It’s Time to Salute the Golden Eagle, Not Just the Bald One

By Ken Zurski

It’s hard to imagine anything other than the majestic bald eagle as the symbol of the United States of America, but back in the late 18th century, when good and honorable men were deciding such things, there were several considerations vying for a symbol which best represented the new country.

Benjamin Franklin was one such decider. Although Franklin didn’t quite nominate another bird, the turkey, as some history lessons would suggest, it was the use of the bald eagle as the symbol of America that most infuriated the elder statesman.

“[The bald eagle] is a bird of bad moral character,” Franklin wrote to his daughter. “He does not get his Living honestly.”

For Franklin it was a a matter of principal. The bald eagle was a notorious thief, he implied. Here’s why the perception is a reasonable one at least: Bald eagles are considered good gliders and even better observers. Therefore, they often watch other birds, like the more agile Osprey (appropriately called a fish hawk) dive into water to seize its prey. The bald eagle then assaults the Osprey and forces it to release the catch, grabs the prey in mid-air, and returns to its nest with the stolen goods. “With all this injustice,” Franklin wrote as only he could, “[The bald eagle] is a rank coward.”

Franklin then expounded on the turkey comparison: “For the truth, the turkey is a much more respectable bird…a true original Native of America who would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his farmyard with a red coat on.”

Regardless of his turkey argument, was Franklin’s assessment of the bald eagle as a “coward” a fair one?

Ornithologists today provide a more scientific and sensible explanation. In the”Book of North American Birds” the bald eagle gets its just due, for as a bird, it’s actions are justifiable. “Nature has her own yardstick, and in nature’s eyes the bald eagle is blameless. What we perceive as laziness is actually competence.” Being able to catch a “waterfowl in flight and rabbits on the run,” the book suggests is a noble and rewarded skill.

Perhaps, a better choice for the nation’s top bird, might have been the golden eagle, who unlike the bald eagle captures its own prey, mostly small rodents, but is powerful enough to attack larger animals like deer or antelope on rare occasions. (Its reputation today is tainted somewhat by rumors that it snatches unsuspecting domestic animals, like goats or small dogs.) But golden eagles don’t want attention. They shy away from more populated areas and appear to be “lazy” only because they can hunt with such precision and ease they don’t really have to ruffle their feathers.

The reason why America chose the bald eagle over the golden eagle to be the nations symbol, however, seems obvious by default. History had already pinned the golden eagle as a symbol of warrior strength and victory (“perched on banners of leading armies, the fists of emperors and figuring in religious cultures)” among other heroic and stately attributes. Basically, the golden eagle had been taken.

The bald eagle, by comparison, would be truly American.

Perhaps when Franklin made the disparaging comments against the bald eagle he was also harboring a nearly decade old grudge.

In 1775, a year before America’s independence, Franklin wrote the Pennsylvania Journal and suggested an animal be used as a symbol of a new country, one that had the “temper and conduct of America,” he explained. He had something in mind. “She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders;” he wrote. “She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage”

Franklin’s choice: the rattlesnake.

Teddy’s ‘Immensely Pleasing’ Feisty Blue Macaw

By Ken Zurski

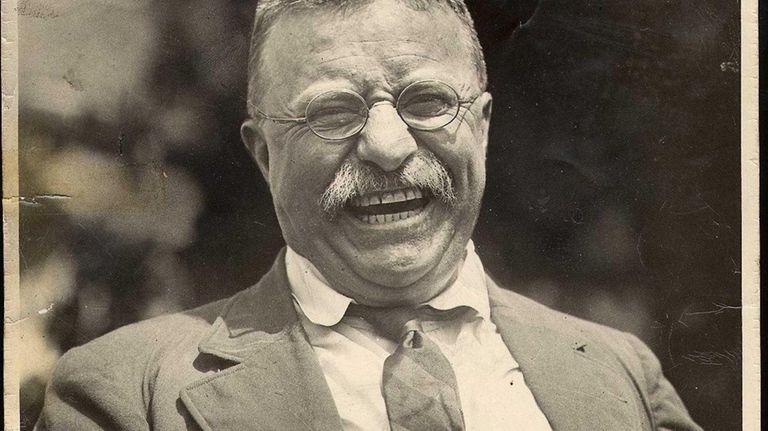

Theodore Roosevelt was known to capitalize the word “nature,” so it’s no surprise that when the 26th president took over the White House he brought with him a virtual zoo.

