Uncategorized

William H. McMasters: The Man who Exposed the Ponzi Scheme

By Ken Zurski

William H. McMasters was all ears.

In 1920, when an Italian immigrant and dreamer named Charles Ponzi walked into the Boston publicist’s office to promote his business, McMasters listened.

Ponzi was using investments to buy postal coupons internationally and reselling them for profit in the U.S. It was totally legal and ingenious.

Ponzi needed to recruit more investors and McMasters was just the person to do it. “I was not averse to having a millionaire as a client,” McMasters later remarked.

McMasters immediately set up an interview at The Boston Post, which was an instant boon for Ponzi. Everyone wanted in. Everyone that is, except McMasters.

The numbers didn’t add up.

Ponzi was recruiting new investors, but far too many. The amount of postal coupons was limited so the promised return was higher than the take. Ponzi knew this, but didn’t tell. McMasters went back to the Post.

Ponzi was recruiting new investors, but far too many. The amount of postal coupons was limited so the promised return was higher than the take. Ponzi knew this, but didn’t tell. McMasters went back to the Post.

The editors were interested in exposing Ponzi, but leery of the process. They didn’t want to get sued. So McMasters wrote an article titled “Declares Ponzi is Now Hopelessly Insolvent.” In it, he explained that Ponzi had invested none of his own money or personally bought any of the stamps.

He used investor money to pay returns, but didn’t know when to stop. Now there were too many investors, too much money owed, and not enough printed stamps to guarantee payouts.

On August 2nd , The Post ran the article and prominently displayed it on the front page.

The next day, the Ponzi scheme was over.

In the end, McMasters found only complacency in his role. While most investors angrily demanded their money back, there were a select few for whom Ponzi’s charm was too persuasive.

They still thought they were getting rich.

Eventually, they blamed McMasters, not Ponzi, for their predicament.

The Fascinating History of John L. Young and the Creation of Miss America

By Ken Zurski

“It’s corny and it’s basic and it’s American” – Bert Parks, television emcee of the Miss America pageant 1955-1979.

In the early part of the 20th century, John L. Young was an Atlantic City entrepreneur who made lots of money, doled out lots of money, and lived quite comfortably off those who spent their hard earned dollars on his wheeling and dealing. That’s no indictment of the man. Young was a dreamer and had the fortitude to dream big and be rewarded. Call it gumption, not greed. It also helped build a truly unique American city.

Born in Absecon, New Jersey in 1853, Young came to Atlantic City as a youthful apprentice looking for work. Adept at carpentry, he helped build things at first including the infamous Lucy the Elephant statue that still greets visitors today.

The labor jobs were steady and the money reasonable, but Young was looking for something more challenging and prosperous. Soon enough, he befriended a retired baker in town who offered Young a chance to make some real dough. The two men pooled their resources and began operating amusements and carnival games along the boardwalk. Eventually they were using profits, not savings, to expand their business.

The Applegate Pier was a good start. They purchased the 600-plus long, two-tiered wooden structure, rehabbed it, and gave it a new name, Ocean Pier, for its proximity to the shoreline. Young built a nine-room Elizabethan- style mansion on the property and fished from the home’s massive open-aired windows. His daily casts became a de facto hit on the Pier. Young would wave to the curious in delight as the huge net was pulled from the depths of the Atlantic and tales of “strange sea creatures below” were told. The crowds dutifully lined up every day to see it. They even gave it a name, “Young’s Big New Haul.”

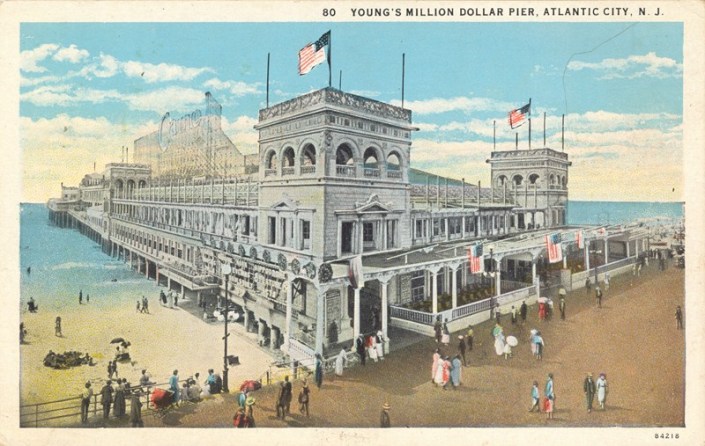

Young had bigger aspirations. He promised to build another pier that would cost “a million dollars,” similar in price back then to a Trump casino today. In 1907, the appropriately titled “Million Dollar Pier,” along with a cavernous building, like a large convention hall, opened its opulent doors. It was everything Young had said it would be and more. Elegantly designed like a castle and reeking of cash, Young spared no expense right down to the elaborately designed oriental rugs and velvety ceiling to floor drapery. It was the perfect place to host parties, special events and distinguished guests, including President William Howard Taft who typical of his reputation – and girth – spent most of the time in the Million’s extended dining hall.

