History

A Salute to the Hand Salute – How Far Back Does it Go?

By Ken Zurski

In 1833, an Irish-born English artist named William Collins exhibited an oil on wood painting he appropriately titled, Rustic Civility. In the colorful image, three children are seen near a wooden gate that blocks the path of a dirt road. Collins shows the gate has been opened, presumably by the children. A boy is propped up against the open gate securing it’s place. Another smaller child cowers by the boy’s side. Yet another looks straight ahead from behind the gate.

But why and for whom did the children open the gate?

Well, that’s just a part of the painting’s mystique or as one art connoisseur wisely describes, “its puzzle.”

Upon closer inspection, however, the “puzzle” appears to be solved.

Most obvious is the shadow near the children’s feet. It is a partial outline of a horse and upon its back a rider in a brimmed hat. The children have opened the gate to make it easier for the rider, probably a stranger to them, to pass.

“People are amused at having to find out what is coming through the gate, which few do, till the shadow on the ground is pointed out to them,” the sixth Duke of Devonshire noted after buying the curious painting for his collection.

The work in some circles has been wrongly classified as a children’s picture. True, Collins would specialize in putting children in his paintings, but they were not specifically made for children. “Rustic” was part of his repertoire and a theme for several paintings including Rustic Hospitality, where friendly villagers welcome a wayward traveler who has stopped to rest near their cottage.

Today, most of Collins works are in London museums. His representations of English countryside charm in the early 19th century were very popular. Rustic Civility, however, seems to be remembered for a more significant and historical reasons. The young boy in the painting is holding his hand to his head in a gesture that closely resembles what we know today as a military salute.

A gesture not yet so easily defined at the time.

According to various sources, the origins of the hand salute goes back to medieval times when knights would salute one another by tipping their hats. Since their heads were covered with heavy and cumbersome armor, oftentimes they would just raise the visor in recognition.

In the Revolutionary War, British soldiers would remove or raise their hats in the presence of a ranking officer, an easy task since head gear at the time was used as decoration only and made of lighter material.

In subsequent wars, when soldier’s helmets became more protective the act of actually removing the head gear was too risky. A simple hand raise to the brow would suffice.

By the 20th century and during the two World Wars, saluting became more streamlined and distinctive, with the hands either palm out (the European version) or palm flat and down, the American preference.

Regardless of its history, Collins is credited at least with featuring a salute, albeit slyly, in his painting Rustic Civility. The boy appears to be “tugging his forelock,” an old-worldly expression of high regard and a gesture that suggests an early incarnation of the modern day hand to forehead signal.

This inclination of course is a matter of opinion. Perhaps, as others might suggest, the boy is just shading his eyes. After all, the location of the shadowed horse and rider puts the perspective of the sun’s light directly in the boy’s path. However, in close up, it does appear as though the boy is grabbing a lock of hair.

This clearly supports the salute theory.

Unfortunately, by the time any serious debate was raised, Collins, the artist, was dead.

So in historical context, let’s give the painter his due: To open a wooden gate while on horseback is a difficult thing to do. The children helped the man by opening the gate. The boy then saluted in deference – or civility as the title suggests.

A sign of a respect for an elder in need, Collins likely implied.

And respect is what the “salute” stands for today.

When The World Met Queen Marie of Romania

By Ken Zurski

In the summer of 1919, King Ferdinand of Romania sent his British born wife Queen Marie to Paris to attend the Treaty of Versailles, a historic meeting of allied leaders designed to form a peace treaty and draw a new map of Europe at the end of the First World War.

“My God, I simply went wherever they called me,” the Queen said, stating the obvious.

The glamorous Marie did more than just attend. She hobnobbed with the press, flirted with world leaders, including the Big Four (Italy, England, France and the U.S.), and although she had an important job to do for her country, found time to go on lavish shopping sprees too.

By the time the historic Treaty was over, everyone knew a little bit more about the outlandish Queen Marie. And thanks in part to her unorthodox efforts, Romania, at least on paper, had doubled in size.