The Roosevelt sanctuary included a small bear named Jonathon, a pig named Maude, a lizard named Bill, several guinea pigs, a badger, a “one-legged” rooster, a barn owl, a hen, a hyena, a calico pony, and a blue macaw named Eli Yale, who flew in the White House conservatory, but often flew in the halls too.

(The origin of the bird’s name comes from Eilhu Yale, an 18th Century British Merchant, and the the namesake of Yale University. “Eli” is an informal name given to Yale graduates. Teddy was a Harvard man but admired the Yale School of Forestry, an institution founded by friend and fellow conversationalist Gifford Pinchot, a 1889 Yale grad).

Teddy was especially fond of Eli because it had a reputation of being noisy and ornery to the staff. This pleased the president immensely. “Eli has a bill that could bite through a boiler plate,” the president delightfully warned.

In 1902, when the White House conservatory was being repaired, Eli was said to be in a rage. “The President’s bird has not hesitated to use some choicest terms on [the workers] whenever they encroached upon her premises,” the papers reported.

In 1909, when Roosevelt and the animals left the White House, the conservatory would soon be gone too. That same year, President William Howard Taft tore it down to extend the West Wing.

The current Oval office resides there today.

Wash Your Hands? In the 19th Century it was ‘Please Take a Bath’

By Ken Zurski

In 1902, psychologist and chemist, William Thomas Sedgwick released a book titled Principles of Sanitary Science and Public Heath which was a compilation of lectures he gave as a professor of biological sciences at MIT. In it, Sedgwick extolled the virtues of good personal hygiene to keep infectious diseases away. “The absence of dirt,” he urged, “is not merely an aesthetic adornment.”

Basically, he was telling everyone to clean up. In essence, please take a bath.

Sedgwick was onto something. Until then taking a bath, for example, was an option most people chose to ignore. That’s because for centuries, cleanliness was seen as a sign of weakness or impurity. In some ancient religious philosophy’s, being wet, or letting the water touch you, was akin to allowing the devil enter your body. And in other circles, bathing was considered a sign of sexual mischievousness. Queen Isabella of Castile bragged that she took a bath only twice in her life, on her birth day and her wedding night. And Saint Benedict, an English monk who lived a solitary and monastic life, said “bathing shall seldom be permitted.”

Of course that was a long time ago when attitudes were based on god fearing principles, not logic. But even at the turn of the 20th century, personal hygiene was still somewhat taboo.

Sedgwick though wasn’t the first to encourage others to get well by getting clean. Benjamin Franklin, a man of many titles, was also an early advocate of good hygiene habits.

As America’s first diplomat in France, Franklin thoroughly enjoyed the pleasures of taking a bath, a European luxury, although his desires may have been influenced more by the pretty French maids who administered it. “I have never remembered to have seen my grandfather in better health,” William Temple Franklin wrote to a relative. “The warm bath three times a week have made quite a young man out of him [Franklin was in his 70’s at the time]. His pleasing gaiety makes everybody love him, especially the ladies, who permit him always to kiss him.” Regardless of his reasons for actually taking a bath, Franklin couldn’t help but get clean, right?

However, when a large tub of warm water wasn’t present, Franklin liked to take what he called “air baths.” Franklin thought being inside and cooped up in a germ infested, walled, and shuttered space, was the reason he got colds. So to keep from getting sick, Franklin would open the windows and stand completely naked in front of it. Ventilation was the key to prevention, he explained, although others likely weren’t so emboldened.

In the mid 19th century, bathtubs were heavy and costly and those who could afford it used it as much for decoration as for its intended purpose.

Before indoor plumbing, a large tub may have been made of sheet lead and anchored in a box the size of a coffin. Later bathtubs became more portable. Some were made of canvas and folded; others were hidden away and pulled down like a Murphy Bed. They were called “bath saucers.”

It wasn’t that most people didn’t understand the merits of taking a bath. It was just a chore to do so. Water had to be warmed and transported and would chill quickly; then dumped. Oftentimes families would use the same bath water in a pecking order that surely forced the last in line to take a much quicker dip than the first.

In the later half of the 19th century, as running water became more common, bathtubs became less mobile. Most were still bulky, steel cased and rimmed in cherry or oak, but stationary. Fancy bronzed iron legs held the tub above the floor.