Hotel owners along the boardwalk were pleased. Pricey rooms were always filled to capacity and revenues went up each year. Young had built a showcase of a pier and thousands came every summer to enjoy it. But every year near the end of August there was a foreboding sense that old man winter would soon shut down the piers – and profits.

There was nothing business leaders could do about the seasonal weather. In fact, the beginning of fall is typically a lovely time of year on the Jersey Shore. But Labor Day is traditionally the end of vacation season. In the early 1920’s, by mid-September, the boardwalk and its establishments would become in essence, a ghost town. Something was needed to keep tourists beyond the busy summer season.

A man named Conrad Eckholm, the owner of the local Monticello Hotel, came up with plan. He convinced other business owners to invest in a Fall Frolic, a pageant of sorts filled with silly audience participation events like a wheeled wicker chair parade down the street, called the Rolling Chair. It was so popular, someone suggested they go a step further and put a bevy of beautiful young girls in the chairs. Then an even more ingenious proposal came up. Why not make it a beauty or bathing contest?

A man named Conrad Eckholm, the owner of the local Monticello Hotel, came up with plan. He convinced other business owners to invest in a Fall Frolic, a pageant of sorts filled with silly audience participation events like a wheeled wicker chair parade down the street, called the Rolling Chair. It was so popular, someone suggested they go a step further and put a bevy of beautiful young girls in the chairs. Then an even more ingenious proposal came up. Why not make it a beauty or bathing contest?

Immediately the call went out. Girls were wanted, mostly teenagers and unmarried. They were to submit pictures and if chosen receive an all-expense paid trip to Atlantic City for a week of lighthearted comporting. The winner would get a “brand new wardrobe,” among other things. The entries poured in and by September of 1921, the inaugural pageant was set. Typical of his showmanship and style, John Young offered to host the event at the only place which could do the young ladies justice – The Million Dollar Pier.

The term Miss America came shortly thereafter. The hotel owners suggested the local newspaper sponsor the event as a way of increasing circulation and a reporter for the Atlantic City Press when asked, piped up: “And we will call her Miss America.” Whether he knew the term “Miss United States” had already been used at a beauty pageant in Colorado is not known. Perhaps “Miss America” was his first choice all along. Regardless, the name was perfect. But it didn’t catch on at first. Due to the uncertainty of national acceptance, the pageant was first billed as the “Inter-City Beauty Contest” and for many years the girls were referred to only as “civic beauties.”

The inaugural pageant in 1921 was less than stellar, run on the cheap, and rather bland. The girls frolicked and blended in with large crowds, but got little attention. Even the excitement of the first bathing suit competition was diminished by the fact that everyone was out enjoying the summer-like weather and wearing wet suits like the contestants. The “civic beauties” suits by comparison – covering up skin just above the kneecap – were no more revealing than other more refined patrons on the boardwalk.

The first winner was Margaret Gorman, Miss Washington (D.C.), who was just a week over 15-years-old and still today is the shortest Miss America at 5 foot 1 inch.

Sweet little Margaret apparently dominated the others with her downhome goodness and delightful personality. The judges, under no pretense, had picked sugar over salt, was the consensus.

That’s because the expected front runner, an older, more mature and “flashier” woman named Virginia Lee – who was voted “most charming professional” in a subordinate contest – had all the attributes considered to be a shoo-in at today’s competition.

In 1921, she was hardly in the mix.

Gorman’s surprise victory set the standard for the next several pageants to come. Young girls, exuding charm, cutesy smiles, and solid moral upbringings passed the judges litmus test and scored big. It was the early 1920’s after all. Women’s liberation and feminism was beginning to beckon, but still not widely accepted. Innocence, not independence, won beauty pageants.

The show’s production values, however, went through a major overhaul. It was decided a mascot, symbol, or face of the competition was needed. So King Neptune, God of the Sea, became a pseudo master of ceremonies and followed the ladies to each competition. The man who played the King was reportedly hired because he had the white hair and beard, but was said to be so short-tempered, lookouts were hired to calm any stormy rages.

More contests were added including the “questions round,” an “evening costume party,” and that interminable Rolling Chair parade which lasted two hours and was the highlight of the week. The bathing suit completion, however, continued to be like a day at the beach, with everyone on hand, even the police officers, dressed for a dip in the choppy water.

In 1927, the sixth year, the pageant took an unexpected turn. The girl who won it was an unsuspecting charmer from Illinois, Lois Delander of Joliet, the 17-year-old daughter of a city clerk.

