Uncategorized

Henry Ford, ‘The Vagabonds,’ and the Birthplace of the Charcoal Briquet

By Ken Zurski

In 1919, car-making giant Henry Ford had been eyeing a significant tract of land on the far western portion of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan known as Iron Mountain. Ford’s cousin, Minnie, to whom he was very close, lived there along with her husband E.G. Kingsford. Thanks to his wife’s family connections, Kingsford ran a successful timber business and owned several car dealerships in the area.

Kingsford, of course, is a name synonymous with charcoal briquets, but the backstory has just as much to do with Ford’s keen business sense.

Here’s why:

At the time, Ford had begun wrestling control from his stockholders and purchasing raw materials to be used in making his vehicles. Anything to make his car making process more efficient, he implied. Kingsford had a beat on something Ford desperately sought. So Ford invited Kingsford to go camping with him. To talk business, he explained.

Ford had been making headlines across the country, not just for making cars, but for using one too. Ford went on road trips. The press dubbed it, “auto-camping,” because Ford along with his three close friends, who called themselves “the vagabonds” would travel by automobile during the day then set camps at night. Ford’s camping companions were no slouches. They included Harvey Firestone, the tire company founder; John Burroughs, the conservationist; and inventor Thomas Edison. Their journeys included a jaunt through the Florida Everglades and treks across mountainous regions in West Virginia and New England. Their first trip to the Adirondacks in 1918 was so satisfying they all agreed to make a trip to a new destination every year.

The trips were well-organized, well-stocked and oftentimes well-staffed with cooks and a cleaning crew. Like true campers, though, the formidable men did sleep on folding cots in a ten-by ten canvas tent. Burroughs, in his 80’s and the oldest by age of the four (Ford was in his 50’s), chronicled most of the adventures. He marveled at their resiliency. “Mr Ford seizes an ax and swings it vigorously til there is enough wood for the campfire,” he wrote.

Each year newspapers ran features of “the vagabonds” latest adventure and newsreels of their exploits were shown in movie theaters throughout the country. After all these were prominent American inventors and role models to some like Edison and Ford, who despite their gray hair, and unabashed preference to wear business attire – tight collars, three piece suits and ties – even on the retreats, were “roughing it,” so to speak, in the great outdoors. The papers couldn’t hide the obvious irony of it all. “Millions of Dollars Worth of Brains Off on Vacation,” the headlines blared. Even President Warren G. Harding joined the men briefly for one excursion.

Kingsford must have been pleased and a certainly flattered by Ford’s invitation to join “the vagabonds” in Green Island, New York, a popular fishing spot near Edison’s Machine Works company. Ford had a purpose. He needed land. Specifically, he needed land with timber on it. Nearly one-million board feet a day was used to manufacture the popular Model T’s, whose chassis were made mostly of wood.

Kingsford convinced Ford to buy some flat land near the Menominee River and build a wood distillation plant. Ford heeded his advice and went even further. He would build the plant and an electric dam nearby to power it. Ford hated to waste anything and in the wood distillation process there was always a lot of waste, specifically wood chip ash, or rough charcoal. So Ford had an idea. He mixed the crushed charcoal with a potato starch glue and pressed the blackened goo into a pillow-shaped briquette. When lit, it burned white ash and produced searing heat, but little or no flame.

Ford was not the first person to come up with the idea of charcoal in a briquet. That honor goes to a man named Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer from Philadelphia who patented the idea in 1897. Ford, however, was the first to commercially market it. He advertised the new product as “a fuel of a hundred uses” and perfect for “barbecues, picnics, hotels. restaurants, ships, clubs, homes, railroads, trucks, foundries, tinsmiths, meat smoking, and tobacco curing.” For home use, it was less dangerous than a traditional wood fire, but just as useful. “Briquette fire alone is enough to take the chill off a room,” the instructions informed. “Absence of sparks eliminates this menace to rugs, floors and clothing.”

Ford’s put his signature logo on the charcoal briquettes bags and sold them exclusively at his many car dealerships. When Ford died in 1947, the charcoal business was phased out. Henry Ford II took over and sold the chemical operation to local business men who changed the name to reflect its local heritage: Kingsford Chemical Company. By that time, Kingsford was not just a person, but a city. Thanks to the economical success of Ford’s wood, parts and charcoal plant, the land used to build the original timber business was named in honor of its first industrialist.

His story is rarely told. In short, Kingsford was born in Woodstock, Ontario and moved to Michigan as a young boy. He lived on his parents farm in Fremont before becoming a timber agent and moving to Marquette in the Upper Peninsula. In 1892, Kingsford married Mary Francis “Minnie” Flaherty, Henry Ford’s cousin. Several years later, he signed a contract to become a Ford sales agent in Marquette and eventually moved to Iron Mountain where he bought tracks of land for timber and opened several Ford dealerships. When Ford called to discuss the possibility of using the massive timber resource for his car making, Kingsford answered.

