Uncategorized

Exploring Dr. Seuss’s Whimsical Songwriting

By Ken Zurski

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, wrote dozens of children’s books that still today reach bestseller’s lists and thrill a new generation of fans each and every year. However, his work as a songwriter is often overlooked, due in part to the success of his books. But when reminded, the songs penned by Seuss, are just as enduring and whimsical.

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, wrote dozens of children’s books that still today reach bestseller’s lists and thrill a new generation of fans each and every year. However, his work as a songwriter is often overlooked, due in part to the success of his books. But when reminded, the songs penned by Seuss, are just as enduring and whimsical.

Seuss wrote the songs mostly for television animated specials. And if you know the shows, you know the songs. For instance, in The Cat in the Hat, a television short released in 1970, and based on his first children’s book of the same name, Geisel wrote several original songs including the bouncy, “The Gradunza” (The old, moss-covered, three-handled family gradunza), the catchy “Cat, Hat” (Cat, hat, in French, chat, chapeau. In Spanish, el gato in a sombrero.),” and the playfully teasing, “Calculatus Eliminatus” (Calculatus eliminatus always helps an awful lot. The way to find a missing something is to find out where it’s not), all with Seuss’s clever wordplay and sing-song rhyme pattern .

One song in particular, “I’m a Punk,” introduced such ridiculously pleasing locutions as crontunculous, gropulous, poobler, and schnunk. ” While everyone understands the meaning of punk, being a “schnunk” needed some explanation. But when the Cat sings, “nobody, likes me, not one tiny hunk,” everyone gets the idea.

One song in particular, “I’m a Punk,” introduced such ridiculously pleasing locutions as crontunculous, gropulous, poobler, and schnunk. ” While everyone understands the meaning of punk, being a “schnunk” needed some explanation. But when the Cat sings, “nobody, likes me, not one tiny hunk,” everyone gets the idea.

Some credit the Seuss writing style to a Life magazine article in 1956 that criticized children’s reading levels, specifically “primers” or textbooks with simplified words and phrases like “See Spot run” from the book series Fun with Dick and Jane. Geisel was asked to write a story using a vocabulary list of just over 200 words. He picked the first two words that rhymed, cat and hat, and went from there. It certainly wasn’t like any story in a textbook, that’s for sure, and critics praised “The Cat in the Hat” for its originality.

Several years later when Seuss wrote the lyrics for songs in his television specials, he seemed to relish the opportunity to ratchet up the silliness even more. Seuss’s words just seemed to work with music, oftentimes using traditional melodies, sometimes with an original score. The man credited with composing or arranging most of the music for Seuss is Dean Elliott, a Midwesterner from Wisconsin, who conducted orchestras for the Tom and Jerry shorts before hooking up with Seuss. Later Elliott worked with Bugs Bunny creator Chuck Jones.

Seuss’s most popular song is one we hear every year around the holidays. In it, an unmissable deep voice groans about the Grinch, a Seuss original, who has a “heart full of unwashed socks” and a “soul full of gunk.”

Seuss’s most popular song is one we hear every year around the holidays. In it, an unmissable deep voice groans about the Grinch, a Seuss original, who has a “heart full of unwashed socks” and a “soul full of gunk.”

Written in 1966 for the TV special “How the Grinch Stole Christmas,” Seuss enlisted a voice actor named Thurl Ravenscroft to sing the lead on the song even though Boris Karloff was the voice of the Grinch in the special. Karloff reportedly could not sing and Ravenscroft was hired . But Ravencroft’s name was never listed among the credits and Karloff mistakenly got most of the acclaim. Seuss was reportedly furious and apologized for the oversight. Ravenscroft was also the voice of Kellogg’s Tony the Tiger (They’re Great!).

“You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch,” is an unconventional Christmastime staple. The song never mentions Christmas, but rather teases with crafty metaphors, comparisons and contradictions all designed to point out what an awful crank the Grinch – now a symbol of holiday grumpiness – can be.

You’re a mean one Mr. Grinch

You really are a heel.

You’re as cuddly as a cactus,

And as charming as an eel,

Mr. Grinch!

The song is instantly recognizable, charming and unmistakably Dr. Seuss.