Ads from the time encouraged consumers to think of the tub as something other than just a cleaning vessel. “Why shouldn’t the bathtub be part of the architecture of the house?” the ads asked. After all, if there is going to be such a large object in the home, it might as well be aesthetically pleasing.

Getting people to actually use it, however, that was another matter.

Sedgwick had medical reasons to back up his claims. As an epidemiologist, he studied diseases caused by poor drinking water and inferior sanitation practices. Good scientific research, he implied, should be all the proof needed. But attitudes and decades old habits needed to change too. “It follows as a matter of principle,” Sedgwick wrote, “that personal cleanliness is more important than public cleanliness.” He had a point. Largely populated cities were dirty messes, full of billowing black smoke from factories, coal dust, and discarded garbage and waste. Affixing blame for such conditions was more popular than actually doing something about it. Sedgwick focused on self-awareness to make his point. “A clean body is more important than a clean street,” he stressed.”Sanitation alone cannot hope to effect these changes. They must come from scientific hygiene carefully applied throughout long generations.”

People, it seemed, had to literally be scared into taking a bath.

Something Sedgwick understood, but fought to amend.

“Cleanness,” he wrote in concession, ”was an acquired taste.”

In March 1868, Three Years After the War, Mary Logan (the General’s Wife) Visited Richmond…

By Ken Zurski

General John A. Logan could not go.

“Blackjack Logan” as his men affectionately dubbed him due to his strikingly dark hair and eyes, was invited by a newspaper man in Chicago, Charles Wilson, to visit Richmond, Virginia.

It was March 1868, and Logan now the leader of the Grand Army of the Republic was too busy in the nation’s capital overseeing veteran’s affairs to break away. But Wilson had invited the entire Logan family with him on the trip. So he insisted Logan’s wife Mary, daughter Dolly and baby son, John Jr. still attend

The general gave them his blessing.

In Richmond, Mary Logan was prepared for the worse. Large portions of the city had been destroyed by fire and now three years removed from the brutality of war, it still resembled a battleground. “Driving from place to place we were greatly interested and realized more than we ever could have, had we not visited the city immediately after the war, the horrors through which the people of the Confederacy had passed,” Mary recalled after arriving.

Because of its proximity to Washington, many Union leaders, including President Lincoln, toured Richmond shortly after the North captured the embattled Southern capital. Lincoln arrived with his son Tad on April 4, 1865 to a military-style artillery gun salute. He viewed first hand the devastation caused by the fires set by the escaping Rebels. The city’s structures were nearly gone, but the war was over. Five days later, General Robert E Lee signed surrender papers. Less than a week after that, Lincoln was dead.

But Richmond survived.

“The hotel we stayed in was in a very wretched condition,” Mary would later write about her trip. “And we expected to find the rebellion everywhere.” Wilson, another war veteran, was interested in seeing Libby prison, so they took a carriage to the site. Along the roads, Mary noticed people still picking up the remnants of exploded shrapnel, broken cannon and Minie balls to sell for iron scrap at local foundries. She remembers passing a poor little boy, so “thinly clad that he had little to protect him for the inclemency of the weather.” The March chill had given the city a depressing glumness.

“Well isn’t it so miserably hot to-day,” Mary recalls the boy humorously calling out to the driver, while at the same time, “his teeth were chattering,” she wrote.

The carriage then made its way to the cemeteries.

This is where Mary took pause. Not only were there endless lines of stones, but they were all decorated. Mary was moved by the site. “In the churchyard we saw hundreds of graves of Confederate soldiers. These graves had upon them bleached Confederate flags and faded flowers and wreaths that had been laid upon by loving hands.” Mary stopped to reflect. “I had never been so touched by what I had seen,” she said.

When she returned to Washington, Mary summoned her husband and told him what she had witnessed at the grave sites. General Logan said that it was a beautiful revival of a custom of the ancients preserving the memory of the dead. “Within my power,” he promised her, “I will see that the tradition is carried out for Union soldier as well.” A promise he did not wait long to keep.

Almost immediately, Logan sent a letter to the adjunct- general of the Grand Army of the Republic, dictating an order for the first decoration of the graves of Union soldiers. He wrote:

The 30th day of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance no form or ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit.

On May 30, just as Logan had ordered, the first Decoration Day, now more commonly known as Memorial Day, took place at Arlington Cemetery.