Eventually, the once uncharted land, about five square miles total, was named Kingsford, Michigan.

Despite the distinction, however, Ford, not Kingsford, is prominently associated with the town’s history. Ford was responsible for putting up the large factory, employing hundreds of workers, and building modern houses for the workers and their families to live. Within just one year, in 1920, the population of Kingsford blossomed from a mere 40 residents to nearly 3,000, creating a town out of an enterprise, thanks to Henry Ford.

By the time Ford’s imprint left in 1950, the town of Kingsford was established enough to persevere, although the plant’s closing was a blow economically. After the parts plant it’s doors in the 1960’s, the charcoal business also left; moving operations to Louisville, Kentucky.

Ford’s name is still displayed on several establishments in town: Ford Airport, Ford Hospital and Ford Park are just a few examples. In a a publication honoring the city’s 75th Jubilee, Kingsford is refereed to as “The Town that Ford Built.”

Some might say that’s a slight to Kingsford, the man, who by association convinced Ford to venture out to the remote section of the Upper Peninsula, ultimately invest in some land, and put a city on the map. Today, you have to go to Kingsford, Michigan to get the full story. You’ll see. Ford still gets the credit.

But when it comes to charcoal, we all know whose name is on that big blue and white bag.

Walt Disney, the Early Shorts, and ‘Oswald the Lucky Rabbit’

By Ken Zurski

His face was round, his body rubbery. He laughed. He cried. For kicks, he could take off his long supple ears and put them back on again. His name was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and he was the first major animated character created by a man who would later become – and still is – one of the most enduring public figures of our time: Walt Disney.

Walter Elias Disney was just in his twenties when the idea for Oswald came along. A gifted graphic artist from the Midwest, Disney had spent some time overseas during World War I as an ambulance driver and returned to the U.S. to work for a commercial arts company in Kansas City, Missouri. Disney had a knack for business. He partnered with a local artist named Ub Iwerks and together they formed their own company, Iwerks –Disney (switching the name from their first choice of Disney- Iwerks because it sounded too much like a doctor’s office: “eye works”).

They dabbled in animation and soon were making shorts, basically live action films mixed with animated characters. They made a slew of little comedies called Lafflets under the name Laugh-O-Grams. It was a tough sell. Studios backed out of contracts and various offers fell flat.

Disney never gave up and soon they had a series called Alice the Peacemaker based loosely on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Alice was different and seemingly better. They used a new technique of animation, more fluid with fewer cuts and longer stretches of action. Alice, the heroine of the series, was a live person, but the star of the comedies was an animated cat named Julius. The distributor of the Alice shorts, an influential woman named Margret Winkler, had suggested the idea. “Use a cat wherever possible,” she told Disney, “and don’t be afraid to let him do ridiculous things.” Disney and Iwerks let the antics fly, mostly through their feline co-star.

When Alice ran its course and Disney was thinking of another series and character, he wanted it to be an animal. But not a cat, he thought, there were already too many. That’s when a rabbit came to mind. A rabbit he named Oswald.

It was a shaky start. The first Oswald short, Poor Papa, was controversial even by today’s standards. In it, Oswald is overwhelmed by an army – or air force, if you will – of storks each carrying a baby bunny and dropping the poor infants one right after the other upon Oswald’s home. Oswald was after all a rabbit and, well, rabbits have a reputation for being prodigious procreators. But this onslaught of newborns, hundreds it seemed, was just too much for the budding new father. Oswald’s frustration turns to anger and soon he brandishes a shotgun and starts shooting the babies, one by one, out of the sky like an arcade game. The storks in turn fire back using the babies as weapons.

Pretty heady stuff even for the 1920’s, but it wasn’t the subject matter that bothered the head of Winkler productions, a man named Charles Mintz. It was the clunky animation, repetition of action, no storyline, and a lack of character development that drew his ire.

Disney and Iwerks went back to work and undertook changes that made Oswald more likable – and funnier. They made more shorts and audiences began to respond. Oswald the Lucky Rabbit caught on. Soon, Oswald’s likeness was appearing on candy bars and other novelties.

Disney finally had a hit. But the reality of success was met with sudden disappointment. Walt had signed only a one-year contract, now under the Universal banner, and run by Winkler’s former head Mintz. The contract was up and Mintz played hardball. He wanted to change or move animators to Universal and put the artistic side completely in the hands of the studio. Walt was asked to join up, but refused. He still wanted full control. Seeing an inevitable shift, many of Disney’s loyal animators jumped ship, but Walt’s close friend and partner Ub Iwerks stayed on. Oswald was gone, but the prospects of a new company run exclusively by Walt were at hand.

Under Universal’s rule, Oswald’s popularity waned. Mintz eventually gave the series to cartoonist Walter Lantz who later found success in another popular character, a bird, named Woody Woodpecker. Oswald dragged on for years, as cartoons often do, and was eventually dropped.