Delander had her high school ballet teacher to thank for encouraging her to compete for a spot locally. The Illinois judges were easily impressed. Lois had intellect and beauty. She was an honor student who studied Latin and was said to be a whiz at music memory games. She was also straight as a ruler. “My lips have never touched coffee or tea,” she told them. Five feet four-and-a-half inches tall and slender for the time, she had sparkling blue eyes and blond “un-bobbed” hair.

“She never smoked,” the papers read.

Delander was soft spoken and quietly motivated. Unlike other contestants, expectations in her own mind were low for the national competition. She didn’t think she had a chance to win and vowed to make it a learning experience instead. “It’s all like a wonderful dream,” she politely told reporters shortly after arriving. “This is the first time I have seen an honest-to-goodness ocean.”

But the excitement didn’t last. She sorely missed home. She missed her family, her school and her classmates. Refusing to quit, however, Delander endured the week with grace, but never considered herself a front runner. On the night of the big announcement she packed her suitcase early and prepared to leave soon after another girl was crowned.

This is not to say that the Delander had a bad week. She was a delight to the judges and as one onlooker described, quite amorously, “looked great in a red and blue swimsuit.” During the question and answer session Delander was asked what she wants to do with her life. “I wish to be an artist,” she proclaimed. The humble response came after nearly half of the other girls said they wanted to be an aviator and “hero,” like Charles Lindbergh, who had just made an unprecedented solo jaunt over the Atlantic in May of that same year. (Apparently Amelia Earhart – who would be lost forever in a solo flight ten years later – wasn’t the only woman who had such lofty aspirations).

Yes, in fact, Lois Delander, Miss Illinois, had a very good week indeed. And although she may not have known it, or cared, she was very much in the running to be the next Miss America. Despite this fact, she packed her bags for an early exit.

As dozens of hopefuls stood on stage, two cards were drawn out of the weirdly symbolic “Golden Apple” shaped container. Five finalists had already been chosen and Delander was one. The five girls stood shoulder-to-shoulder in anticipation as the top two names were read aloud. The first name called was Miss Dallas, she was the runner up. The next name was the winner: Lois Delander.

Surprised, Delander smiled and accepted the award. She clearly didn’t mind the accolades, despite the reservations. “I am so excited that I cannot say much,” she told the press. “I want to thank the pageant committee for the kindness they have shown me. I shall try all through the year to do honor to the title which I bear.” She meant it. That was expected of her. But her next comments came straight from the heart. “Now I must rush home and take up my studies,” she said. “You see I’m a junior in high school and certainly want to finish my course.”

Surprised, Delander smiled and accepted the award. She clearly didn’t mind the accolades, despite the reservations. “I am so excited that I cannot say much,” she told the press. “I want to thank the pageant committee for the kindness they have shown me. I shall try all through the year to do honor to the title which I bear.” She meant it. That was expected of her. But her next comments came straight from the heart. “Now I must rush home and take up my studies,” she said. “You see I’m a junior in high school and certainly want to finish my course.”

And she wasn’t kidding.

The next day, possibly that very evening, Delander and her chaperone mother were steaming by rail back to Joliet. Goodbye Atlantic City.

And, at least initially, goodbye to the Miss America pageant.

After Delander’s victory, the hotel owners association met again and decided by an overwhelming majority to shut the beauty contest down. While their initial reasons for starting such an event was to encourage more traffic through their doors, the clientele was not to their liking. They preferred patrons that spent more money. But that was just their pocketbooks talking. The most glaring concern was in the pageant itself, specifically the girls and their attitudes. Delander, of course, was the exception, but many of the participating “beauties” were stretching their womanly limits, or at least what was expected of them, by pushing away proprietary attitudes and liberating themselves from male seniority. Basically, they were demanding more rights and engaging in mostly male activities – like smoking. As one historian put it, the 1920’s woman was “frank, socially liberated, hedonistic, and reckless.” The friendlier side of Atlantic City, with the beaches, amusements and carnival atmosphere, looked bad because of it, the hotel owners surmised.

The hammer continued to fall in 1927 when the previous year’s winner refused to show up and give away her title because pageant officials wouldn’t pay her an appearance fee. Norma Smallwood from Tulsa was everything pageant officials feared in a beauty queen: a firecracker who could exploit it. After winning the crown, Smallwood reportedly used her status to milk big cash rewards, possibly out earning Babe Ruth by some estimates. She flat out refused to show up in Atlantic City the following year unless she was paid. In quick order, the hotel owners denied the request. Then they set out to stifle any future covetous acts. They started this madness, they clamored, so they could stop it.

So they did.

But America didn’t want it to go away. Delander was a popular winner and beauty pageants across the country were gaining notoriety and more interest. The one in Atlantic City was easily the most recognizable until it abruptly went away.