‘Anyone Hear a Plane Crash?’ Flying the Air Mail Over Illinois was Lucky Lindy’s Most Dangerous Job

By Ken Zurski

Shortly before Charles Lindbergh became the most famous person in the world, he flew U.S. Air Mail flights over Illinois in a route from St Louis to Chicago.

At the time, the air mail pilot was considered “the most dangerous job in the country” due to the plane’s limitations and unpredictable weather. Instrument flying was not yet perfected and oftentimes the pilots would fly into situations where the only recourse was to ditch the plane.

This happened to Lindbergh several times, including one night over Peoria…

Charles Lindbergh was falling head first when he pulled tightly on the rip cord and hoped for the best. Suddenly the risers whipped around with a jerk and the free falling weight at the bottom of the harness snapped back into an upright position. The chute was open. But a more precarious threat lay just below. Lindbergh placed the rip cord in his pocket and took out a flashlight. He pointed it downward. “The first indication that I was near ground was a gradual darkening of the space below,” he recalled.

Time was running out.

Just minutes before, in desperation, Lindbergh was flying in circles over Peoria, Illinois looking for a place to land. It was around 8 p.m. on November 3, 1926. A fueling mistake in St. Louis had drained the main tank of the refurbished Army DeHavilland sooner than expected and the reserve tank was just about tapped. An early November snow was falling and visibility of ground lights was less than a half-mile. The Peoria airstrip was only faintly visible. “Twice I could see lights on the ground and descended to less than 200 feet before they disappeared from view.”

With only minutes left in the reserve, Lindbergh steered the craft east hoping to find a clearing in the weather, but it was too late. At least he had made it to a less populated area. “I decided to leave the ship rather than land blindly.” So he jumped.

The snow had turned to a light rain and the water-logged chute began to spin. It was too foggy to see but he could sense it. The ground was closing in. Then the chute stopped spinning just long enough to slow the descent. “I landed directly on a barbed wire fence without seeing it,” Lindbergh remembers.

Expecting the worst, he opened his eyes surprised to be unharmed. The fence helped break the fall and the thick khaki aviation suit kept the barbs from penetrating the skin. There wasn’t a scratch. Lindbergh took his bundled parachute in hand and headed towards the nearest light. He found a road and followed it to a small town. From there he would try to determine where his plane ended up.

B.K. (Pete) Thompson, a farmer, had just entered the town’s general store and was sitting down to a friendly game of cards when a “tall, slim man” walked in.

“Anyone hear a plane crash?” the stranger asked. Thompson offered to help.

Together the two men, similar in age (early 20’s), climbed into the farmer’s Model T to search the country roads. “I’m an airmail pilot,” the stranger told Thompson and introduced himself. Thompson told Lindbergh he was in Covell, Illinois, about seven miles west of Bloomington. “I ran out a fuel over Peoria,” Lindbergh explained.

The search for wreckage was fruitless; it was too dark. “Can you give me a ride to the train station?” Lindbergh asked. The plan was to take a train to Chicago and a fly a new plane over the area in the morning. The ten-mile drive on the dark bumpy roads was treacherous and Lindbergh buckled down for the ride. “For a man who had just ditched an airplane,” Thompson recalled. “He sure held on for dear life.”

If you find the wreckage, Lindbergh explained, there is a 38-caliber revolver in the cockpit. “Guard the mail,” he told Thompson.

Thompson found the wreckage the next day less than 500 feet south of his house. The plane’s main landing gear had torn off at impact. The wings were completely gone but the metal frame of the fuselage and tail were still intact. One wheel had broken loose and covered a full hundred yards before crashing through a fence and resting – fully inflated – against the wall of a hog house.

The revolver was still there; right where Lindbergh had said it would be. And three large U.S. Air Mail bags were on board too – one was split open and slightly oiled, but still legible.

Around mid-morning, the whir of an engine was heard overhead. It was Lindbergh. He landed the reserve plane in a field next to the wreckage and was treated to a fried chicken lunch “with all the trimmings” before loading up the airmail bags and heading back to Chicago to complete his route – some 24 hours late. But even the return trip was hampered by delays. “We spent about two hours trying to get the new plane started,” Thompson recalls. “Lindbergh and I keep pulling the propeller, but it must have been too cold.” Lindbergh had an idea. He went to the farmhouse and boiled 20 gallons of water to heat the radiator.