Disney, meanwhile, needed a new star.

Here’s where it gets better for Walt. In early 1928, Disney was attending meetings in New York when he got word that his contract with Universal would not be renewed. Although he later said it didn’t bother him, a friend described his mood as that of “a raging lion.” Disney soon boarded a train and steamed back west. As the story goes, during the long trip, Disney got out a sketch pad and pencil. He started thinking about a tiny mouse he had once befriended at his old office in Kansas City. He had an idea. He began to draw a character that looked a lot like Oswald only with shorter rounded ears and a long thin tail.

Steamboat Willie starring Mickey Mouse debuted later that year.

John L. Young and The Million Dollar Pier

By Ken Zurski

John L. Young was a big deal in the early 20th century. The Atlantic City, New Jersey entrepreneur made lots of money, doled out lots of money, and lived quite comfortably off those who spent their hard earned dollars on his wheeling and dealing. Call it gumption, not greed. Young was a dreamer and had the fortitude to dream big and be rewarded. It also helped build a truly unique american city and in retrospect the beginning of a uniquely American institution, too.

Born in Absecon, New Jersey in 1853, Young came to Atlantic City as a youthful apprentice looking for work. Adept at carpentry, he helped build things at first including the infamous Lucy the Elephant statue that still greets visitors today.

The labor jobs were steady and the money reasonable, but Young was looking for something more challenging – and prosperous. Soon enough, he befriended a retired baker in town who offered Young a chance to make some real dough. The two men pooled their resources and began operating amusements and carnival games along the boardwalk. Eventually they were using profits, not savings, to expand their business.

The Applegate Pier was a good start. They purchased the 600-plus long, two-tiered wooden structure, rehabbed it, and gave it a new name, Ocean Pier, for its proximity to the shoreline. Young built a nine-room Elizabethan- style mansion on the property and fished from the home’s massive open-aired windows. His daily “casts” became a de facto hit on the Pier. Young would wave to the curious in delight as the huge net was pulled from the depths of the Atlantic and tales of “strange sea creatures below” were told. The crowds dutifully lined up every day to see it. They even gave it a name, “Young’s Big New Haul.”

But Young had even bigger aspirations. He promised to build another pier that would cost “a million dollars.” In 1907, the appropriately titled “Million Dollar Pier,” along with a cavernous building, like a large convention hall, opened its opulent doors. It was everything Young had said it would be and more, elegantly designed like a castle and reeking of cash.

Young spared no expense right down to the elaborately designed oriental rugs and velvety ceiling to floor drapery. It was the perfect place to host parties, special events and distinguished guests, including President William Howard Taft who typical of his reputation – and size – spent most of the time in the Million’s extended dining hall. “The pier itself was a glorious profusion of pennants, towers, and elongated galleries, wrote Jim, Waltzer of the Atlantic City Weekly. “It attracted stars, statesmen, and, of course, paying customers.”

Hotel owners along the boardwalk were pleased. Pricey rooms were always filled to capacity and revenues went up each year. Young had built a showcase of a pier and thousands came every summer to enjoy it. But every year near the end of August there was a foreboding sense that old man winter would soon shut down the piers – and profits.

There was nothing business leaders could do about the seasonal weather. In fact, the beginning of fall is typically a lovely time of year on the Jersey Shore. But the start of the school year and Labor Day is traditionally the end of vacation season. In the early 1920’s, by mid-September, the boardwalk and its establishments would become in essence, a ghost town. Something was needed to keep tourists beyond the busy summer season.

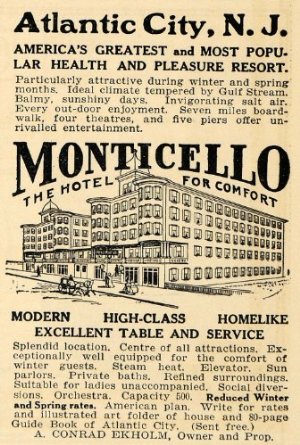

A man named Conrad Eckholm, the owner of the local Monticello Hotel, came up with a plan. He convinced other business owners to invest in a Fall Frolic, a pageant of sorts filled with silly audience participation events like a wheeled wicker chair parade down the street, called the Rolling Chair. It was so popular, someone suggested they go a step further and put a bevy of beautiful young girls in the chairs. Then an even more ingenious proposal came up. Why not make it a beauty or bathing contest?

Immediately the call went out. Girls were wanted, mostly teenagers and unmarried. They were to submit pictures and if chosen receive an all-expense paid trip to Atlantic City for a week of lighthearted comporting. The winner would get a “brand new wardrobe,” among other things. The entries poured in and by September of 1921, the inaugural pageant soon to become known as “Miss America” was set.

Typical of his showmanship and style, John Young offered to host the event at the only place which could do the young ladies justice – The Million Dollar Pier.

