Uncategorized

The Government-Funded, Award-Winning Movie about the Mississippi River

By Ken Zurski

In the summer of 1936, documentary filmmaker Pare Lorentz got the go ahead from the U.S. Government to make a short film about a rather long subject: the Mississippi River.

The film’s job was to throw more support towards the newly appointed Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a government agency created in 1933. The $50,000 budget approved by President Franklin Roosevelt would be used to highlight the environmental and economic concerns along the river, specifically the catastrophic flooding caused by industries like farming and the timber trade that inadvertently sent large amounts of topsoil down the river into the Gulf of Mexico.

Two years earlier, Roosevelt had funded a mildly successful film project titled The Plow That Broke the Plains, also directed by Lorentz, which showed how uncontrolled farming led to the devastating and deadly effects of the Dust Bowl.

It’s fair to say that both Roosevelt and Lorentz had no intentions of making another documentary together. “The Plow” had gone over budget and the government balked, refusing to provide more money and forcing Lorentz to personally foot the bill just to complete the film. At some point however, attitude’s changed. Lorentz saw a map of the Mississippi River and thought it would make a good subject. Roosevelt agreed and gave him a significantly higher budget than “The Plow.” Lorentz was also extended a $30-dollar a day salary.

Immediately Lorentz went to work, filming location after location on the ground and from the air. The crew worked their way up the river from the Gulf of Mexico to Cairo, Illinois, oftentimes working for days on end until principal filming wrapped up in early January 1937. In the end the visuals showed less of the Mississippi and more of the many tributaries. This was as much a part of the river’s history as it was the problem, the film purported.

Reaction to a film being made about the Mississippi River was mixed. Although it’s the most important body of drainage water in the U.S., perhaps even the world, to many, the river itself, was nothing particularly pleasing to look at. The water is drab and dirty looking and along it’s shoreline there is very little rock formations or scenery to enhance it. “If driving, you become aware of its presence miles before you reach it,” author Simon Winchester wrote about the river’s approach. “The landscape falls away. There are swamps on either side, dense hedgerows and copses, miles of small lakes of curious shape.”

Indeed the Mississippi River, especially its midsection, is banked by mostly mud. Even Mark Twain’s flourishes of the river’s attributes from the perspective of a steamboat pilot couldn’t push the attitudes toward its appearance into anything more than just a very long strip of dirt-colored water and sludgy shores.

No question beauty is subjective. Hundreds of quaint cities dot the river’s shoreline and dense tree lines along the Mid to Upper sections provide a multi-colored vista in the Fall.

In St Louis, Missouri, a large man-made monument standing as tall as it is wide (630 feet), greet visitors at the river’s edge; a testament to the men who used the Mississippi’s offshoots to chart the west.

When Lorentz made his movie, however, the idea of a symbol like the “Gateway Arch” was nearly 30 years away. But like the early explorers, Lorentz found significance in its vast network. The tributaries and the people who live along them were the key to its resourcefulness.

The visuals, however, were just part of the overall experience of the 30-minute film. The script, dramatically narrated by an opera singer and actor named Thomas Hardie Chalmers, was not only informational, but poetic too. There’s a good reason why. To promote the project, Lorentz had written two articles for McCall’s magazine. One was wordy and statistical, he thought, so he wrote another version that was more lyrically composed:

From as far East as New York,

Down from the turkey ridges of the Alleghenies

Down from Minnesota, twenty five hundred miles,

The Mississippi River runs to the Gulf.

Carrying every drop of water, that flows down

two-thirds the continent.

Carrying every brook and rill, rivulet and creek,

Carrying all the rivers that run down two-thirds

the continent,

The Mississippi runs to the Gulf of Mexico.

McCall’s chose to publish the latter version and readers responded by writing request letters for copies. Lorentz used the more poetic prose in the film. The music, which incorporated part folk and gospel styles, was written by composer Virgil Thomson.