“The engine kicked right over,” Thompson said.

Thompson never saw the slim man again face-to-face, but would read about his heroics in the paper the following year. That’s when he remembered what the young pilot had told him on the automobile trip to the train station that night. An idea Lindbergh had considered just months before on another mail run over Peoria. While flying placidly through the clouds, Lindbergh mused over the question of balancing weight, fuel and distance and found an answer. “It can be done and I’m thinking of trying it,” he said.

Of course he was talking about crossing the Atlantic.

(Sources: Charles Lindbergh. “Spirit of St Louis” & “We;” A. Scott Berg. “Lindbergh;” Marion McClure. “Bloomington, Illinois Aviation- 1920, 1930, 1940.”)

‘Tobor the Great’ Was a Man-made Mechanical Movie Star

By Ken Zurski

In The fall of 1954, a new movie titled “Tobor the Great” was released in theaters. It was billed as “a science fiction film for kids” and Tobor “a man-made monster filled with every human emotion.”

In the film, Tobor is a fabricated astronaut who can “live where no human can breathe.” He is befriended by 11-year-old Brian, nicknamed “Gadge,” who together battle Soviet agents who want Tobor for themselves.

“Gadge” is taken hostage, but using his emotions, summons Tobor who arrives to save the day by carrying the boy to safety in his clunky arms.

The movie had no name actors and was shot in less than a month. Still kids adored the mechanical Tobor and parents appreciated the heartwarming ending. Critics were mostly kind, evoking a child’s sensibilities in their approval: “To say children will be delighted by this brand new science fiction adventure would be putting it ‘Super Sonic,’” as one reviewer put it.

In Florida at Miami’s Embassy Theater the movie played as a double-bill with another kids film, “Roogie’s Bump,” about a boy’s love for baseball and a heavenly visit from a deceased ballplayer.

“Tobor is filled with lots of scientific chatter in its early reels,” wrote the Miami Herald, “but builds up to a faster pace as the robot comes to the rescue in the final reels.”

The kids featured in the movies are so smart and well-behaved that the Herald reviewer joked: “Patrons of the Embassy can hardly be held accountable if they view the double-bill and go home and beat their normal, average children.”

Today “Tobor the Great” is considered low budget and schlocky and filled with “terrible acting and dialogue.” A contemporary audience on RottenTomatoes.com rates it at 50-percent on the Tomatometer. “This is one of those movies which makes robots seem less scary and more like friends,” goes one positive audience reviewer. Another called it “corny” and “bland.”

None of that mattered to kids in 1954. For months after the movie’s release, Tobor giants were seen throughout larger cities making appearances and holding children aloft just like in a movie.

Tobor toys filled the shelves, including a popular remote-controlled model.

Perhaps the acceptance of the film was due in part to its ingenious title.

The fun was in Tobor’s distinctive name.

Spell it backwards and you discover that Tobor is no “monster,” as the ads suggest, but a simple robot – and a gentle one at that.

Gene Autry’s Forgotten Christmas Song is One You May Already Know

By Ken Zurski

In 1951, cowboy crooner Gene Autry released a song titled “The Three Little Dwarfs,” that playfully told the story of three “helpers” trusted by Santa to “drive” his sleigh on Christmas Eve.

The song was written by Stuart Hamblen, a singer, songwriter and politician who ran for President of the United States in 1952 on the Prohibition Party ticket. “A cowboy singer, former racehorse owner and converted alcoholic,” Time magazine wrote that year about Hamblen who picked up 73,000 votes, second most by a third party candidate.

Before politics, the Texas born Hamblen was known for being one of the first singing cowboys and in the 1930’s hosted a popular radio show called “Family Album.”

Hamblen wrote several hits for country radio but nothing quite as enduring as “The Three Little Dwarfs.”

The most famous singing cowboy, Gene Autry recorded the song and released it as a single with a B side tune titled “32 feet – 8 Little Tails.” In December 1951, Columbia Records ran an ad in Billboard listing the label’s “best sellers.” Autry’s “The Three Little Dwarfs” was listed just ahead of his version of “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer.”

Today, Autry’s version of “Rudolph” is considered a holiday staple, while “The Three Little Dwarfs” is mostly forgotten.

The song itself however is not.