The songwriter.

“The Greatest Gift” is a Christmas Story You Know Well

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

In November 1939 Philip Van Doren Stern, an American author, editor and Civil War historian wrote an original story titled “The Greatest Gift,” a heartwarming Christmas tale about a man named George Pratt who gets a dying wish granted by a guardian angel that literally changes his life.

The story begins at an iron bridge as a despondent George leans over the rail:

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” a quiet voice beside him

said.George turned resentfully to a little man he had never seen

before. He was stout, well past middle age, and his round

cheeks were pink in the winter air as though they had just been

shaved. “Wouldn’t do what?” George asked sullenly.

“What you were thinking of doing.”

“How do you know what I was thinking?”

“Oh, we make it our business to know a lot of things,” the

stranger said easily.

Stern desperately tried to get his little story published, but it never sold. So in 1943, he made it into a Christmas card book and mailed 200 copies to family and friends.

The story caught the attention of RKO Pictures producer David Hempstead, who showed it to Cary Grant’s agent. In April 1944, RKO bought the rights but failed to create a satisfactory script. Grant went on to make “The Bishop’s Wife.”

Hollywood director Frank Capra, however, liked the idea and RKO was happy to unload the rights. Capra bought it and brought in a slew of writers to polish the story.

The screenplay and resulting film was renamed “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

“The Most Magical Two Minutes” Almost Never Aired

By Ken Zurski

When “A Charlie Brown Christmas” was produced for television in 1965, Peanuts creator Charles Schulz had one specific, but important directive. That the program be about something. Namely, he insisted, it be about the true spirit of Christmas. Otherwise, he said, “Why bother?

Of course, as we know now, Schulz had his way. Mostly lighthearted and inspirational, “A Charlie Brown Christmas” is punctuated by its infectious original music, a catchy tunes, and the now iconic symbol of recognition and hopefulness: a seemingly lifeless little tree.

The highlight of the special , however, is a moving scene in which the Linus character, blanket in hand, stands on a spotlighted stage and explains the true meaning of Christmas. It includes a biblical passage from the Book of Luke.

As Linus recites:

And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid. And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord. And this [shall be] a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

Then like magic, Linus addresses someone specifically: “That’s what Christmas is all about, Charlie Brown.”

Linus’s words, like the special itself, has been charming audiences ever since.

Charming, however, was not the word CBS executives used when they first viewed the completed special. They hated it -– or just didn’t get it. The pacing was off, they thought, and the music was different: classical in parts, jazzy in others.

Charming, however, was not the word CBS executives used when they first viewed the completed special. They hated it -– or just didn’t get it. The pacing was off, they thought, and the music was different: classical in parts, jazzy in others.

They considered scraping it altogether, but were committed to the time slot and soft drink giant Coca-Cola, the sponsor of the program. “This is probably going to be the last [Peanuts special],” one executive chirped. “But we got it scheduled for next week, so we’ve got to air it.”

The producers of the special were deflated by the network’s initial reaction. “We thought we’d ruined Charlie Brown,”one exclaimed. Until then, the only controversy among the writers was whether or not to include the use of an actual biblical verse in an animated special. Schulz again insisted. “If we don’t do it,” he said “who will.” Coca-Cola gave their blessing too.

Linus’s effective speech is also credited to the child actor who provided the voice. Before the special, Peanuts characters had only been heard in a Ford Commercial. The producers wanted them all to be voiced by children. Christopher Shea was only 8 years old at the time. He had the most innocent sounded voice and was tapped for the Linus character. His measured, straightforward reading is considered legendary. “It’s one of the most amazing moments ever in animation,” raved Peter Robbins, the original voice for Charlie Brown. Robbin’s voice was picked for Charlie Brown because it sounded “blah.”

Even though CBS thought it would only run for a year and be forgotten, once it was in the public consciousness, attitudes changed. Instantly, people began talking about it. The next year, the special won a Peabody award and an Emmy for Outstanding Christmas Programming. A lasting tribute to Charles Schulz original vision that it be about something – – something with a message.

One scene in particular is still considered, as a producer described it later, as “the most magical two minutes in all of TV animation.”

