no mood to go – or be seen – in a public theater. So the film came to him.

Dixon set it all up. He along with a projection crew steamed by rail from California to Washington D.C. and lugged twelve reels of film from Union Station to Pennsylvania Avenue. On a chilly February evening the President, along with his family and several cabinet members, viewed the film in the East Room of the White House.

Historical facts get sketchy at this point, especially Wilson’s reaction.

A magazine writer claimed Wilson liked the film enough to contribute an ambiguous quote: “It’s like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it is all terribly true.”

A Wilson biographer, however, disputes these claims, reporting some sixty years later, that the last living person to view the film that night told a vastly different story. Wilson left early before the movie was over, this person recalled, and didn’t utter a word.

In retrospect, what likely happened is this: It was late, the film was long, and Wilson stepped out to retire to bed.

None of this mattered at the time. Just screening the controversial movie in the White House was awkward enough. And regardless of what Wilson did or did not do, having his presence in the flickering light of the projector prompted Dixon and Griffith to proclaim “the presidential seal of approval.”

For Wilson it was another political embarrassment and solidified views by many that the President had policies that were designed to separate rather than mix the races.

When the sharp protests began, Wilson was stuck. He tried to remain indifferent, but that was impossible. The NAACP demanded an explanation. Wilson wrote a few letters, eventually disowned any words attributed to him, and left it at that. He had more important matters to attend to. Specifically, warning Germany of the misuse of submarines in open waters.

In March of 1915, The Birth of a Nation opened to positive reviews and large crowds. The NAACP’s attempt to get the film banned, some professed, failed because the “mostly white” film board ignored it.

Wilson was too busy to care.

Less than three months later, the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania was attacked by German U -boats, killing 124 Americans and ratcheting up awareness for the President to act.

In April 1917, Wilson would declare the U.S. entering the Great War.