It was immortalized in a two-minute stop-animation cartoon titled “The Three Little Dwarfs,” but more commonly known as “Hardrock , Coco and Joe.”

Oh-lee-o-lay-dee, o-lay-dee-I-ay

Donner and Blitzen, away, away

Oh-lee-o-lay-dee, o-lay-dee-I-oh

I’m Hardrock! I’m Coco! I’m Joe!

The short premiered on Chicago’s WGN-TV on Christmas Eve 1956.

Autry’s song was not the one used in the short. The tune was re-recorded and reworked. For instance, a narrator is used to speak some of words rather than sing them.

But the most recognizable difference was in Joe’s line. In Autry’s rendition, Joe is sung in a high-pitched voice rather than the distinctive and memorable deep bass of “I’m Joe” featured in the animated version.

Benjamin Franklin and the Turkey

By Ken Zurski

It’s hard to imagine anything other than the majestic bald eagle as the symbol of the United States of America. But back in the late 18th century, when good and honorable men were deciding such things, there were several considerations, mostly other animals, vying for a symbol which best represented the new country.

Was the turkey one of them?

Perhaps, but it wasn’t Benjamin Franklin who nominated the turkey, as some history lessons would later suggest. Franklin’s choice for America’s national symbol was much different than both the bald eagle and the turkey.

He did however admire the turkey.

Here’s the backstory:

In 1783, a year-and-half after Congress adopted the bald eagle as the symbol of America, Franklin saw the image of the bird on the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati of America, a military fraternity of revolutionary war officers. He thought the drawing of the bald eagle on the badge looked more like a turkey, a fair and reasonable complaint considering the image looked like, well, a turkey.

But it was the use of the bald eagle as the symbol of America that most infuriated Franklin. “[The bald eagle] is a bird of bad moral character,” he wrote to his daughter. “He does not get his Living honestly.”

It was a a matter of principal for Franklin. The bald eagle was a notorious thief, he implied. He had a point. Considered a good glider and observer, the bald eagle often watches other birds, like the more agile Osprey (appropriately called a fish hawk) dive into water to seize its prey. The bald eagle then assaults the Osprey and forces it to release the catch, grabs the prey in mid-air, and returns to its nest with the stolen goods. “With all this injustice,” Franklin wrote as only he could, “[The bald eagle] is a rank coward.”

Franklin then expounded on the turkey comparison: “For the truth, the turkey is a much more respectable bird…a true original Native of America who would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his farmyard with a red coat on.”

Franklin’s suggestion of the turkey as the nation’s symbol, however, is a myth. He never suggested such a thing. He only compared the bald eagle to a turkey because the drawing reminded him of a turkey. Franklin’s argument was in the choice of the bald eagle and not in support of the turkey, an idea he called “vain and silly.”

Some even claim his comments and comparisons were slyly referring to members of the Society, of whom he thought was an elitist group comprised of “brave and honest” men but on a chivalric order, similar to the ruling country to which they helped defeat. This might explain why Franklin’s assessment of the bald eagle in the letter is based solely on human behavior, not a bird’s.

Perhaps when Franklin made the disparaging comments against the bald eagle he was also harboring a nearly decade old grudge.

In 1775, a year before America’s independence, Franklin wrote the Pennsylvania Journal and suggested an animal be used as a symbol of a new country, one that had the “temper and conduct of America,” he explained. He had something in mind. “She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders;” he wrote. “She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage”

Eventually the image Franklin suggested did appear on a $20 bill issued in 1778, adopted for use as the official seal of the War Office, and may have been the inspiration for the Gadsden flag with the inscription, “Don’t Tread On Me.”

But it never officially became the preferred symbol of the new country.

That belongs to the bald eagle.

Franklin’s choice: the rattlesnake.

Gold Ring: The Original ‘Black Friday’ Goes Back 150 Years

By Ken Zurski

Before Americans began rushing to stores the day after Thanksgiving and calling the shopping frenzy, “Black Friday,” the term itself was used to describe a dark and devious part of our nation’s history.

Here’s the story:

The original “Black Friday” begins with a man named Jay Gould.

A leather maker turned New York railroad owner, Gould was the youngest of six children, the only boy, and a scrawny one at that; growing up to be barely five feet tall. What he lacked in size, however, he made up for in ambition.