The Real History Behind Black Friday: the Day and that Song

By Ken Zurski

Before Americans began rushing to stores the day after Thanksgiving and calling the shopping frenzy “Black Friday,” the term itself was used to describe a dark and devious part of our nation’s history.

One that was mostly forgotten until 1975 when a group named Steely Dan immortalized it in song. But still to this day. most people don’t know what the song is really about:

“When Black Friday comes

I stand down by the door

And catch the grey men when they

Dive from the fourteenth floor”

Here’s the story:

The original “Black Friday” begins with a man named Jay Gould.

A leather maker turned New York railroad owner, Gould was the youngest of six children, the only boy, and a scrawny one at that; growing up to be barely five feet tall. What he lacked in size, however, he made up for in ambition.

A financial whiz even as a young man, Gould started surveying and plotting maps for land in rural New York, where he grew up. It was tough work, but not much pay, at least not enough for Gould. In 1856 he met a successful tanner – good work at the time – who taught Gould how to make leather from animal skins and tree bark. Gould found making money just as easy as fashioning belts and bridles. He found a few rich backers, hired a few men and started his own tanning company by literally building a town from scratch in the middle of a vacant but abundant woodland. When the money started to flow, the backers balked, accusing Gould of deception. Their suspicions led to a takeover. The workers, who all lived quite comfortably in the new town they built and named Gouldsborough, rallied around Gould and took the plant back by force, in a shootout no less, although no one was seriously hurt.

Gould won the day, but the business was ruined. By sheer luck, another promising venture opened up. A friend and fellow leather partner had some stock in a small upstate New York railroad line. The line was dying and the stock price plummeted. So Gould bought up the stock, all of it in fact, with what little earnings he had left, and began improving the line. Eventually the rusty trail hooked up with a larger line and Gould was back in business. He now owned the quite lucrative Erie Railroad.

Ten years later, in 1869, Gould turned his attentions to gold.

When Black Friday comes

I collect everything I’m owed

And before my friends find out

I’ll be on the road

Gold was being used exclusively by European markets to pay American farmers for exports since the U.S currency, greenbacks, were not legal tender overseas. Since it would take weeks, sometime months for a transaction to occur, the price would fluctuate with the unstable gold/greenback exchange rate. If gold went down or the greenback price went up, merchants would be liable -often at a substantial loss – to cover the cost of the fluctuations. To protect merchants against risk, the New York Stock Exchange was created so gold could be borrowed at current rates and merchants could pay suppliers immediately and make the gold payment when it came due. Since it was gold for gold – exchange rates were irrelevant.

Gould watched the markets closely always looking for a way to trade up. He reasoned that if traders, like himself, bought gold then lent it using cash as collateral, large collections could be acquired without using much cash at all. And if gold bought more greenback, then products shipped overseas would look cheaper and buyers would spend more. He had a plan but needed a partner.

He found that person in “Gentleman Jim Fisk.”

Jim Fisk was a larger than life figure in New York both physically and socially. A farm boy from New England, Fisk worked as a laborer in a circus troupe before becoming a two-bit peddler selling worthless trinkets and tools door to door to struggling farmers. The townsfolk were duped into calling him “Santa Claus” not only for his physical traits but his apparent generosity as well. When the Civil War came, Fisk made a fortune smuggling cotton from southern plantations to northern mills.

So by the time he reached New York, Fisk was a wealthy man. He also spent money as fast as he could make it; openly cavorted with pretty young girls; and lavished those he admired with expensive gifts and nights on the town. Fisk never hid behind his actions even if they were corrupt. He would chortle at his own genius and openly embarrass those he was cheating. He earned the dubious nickname “Gentleman” for being polite and loyal to his friends.

Fisk and Gould were already in the business of slippery finance. Besides manipulating railroad stock (Fisk was on the board of the Erie Railroad), they dabbled in livestock and bought up cattle futures when prices dropped to a penny a head. Convinced they could outsmart, out con and outlast anyone, it was time to go after a bigger prize: gold. There was only $20 million in gold available in New York City and nationally $100 million in reserves. The market was ripe for the taking and both men beamed at the prospects.