In Atlantic City today, the Million Dollar Pier, is even gone by name. A newer half-mile long pier still stands but with a new title, it’s third, The Pier Shops at Caesars Atlantic City, an 80-store shopping mall.

The original Million Dollar Pier was demolished in the 1960’s.

A Telegraph Operator’s Titanic Response

By Ken Zurski

Late in the evening, April 14, 1912, on a passenger liner in the Atlantic Ocean, telegraph operator Harold Cottam was getting ready for bed. Cottam was the only wirelessman on board the RMS Carpathia bound for Gibraltar by way of New York. The day had been busy as usual and Cottam was looking forward to shutting it down for the night.

The radio, however, remained open.

“Why?” he was asked later in an inquiry.

“I was receiving news from Cape Cod.” he replied. “I was looking out for the Parisian, to confirm a previous communication with the Parisian. I had just called the Parisian and was waiting for a reply, if there was one.”

At this point, Cottam might have been asked about allegations, based on the late hour, that he was listening to Cape Race in Newfoundland for English football scores, clearly against regulations. But under oath, he said it was only the Marconi base at Cape Cod he was monitoring. Cottam says he kept the telephone on his head with the hope that before he got into bed, a message would be confirmed.

“So, you were waiting for an acknowledgement [from the Parisian]?”

“Yes, sir,” Cottam conferred

Cottam says he received no word from the Parisian, but did get a late transmission from Cape Cod to relay a message to another ship steaming to New York from England’s Southampton shore. The large ocean liner had been sailing for several days and the messages – mostly personal correspondence for passengers – did not go through. Perhaps Cottam, who was closer, would have better luck. “I was taking the messages down with the hope of re-transmitting them the following morning,” Cottam said. But Cottam didn’t wait until morning. He immediately tried to reach the ship.

“And you did it of your own accord?”

“I did it of my own free will,” he replied

Cottam said he sat down at the telegraph desk and tapped out these words: “From the Carpathia to the Titanic are you aware of a batch of messages for you” The reply came quickly. It wasn’t what Cottam was expecting: CQ followed by D, a general distress call.

“And what did it mean?” he was asked.

“Come at once,” Cottam explained,

“come at once.”

All Hail the Mechanical Pencil and its Lasting Legacy

By Ken Zurski

In 1822 the first patent for a lead pencil that needed no sharpening was granted to two British men, Sampson Mordan and Isaac Hawkins. A silversmith by trade, Mordan eventually bought out his partner and manufactured the new pencils which were made of silver and used a mechanism that continuously propelled the lead forward with each use. When the lead ran out, it was easily replaced.

While Mordan may have marketed and sold the product as his own, the idea for a mechanical pencil was not a new one. In fact, its roots date back to the late 18th century when a refillable-type pencil was used by sailors on the HMS Pandora, a Royal Navy ship that sank on the outer Great Barrier Reef and whose artifacts, including the predated writing utensil, were found in its wreckage.

Mordan’s design notwithstanding, between 1822 and 1874, nearly 160 patents for mechanical pencils were submitted that included the first spring and twist feeds.

Then in 1915, a 21-year old factory worker from Japan named Hayakawa Tokuji designed a more practical housing made of metal and called it the “Ever-Ready Sharp.”

Simultaneously in America, Charles Keeran, an Illinois businessman and inventor, created his own ratcheted-based pencil he similarly called Eversharp.

Keeran claimed individuality and test marketed his product in department stores before submitting a patent. The pencil was so popular that Keeran had trouble keeping up with orders. So to help with production, he partnered with the Wahl Machine company out of Chicago. It was not a good fit. Keeran lost most of his stock holdings in a bad deal and was eventually forced out even though his pencils were making millions annually in sales.

“Built for hard work. Put it on your working force. With no wasteful whittling, no loss of time, it is positive economy,” the ads for the Wahl Eversharp touted. “It’s made with the precision of a wrench.”

Around the same time, in Japan, Tokuji’s factory was leveled by an earthquake.

Tokuji lost nearly everything in the disaster including some members of his family. So to start anew and settle debts he sold the business, began making radios instead, and founded a company that turned into one of the largest manufacturers of electronic equipment in the world.

He named it Sharp after the pencils.

The Overtly Sensual Life of ‘The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up’

By Ken Zurski

In 1906, at the age of 21, Pauline Chase was asked to portray Peter Pan on stage, a play about “the boy who wouldn’t grow up,” and a title role that had been played by only two people before her – both female. Chase continued that trend and in the process became the face of the role too. Even today based on the number of performances – nearly an estimated 1400 – Chase is arguably the most popular actress ever to play the boy Peter.

And you probably have never heard of her.

But in the early 20th century thanks to her continuing success in the play, Chase became an instant celebrity. Not for the innocence of the character she portrayed, in fact, quite the opposite. Chase was a bit of a jezebel in real life. “She certainly knew what she wanted from a man, and it wasn’t a good heart or worthy talent,” wrote author Gavin Mortimer in his book Chasing Icarus about the early aviators (more on that in moment).