A financial whiz even as a young man, Gould started surveying and plotting maps for land in rural New York, where he grew up. It was tough work, but not much pay, at least not enough for Gould. In 1856 he met a successful tanner – good work at the time – who taught Gould how to make leather from animal skins and tree bark. Gould found making money just as easy as fashioning belts and bridles. He found a few rich backers, hired a few men and started his own tanning company by literally building a town from scratch in the middle of a vacant but abundant woodland. When the money started to flow, the backers balked, accusing Gould of deception. Their suspicions led to a takeover. The workers, who all lived quite comfortably in the new town they built and named Gouldsborough, rallied around Gould and took the plant back by force, in a shootout no less, although no one was seriously hurt.

Gould won the day, but the business was ruined. By sheer luck, another promising venture opened up. A friend and fellow leather partner had some stock in a small upstate New York railroad line. The line was dying and the stock price plummeted. So Gould bought up the stock, all of it in fact, with what little earnings he had left, and began improving the line. Eventually the rusty trail hooked up with a larger line and Gould was back in business. He now owned the quite lucrative Erie Railroad.

Ten years later, in 1869, Gould got greedy and turned his attentions to gold.

Gold was being used exclusively by European markets to pay American farmers for exports since the U.S currency, greenbacks, were not legal tender overseas. Since it would take weeks, sometime months for a transaction to occur, the price would fluctuate with the unstable gold/greenback exchange rate. If gold went down or the greenback price went up, merchants would be liable -often at a substantial loss – to cover the cost of the fluctuations. To protect merchants against risk, the New York Stock Exchange was created so gold could be borrowed at current rates and merchants could pay suppliers immediately and make the gold payment when it came due. Since it was gold for gold – exchange rates were irrelevant.

Gould watched the markets closely always looking for a way to trade up. He reasoned that if traders, like himself, bought gold then lent it using cash as collateral, large collections could be acquired without using much cash at all. And if gold bought more greenback, then products shipped overseas would look cheaper and buyers would spend more. He had a plan but needed a partner.

He found that person in “Gentleman Jim Fisk.”

Jim Fisk was a larger than life figure in New York both physically and socially. A farm boy from New England, Fisk worked as a laborer in a circus troupe before becoming a two-bit peddler selling worthless trinkets and tools door to door to struggling farmers. The townsfolk were duped into calling him “Santa Claus” not only for his physical traits but his apparent generosity as well. When the Civil War came, Fisk made a fortune smuggling cotton from southern plantations to northern mills.

So by the time he reached New York, Fisk was a wealthy man. He also spent money as fast as he could make it; openly cavorted with pretty young girls; and lavished those he admired with expensive gifts and nights on the town. Fisk never hid behind his actions even if they were corrupt. He would chortle at his own genius and openly embarrass those he was cheating. He earned the dubious nickname “Gentleman” for being polite and loyal to his friends.

Fisk and Gould were already in the business of slippery finance. Besides manipulating railroad stock (Fisk was on the board of the Erie Railroad), they dabbled in livestock and bought up cattle futures when prices dropped to a penny a head. Convinced they could outsmart, out con and outlast anyone, it was time to go after a bigger prize: gold. There was only $20 million in gold available in New York City and nationally $100 million in reserves. The market was ripe for the taking and both men beamed at the prospects.

But the government stood in the way. President Grant was trying to figure out a way to unravel the gold mess, increase shipments overseas and pay off war debts. If gold prices suddenly skyrocketed, as Gould and Fisk had intended, Grant might consider a proposed plan for the government to sell its gold reserves and stabilize the markets; a plan that would leave the two clever traders in a quandary.

Through acquaintances, including Grant’s own brother-in-law, Gould and Fisk met with the president. In June of 1869, they pitched their idea posing as two concerned (a lie) but wealthy (true) citizens who could save the gold markets and raise exports, thus doing the country a favor. They insisted the president let the markets stand and keep the government at bay. Fisk even treated the president to an evening at the opera – in Gould’s private box. The wily general may have been impressed by the opera, but he was also a practical man. He told the two estimable gentlemen that he had no plans to intervene, at least not initially. But Grant really had no idea what the two shysters were up to.

A few months later, when Fisk sent a letter to Grant to confirm the president’s steadfast support, a message erroneously arrived back that Grant had received the letter and there would be no reply. The lack of a response was as good as a “yes” for Fisk. Grant was clearly on board, he thought.