Lois Delander went back to Joliet after her 1927 victory and was treated like a movie star in her hometown. Naturally, she did her diligent best to live up to the crown’s duties although back then the Miss America title didn’t come with the same prestige and year-round personal obligations as it does today. Still, thanks to the pageant shutdown, she holds the dubious distinction of having the longest reign, five years.

In 1933, the five year hiatus ended. The Miss America pageant was revived by the mayor and City Council of Atlantic City. The hotel owners still refused to support it and watched in delight as a hastily planned and shoddy production almost brought the whole enterprise down for good. The girls were engaging, but beat down physically. Many were handpicked at amusement parks across the country and sent on a whirlwind seven-week promo tour before arriving in New Jersey. By the time the pageant started, they were visibly exhausted. At the Ritz-Carlton where the contestants stayed, sleep deprivation turned into giddy playfulness and some of the more plucky girls were asked to tone it down a bit. The winner, 15-year-old Marian Bergeron of Connecticut, perhaps the most demure of the bunch, later admitted, “If I would have been a little bit older, I think I would have had a ball.”

The pageant went on hiatus for a second time and was revived again in 1935 after just a year off. And again it was a rough go. That year’s winner was a high school dropout named Henrietta Leaver who worked at a dime store and had modest desires. She hoped to find “a full-time job” for her efforts.

The next year, pageant officials made the girls ride bicycles down the pier. Apparently they forget to ask if any of the girls had actually been on a bicycle before. Many didn’t, and fell off. Some cried and vowed to quit but a former contestant got in their faces. Buck it up, was her implication. “I know it’s hard, but you got to learn to take it. It’s part of the contest.”

But it was obvious something needed to change. The next year, in 1937, after a complete revision, the pageant gained its footing and never looked back. For more than six decades it was held in September in Atlantic City as the term “September Girls” took root.

Then in 2006, due to a change in television rights, it was moved to a January date and broadcast from Las Vegas. In 2013, it was moved back to Atlantic City and returned to its usual spot in September (Update: In 2019, the pageant was renamed Miss America 2.o and the 2020 competition will air from the Mohegan Sun Casino in Uncasville, Connecticut on Thursday, December 19th on NBC).

In Atlantic City , the original host venue, the Million Dollar Pier, is gone by name. A half-mile long pier still stands but with a new title, it’s third, The Pier Shops at Caesars Atlantic City, an 80-store shopping mall.

John L. Young’s original structures were damaged by fire and demolished in the early 80’s. In its heyday, however, the palatial showcase was so popular many people gave the man who built it the honor of having his name forever stamped to its lore. Still today, it’s referred to as Young’s Million Dollar Pier or Captain Young’s Million Dollar Pier.

(Sources: There She Is, Miss America: The Politics of Beauty, and Race and in America’s Most Famous Pageant ; There She Is: The Life and Times of Miss America by Frank Deford; Chicago Daily Tribune, September 10,11,12, 1927; Peoria Evening Star Sept 10, 1927.)

The Jamestown Lottery

America’s first lottery winner was a London tailor. His name was Thomas Sharplisse. We know this rather trivial historical fact thanks to a man named John Stow who decided to chronicle English life in in the 16th century. His book Survey of London was released in 1598, a life’s work indeed, since he was dead just seven years later at the age of 80. At the start of the 17th century, however, other diarists picked up the slack, commissioned by King James I, and continued to record anecdotes and life experiences of fellow Londoners. The Stow’s Chronicles is the result. And through it, we know the name Thomas Sharplisse.

Sharplisse was certainly a tailor and from London, but had nothing to do with America except as other Londoners did at the time a passing interest in what was going on overseas. It was after all 1612. The stock holding Virginia Company of London, had funded the first English colony in North America, the struggling James Towne, or more commonly known as Jamestown, named of course in honor of his majesty.

Sharplisse was certainly a tailor and from London, but had nothing to do with America except as other Londoners did at the time a passing interest in what was going on overseas. It was after all 1612. The stock holding Virginia Company of London, had funded the first English colony in North America, the struggling James Towne, or more commonly known as Jamestown, named of course in honor of his majesty.

The newly established settlement (actually it was the second incarnation, the first was James Fort) was reeling from sickness, starvation and occasional attacks by hostile Indians. They were in desperate need for more supplies, but the Virginia Company was broke. So the King approved a lottery, a game of chance really, but also an opportunity for fellow countryman to invest at a time when charitable contributions didn’t exist.

Marketing for the lottery was in the guise of a song:

To London, worthy Gentlelmen,

goe venture there your chaunce:

good lucke standes now in readinesse,

your fortunes to advance

In June of 1612, Sharplisse was among the jostling crowds that gathered in a specially constructed “Lotterie house” near St. Paul’s Church in London to watch tickets drawn in the first Great Standing Lottery. The person who pulled the tickets – in some cases, a child, whose innocence was visible proof of the fairness of the game – dipped his arm into the first drum. Then the second drum was opened and a corresponding slip either a blank or a prize was pulled out. In the words of one contemporary account, the scene was viewed by a gathering of “Knights and esquires, accompanied with sundry grave discreet citizens.” Then the second drum was opened and a corresponding slip either a blank or a prize was pulled out.