When Black Friday falls you know it’s got to be

Don’t let it fall on me

But the government stood in the way. President Grant was trying to figure out a way to unravel the gold mess, increase shipments overseas and pay off war debts. If gold prices suddenly skyrocketed, as Gould and Fisk had intended, Grant might consider a proposed plan for the government to sell its gold reserves and stabilize the markets; a plan that would leave the two clever traders in a quandary.

Through acquaintances, including Grant’s own brother-in-law, Gould and Fisk met with the president. In June of 1869, they pitched their idea posing as two concerned (a lie) but wealthy (true) citizens who could save the gold markets and raise exports, thus doing the country a favor. They insisted the president let the markets stand and keep the government at bay. Fisk even treated the president to an evening at the opera – in Gould’s private box. The wily general may have been impressed by the opera, but he was also a practical man. He told the two estimable gentlemen that he had no plans to intervene, at least not initially. But Grant really had no idea what the two shysters were up to.

A few months later, when Fisk sent a letter to Grant to confirm the president’s steadfast support, a message arrived back that Grant had received the letter and there would be no reply. The lack of a response was as good as a “yes” for Fisk. Grant was clearly on board, he thought.

He was wrong.

“When Black Friday comes

I’m gonna dig myself a hole

Gonna lay down in it ’til

I satisfy my soul”

On September 20th, a Monday, Fisk’s broker started to buy and the markets subsequently panicked. Gold held steady at first at $130 for every $100 in greenback, but the next day Fisk worked his magic. He showed up in person and went on the offensive. Using threats and lies, including where he thought the president stood on the matter, Fisk spooked the floor.

The Bulls slaughtered the Bears.

Gold was bought, borrowed and sold. And Fisk and Gould, through various brokers, did all the buying. On Wednesday, gold closed slightly over 141, the highest price ever. In his typical showy style, Fisk couldn’t help but rub it in. He brazenly offered bets of 50-thousand dollars that the number would reach 145 by the end of the week. If someone took that sucker proposition, they lost. By Thursday, gold prices hit an astounding 150. The next day it would reach 160.

Then the bottom fell out.

At the White House, Grant was tipped off and furious. On September 24, a Friday, he put the government gold reserve up for sale and Gould and Fisk were effectively out of business. Thanks to the government sell off, almost immediately, gold prices plummeted back to the 130’s. Many investors lost a bundle, but the two schemers got out mostly unscathed.

The whole affair became famously known as “Black Friday.”

When Black Friday comes

I’m gonna stake my claim

I guess I’ll change my name

In 1975, Steely Dan, the rock group consisting of multi-instrumentalist Walter Becker and singer Donald Fagen, wrote a song about it. “Black Friday” was released that same year on their “Katy Lied” album. It was the first single off the album and reached #37 on the Billboard charts.

The song is about the 1869 Gould/Fisk takeover but confuses some listeners due to it’s reference to an Australian town named Muswellbrooke (“Fly down to Muswellbrook”) and the line about kangaroos (“Nothing to do but feed all the kangaroos”).

Fagen later confirmed in an interview the town name was added by chance: “I think we had a map and put our finger down at the place that we thought would be the furthest away from New York or wherever we were at the time. That was it.”

Today the term “Black Friday” is referenced in relation to the Friday after Thanksgiving, traditionally the busiest shopping season of the year and the day retailers go “in the black,” so to speak.

Steely Dan had none of that in mind when they wrote the song.

(“Black Friday” written by Donald Jay Fagen, Walter Carl Becker • Copyright © Universal Music Publishing Group)

When the President Ordered Thanksgiving One Week Earlier

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

In September of 1939, Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a presidential proclamation to move Thanksgiving one week earlier, to November 23, the fourth Thursday of the month, rather than the traditional last Thursday of the month, where it had been observed since the Civil War.

Roosevelt was being pressured to make the change by the National Retail Dry Goods Association. The NRDGA was reeling from the Great Depression and sensed a disaster in holiday sales since Thursday of that year fell on the 30th, the fifth week and final day of November, and late for the start of the Christmas shopping season.

The business owners went to Commerce Secretary Harry Hopkins who went to the President. Help out the retailers, Hopkins pleaded. Roosevelt listened. He was trying to save the economy not break it. Thanksgiving would be celebrated one week earlier, he announced.