He was wrong.

On September 20th, a Monday, Fisk’s broker started to buy and the markets subsequently panicked. Gold held steady at first at $130 for every $100 in greenback, but the next day Fisk worked his magic. He showed up in person and went on the offensive. Using threats and lies, including where he thought the president stood on the matter, Fisk spooked the floor.

The Bulls slaughtered the Bears.

Gold was bought, borrowed and sold. And Fisk and Gould, through various brokers, did all the buying. On Wednesday, gold closed slightly over 141, the highest price ever. In his typical showy style, Fisk couldn’t help but rub it in. He brazenly offered bets of 50-thousand dollars that the number would reach 145 by the end of the week. If someone took that sucker proposition, they lost. By Thursday, gold prices hit an astounding 150. The next day it would reach 160.

Then the bottom fell out.

At the White House, Grant was tipped off and furious. On September 24, a Friday, he put the government gold reserve up for sale and Gould and Fisk were effectively out of business. Thanks to the government sell off, almost immediately, gold prices plummeted back to the 130’s. Many investors lost a bundle, but the two schemers got out mostly unscathed.

The whole affair became famously known as “Black Friday.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Steely Dan

In 1975, Steely Dan, the rock group consisting of multi-instrumentalist Walter Becker and singer Donald Fagen, wrote a song titled ‘Black Friday” and released it that same year as the first single off their album “Katy Lied.” The song reached #37 on the Billboard charts.

When Black Friday comes

I stand down by the door

And catch the grey men when they

Dive from the fourteenth floor

The band confirmed that the song is about the 1869 Gould/Fisk takeover but that it also has odd references that have nothing to do with the original story. For instance, an Australian town named Muswellbrooke (“Fly down to Muswellbrook”) is mentioned…and then there is the line about kangaroos (“Nothing to do but feed all the kangaroos”).

Fagen later confirmed in an interview the town name was added by chance: “I think we had a map and put our finger down at the place that we thought would be the furthest away from New York or wherever we were at the time. That was it.”

Today the term “Black Friday” is referenced in relation to the Friday after Thanksgiving and traditionally the busiest shopping season of the year. The day retailers go “in the black,” so to speak.

Steely Dan had none of that in mind when they wrote the song.

The Gettysburg Address We Don’t Remember

The beginning and final sentences of Edward Everett’s speech on November 19, 1863 at the dedication of Gettysburg’s National Cemetery:

“STANDING beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature..

..But they, I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country there will be no brighter page than that which relates THE BATTLES OF GETTYSBURG.”

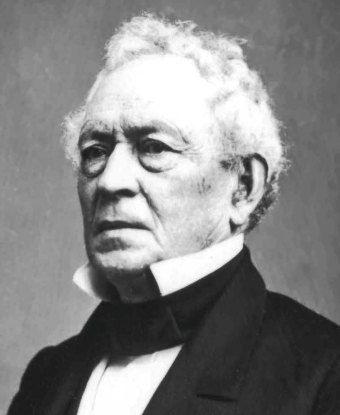

The Boston orator was the obvious choice for the occasion. During his 40-year career as professor, diplomat, and statesman, he had consistently dazzled audiences with his brilliant oratory. On November 19 in Gettysburg, Everett held the crowd “spellbound” for nearly two hours. But his words are not the ones that are remembered today.

Shortly after Everett’s speech, President Abraham Lincoln spoke for less than three minutes.

The following is from Ted Widmer, “The Other Gettysburg Address” New York Times http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/…/the-other-gettysbu…/…

“Edward Everett had spent his life preparing for this moment. If anyone could put the battle into a broad historical context, it was he. His immense erudition and his reputation as a speaker set expectations very high for the address to come. As it turned out, Americans were correct to assume that history would forever remember the words spoken on that day. But they were not to be his. As we all know, another speaker stole the limelight, and what we now call the Gettysburg Address was close to the opposite of what Everett prepared. It was barely an Address at all; simply the musings of a speaker with no command of Greek history, no polish on the stage, and barely a speech at all – a mere exhalation of around 270 words. Everett’s first sentence, just clearing his throat, was 19 percent of that – 52 words. By the time he was finished, about 2 hours later, he had spoken more than 13,000.”

(Quotes and text culled from various internet sources including http://www.massmoments.org)

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 35

- Next →