Little else is known about Sharplisse except that he spent two-shillings-and-sixpence on a chance. And according to Stow’s Chronicles, Shaprlisse’s ticket was the Grand Prize winner – four thousand crowns in “fayre plate, which was sent to his house in a very stately manner.” It was a fortune at the time. Two Anglican churches took home smaller winnings

After the Virginia Company paid for the prizes, salesman, managers, and other expenses, the remaining revenue covered the cost of shipping people and supplies to Jamestown. It was such a vital resource that Captain John Smith referred to the lottery as “the real and substantial food.” Disappointing, however, was the turn out. Nearly 60-thousand lottery tickets went unsold. Eventually, the crown banned lotteries that benefited Jamestown because of complaints that they were robbing England of money.

More than a century later, citizens of the Thirteen Colonies used lotteries to fund the American Revolutionary War.

(compiled by Ken Zurski. Some text was reprinted from The Lottery Wars: Long Odds, Fast Money, and the Battle Over an American Institution).

Two Minutes

When “A Charlie Brown Christmas” was produced for television in 1965, Peanuts creator Charles Schulz asked for one thing in particular. That the special be about something. Namely, he insisted, it be about the true spirit of Christmas.

Otherwise, he said, “Why bother?

Of course, the spirit of the holiday is exactly what the special is about. Mostly lighthearted and inspirational, it’s highlighted by a moving scene in which the Linus character, blanket in hand, stands on a spotlighted stage and explains the true meaning of Christmas. It includes a biblical passage from the Book of Luke.

His words, like the special itself, has been charming audiences ever since.

Charming, however, was not the word CBS executives used when they first viewed the completed special. They hated it -– or just didn’t get it. The pacing was off, they thought, and the music was different, classical in parts, jazzy in others. “This is probably going to be the last [Peanuts special],” one executive chirped. “But we got it scheduled for next week, so we’ve got to air it.”

Charming, however, was not the word CBS executives used when they first viewed the completed special. They hated it -– or just didn’t get it. The pacing was off, they thought, and the music was different, classical in parts, jazzy in others. “This is probably going to be the last [Peanuts special],” one executive chirped. “But we got it scheduled for next week, so we’ve got to air it.”

The producers were deflated. “We thought we’d ruined Charlie Brown,”one exclaimed.

Until then, the only controversy was whether or not to include the use of a biblical verse in an animated special. Schulz again insisted. “If we don’t do it,” he said “who will.” Coca-Cola, the soft drink giant that sponsored the special, gave their blessing.

Linus’s big scene has reached iconic status now, both in popular culture and religious circles.

“For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord,” Linus recites. “And this shall be a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host, praising God, and saying: ‘Glory to God in the highest, and on Earth, peace and goodwill towards men.

“That’s what Christmas is all about, Charlie Brown.”

Linus’s effective speech is also credited to the child actor who provided the voice. Before the special, Peanuts characters had only been heard in a Ford Commercial. The producer’s wanted them all to be voiced by children. Christopher Shea was only 8 years old at the time. He had the most innocent sounded voice and was tapped for the Linus character. His measured, straightforward reading is considered legendary. “It’s one of the most amazing moments ever in animation, “raved Peter Robbins, the original voice for Charlie Brown. Robbin’s voice was picked for Charlie Brown because it sounded “blah.”

Even though CBS thought it would only run for a year and be forgotten, once it was in the public consciousness, attitudes changed. Instantly, people began talking about it. The next year, the special won a Peabody award and an Emmy for Outstanding Christmas Programming. A lasting tribute to Charles Schulz original vision that it be about something – something with a message.

One scene in particular is still considered, as a producer described it later, as “the most magical two minutes in all of TV animation.”

How a Picture Print of a Steamboat Wreck Ties Into Christmas

By Ken Zurski

On the evening of January 13, 1840, a paddlewheel steamship named the Lexington was halfway through its voyage along the Atlantic coast, a short commuter jaunt between New York City and Stonington, Connecticut, when it caught fire and quickly burned. The fire started in the mast but spread to a large load of cotton bales, which caused a raging inferno that engulfed the entire ship. Many frightened passengers were forced to jump into the frigid water.

By the time a rescue ship, the sloop Merchant, arrived around noon the next day, only a handful of people were found clinging to floating bales or other debris. Nearly all of the 143 on board perished. Only four were found alive, among them three crew members including the ship’s pilot who told rescuers he huddled with others at the bow before it was overcome by fire. He found a bale and was able to sit out of the icy water until help arrived. Only one passenger survived.