Apparently, the move was within his presidential powers to suggest since no precedent was set. Thanksgiving, the day, was not federally mandated and the actual date had been moved before. Many states, however, balked at Roosevelt’s plan. Schools had a scheduled day off for the last Thursday of the month and a host of other events like football games, both at the local and college level, would have to be cancelled or moved. One irate coach threatened to vote “Republican” if Roosevelt interfered with his team’s schedule.

Others at the government level were similarly upset. “Merchants or no merchants, I see no reason for changing it,” chirped an official from the opposing state of Massachusetts. In jest, Atlantic City Mayor Thomas Taggart, a Republican, dubbed the early date, “Franksgiving.”

However, Illinois Governor Henry Horner echoed the sentiments of those who may not have agreed with the switch, but dutifully followed orders. “I shall issue a formal proclamation fixing the date of Thanksgiving hoping there will be uniformity in the observance of that important day,” he declared. Horner was a Democrat and across the country opinions about the change were similarly split down party lines: 22 states were for it; 23 against and 3 went with both dates.

It didn’t matter to Roosevelt at first. He made the change official for the succeeding two years, since Thursday would fall late in the calendar both times. But in 1941, The Wall Street Journal released data that showed there was little to no significant change in retail sales.

Roosevelt admitted he was wrong, but in hindsight, on the right track. Thanks to the uproar, later that year, Congress approved a joint resolution making Thanksgiving a federal holiday to be held on the fourth Thursday of the month, regardless of how many weeks were in November.

Roosevelt signed it into law.

The Invasion of the “Body Snatchers”

By Ken Zurski

In the new book Hero of the Empire, author Candice Millard explores the military career of a young Winston Churchill and the future Prime Minister of England’s exploits in the Boers War, a devastating conflict against the fiercely independent South African Republic of Transvall, or Boers, that’s as much a part of British history as the two subsequent World Wars.

In the new book Hero of the Empire, author Candice Millard explores the military career of a young Winston Churchill and the future Prime Minister of England’s exploits in the Boers War, a devastating conflict against the fiercely independent South African Republic of Transvall, or Boers, that’s as much a part of British history as the two subsequent World Wars.

In 1899, Churchill was in his twenties and officially not a soldier, per se, but a correspondent for the Morning Post. However, he bravely and willingly fought alongside his fellow countrymen. When a British armored train was ambushed, Churchill fought back, was captured, imprisoned, managed to escape, and traversed hundreds of miles of enemy territory to freedom. He then returned and resumed his duties in the war. Millard’s expert narrative paints the young Churchill as a man of great strength, determination and steadfast loyalty.

The same attributes can also be applied to another famous figure in history who did not fight like Churchill, but bravely dodged the bullets of the Boers to do a thankless and daring task. His contribution is touched on briefly in the book, but is worth noting here as an example of a man whose legacy of peace and non-violence includes the brutal reality of warfare.

In stark contrast to Churchill’s call to arms, this figure refused to pick up a weapon or engage in hand to hand combat. His Hindu faith prevented that, but his desire for justice could not be suppressed. He was an Indian-born lawyer in a country under the flag of the British Empire who went to South Africa to defend his people from cruelty imposed by the Boers. When war broke out, he wanted to contribute, along with other persecuted Hindu followers. But how?

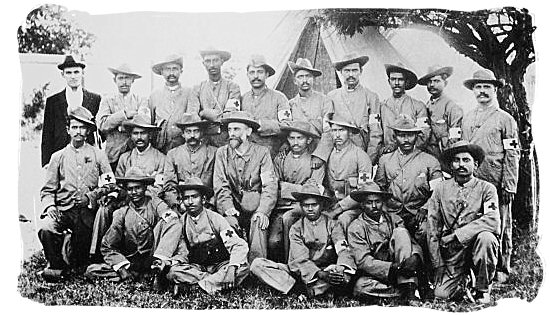

So he asked the British government if he could put together a team of men to perform the incessant task of removing bodies, dead or wounded, from the heat of battle. The government approved the request, but made it clear that the men were under no obligation or safeguards from the British Army. The decision to risk their own lives in order to save others was theirs and theirs alone.