And men, well, they couldn’t resist her desirability either. Their pursuance, however, came with stipulations. “I’ve no time to waste on duffers with no position or money,” Chase once told a reporter, firmly setting down the ground rules. Even her performances were sarcastically criticized by one glaring – more like obvious – diversion. Her strikingly good looks. “Distractingly pretty.” is how the Chicago Tribune put it.

Enter Charles Frohman. The world renowned theater producer recognized Chase’s talents early on when she was just a teenager. He promoted his new find and kept a close watch on her like a daughter. It was Frohman who suggested to James M. Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, or The Boy who wouldn’t Grow Up, that Chase take over the title role after another actress Cecelia Loftus got sick. Barrie already knew Chase, who was one of the Lost Boys in the London production. But playing the high-flying main character was a different matter.

“Barrie and I are coming down to see you act,” Frohman wrote Chase before the show,”and if we like you well enough, I will send you back a sheet with a cross mark on it.” After the performance, Chase received a piece of paper. It had a cross mark on it.

Frohman was devoted to Chase, his star in the making, and although rumored, their relationship was never sexual. Soon after his untimely death in 1915 along with more than a thousand other unfortunate souls aboard the ill-fated RMS Lusitania, it was discovered that Frohman had a longtime live-in companion, Charles Dillingham, another theater producer.

Robert Falcon Scott, the debonair British naval officer and explorer was another who reportedly had a close friendship with the magnetic Chase. The connection was influenced by Scott’s association with Barrie. “I never could show you how much your friendship meant to me,” Scott wrote to his author friend, “for you had much to give and I nothing.” Perhaps that gift was Chase. Scott reportedly went to see a production of Peter Pan in 1906 the year Chase took over the role. Was it just flirtation or something more? No one knows for sure. Scott’s affections toward Chase apparently ended in 1909 when he married the cosmopolitan and socialite Kathleen Bruce. Barrie reportedly penned a letter to Chase breaking the news. “Capt. Scott wrote to me that he is to be married to Miss Bruce soon. So there!”

In 1912, Scott perished along with his crew in Antarctica.

Claude Grahame-White was another interest of Chase’s. Perhaps the most desired bachelor in all of England at the time, Grahame-White made the ladies swoon over his athletic six-foot frame and naturally good looks. As one of the early aviation pilots, Grahame-White became instantly famous for being handsome, dashing and adventurous. He mixed all of these traits to great advantage.

How Chase and Grahame-White met is unknown, but they were reportedly friendly for many years before becoming lovers. Grahame-White attended multiple performances of Peter Pan and would invite the pretty actress aboard his Farman biplane for joy rides.

Chase was charmed by her latest admirer. Grahame-White had all the attributes she was looking for: money and status. Their courtship, engagement and eventual marriage in 1910 was the stuff tabloid’s are made of. But it didn’t last. The next year Chase and Grahame-White drifted apart. The industrious flyer had spent all his assets on expensive business ventures and earnings from his flying career was waning. Sparked by a sudden fear of dying in a plane crash – something that was happening quite frequently on the show circuit – Grahame-White decided to quit flying altogether and forgo the riches that came with it. Chase was typically frank when she told a reporter, “Mr. Grahame-White could not compensate me from my retirement from the stage.” They separated and divorced.

Chase ended her seven year reign as Peter Pan in 1913 and never appeared on stage again. Her sexual exploits, true or not, continued to make headlines, especially the extensive string of male suitors. In addition to Capt. Scott and Grahame-White, the list also included a nameless American millionaire, an English auto manufacturer, and even James M. Barrie, the author who created the character that changed her life.

Chase eventually married into a wealthy British family, had three children, and died at the age of 76.

“The boy who wouldn’t grow up” was her most famous and final role.

(Sources: Chasing Icarus by Gavin Mortimer; various internet sites)

The Unusual and Anxious Inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes

By Ken Zurski

On the evening of March 3, 1877, a Saturday, President Ulysses S. Grant, the popular Civil War general turned commander-in-chief, who had served two terms and was only days from leaving office, invited several friends to the White House for a private dinner.

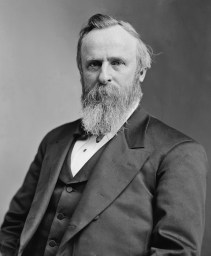

On the guest list that night was the man who would succeed Grant as president, Rutherford B. Hayes.

Hayes had just been declared the winner of the contentious 1876 election over Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, a Yale educated lawyer and governor of New York, who some say beat Hayes outright, but lost the bitter debate that followed. On November 9, the day after the general election, tallies showed that Tilden won the popular vote and picked up more electoral votes than Hayes at 184 to 165, with 20 still undecided.