Born into royalty as Princess Marie of Edinburgh in 1875 in Kent, England, Marie was the eldest daughter of her mother also named Marie, the only surviving child of Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and Alexander, the second son of Queen Victoria and a naval officer who moved the family extensively throughout her childhood. The Princess was a good catch, even as a youth, and gentleman came calling for her including a first cousin George (later George V of England) who professed his love for Marie, but was turned away.

In 1893, at the age of 18, Marie married Ferdinand, a third cousin, who by default, was the heir to the Romanian throne. King Carol I, Ferdinand’s uncle, and his wife had only one daughter so the succession fell to his brother Leopold, who renounced his rights in 1880. Leopold’s son did the same in 1886. So even before the turn of the 20th century, Ferdinand was the heir-presumptive. In 1916, when Carol died, Ferdinand became the King and Marie the Queen of Romania.

Marie was a different kind of Queen, less submissive and daringly independent. During the start of World War I, Marie spent time with the Red Cross in hospitals risking her own life in the disease filled tents. Although she was British born, she had great respect for the Romanian people and would venture into the countryside unaccompanied by guards. Many villagers crowded her in adulation; kissing her hands and falling down at her feet. “At first it was difficult unblushingly to accept such homage,” she wrote, “but little by little I got accustomed to these loyal manifestations; half humbled, half proud, I would advance amongst them, happy to be in their midst.”

In contrast to Marie’s adventurist spirit her husband, the King, was far less dynamic. Quiet and shy and as one writer described “stupid” too, Ferdinand’s most enduring feature was his ears which stuck out the sides of his head like a teddy bear. He said little and mattered even less.

Marie, however, was the complete opposite. Pretty and intelligent she spoke out when asked and seemed to have a good knowledge of foreign affairs. She also had little interest in being a committed wife. Blaming a loveless marriage, she was boldly unfaithful and found multiple lover’s in dashing figures like a Canadian millionaire miner from the Klondike. (In her later years, rumors abounded that one of her longstanding paramours, the nephew of Romania’a Foreign Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu, was the father of her children (six in all, three girls) except for the one that eventually became a bad King. That one was Ferdinand’s, went the biting accusation.)

In November of 1918, when war activities ended, Marie was the outspoken one not her husband. Sending her to the Treaty in Paris instead was an obvious choice for the King, if unprecedented.

So Marie went and brought her three daughters along with her. Together they shopped, dined and were generally the life of any party they attended. The Queen wore out those who tried to follow her. She charmed her way to negotiations and gained admirers along the way. “She really is an unusual woman and if she was not so simple you would think she was conceited,” chimed the British Ambassador to France. David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, was just as forthright: “{Marie] is a very naughty, but a very clever woman.” he professed. Edward House, an American diplomat and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s chief adviser on European diplomacy and politics, was even more complimentary, calling her, “one of the most delightful personalities of all the royal women I have met in the West.”

Instead of being intimidated, which many had predicted, Marie intimidated others with her saucy manners and speech. In one instance, she invited herself to lunch with President Wilson, then showed up fashionably late with an entourage of ten in tow. “I could see from the cut of the President’s jaw,” one guest noted, “that a slice of Romania was being looped off.”

According to reports, Marie dominated the conversation. “I have never heard a lady talk about such things.” remarked Wilson’s traveling doctor. ” I honestly do not know where to look I was so embarrassed.”

In the end, Romania grew in size and population. In fact, of all the contributors at the conference, Romania is widely considered to have picked up the greatest gains, including Transylvania which became – and still is – a part of “Greater Romania.” King Ferdinand could only wait for word back home. He sent letters of encouragement and advice to his wife, which she mostly ignored.

“I had given my country a living face,” she said about her visit.

(Sources: Paris 1919 by Margret MacMillian; My Country by Queen Marie; various internet articles)

Not Just a Right to Vote, But A Right to Be Heard

By Ken Zurski

In July of 1848 a teenager named Charlotte Woodward read an announcement in a local newspaper about a group of women who would be meeting at a Methodist Church in Seneca Falls, New York, a modest wagon ride from her family’s farm near Syracuse. “A convention to discuss the social, civil and religious condition and rights of woman, “ the ad read. Woodward was intrigued.