While the unflinching subject matter certainly raised awareness of the need for more locks and dams, the film is best remembered for it’s cinematic achievements. It went on to win the “Best Documentary” at the 1938 Venice International Film Festival and the script was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in poetry. The noted novelist and poet James Joyce, shortly before his death at age 60, called Lorentz’s script, “the most beautiful prose that I have heard in ten years.”

Before all the artistic accolades rolled in, upon release in October of 1937, the film titled simply “The River” received positive reviews and general widespread acceptance. The first showing at the White House , however, proved less than ideal. While Roosevelt was generally pleased, the president’s Secretary of Agriculture at the time, Henry Wallace, a Midwesterner from Iowa, didn’t know what to think.

“There’s no corn in it,” he said.

The True Spirit of Christmas in A Charlie Brown Christmas

By Ken Zurski

When “A Charlie Brown Christmas” was produced for television in 1965, Peanuts creator Charles Schulz had one specific, but important directive: That the program be about something.

Namely, he insisted, it be about the true spirit of Christmas. Otherwise, he said, “Why bother?

Of course, as we know now, Schulz had his way. Mostly lighthearted and inspirational, “A Charlie Brown Christmas” is punctuated by its infectious original music, a catchy song, and the now iconic symbol of recognition and hopefulness: a seemingly lifeless little tree.

The highlight of the special , however, is a moving scene in which the Linus character, blanket in hand, stands on a spotlighted stage and explains the true meaning of Christmas. It includes a biblical passage from the Book of Luke.

Specifically, Luke 2: 8-14.

Linus recites:

And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid. And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord. And this [shall be] a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

When he is finished with that last line, Linus turns and address someone directly: “That’s what Christmas is all about, Charlie Brown.”

Linus’s words, like the special itself, has been charming audiences ever since.

Charming, however, was not the word CBS executives used when they first viewed the completed special. They hated it -– or just didn’t get it. The pacing was off, they thought, and the music was different: classical in parts, jazzy in others.

They considered scraping it altogether, but were committed to the time slot. Plus, soft drink giant Coca-Cola was sponsoring the program. “This is probably going to be the last [Peanuts special],” one executive chirped. “But we got it scheduled for next week, so we’ve got to air it.”

The producers of the special were deflated by the network’s initial reaction. “We thought we’d ruined Charlie Brown,” one exclaimed. Until then, the only controversy among the writers was whether or not to include the use of an actual biblical verse in an animated special. Behind the scenes, executives thought it might alienate viewers. Schulz again insisted. “If we don’t do it,” he said “who will.” Coca-Cola gave their blessing too. Today the scene is still considered, as one producer described it, as “the most magical two minutes in all of TV animation.”

Linus’s speech is also credited to the child actor who provided the voice. Before the special, Peanuts characters had only been heard in a Ford Commercial. The producers wanted them all to be voiced by children. Christopher Shea was only 8 years old at the time. He had the most innocent sounded voice and was tapped for the Linus character. His measured, straightforward reading is considered legendary. “It’s one of the most amazing moments ever in animation,” raved Peter Robbins, the original voice for Charlie Brown.

Even though CBS thought it would only run for a year and be forgotten, once it was in the public consciousness, attitudes changed. Instantly, people began talking about it. The next year, the special won a Peabody award and an Emmy for Outstanding Christmas Programming.

A lasting tribute to Charles Schulz original vision that it be about something – – something with a message.

There Is An Artist Behind The Iconic ‘Partridge Family’ Bus

By Ken Zurski

Painter Piet Mondrian, born in 1872, was an important leader in the development of modern abstract art and a major exponent of the Dutch abstract art movement known as De Stijl (“The Style”).

Mondrian used the simplest combinations of straight lines, right angles, primary colors, and black, white, and gray in his paintings.

According to one art historian: “The resulting works possess an extreme formal purity that embodies the artist’s spiritual belief in a harmonious cosmos.”

Mondrian who died in 1944 probably would never have imagined that his well-known artistic style would be the inspiration for a popular 1970’s television show called “The Partridge Family.”