“Body snatchers,” was the term used by British troops to describe the men who retrieved “not just bodies from the battlefield, they hoped, but young men from the jaws of death,” Millard writes. The “body snatchers” wore wide brim hats and simple loose fitting khaki uniforms and were distinguished by “a white band with a red cross on it wrapped around their left arms.”

Their efforts were lauded by superiors and observers alike. “Anywhere among the shell fire, you could see them kneeling and performing little quick operations that required deftness and steadiness of hand,” wrote John Black Atkins a reporter for the Manchester Guardian.

By now you may discern that the person who assembled this unusual band of brave men is important to history. Millard doesn’t hold anyone in suspense. She doesn’t need to. The man was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the thirty-one year-old leader of the “body snatchers.”

“Although his convictions would not allow him to fight,” Millard writes, “he had gathered together more than a thousand men to form a corps of stretcher bearers.”

Later in his autobiography, Gandhi would recall his role in the Boers War.

“We had no hesitation,” he wrote.

The Unlikely and Unliked 13th President of the United States

By Ken Zurski

On July 10, 1850, Millard Fillmore became the 13th President of the United States.

It didn’t go so well.

The unsuspecting Fillmore, a lawyer and former congressman from New York, had been vice president to Zachery Taylor at the time, a job he sought but ultimately didn’t think he would get. Even Taylor, a popular military general, had reservations about running for the office of president. But duty called. “If my friends deem it good for the country that I be a candidate,” Taylor obliged. “so be it.”

Fillmore, who was not known as politically savvy or ambitious, tagged along.

Once in the White House, however, Fillmore had little to do. The job held no great power or influence and only one vice president, John Tyler, had ever assumed the presidency unexpectedly. That changed when only sixteen months after being elected, Taylor was dead. A bad stomachache and poor medical care did him in. A stunned Fillmore took the oath of office and set the stage for what is considered one of the worst presidencies in history.

Here’s why it began so poorly…

Almost immediately after Taylor’s death, the members of his cabinet, in ceremonial unity and respect to the late president, turned in resignation letters. They fully expected Fillmore to deny their requests. Fillmore was unproven and needed their help. Plus, Fillmore and Taylor were teammates, not adversaries. Whether they personally liked the vice president or not, and most did not, a nation’s stability and Taylor’s legacy was at stake.

Clearly, they thought, Fillmore could grasp that.

They were wrong.

Fillmore was either intimidated by the experience of others, stubborn, or didn’t care. He accepted their resignation letters and basically told them all to leave. Then in an unexpected and clearly brazen move, he asked them all to stay on another month. So he could appoint a new team, Fillmore told them.

Each one refused.

How the Dilemma of the Fourth Dimension and a Progressive Teacher Taught Children How To Play

By Ken Zurski

Mathematician Charles Howard Hinton was both equally fascinated and frustrated by the concept of the fourth dimension, also known as the “other dimension,” or the one dimension of time and space that no one had been able to verify or explain. Albert Einstein tried. He deduced in his Theory of Special Relativity that the fourth dimension is “time” and that “time is inseparable from space.” Since then science fiction writers have used the space-time continuum to great dramatic effect in their stories.

But in 1884, while Einstein was still a toddler, it was Hinton who wrote the definitive article on the subject. In “What is the Fourth Dimension?” Hinton explained that the theory behind a fourth dimension was firmly established, but there was no physical evidence to support it. That was the dilemma, he inferred: “If we think of a man as existing in four dimensions, it is hard to prevent ourselves from conceiving him prolonged in an already known dimension.” Hinton used a four-cornered room, or cube, for example, to explain how one can only reach three dimensions. “Space as we know it, is subject to limitation,” he conceded.

However, to teach his children math skills, Hinton built a three-dimensional bamboo dome with evenly spaced geometric shapes. His son, Sebastian, remembers climbing and hanging from the dome while his father called out intersections for the children to identify.

“X2, Y4, Z3, Go!” Hinton would command.