In July of 1848 a teenager named Charlotte Woodward read an announcement in a local newspaper about a group of women who would be meeting at a Methodist Church in Seneca Falls, New York, a modest wagon ride from her family’s farm near Syracuse. “A convention to discuss the social, civil and religious condition and rights of woman, “ the ad read. Woodward was intrigued.

Woodward had been a school teacher at age fifteen but mostly worked at home, sewing gloves for merchants to sell. The work was long and the pay nearly nonexistent. This was the role of a woman at the time, no identity and no apparent social status other than tending to her family or husband’s needs and eventually having babies, oftentimes lots of them. A woman’s wages, if she worked, belonged to her spouse. She had no rights, no advantages. “She was her father’s daughter,” one writer stressed about the role of women in the mid 19th century, “until she became her husband’s wife.”

She was, however, protected by law against physical abuse, but only with “a stick bigger than a man’s thumb.” A punishment would be imposed, but no damages were ever awarded for injuries since no woman had the right to sign any legal documents.

Woodward was unmarried and feared no man, but she fumed at the prospects of working the rest of her life for others and eventually to a man she might be forced to wed, but did not love. “Every fiber of my being reveled, although silently, for all the hours that I sat and sewed gloves for a miserable pittance which, after it was earned, could never be mine.” Her interest in the women’s rights convention was more a revelation than a curiosity. “I wanted to work, but I wanted to choose my task and I wanted to collect my wages.”

So she went to Seneca Falls.

The convention was the brainchild of two women, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who attended the World’s Anti-Slavery Congress in London in 1840 as part of a women delegation, four in fact, and first of its kind. Their voices were mostly silenced. Some reports had the women turned away at the hall entrance. Returning home, Mott and Stanton gathered a lively group of women who discussed equality behind closed doors. In 1848, they felt it was time to take their case public. So they announced the convention’s date and invited anyone, even men, to come. Men could be part of the second day’s activities, the ad implied. “The first day would be exclusively for women.”.

Apparently, men didn’t care for rules not imposed by men. So on the first day, more than 50 lined up in front of the church. Some women were appalled, but Woodward recalls the men as “uncommonly liberal,” apparently meaning they had open, not closed minds. One man was proof of that. His name was Frederick Douglass.

But it wasn’t just men who were outside of the church that day. It was the women too. The church doors were locked and only the minister had a key. Apparently, the minister, who earlier approved the conference, had changed his mind after talking to the elders of the church, all men of course. As one story goes, the women stood on each other’s shoulders, managed to open a window shutter, climb inside, and open the doors. Nothing more was reported of the minister’s emphatic reversal after that.

Mott was a very good speaker, a rarity for a woman. Not that she was well-spoken, many were, but that she had the natural ability to express her views in front of a large audience. Public speaking was not something a woman could practice at the time. James Mott, her husband would hold order since by law, women could not. The ladies were there to change the laws, not break them.

By the end of the two days and nearly 18 hours of speeches, debates and readings, most of the women including Woodward signed a document titled “Declaration of Sentiments,” similar to the Declaration of Independence. The 1000 word document began with an opening statement that revised text from Thomas Jefferson’s original declaration and first sentence. It read: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal.” The two added words were obvious.

The statement ended this way:

“The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpation on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.”

And then came the point of the conference, the sentiments, or “facts.” These were the rules that must change. Among them were disapproval’s of common law, mostly taken for granted by men. “He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns,” read one. “He has compelled her to commit to laws in the formation by which she had no voice,” went another. “He has made her, in marriage, in the eyes of the law, civilly dead.”

Only one sentiment was a sticking point for the women. It read: “He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.” This was a social decalration, some argued, not a political one. The right to vote would likely get the least support from men. And besides, it might be the one sentiment that men were so strongly against that they would ignore all the others. After much debate, most of the women wanted the voting rights stricken from the document. But Frederick Douglass, a self-educated former slave, spoke in favor of its inclusion. “In this denial of the right to participate in government,” he eloquently stated, “not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the meaning and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government – of the world.”