The news was devastating to loved ones back in New York where most of the dead resided. The big city newspapers relayed the story in their usual graphic and expressive detail and imagination soared with the shocking details. At the time newspapers were just words on paper with no illustrations. Thanks to the Lexington disaster however that was about to change.

A man named Nathaniel Currier was making lithographs of mostly business products like architectural plans and music manuscripts. Lithography, a process of printing using limestone, grease and water was not new, it had been invented nearly 30 years before Currier, an accomplished lithographer, perfected the craft in Boston and opened a New York shop of his own. But small printing jobs were not profitable and Currier needed to branch out. So he did portrait prints and memorials of the dead and finally made some money. In 1835, he had another idea. He produced a print depicting a true-life disaster. The print needed no more explanation other than the long title that accompanied the scene: Ruins of the Planter’s Hotel, New Orleans, which fell at two O’clock on the Morning of the 15th of May 1835, burying 50 persons, 40 of whom Escaped with their Lives. A picture that showed the news of the day, and produced at a rapid speed too, was striking indeed. It was a huge seller.

A man named Nathaniel Currier was making lithographs of mostly business products like architectural plans and music manuscripts. Lithography, a process of printing using limestone, grease and water was not new, it had been invented nearly 30 years before Currier, an accomplished lithographer, perfected the craft in Boston and opened a New York shop of his own. But small printing jobs were not profitable and Currier needed to branch out. So he did portrait prints and memorials of the dead and finally made some money. In 1835, he had another idea. He produced a print depicting a true-life disaster. The print needed no more explanation other than the long title that accompanied the scene: Ruins of the Planter’s Hotel, New Orleans, which fell at two O’clock on the Morning of the 15th of May 1835, burying 50 persons, 40 of whom Escaped with their Lives. A picture that showed the news of the day, and produced at a rapid speed too, was striking indeed. It was a huge seller.

In 1840, Currier made another disaster print. It too had a long and detailed title: Awful Configuration of the Steamboat Lexington in the Long Island Sound on Monday Evening, January 13. 1840, by which melancholy occurrence over One Hundred Persons Perished. Based on an eyewitness description. the scene was as just as detailed as the newspaper’s words. The wounded steamship is seen burning in the background while a smattering of passengers struggle to stay above the choppy water. Some are on floating debris, others not. One man in a top hat and tails is seen reaching out to save another woman. Tragically, both are doomed.

Currier sold a bunch of the Lexington prints and was soon contacted by the editor of the New York Sun who wanted to put the depiction in the paper. An engraving of another steamboat wreck Home appeared in a competing a New York paper and the Sun was eager to do the same. Currier agreed and the Lexington print was boldly featured in a special edition.

But that’s not why Currier is remembered today.

Experiencing a windfall from the Lexington sales, in 1852, Currier hired James Merritt Ives to be his bookkeeper. Just looking at the two men, the pairing was a physical mismatch. Currier was tall and thin while Ives was short and stout. But the two gelled together. Ives was an artist and quickly streamlined the business with his own and others artistic abilities. In turn, he built up a sizable and profitable inventory. Ives soon became a valuable and dependent part of the team and he and Currier bonded as co-workers and friends. Their eventual partnership In 1857, began the company we know today as Currier and Ives.

Experiencing a windfall from the Lexington sales, in 1852, Currier hired James Merritt Ives to be his bookkeeper. Just looking at the two men, the pairing was a physical mismatch. Currier was tall and thin while Ives was short and stout. But the two gelled together. Ives was an artist and quickly streamlined the business with his own and others artistic abilities. In turn, he built up a sizable and profitable inventory. Ives soon became a valuable and dependent part of the team and he and Currier bonded as co-workers and friends. Their eventual partnership In 1857, began the company we know today as Currier and Ives.

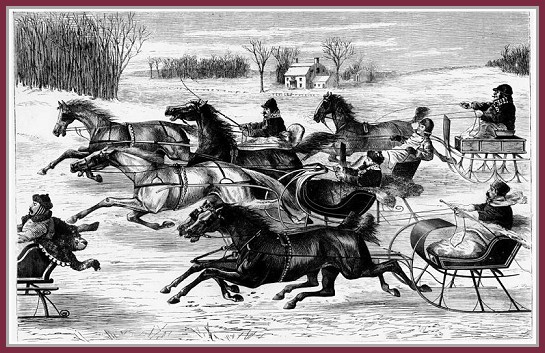

Through the years Currier and Ives issued and sold colored and uncolored prints of every variety, included portraits, city and rural landscapes, trains and ships of note, famous race horses, and historical pictorials like milestones of the Civil War.