Hinton died unexpectedly in 1907 from a cerebral hemorrhage. While he is mostly remembered for his work on the fourth dimension, in stark contrast, he is also credited with introducing the first pitching machine (for baseball) – more like a gun – called the “mechanical pitcher,” and designed for the Princeton University team. The machine used gunpowder to fire the ball.

But the geometric dome he created for his children also had a lasting effect. Especially on his youngest son Sebastian.

Here’s why:

Sebastian ended up marrying a teacher, Carmelita Chase, who grew up in Omaha, Nebraska and moved to Chicago in 1912 to become Jane Adams’ secretary at Hull House. That’s when she met Sebastian, a patent lawyer in town.

Carmelita was pretty, smart, and multi-talented. In college, she excelled in tennis (among other sports), acted in plays and sang in the choir. “She has distinguished herself in athletics as well her studies,” the Chicago Daily Tribune described in announcing the couple’s engagement in 1916. She and Sebastian would eventually have three children.

Shortly after getting married, however, Carmelita put most of her time and efforts into her work. She opened a kindergarten and nursery school at her Chicago apartment which was directly across from a park.

“Frustrated by her own ‘dreary’ school experience, she was determined to create learning environments for her school children and others that would be joyfully experimental,” author Susan Ware wrote about Carmelita in Notable American Women.

The type of teaching she endorsed already had a name: progressive education. For Carmelita, this included incorporating more outdoor activities like hiking, camping, farming and the care of animals to daily activities. “She would come into a room and it would be an explosion,” a former student recalled in the book Founding Mothers and Others, “But it was a happy occasion. She could sweep people up and carry them to Mars.”

In 1920, while watching his wife’s school children playing outside their Winnetka, Illinois home, Sebastian had a revelation. Why not build something they could climb on?

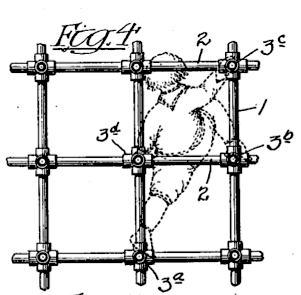

He envisioned a three-dimensional structure similar to his father’s geometric dome, but for play rather than instruction. He reportedly jotted down the idea on a napkin and perfected the plan for a patent submission. Then he built it.

Hinton called it a Jungle Gym.

At the time of its conception, however, the Jungle Gym was never heralded as the important contribution to the children’s playground as it is today. In fact, Hinton’s only recorded words about his invention are attributed to his detailed patent filings: “Children seem to like to climb through the structure and swing their head downward by the knees, calling back and forth to each other. A trick which can only be explained of course by a monkey’s instinct.” While the name Jungle Gym never officially changed, many people began seeing the correlation with the primate’s distinctive behavior and started calling it “monkey bars” instead. The moniker stuck.

Unfortunately, Sebastian Hinton is a figure lost to time. Although he married a socialite in Carmelita, Hinton preferred to stay out of the spotlight. Tragically, just a few years after creating the Jungle Gym, he committed suicide in a clinic after reportedly being treated for depression.

Caremilta chose not to publicly disclose her husband’s illness and cause of death (he hung himself). She packed up the family and moved east. Today, she is best remembered for founding Putney School, an independent progress education institution in Vermont that is still in existence today.

Hinton’s original Jungle Gym is permanently on display in the backyard of the Winnetka Historical Society Museum.

As Many as 15 Supreme Court Justices? That Was the Plan

By Ken Zurski

On February 5, 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced his intention to expand the Supreme Court to as many as 15 justices. The plan was clearly political. Roosevelt was trying to “pack” the court, Republicans argued, and in turn make the nation’s highest court a completely liberal entity.

On February 5, 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced his intention to expand the Supreme Court to as many as 15 justices. The plan was clearly political. Roosevelt was trying to “pack” the court, Republicans argued, and in turn make the nation’s highest court a completely liberal entity.

Roosevelt embraced the criticism and mostly ignored it. Although politically it was still a hot button issue, his New Deal policies had earned public acceptance, even praise. As president, he reached for the stars.

Here’s why it mattered to Roosevelt. The high court had previously struck down several key pieces of his New Deal legislation on the grounds that the laws delegated an unconstitutional amount of authority in government, specifically the executive branch, but especially the office of the president.