Later, Susan B Anthony, who was not at the conference, would make voting rights the cornerstone of the suffragette movement, a debate that became more contentious after the Civil War ended and freed slaves also demanded the right to vote. Once again, Douglass was at the forefront. But it was not an easy sell, especially for women whose efforts to that point had been one frustrating roadblock followed by another.

In 1866, Anthony’s mouthpiece, the outspoken Stanton, went too far. She called former slaves “ignorant(s) and foreigners,” and chastised Douglass and others for putting blacks rights before a woman’s. Douglass, who to that point supported suffrage, angrily countered: “When women, because they are women, are hunted down…when they are dragged from their houses and hung upon lampposts, when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains dashed upon the pavement, when they are objects of insult and outrage at every turn, when they are in danger of having their homes burnt down over their heads…then they will have the urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own.” In the end, the Fifteenth Amendment was passed which included race, but not gender. In principle, blacks could vote, but not black women.

But that fight would come much later. In 1848, Douglass’ words about women being “one-half of the moral and intellectual power of government” rang true. The call for men to integrate women in elections was included in the “sentiments” and the resolution passed.

When it was over, most men were apathetic. Some sarcastically called the two days of meetings a “Hen Convention” and mocked the proceedings. “If there is one characteristic of the sex which more than another elevates and ennobles it,” one newspaper editor, obviously a man, wrote, “it is the persistency and intensity of a woman’s love for man. The ladies always had the best place and choicest tidbits at the table.”

But despite the protests, the convention sparked more debates, more meetings and a movement which would last for years.

Woodward had no idea how that day would change her. She eventually joined Anthony’s suffrage camp and spent the rest of her life fighting for the right to vote.

Finally in 1920, after the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment, she had the chance.

Sadly, though, she never got to cast that first – or any – ballot.

Charlotte Woodward Pierce, her married name, was the youngest to sign the “Declaration of Sentiments” and now some seven decades later, of the 68 women who participated in Seneca Falls, she was the sole survivor.

On election day 1920, she fell ill and stayed home. The next year, her eyesight went bad. “I’m too old,” she said. “I’m afraid I’ll never vote.”

That same year she died at the age of 92.

(Sources: Judith Wellman, Historian Historical New York; “The Scarlet Sisters: Sex, Suffrage, and Scandal in the Gilded Age” by Myra MacPherson)

The Poll That Picked FDR To Lose

By Ken Zurski

In 1920, starting with the election of President Warren G. Harding, a weekly magazine called The Literary Digest correctly picked the winner of each subsequent presidential election up to and including Franklin D. Roosevelt’s decisive victory over Herbert Hoover in 1932.

Quite an impressive track record by a magazine founded by two Lutheran ministers in 1890. The Literary Review culled articles from other publications and provided readers with insightful analysis and opinions on the day’s events. Eventually, as the subscriber list grew, the magazine created its own response-based surveys, or polling, as it is known today.

The presidential races were the perfect example of this system.

So in 1936, with a subscriber base of 10 million and a solid track record, the Digest was ready to declare the next president: “Once again, [we are] asking more than ten million voters — one out of four, representing every county in the United States — to settle November’s election in October,” they bragged.

When the tallies were in, the Digest polls showed Republican Alfred Landon beating incumbent Roosevelt 57-percent to 43-percent. This was a surprise to many who thought Landon didn’t stand a chance.

He didn’t.

Roosevelt was a progressive Democrat whose New Deal policies, like the Social Security Act and Public Pension Act, passed through Congress with mostly bipartisan support. Soon, millions of Americans burdened by the Great Depression would receive federal assistance.

Landon, a moderate, admired Roosevelt but felt he was soft on business and yielded too much presidential power. “I will not promise the moon,” he exclaimed during a campaign speech and warned against raising payroll taxes to pay for benefits. It didn’t work. Roosevelt won all but two states, Maine and Vermont, and sailed to a second term with 60-percent of the popular vote.