Mondrian’s apparent contribution to the show was the exterior paint job of a school bus used by the fictional – but conventional – family of traveling musicians and singers. Mondrian’s style was on full display, seemingly based on one of his paintings.

The bus became the family’s trademark.

From Yahoo Answers: “Although the exterior paint job was arguably based on Mondrian’s Composizione 1921, it was never explained in the show why this middle class family from Southern California chose Dutch proto-modernism exterior paint, rather than the traditional school bus yellow.”

“The Partridge Family” ran on ABC television from September 25, 1970, until it ended on March 23, 1974. It would find an appreciate and loyal audience in syndication for years. Apparently the bus wasn’t so fortunate. As the story goes, after the show ended, the bus was sold several times until it was found abandoned in a parking lot at Lucy’s Tacos In East Los Angeles.

It was reportedly junked in 1987.

(Some text reprinted from Britannica.com and other internet sources)

Ken Zurski’s book “Unremembered: Tales of the Nearly Famous and the Not Quite Forgotten is available now http://a.co/d/hemqBno

Andrew Carnegie and the Million Dollar Question

By Ken Zurski

For a man whose mission it was to relinquish his entire fortune before his death, Andrew Carnegie still had plenty of money left when he passed in 1919 at the age of 83. That’s no indictment of a man who built a massively successful business, became the richest man in America, and devoted his later years to giving it all back. It was a noble thing to do. But Carnegie had made so much capital that even he found it difficult to allocate the funds sufficiently.

So he asked for help.

Carnegie grew up poor in Scotland, came to America, and amassed millions in the steel industry. Along the way, he made just as many enemies as dollars. Like many so-called tycoons of his time, Carnegie was accused of cutthroat practices which sacrificed workers’ rights for the bottom line. In protest, workers revolted.

The Homestead Strike of 1892 was due to a dispute between steel workers at Carnegie’s Homestead, Pennsylvania plant and management which refused to raise workers’ pay despite a windfall in profits. The riot that followed is still one of the bloodiest labor confrontations in history. Ten men were killed in the melee and Carnegie who continued production with nonunion workers, was blamed for the uprising.

Carnegie viewed it differently than the workers. He believed that reducing production costs meant lower prices to consumers. Therefore, he theorized, the community as a whole profited, not the unions. It was a slippery slope. But, many asked, was it worth men dying for?

Carnegie, of course, thought of himself as a benefactor and did not apologize for becoming a wealthy man. When he retired, however, he made it clear that being rich was only relative: “Man must have no idol and the amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry! No idol is more debasing than the worship of money! Whatever I engage in I must push inordinately; therefore should I be careful to choose that life which will be the most elevating in its character.”

Carnegie didn’t hand out money haphazardly. He spent it on things and places that moved him. Among other worthy causes, the most prominent were funds for more schools – especially in low income communities – and the building or expansion of public libraries. In each case, he released the money only after specific demands were met, each one designed to make sure none of it went to waste. Carnegie had final approval.

In 1908, at the age of 72, with millions more left to give, Carnegie wrote a letter to people he admired. It was in effect an offer disguised as a question: “If you had say five or ten million dollars (close to 5-billion today) to put to the best possible use, what would you do with it?” Many of the correspondence were business leaders and some were presidents of institutions already bearing the Carnegie name. Most responded in kind that the money should be used to continue fellowships.

The letters were an indication that the burden of giving away a fortune was weighing heavy on Carnegie’s mind.

“The fact is that after spending about $50-million on libraries, the great cities are generally supplied and I am groping for the next field to cultivate,” Carnegie wrote to President Theodore Roosevelt, looking for inspiration. “You have a hard task as present but the distribution of money judiciously is not without its difficulties also and involves harder work than ever acquisition of wealth did.” Carnegie wrapped up the letter by pointing out the absurdity of that last line. “I could play with that and laugh,” he noted.