Currier and Ives left behind a lifetime of memories and thanks to a a print of the Lexington wreck, forever changed an industry. But their most lasting prints are featured during the holiday season. The folksy scenes of snow and sleigh rides evoke a spirit that is immortalized every year on Christmas cards.

The song Sleigh Ride compares the Currier and Ives prints to other Christmas traditions like chestnuts popping and “pumpkin pie” as having “a happy feeling nothing in the world can buy.”

…It’ll nearly be like a picture print

By Currier and Ives

These wonderful things are the things

We remember all through our lives!

For Currier, however, it all started with a disaster.

Why “Jingle Bells” Is Such An Odd Christmas Song

By Ken Zurski

Besides the wintry scene, snow and sleigh, there isn’t much Christmas spirit in the song “Jingle Bells.” In fact the word Christmas, Santa or anything else holiday related isn’t included in the song at all. It’s about sleigh riding, more or less. More specifically, it’s about sleigh racing. After all, “dashing through the snow” didn’t mean taking a leisurely ride through the countryside. Oh and the bells, the “jingle bells,” they were there for a specific reason too.

Like many traditional Christmas songs, “Jingle Bells” has a strange and fascinating history. Even the first arrangement, which was less upbeat, is different than the one we hear today. Still it has a somewhat festive tone. So much so that early on, it is said, “Jingle Bells” was a used as a party song, featured in drinking establishments, and sung by drunkards who would clink their glasses like bells when the word was mentioned.

This is not too difficult to imagine, since the song was written in the 1850’s, presumably inside a tavern. James Lord Pierpoint, a New Englander is credited with authoring “Jingle Bells.” Some suggest he wrote it in honor of the Thanksgiving feast rather than Christmas, which is unlikely on both counts. After all, how many carols were being written specifically about Thanksgiving?

This is not too difficult to imagine, since the song was written in the 1850’s, presumably inside a tavern. James Lord Pierpoint, a New Englander is credited with authoring “Jingle Bells.” Some suggest he wrote it in honor of the Thanksgiving feast rather than Christmas, which is unlikely on both counts. After all, how many carols were being written specifically about Thanksgiving?

Roger Lee Hall, a New England based music preservationist, does not refute or confirm the Thanksgiving theory only reiterates that Pierpoint may have written the song around or for Thanksgiving, but certainly not about it (although some may argue the song is about traveling). But like the lack of any Christmas themes, the song does not invoke the spirit of food or sharing – only a time and place. So at least the snow fits, especially in the upper east. In this case, Medford, Massachusetts.

It’s also been reported to have been written for the Sunday Choir since Pierpoint was the son of a minister. But as others point out, the song may have been too “racy” for a church, even though by today’s standards it hardly warrants such distinction.

Obviously we don’t hear the “racy” stuff in the modern version of “Jingle Bells,” since many of the original lyrics and several verses are eliminated completely. Only the first and familiar verse of the song is heard and usually repeated several times:

Dashing through the snow

In a one-horse open sleigh

O’er the fields we go

Laughing all the way

Bells on bobtail ring

Making spirits bright

What fun it is to ride and sing

A sleighing song tonight!

In one unfamiliar verse, the rider and his guest, a woman friend named “Fanny Bright,” get upended, or “up sot” (meaning capsized) by a skittish horse:

The horse was lean and lank

Misfortune seemed his lot

He got into a drifted bank

And then we got upsot.

In another verse, a similar mishap is ridiculed by a passerby:

A gent was riding by

In a one-horse open sleigh,

He laughed as there I sprawling lie,

But quickly drove away.

The chorus is then sung similar to what we know it today:

Jingle bells, jingle bells,

Jingle all the way;

Oh! what joy it is to ride

In a one-horse open sleigh.

(The word Joy was eventually replaced by “fun” in later versions.)

The last verse references the races:

Just get a bobtailed bay

Two forty as his speed

Hitch him to an open sleigh

And crack! you’ll take the lead.

Jingle Bells was originally released as “One Horse Open Sleigh” and later changed to “Jingle Bells, or One Horse Open Sleigh.” It was copyrighted in 1859 and first recorded on an Edison Cylinder in 1898. Popular orchestra leaders like Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller did big band renditions of the song in the 1930’s and 40’s and crooner Bing Crosby would record it in 1943. Crosby’s bouncy version with the Andrew Sisters is still considered a traditional favorite.

Today, “Jingle Bells” evokes laughter and joy and is often associated with Santa’s reindeer, so the term has certainly transcended its original purpose. Sleighs made no sound as they glided over the snow and bells were used as a stern warning. Hear jingly bells coming? Get the heck out of the way.

Or else.

Oh, what fun!

Franksgiving

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

In September of 1939, Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a presidential proclamation to move Thanksgiving one week earlier, to November 23, the fourth Thursday of the month, rather than the traditional last Thursday of the month, where it had been observed since the Civil War.