Even Landon’s hometown state of Kansas, where he had been Governor since 1933, went with the President. In the end, Landon’s 8 electoral votes to Roosevelt’s 532 – or 98-percent – made it the most lopsided general election in history.

In hindsight, poor sampling was blamed for the Digest’s erroneous choice. Not only were subscribers mostly middle to upper class, but only a little over two of the ten million samples were returned, skewing the result.

The big winner, however, besides Roosevelt, was George Gallup, the son of an Iowa dairy farmer and eventual newspaperman, whose upstart polling company American Institute of Public Opinion correctly chose the President over Landon to within 1 percent of the actual margin of victory.

In 1948, the validity of public opinion polls would be questioned again when Gallup incorrectly picked Thomas Dewey to beat Roosevelt’s successor by death, Harry S.Truman.

Since it was widely considered Truman would lose his reelection bid to a full term, Gallup survived the scrutiny.

Even the Chicago Tribune got it wrong, claiming a Dewey presidency was “inevitable,” and printing an early edition with the now infamous headline of “Dewey Defeats Truman.” A humiliation that Truman mocked the next day.

The Literary Digest, however, had no say in the matter.

In 1938, the magazine merged with another review publication and stopped polling subscribers.

The Bee Man

By Ken Zurski

When Amos Root was a boy growing up on a farm in Medina, Ohio, instead of helping his father with the chores he stuck by his mother’s side and tended to the garden instead.

Root was small in size (only five-foot-three as an adult) and prone to sickness. The garden work suited him just fine. But in his teens, for money, Root took up jewelry as a trade and became quite good at it.

Then in 1865, at the age of 26, he found his calling – bees.

Root had offered a man a dollar if he could round up a swarm of bees outside the doors of his jewelry store. The man did and Root was hooked. But Root didn’t want to just harvest bees, he wanted to study them.

Eventually his work led to a national trade journal titled Gleaning’s in Bee Culture. Bees became his business and profitable too, but Root had other interests as well, specifically mechanical things, like the automobile, a blessing for someone who hated cleaning up after the horse. “I do not like the smell of the stables,” he once wrote.

But the automobile was different. “It never gets tired; it gets there quicker than any horse can possibly do.”

He bought an Oldsmobile Runabout, “for less than a horse” he bragged, and happily drove it near his home. Then in September 1904, at the age of 69, Root took his longest trip yet, a nearly 400-mile journey to Dayton, Ohio. Root had heard a couple of “minister’s sons” were making great strides in aviation, so he wrote them and asked if he could take a look. His enthusiasm was evident.

He bought an Oldsmobile Runabout, “for less than a horse” he bragged, and happily drove it near his home. Then in September 1904, at the age of 69, Root took his longest trip yet, a nearly 400-mile journey to Dayton, Ohio. Root had heard a couple of “minister’s sons” were making great strides in aviation, so he wrote them and asked if he could take a look. His enthusiasm was evident.

The two brothers granted his wish, but only if he promised not to reveal any secrets. In August of 1904, Root set off for his first trip to Dayton and the next month did the same. The first visit he watched in awe, but revealed nothing. The second time he was given permission to write about what he had seen. It was the first time the Wright brothers and their flying machine appeared in print.

“My dear friends,” Root gleefully wrote in his bee publication, “I have a wonderful story to tell you. “

Slam Bradley and the Evolution of Superman

By Ken Zurski

In January of 1933, a short story titled “The Reign of the Super-Man.” appeared in a science fiction fanzine created by two teenagers at the time, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel.

The “Superman” or title character of their story was a bad guy with a bald head and telepathic powers.

“The Superman theme has been one of the themes ever since Samson and Hercules; and I just sat down and wrote a story of that type – only in this story, the Superman was a villain,” Siegel later explained in an interview.

Eventually the two friends decided Superman would be better as a good guy. But they weren’t sure how to make the transition. So they drew up another character named Slam Bradley. “Jerry came up with the idea of a man of action with a sense of humor,” Shuster relates. “Still, he couldn’t fly, and he didn’t have a costume.”