In question were the southern states where Republicans accused the Democrats of widespread voter fraud, specifically the suppression of the black vote. No winner was declared and nothing was resolved. By the end of 1876, the Centennial year, a nation was left hanging by an undecided outcome. Grant was convinced that if the blacks in the south had been allowed to vote as law permitted, Hayes would have won easily.

In January 1877, thanks to a measure passed by Congress and approved by Grant, the election was put in the hands of an appointed committee, made up of a combined fifteen lawmakers and Supreme Court justices. Party membership was evenly divided between the ten congressmen. As for the five justices chosen, four were considered partisan – two Republicans and two Democrats – and one independent, presumably the deciding vote. But David Davis, the independent from Illinois, had just been elected to the Senate and would be leaving his associate judgeship post soon. In his stead, another justice Joseph Bradley, who was considered to be most politically neutral of the remaining judges, took his place on the committee.

In a decision known as The Compromise of 1877, Bradley voted in favor of the Republicans and tipped the balance to Hayes awarding him the presidency by one electoral vote. The so called “compromise” was an agreement by Republicans to pull the last federal troops out of southern states and effectively end the Reconstruction era.

So on Saturday, March 3, just days before he was set to relinquish the office, President Grant invited Hayes to the White House along with some other close friends for a welcoming dinner.

It turned out to be significantly more.

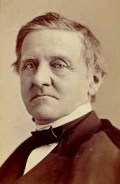

Also in attendance that night was Chief Justice Morrison Waite, whom Grant had appointed to the high court in 1874 and was eventually nominated to replace longstanding Chief Justice Salmon Chase, who died the year before. The day of the inauguration was by law scheduled for March 4. That year, the date fell on a Sunday. Hayes refused to be inaugurated on the Sabbath and it was changed to the following day, Monday, March 5, instead.

Grant was worried Tilden, still reeling from the committee’s decision, might stir up an angry base which had hinted at a government coup. Rumors persisted that Tilden, in an unprecedented act of defiance, would take the oath of office in New York on the actual inauguration date, March 4, and in effect protest the legality of Hayes appointment.

So Grant requested Hayes take the oath that night in private. That way if Tilden tried to undermine the process, at least the Republicans could counter that Hayes was already in charge. Hayes agreed and the three men along with a few witnesses quietly exited to the Red Room where Hayes raised his right hand, read the oath, and was sworn in as the 19th President of the United States.

As it turned out, Grant’s fears about Tilden were unwarranted. Two days later, without incident, Hayes repeated the words on the east portico of the Capitol.

The private ceremony was not a secret, although it’s significance was not easily defined. In 1887, Adam Badeau, a close adviser of Grant’s, tried to give it more clarity in his book Grant in Peace: Appomattox to Mount Gregor. It is perhaps the first time the Tilden angle is revealed. Although he doesn’t state it directly, Badeau was likely in the room that night.

“It was a critical moment in the history of the country,” he clearly overstated.

Recent attitudes toward the 1876 elections paint a different picture. The decision to swear in the President-elect a few days early is either downplayed as political ostentation, based on an imminent threat to Hayes’s life, or attributed directly to Grant’s eagerness to leave the presidency.

No doubt, Grant was counting down the days.

Even though the country was still in a free fall from the war and Reconstruction was murky at best, no one was happier to get out of the Oval Office more than the former General, who planned a European tour with his wife Julia after his second term was over, which they satisfied by leaving the United States in May of 1877 and traveling abroad for more than a year. “I was never as happy in my life as the day I left the White House,” Grant wrote a friend. “I felt like a boy getting out of school.”

Hayes kept a promise to serve only one term. In the 1880 presidential election, Republican James Garfield won a close but undisputed contest over Democratic rival Wilfred Scott Hancock.

(Sources: Grant in Peace: Appomattox to Mount Gregor by Adam Badeau; Ulysses S. Grant: Soldier & President by Geoffrey Perret; The Man who Saved the Union by H.W. Brands)

How the Muddy Mississippi River Became a Cinematic and Poetic Masterwork

By Ken Zurski

In the summer of 1936, documentary filmmaker Pare Lorentz got the go ahead from the U.S. Government to make a short film about a rather long and tendentious subject: the Mississippi River.

Of course, there was a purpose to it all. The $50,000 budget approved by President Franklin Roosevelt would highlight the environmental and economic concerns along the river, specifically the massive and catastrophic flooding caused by industries like farming and the timber trade that inadvertently sent large amounts of topsoil down the river into the Gulf of Mexico. The film’s job was to throw more support towards the newly appointed Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a government agency created in 1933 to provide resources to the Tennessee Valley for among other things, flood control.

Two years earlier, Roosevelt had funded a mildly successful film project titled The Plow That Broke the Plains, also directed by Lorentz, which showed how uncontrolled farming led to the devastating and deadly effects of the Dust Bowl.