In the end, of course, Carnegie left enough money behind to take care of his wife and daughter. His loyal servants and caretakers were awarded pensions and his closest friends received substantial annuities.

Carnegie gave away an estimated $350 million dollars, but for the rest, he had one final request. After the will segments were dived up, nearly $20-million remained in stocks and bonds.

He bequeathed that amount to the Carnegie Corporation organization he proudly founded, and which still exists today.

Meet David Lamar: The Original ‘Wolf of Wall Street’

By Ken Zurski

Con artist and market scalper David Lamar was considered the original “Wolf of Wall Street,” a distinction revived in recent years by a Hollywood movie about a more contemporary stock swindler named Jordan Belfort and a role played by an A-list actor named Leonardo DiCaprio who won a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Belfort in the 2013 film.

The movie plays up the lavish lifestyle and and often times rebellious behavior of Belfort, who spent nearly two years in prison for his role in a fraud scheme. Belfort wrote a book about his exploits, hence the movie, and self-titled it, “The Wolf of Wall Street.”

Leonardo DiCaprio’s blistering performance aside, Jordan Belfort had nothing on the original “Wolf of Wall Street,” David Lamar who in the early part of the 20th century first carried that dubious moniker, assigned by others, and metaphorically referring to a “wolf” as a “rapacious, ferocious, or voracious person.”

Although his successes and failures has been debated over the years, Lamar’s brash, cutthroat tactics are the stuff of legends. For example, Lamar once impersonated a US Senator in hopes of taking the floor and driving down steel prices while he unabashedly shorted the stock.

Lamar was arrested and sent to jail several times and was once accused of having a man beaten who was ready to testify against him. His boldest swindle may have been against a Rockefeller, John Jr. , who spent a million dollars of his wealthy father’s money to buy leather stock, only to watch Lamar sell it off.

On January 12 1934, at the age of 56, Lamar was found dead in a modestly priced hotel room in New York City. In his room police found $138 in cash, a suit a hat, a can, a gold watch and chain, and gold cuff links. That was all which remained from a fortune which at one time was estimated in the millions.

The day after his death, an obituary dispatch appeared in newspapers throughout the country.

It read:

It isn’t so much the loss of wealth in David Lamar’s life which excites curiosity, as it is an appreciation of struggles through which it passed. He had one blinding ambition, and that was huge profits through sly operations on the stock market. What he hoped to gain was not wealth, but power and recognition. He had wealth – this strange man. It didn’t mean a great deal to him. On many occasions, he could have retired and lived lavishly and luxuriously, as he did live when in purple, on a great estate in New Jersey at one time and in a mansion on Fifth Avenue at another. Always his ambition drove him on and when he found his path blocked by legal obstacles, it was charged he was none to scrupulous in cutting his way through them. He divided his time between estate and mansion and jail. We said Lamar must have suffered. The only punishment which could be meted out to him was his own conscience. He was contemptuous and indifferent outwardly to what people said of him, what they thought of him and how they created him. He had his own code and his own rule for living. It was a most bizarre, a most extraordinary one. He took delight in good clothes, in good food, in a cosmopolitan. The mysterious Stock Market operations of the Wolf of Wall Street have been ended by death.

The paper’s vitriolic assessment seems to be on the mark. Several years before his death, even a lawyer meant to represent him, conceding to his client’s reputation.

“The name of David Lamar seems to be anathema,” he said.

The Vapors and ‘Waldo’: There’s a Connection.

By Ken Zurski

In December of 1981, the English power pop group The Vapors released Magnets, the follow-up to their successful debut album New Clear Days which featured the bouncy and ambiguous hit single, “Turning Japanese.”

I’m turning Japanese

I think I’m turning Japanese

I really think so

Although the group had explored heavy themes before on its first album, Magnets was considered even darker. For example, the title song is about the assassination of John F. Kennedy’s, with references to “the motorcade” and the Kennedy children. “Spiders” and “Can’t Talk Anymore” dealt with mental health issues and “Jimmie Jones,” the single, recounted cult leader Jim Jones and the massacre in Jonestown.