Actually the concept of Slam Bradley, including the name, is credited to Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, an avid horse rider and one of the youngest cadets to join the US Calvary in 1917 at the age of 27. Wheeler-Johnson was commissioned a major in World War I. When the war ended, Wheeler-Nicholson openly wrote letters to president Warren G. Harding describing mistreatment by senior officers at West Point. The accusations led to counter charges, lawsuits and a court martial trail conviction of Wheeler-Johnson for violating the 96th Article of War which essentially prohibits public criticism of the military by an officer.

Wheeler-Nicholson resigned from his duties in 1923 and became a pulp writer and entrepreneur instead. While looking for a distinctive character to highlight his new Detective Comics series, he sent a letter to Seigel. “We want a detective hero called ‘Slam Bradley’ he wrote. “He is to be an amateur, called in by the police to help unravel difficult cases.”

Wheeler-Nicholson was even more specific: “He should combine both brains and brawn, be able to think quickly and reason cleverly and able as well to slam bang his way out of a bar room brawl or mob attack.”

Siegel and Shuster, however, used Slam Bradley as a test run. “Superman had already been created, and we didn’t want to give away the Superman idea; but we just couldn’t resist putting into Slam Bradley some of the slam-bang stuff.”

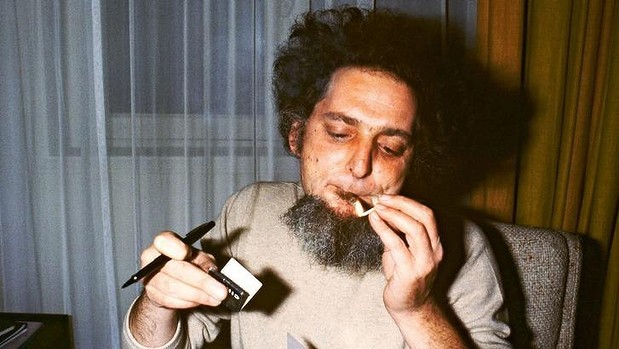

Despite his penchant for cigarettes and dames, the target audience of preteen boys took to Slam Bradley as a super hero of sorts. So Siegel and Shuster worked late nights and long hours to perfect their original character, Superman, which they felt had more appeal.

Superman made his first appearance in Action Comics in 1938.

Superman made his first appearance in Action Comics in 1938.

Even Superman’s secret alter ego, Clark Kent, was patterned after Siegel’s real life luck – or lack of it – with girls. “What if I had something special going for me, like jumping over buildings or throwing cars around or something like that, then maybe they would notice me,” he confessed.

The look of Superman changed too, from a bald headed man to the costumed, caped crusader we know today.

In an interview in 1983, Siegel compared the look of the original Superman to a popular television star at the time.

“I suppose he looks a lot like Telly Savalas,” he said.

How a Small Golf Course in Illinois Influenced the Bible’s Translation

By Ken Zurski

Palos Heights, Illinois, a small southwest suburb of Chicago, is listed in at least one version of the Holy Bible. Not in scripture, of course, but in the Preface of the New International Version, a commonly used edition today, published in 1978. It reads “…a group of scholars met at Palos Heights, Illinois, and concurred in the need for a new translation of the Bible in contemporary English.”

Amazing as that seems, the story behind the story, is just as revealing.

And it all begins with a golf course.

In 1929, a showcase 18-hole golf course opened in an unincorporated grassy area southwest of Chicago known as Navajo Fields, named, of course, for its earliest residents. The Navajo Fields Golf Course proved to be a player’s delight, including its most challenging hole number four. Although the reason why the fourth hole’s play was such a challenge is not exactly known, it certainly earned a dubious reputation at the time. Despite the toughness of the course, however, the clubhouse was decorative and cozy with several steeple ceilings and large bay windows. It served many banquets for groups who traveled out of Chicago’s fancy hotels and convention halls for a gathering in a more secluded setting.