It’s fair to say that both Roosevelt and Lorentz had no intentions of making another documentary together. “The Plow” had gone over budget and the government balked, refusing to provide more money and forcing Lorentz to personally foot the bill just to complete the film. At some point however, attitude’s changed. Lorentz saw a map of the Mississippi River and thought it would make a good subject. Roosevelt agreed and gave him a significantly higher budget than “The Plow.” Lorentz was also extended a $30-dollar a day salary.

Immediately Lorentz went to work, filming location after location on the ground and from the air in in a lightweight “floppy winged” plane. The crew worked their way up the river from the Gulf of Mexico to Cairo, Illinois, oftentimes working for days on end until principal filming wrapped up in early January 1937. In the end the visuals showed less of the Mississippi and more of the many tributaries that branch off it. This was as much a part of the river’s history as it was the problem, the film purported.

Reaction to a film being made about the Mississippi River was mixed. Although it’s the most important body of drainage water in the U.S., perhaps even the world, and certainly an influential part of the nation’s growth, to many, the river itself, was nothing particularly pleasing to look at. In fact, visually, it’s an eyesore. The water is drab and dirty looking and along it’s shoreline there is very little rock formations or scenery to enhance it. “If driving, you become aware of its presence miles before you reach it,” author Simon Winchester surmises. “The landscape falls away. There are swamps on either side, dense hedgerows and copses, miles of small lakes of curious shape.”

Indeed the Mississippi River, especially its midsection, is banked by mostly mud. Even Mark Twain’s flourishes of the river’s attributes from the perspective of a steamboat pilot couldn’t push the attitudes toward its appearance into anything more than just a very long strip of dirt colored water and sludgy shores.

No question beauty is subjective. Hundreds of quaint cities dot the river’s shoreline and dense tree lines along the Mid to Upper sections provide a multi-colored vista in the Fall. In St Louis, a large man-made monument standing as tall as it is wide (630 feet), greet visitors at the river’s edge; a testament to the men who used the Mississippi’s offshoots to chart the west. When Lorentz made his movie, however, the idea of a symbol like the “Gateway Arch” was nearly 30 years away. But like the early explorers, Lorentz found significance in its vast network too. The tributaries and the people who live along them were the key to its resourcefulness.

The visuals, however, were just part of the overall experience of the 30-minute film. The script, dramatically narrated by an opera singer and actor named Thomas Hardie Chalmers, was not only informational, but poetic too. There’s a good reason why. To promote the project, Lorentz had written two articles for McCall’s magazine. One was wordy and statistical, he thought, so he wrote another version that was more lyrically composed.

From as far East as New York,

Down from the turkey ridges of the Alleghenies

Down from Minnesota, twenty five hundred miles,

The Mississippi River runs to the Gulf.

Carrying every drop of water, that flows down

two-thirds the continent.

Carrying every brook and rill, rivulet and creek,

Carrying all the rivers that run down two-thirds

the continent,

The Mississippi runs to the Gulf of Mexico.

McCall’s chose to publish the latter version and readers responded by writing request letters for copies. Lorentz used the more poetic prose in the film. The music, which incorporated part folk and gospel styles, was written by composer Virgil Thomson.

While the unflinching subject matter certainly raised awareness of the need for more locks and dams, the film is best remembered for it’s cinematic achievements. The film went on to win the “Best Documentary” at the 1938 Venice International Film Festival and the script was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in poetry. The noted novelist and poet James Joyce, shortly before his death at age 60, called the film’s words, “the most beautiful prose that I have heard in ten years.”

Before all the artistic accolades rolled in, upon release in October of 1937, the film titled simply “The River” received positive reviews and general widespread acceptance. The first showing at the White House , however, proved less than ideal. While Roosevelt was generally pleased, the president’s Secretary of Agriculture at the time, Henry Wallace, a Midwesterner from Iowa, didn’t know what to think.

“There’s no corn in it,” he questioned.

The Golden Gate Bridge, Willie Mays, and the Inspiration For ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’

By Ken Zurski

In 1965, while traveling by taxi over the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, television producer Lee Mendelson heard a single version of “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” a Grammy Award winning jazz song written and composed by a local musician named Vince Guaraldi.

Mendelson liked what he heard and contacted the jazz columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Can you put me in touch with Guaraldi? he asked.

Mendelson was a producer at KPIX, the CBS affiliate in San Francisco at the time and had just produced a successful documentary on Giants outfielder Willie Mays. “For some reason it popped into my mind that we had done the world’s greatest baseball player and we should now do a documentary on the world’s worst player, Charlie Brown” Mendelson explained.

“I called Charles Schulz, and he had seen the [Willie Mays] show and liked it.” Mendelson’s mind raced with ideas. That’s when he took a taxi over the idyllic Golden Gate Bridge and was inspired by the music on the radio. Why not score the documentary with jazz music? he thought.