Roosevelt won the 1936 election in a landslide and was feeling a bit emboldened. If he could pack the court, he could win a majority every time. The president proposed legislation which in essence asked current Supreme Court justices to retire at age 70 with full pay or be appointed an “assistant” with full voting rights, effectively adding a new justice each time.

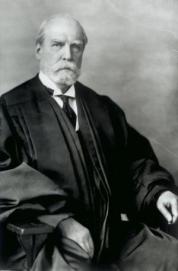

This initiative would directly affect the 75-year-old Chief Justice, Charles Evan Hughes, a Republican from New York and a former nominee for president in 1916 who narrowly lost to incumbent Woodrow Wilson. Hughes resigned his post as a Supreme Court Justice to run for president, then served as Secretary of State under the Harding administration. In 1930, he was nominated by Herbert Hoover to return to the high court as Chief Justice. Hughes had sworn in Roosevelt twice. Now he was being asked by the president to give up his post.

In May of 1937, however, Roosevelt realized his “court packing” idea was wholly unnecessary. Two justices, including Hughes, jumped over to the liberal side of the argument and by a narrow majority upheld as constitutional the National Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act, two of the administration’s coveted policies. Roosevelt never brought up the issue of the court size again.

But his power move didn’t sit well with the press.

Newspaper editorials criticized him for it and the public’s favor he had enjoyed after two big electoral victories was waning. He was a lame duck president finishing out his second term. Then Germany invaded Poland. Roosevelt’s steady leadership was lauded in a world at war. In 1940, he ran for an unprecedented third term and won easily.

The following year, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Truth Be Told: The Landmark Libel Case That Nearly Stopped the Press

By Ken Zurski

On November 17, 1734, a German immigrant and printer named John Peter Zenger, known for his influential newspaper, the New York Weekly Journal, was thrown in jail for seditious libel.

Zenger was accused of printing unflattering and damaging stories about William S. Cosby, the 24th colonel governor of the Province of New York. Among other things, the Journal claimed Cosby rigged elections, stole collected taxes, misappropriated Indian lands, and allowed enemy ships, like the French, to dock in New York harbor. This was tantamount to treason, the article implied.

The article provoked an already dubious reputation. As a public servant, Cosby was known as a notoriously giving man, but only for the benefit of his fellow Royalists. He tried and often failed to secure higher salaries for his friends and officers. The Journal finally unleashed an onslaught of charges against him.

Cosby fired back, ordering his men to burn up the remaining editions of the Journal, claiming libel laws, and demanding justice. In the early 18th century, under British rule, any information published that was opposed to the monarchy was considered a violation of the law. The truth, as it was understood, was irrelevant. Cosby had a case.

But who to blame?

Zenger was the printer of the article and claimed not to have written it. But when asked to reveal the name of the writer – or writers – listed as anonymous in the paper, he refused. Zenger was arrested, incarcerated and left to await trail. Nearly a year later, in August of 1735, when the jury was finally seated, the Chief Justice in the case, James DeLancey, thought the proceedings would end quickly.

He was right, to a point.

A lawyer from Philadelphia named Andrew Hamilton was called upon to serve as Zenger’s counsel . The Scotland born Hamilton practiced law in Maryland and Pennsylvania and oftentimes traveled between the two provinces to accept cases and appointments. He mostly avoided New York. But when Zenger’s lawyers, a couple of locals, were stricken from the case because they had objected to DeLancey’s commission, Hamilton, a friend and an outsider, stepped in.

Hamilton went to work. He demanded the prosecution prove the allegations were false or the jury must free Zenger immediately. “It is not the cause of one poor printer,” Hamilton insisted, “but the cause of liberty.”

Hamilton’s words were prophetic and Zenger’s case would begin a contentious debate that would last until 1791 when under a new constitution of laws, the expression known as “Freedom of Press,” was included in the very first amendment of the Bill of Rights.

But that precedent would be set only if Hamilton was persuasive enough to exonerate Zenger. Libel only exists when falsehoods are perpetrated, not the truth, he argued.

It took the jury less than ten minutes to come back with a verdict.

“Not guilty” was their response.