They tell me jimmies seen a sign

Says he understand everything

They tell me jimmies got a line

To the man from the ministry

Despite the bleak subject matter, however, the songs were mostly upbeat and catchy, a trademark of the group.

But it didn’t light up the charts.

The album, while positively received, was a commercial flop. The band blamed it on the lack of interest from their new record label, EMI (later changed to Liberty Records), which bought out United Artists shortly after their first release. Due in part to corporate frustration, The Vapors disbanded after Magnets failed to ignite. But today, the album has significance for its inspired cover art, a complex portrait that mirrored the album’s dark undertones.

Martin Handford was the artist.

A London-born illustrator, Handford specialized in drawing large crowds, an inspiration he claims came from playing with toy soldiers as a boy and watching carefully choreographed crowd scenes from old movies.

Handford, who sold insurance to pay bills, was hardly an emerging or successful artist at the time he was asked to design the album cover for Magnets. Drawing upon the theme of the title song, Handford depicted a chaotic crowd scene of an assassination, although you couldn’t tell unless you looked closely. From a reasonable distance, the numerous figures and various colored clothing formed the shape of a human eye.

It was both clever and disturbing.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2057270-1340650452-6500.jpeg.jpg)

For example, at the top right hand corner of the cover, on the roof of a building, there is a man – presumably the assassin – putting away a rifle.

Some of the figures are seen running from the horrific scene unfolding in the “eye’s” iris, while others are curiously drawn to it. But while the cover was certainly an original creation, the artistic style was not.

In fact it has a name: Wimmelbilderbuch.

Wimmelbilderbuch, or “wimmelbook” for short (German for “teeming picture book”) is the term used to describe a book with full spread drawings of busy place’s like a zoo, farm or town square. The page is filled with numerous humans and animals. It’s geared toward children, but adult’s seemed to like it too, especially when an identified object is hidden, making it more like a puzzle than a colorful picture. Several artists incorporated this style, including a Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel, who dates back to the early 16thcentury, and specialized in drawing intricate landscapes and peasant scenes populated by people in various degrees of work or distress. Bruegel’s human figures are mostly depicted as frail and challenged (Fleet Foxes used a Bregel painting The Elder for its 2008 self titled debut album).

Handford’s work wasn’t nearly as depressing as Bruegel’s, but they were similar. Handford purposely drew the Magnets cover with emblematic images, not exactly hidden, but tough to spot, and when found became a personal reward to the viewer – like the tiny assassin on the roof.

This was the inspiration for an idea that eventually became a cultural phenomenon.

Handford created a recurring character he would put in all his drawings: a bespectacled man with wavy brown hair who always wore a red and white striped shirt and stocking cap. His name was Wally.

The trick was trying to find Wally in the crowd.

The concept soon became a contest, then a crave. It led to several best selling books and an iconic, some might say exasperating, new enigma emerged.

“Where’s Wally?” is how they describe it around the world.

In America, it’s called “Where’s Waldo?”

TV’s Groundbreaking Documentary on “Cancer” Had a Face…Dr. Tom Dooley

By Ken Zurski

On April 21 1960, a Thursday, CBS television aired a taped documentary titled “Biography of a Cancer” that for its day, was as timely as it was informative. That’s because in the 1950’s doctors had just begun experimenting with a combination chemotherapy and radiation as treatment. In the public eye, there were just as many questions about its clinical usefulness as there were answers. So the network’s objective was to present a cancer patient and show “truthfully and graphically” the various stages of the disease.

They found the perfect subject in Dr. Thomas A. Dooley.

A lieutenant and rising star in the Navy, Dooley scrapped plans to be an orthopedic surgeon, left the military, and devoted his life to serve those in less fortunate areas of the world. He was profiled by some as a globetrotting playboy, both good looking and successful, who became an “idealistic, crusading servant of the poor and depressed.”