Mendelson called Guaraldi, introduced himself, and asked him if he was interested in scoring a TV special. Guaraldi told him he would give it a go. Several weeks later, Mendelson received a call. It was Guaraldi. I want you to hear something, the composer explained , and performed a version of “Linus and Lucy” over the phone.

Mendelson liked what he heard.

But the documentary never aired. “There was no place for it,” Mendelson said. “We couldn’t sell it to anybody.” Two years later soft drink giant Coca Cola contacted Mendelson and inquired about sponsoring a “Peanuts” Christmas special. “I called Mr. Schulz and I said ‘I think I just sold A Charlie Brown Christmas,’ and he said ‘What’s that?’ and I said, ‘Something you’re gonna write tomorrow.”

Mendelson decided to use Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy,” which had already been composed for the documentary. “The show just evolved from those original notes,” Mendelson described.

The rest is musical animation perfection.

Over the next 10 years, Guaraldi would score numerous “Peanuts” television specials, plus the feature film “A Boy Named Charlie Brown.” Then in 1976, it sadly ended. In a break during a live performance at Menlo Park , California, Guaraldi died from an apparent heart attack. He was 47

Although Guaraldi was working on another “Peanuts” special at the time of his death, his first score, “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” is still his most famous and most popular work.

The soundtrack released shortly after the special in 1965 and reissued in several formats since, remains one of the top selling Christmas albums of all-time.

(Sources: Animation Magazine – Lee Mendelson, Producer of This is America, Charlie Brown and all of the other Peanuts primetime specials – Sarah Gurman June 1st, 2006; various internet sites).

When Generalship Had Its Limits

By Ken Zurski

In the new book The General vs the President, author H.W. Brands examines the often tenuous but respectful relationship between General Douglas MacArthur and President Harry Truman. Besides their differing personalities, in the public eye, the two men drew widely opposite impressions. Truman had unexpectedly assumed the presidency amidst doubts about his leadership and foreign policy experience while MacArthur was the beloved general of the Allied forces in the Pacific.

Preconceived notions, however, good or bad, don’t win wars. After World War II ended and when North Korea threatened South Korea, both men had vastly different views on how America should proceed. Truman gave MacArthur leverage, but when China was drawn into the conflict and the two world powers were nearly brought to the brink of a nuclear war, Truman relieved the popular general of his duties. “With deep regret I have concluded that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur is unable to give his wholehearted support to the policies of the United States Government and of the United Nations in matters pertaining to his official duties,” Truman announced at a press conference. That explosive missive is the basis of Brand’s book.

But Truman, as important as he was to ending the war, was just a senator from Missouri when President Franklin Roosevelt crossed ways with MacArthur. That relationship nearly reached the boiling point in 1941, shortly after Japan attacked Pear Harbor.

It’s worth a closer look.

MacArthur who is in the Philippines at the time Pearl Harbor was attacked feared the American bases on the island would be next. He was right. The next day, December 8, Japan hit hard. MacArthur asked Roosevelt to immediately strike back. Force Russia to attack Japan, he pressed, before Japan can do more damage in the Philippines. Roosevelt ignored MacArthur’s plea and set his sights on Germany instead.

MacArthur’s rebuttal was shocking. He supported a plan by Philippine President Manuel Quezon to broker a peace deal with Japan. It was the only way, MacArthur agreed, to avoid a “disastrous debacle.”

In retrospect, Brands assumes, MacArthur was abandoning the Philippines. But there were lives at stake. A defiant Roosevelt dismissed the peace deal. “American forces will continue to fly our flag in the Philippines,” the president commanded, “so long as there remains any possibility of resistance.”

Back home, MacArthur was being criticized for poor decision making. Brands points out the there was a nine-hour window after the first dispatches were received that Japanese bombers were in the air. There was nothing anyone could do about the battleships in the Harbor; but in the Philippines, why didn’t MacArthur order the planes moved out of the way? MacArthur subsequently blamed his subordinates and miscommunication. Nevertheless, half of the MacArthur’s forces were decimated in the attack and the Philippine’s line of defense was greatly diminished.

It would get worse. The conquest of the Philippines by Japan is still considered one of the worst military defeats in U.S. history.

MacArthur endured attacks from Japan forces by hunkering down on the Bataan peninsula and Corregidor Island. “Help is on the way,” MacArthur told the men, although he knew it was a lie. “Thousands of troops and hundreds of planes are being dispatched ,” he continued, hoping to boost morale. None of it was even being considered.

The only order coming from Roosevelt was getting his four-star general out of the islands before all hell broke loose. MacArthur had no recourse. It was an order, not a choice. He took the next plane out and flew to Australia where he was to organize the counter offense against Japan and pave the way to his own interminable place in American history. Roosevelt would later praise his departure, but MacArthur felt like he was abandoning his post.

Before boarding he told the troops, “I shall return.”

When MacArthur did return three years later he was hailed as a hero. “Though not by American soldiers he left behind [in the Philippines],” Brands writes in the book.