Roosevelt was being pressured by the Retail Dry Goods Association who already reeling from the Great Depression sensed a disaster in holiday sales since Thursday of that year fell on the 30th, the fifth week and final day of November, and late for the start of the shopping season. The business owners went to Commerce Secretary Harry Hopkins who went to Roosevelt. Help out the retailers, Hopkins pleaded. Roosevelt listened. He was trying to save the economy not break it. Thanksgiving would be celebrated one week earlier, he announced.

Apparently, the move was within his presidential powers to suggest since no precedent was set. Thanksgiving, the day, was not federally mandated and the actual date had been moved before. Many states, however, balked at Roosevelt’s plan. Schools were off on Thanksgiving and a host of other events like football games, both at the local and college level, would have to be cancelled or moved. One irate coach threatened to vote “Republican” if Roosevelt interfered with his team’s schedule. Others at the government level were similarly upset. “Merchants or no merchants, I see no reason for changing it,” chirped an official from the opposing state of Massachusetts.

In contrast, Illinois Governor Henry Horner echoed the sentiments of those who may not have agreed with the switch, but dutifully followed orders. “I shall issue a formal proclamation fixing the date of Thanksgiving hoping there will be uniformity in the observance of that important day,” he declared, steadfastly in the president’s corner.

Horner was a Democrat and across the country opinions about the change were similarly split down party lines: 22 states were for it; 23 against and 3 went with both dates.

In jest, Atlantic City Mayor Thomas Taggart, a Republican, dubbed the early date, “Franksgiving.”

Roosevelt made the change official for the succeeding two years, since Thursday would fall late in the calendar both times. But in 1941 The Wall Street Journal released data that showed no change in retail sales in the shopping seasons that Thanksgiving fell earlier. Roosevelt admitted he was wrong, but in hindsight, on the right track. Thanks to the uproar, later that year, Congress approved a joint resolution making Thanksgiving a federal holiday to be held on the fourth Thursday of the month, regardless of how many weeks were in November.

Roosevelt signed it into law.

Baseball’s ‘Eating Champion’ Story is a Little Hard to Swallow, But…

Frank “Ping” Bodie, an Italian-American major league baseball player, once said that he could out eat anyone especially when it came to his favorite dish, pasta. So on April 3 1919, in Florida during a spring training break, Bodie and an ostrich (yes, an ostrich) went head-to-head in an all out, no holds barred, eating contest.

Or did they? That’s left for history to decide.

But it makes for a great story.

As a ballplayer and an outfielder, Bodie was a serviceable player, but a bit of an instigator. He was always up for a good argument and couldn’t help talking up his own merits. ”I could whale the old apple and smack the old onion,” he said about his batting prowess. While playing for a lowly Philadelphia A’s ball club, Bodie claimed there were only two things in the city worth seeing, himself, of course, and the Liberty Bell.

I can “hemstitch the spheroid,” he boasted, apparently talking about the ball.

Despite being a a bit of a braggart, the player’s loved Bodie’s positive attitude. But his expressive candor clashed with managers and he was traded to several teams before ending up with the New York Yankees where his road mate was the irrepressible Babe Ruth. When a reporter asked Bodie what it was like to room with baseball’s larger-than-life boozer, Bodie had the perfect answer. “I room with his suitcase,” he said.

Bodie was born Francesco Stephano (anglicized to Frank Stephen) Pezzello, but most people knew him by his more baseball player sounding nickname, Ping. He claimed “Ping” was from a cousin although many wished to believe it was after the sound of the ball hitting his bat. Bodie was the name of a bustling California silver mining town that his father and uncle lived for a time.

Bodie’s reputation as a big-time eater preceded him.

While in Jacksonville, Florida for spring training, the co-owner of the Yankees, Col T.L “Cap” Huston, heard about an ostrich at the local zoo named Percy who had an insatiable appetite. Huston told Bodie and the challenge was on. Whether it actually happened as reported however is up for debate. The accounts are so wildly embellished that the truth is muddled.

But who was questioning?

Fearing backlash from animal lovers (even those who loved ostrich’s, it seemed), the match was held at a secret location. Bodie reportedly won the contest, but only after Percy, who barely finished an eleventh plate, staggered off and died. Ostrich’s eat a lot, but Percy’s untimely demise was attributed to inadvertently swallowing the timekeeper’s watch. He expired with “sides swelled and bloodshot eyes.” one writer related.

For anyone who believed that, the rest of the story was easy to digest. Bodie finished a twelfth plate of pasta and claimed the self-appointed title of “spaghetti eating champion of the world.”.

The next day, Bodie was in the newspaper for serving up a double play ball in the eighth inning and helping rival Brooklyn Dodgers secure a “slaughter” of the Yankees, 11-2.

There was no mention of the dead bird.