Dooley didn’t care how he was perceived. His mission was clear. But due to this mix of admonition and admiration, his story got notice. Dooley wrote three best-selling books about his humanitarian crusade. One was titled: “Deliver Us From Evil.”

Then he got cancer.

When Dooley agreed to be filmed by CBS he was just about to have surgery on the malignant tumor found near his shoulder.

In August of 1959, the cameras rolled.

Nearly a year later in April, the show aired.

One that day, a newspaper preview titled “Today’s Television Highlights” read like this:

CBS Reports looks at cancer in general and the case of Dr. Tom Dooley in particular on tonight’s “Biography of a Cancer.” Using Dooley as a typical case, we follow his treatment. There are shots of two operations – an exploratory one and a major bit of surgery – which are fairly strong stuff, but important in the complete story. And at the end, there is a conversation between Dooley and cancer researcher Dr. Murray Shear which is an abrasive, no punches-pulled affair. The conclusion, in both Dooley’s case and the broader story in general, is what producer Albert Wasserman terms, “Judiciously Optimistic.” Anyone concerned with cancer should see this, and might be wise for everyone to look in; it dispels a few myths.

One person who didn’t see the TV special airing that night was Tom Dooley. That day, he was in Southeast Asia treating the sick. In fact, Dooley kept a constant travel schedule even after the diagnosis and surgery. His will and determination was an inspiration to the staff of MEDICO, the world-wide health organization Dooley founded. Many of his patients called him “Dr. America,” but his team knew him simply as “Dr. Tom.”

“Walt Whitman, I think, said that it’s not important what you do with the years of your life, but how you use each hour, “ Dooley told the television viewers in the CBS special. “That’s how I want to live.”

Eventually his body weakened, but not his spirit. “I’m not going to quit. I will continue to guide and lead my hospitals until my back, my brain, and my bones collapse,” he said after being admitted for treatment for the last time.

On January 18, 1961, just a month after returning from a mission to Bangkok, Tom Dooley died. He was one day short of his 34th birthday. For all his frantic and tireless efforts, both in front and behind the camera the end was “a quiet, peaceful slipping away,” a friend said about Dooley’s final hours.

At the time of his death, the dedication to his work, and not the brief stint on television, was the focus of numerous articles and memorials.

“Tom Dooley didn’t lose the fight,” one newspaper headline read. Even to the end, “he was fighting for time to carry on his work as long as he could”

The Story of Baseball’s Eating Champion is a Little Hard to Swallow, But Who Cares. It’s Crazy!

By Ken Zurski

Frank “Ping” Bodie, an Italian-American major league baseball player, once said that he could out eat anyone especially when it came to his favorite dish, the kind his mother used to make. So on April 3 1919, in Florida during a spring training break, Bodie proved it by competing in a head-to-head, no holds barred, eating contest against an unlikely opponent – an ostrich! Instead of hot dogs however, Bodie and the bird would eat plates of pasta.

The whole thing sounded absolutely ridiculous and whether it actually happened as reported is doubtful, but it sure makes for an interesting story.

As a ballplayer and an outfielder, Bodie was a serviceable player, but a bit of an instigator. He was always up for a good argument and couldn’t help talking up his own worth. ”I could whale the old apple and smack the old onion,” he said about his batting prowess. While playing for a lowly Philadelphia A’s ball club, Bodie claimed there were only two things in the city worth seeing: himself, of course, and the Liberty Bell.

Despite being a self-professed braggart, the players loved Bodie’s positive attitude. But his expressive candor clashed with managers and he was traded to several teams before ending up with the New York Yankees where his road mate was the irrepressible Babe Ruth. When a reporter asked Bodie what it was like to room with baseball’s larger-than-life boozer, Bodie had the perfect answer. “I room with his suitcase,” he said.

Bodie was born Francesco Stephano (anglicized to Frank Stephen) Pezzello, but most people knew him by his more baseball player sounding nickname, Ping. He claimed “Ping” was from a cousin although many wished to believe it was after the sound of the ball hitting his bat. Bodie was the name of a bustling California silver mining town that his father and uncle lived for a time.

Bodie’s reputation as a big-time eater must have preceded him.

While in Jacksonville, Florida for spring training, the co-owner of the Yankees, Col. T.L “Cap” Huston, heard about an ostrich at the local zoo named Percy who had an insatiable appetite. Huston told Bodie about Percy and the challenge was on. From that point on the accounts of the contest are so wildly embellished that the truth is muddled.

But who was questioning?

Fearing backlash from animal lovers (even those who loved ostrich’s, it seemed), the match was held at a secret location. Bodie reportedly won the contest, but only after Percy, who barely finished an eleventh plate, staggered off and died. Ostrich’s eat a lot, but Percy’s untimely demise was attributed to inadvertently swallowing the timekeeper’s watch. He expired with “sides swelled and bloodshot eyes.” one writer related.

For anyone who believed that, the rest of the story was just as easy to digest. Bodie finished a twelfth plate of pasta and claimed the self-appointed title of “spaghetti eating champion of the world.”.

The next day, Bodie was in the newspaper for serving up a double play ball in the eighth inning and helping rival Brooklyn Dodgers secure a “slaughter” of the Yankees, 11-2.

There was no mention of the eating contest or the supposed dead bird.

The 16th Century ‘Turnspit’ Kitchen Dog

By Ken Zurski

The history of working dogs go way back, centuries in fact to the age of the Vikings, who used the strong, stout breeds for hunting and herding cattle. Some of these breeds, including the Nork or Norwegian Elkhound, remain viable even today.

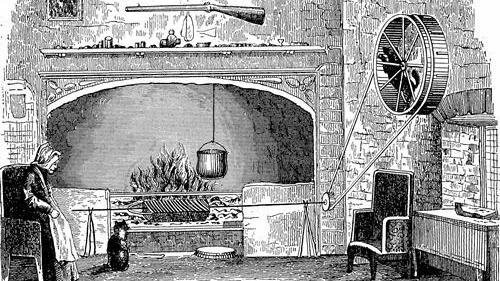

But perhaps no other breed better exemplifies the skill and resiliency of a working dog more than the turnspit, or kitchen dog, whose job it was to turn the spit and cook the meat over a roasting fire.

This was accomplished by a wooden wheel that was mounted on the wall and connected by ropes to the spit in front of the fireplace. The dog would be hoisted on the wheel and begin to run, similar to a hamster in a cage. As the dog ran, the wheel spun, the spit turned, and the meat cooked evenly. To keep the dog from overheating or fainting, the wheel was placed just far enough away from the heat and sparks. And when a dog tired another dog would be ready to take its place.

Until the 16th century when turnspit dogs were introduced, the turning of the cooking spit was the responsibility of a lowest ranking family member, usually the youngest child and almost always a boy. The job was grueling and often resulted in burns, blisters, sores or worse. Dogs were just a better option. Plus they could work longer and would ask for nothing more than to be fed.

Descriptions vary a bit but the overall picture of a “turnspit” paints a dog with short or crooked legs, a heavy head, and dropping ears.

They were low-bodied, strong, sturdy and as one dog historian notes, endured cruel punishment. To train the dog to run faster, oftentimes a burning coal was thrown into the wheel.

In 1750, turnspits were reportedly everywhere in Great Britain. (There are only a few instances that show them in America.) A century later, in 1850, the turnspit breed was nearly gone. The availability of cheaper spit-turning machines, called clock jacks, replaced the turnspits. And since the dogs were considered unappealing and mostly unfriendly, no one kept them as pets. Today the extinct breed is compared to a Welsh Corgi, although its similarities are in looks only.

According to sources, the turnspit dogs would get one day off from the wheel: Sunday.

Not for any spiritual connotation, mind you, but for another useful purpose.

They made good foot warmers in drafty church pews.

“Whiskey,” a taxidermied turnspit dog on display at the Abergavenny Museum in Wales.