By the early 1950’s, Navajo Fields was one of the premium golf courses in the Chicago area and each spring excited players lined up to tee off. “The prolonged coating of snow during the winter has had the effect of preserving the turf, “ course officials bragged to the Blue Island Sun Standard in 1953. “The course is in beautiful shape this year.” Even hole number four, which “plagued many golfers,” was changed. “It has been rebuilt and enlarged and the hole will have an alternate tee.”

Regrettably , the course would only last a few more years.

In 1959 the area surrounding the golf course was incorporated and renamed Palos Heights, a small suburb of Chicago with only four square miles of land and water (Lake Katherine), but today boasts nearly 5,000 mostly upscale homes in neatly designed subdivisions.

Also that year, the privately funded Trinity Christian College bought the Navajo Fields grounds, including the two buildings. The golf course was subsequently closed. The old clubhouse was remodeled and became the school’s administration building, while the pro shop became the music building. The unaccredited college opened that fall with 37 students and 5 full time faculty members.

Then in 1965, the college hosted a special meeting of religious leaders to discuss a proposal to change the Old English wording of the Bible. Specifically, to make the King James Version easier to read, more understandable and sustainable to long-term teaching. They gathered in the old clubhouse building and came up with a plan.

Here’s why: In 1952, a Revised Standard Version of the Bible was released by the National Council of Churches, the ecumenical body of mainline Protestant denominations in the United States. Opponents of the new version, mostly hardliner Protestant conservatives, more commonly known as Evangelicals, refused to adopt it, sticking with the original King James version for scripture readings instead.

Here’s why: In 1952, a Revised Standard Version of the Bible was released by the National Council of Churches, the ecumenical body of mainline Protestant denominations in the United States. Opponents of the new version, mostly hardliner Protestant conservatives, more commonly known as Evangelicals, refused to adopt it, sticking with the original King James version for scripture readings instead.

Change was needed.

So the Evangelical council along with the Christian Reformed Church, a group founded by Dutch immigrants, who were also looking for a more streamlined and Americanized version of the Bible, came to Palos Heights.

Why they chose Trinity Christian College is curious, but understandable. It was discreet and private, yes, but also represented the type of educational institution a translated bible would benefit the most. Plus, if it didn’t go as planned, no one would know. Not much was publicized while the work commenced. A New York group would fund the project.

This reticent attitude is likely due to the monumental challenge and possible backlash for such an undertaking. The Revised Standard Version was widely considered to be the first time the King James version had been extensively tinkered with since the early 17th century.

But that was not entirely true.

In the early 19th century, Noah Webster, yes, the dictionary guru, also wanted to change the King James Version of the Holy Bible. He had a different agenda, however. He hated what the majesty’s version stood for. Not the religious aspect, that was fine, but it was too British, too overbearing, offensive and insulting. So Webster set out to make it more American, and the language, more like Americans speak. This is what Americans wanted, he thought.

He was wrong. While his intentions were noble enough, the King James Version even after the end of British rule, continued to be accepted in America. Webster refused to back down. He went to work changing words he didn’t like and fixing grammar problems he called “atrocious.”

Webster’s “Holy Bible … with Amendments of the Language” or “Common Version” appeared in 1833. It was a colossal failure. A big, wordy waste of time, many thought. So dismissed, that a year later in 1834, Webster put out another book, an apology of sorts, but defending the Bible’s message and Christianity as a whole. Even at the age of seventy, he emphasized the importance of its completion. “I consider this emendation of the common version as the most important enterprise of my life,” he said.

Webster was off by nearly a hundred years.

By the mid 20th century, large church denominations were opening privately funded colleges and teaching the word of the Bible to students in hopes of sparking a revolution in religious educators and young pastors. The King James version of the Bible needed a revision. The Revised Standard Edition was a start. But the Evangelicals thought they could do better. So in Palos Heights, they came up with imperatives. For one, they needed more denominations to join in. They also needed a slew of scholars from around the world to participate. This unity -and variety – would safeguard it from sectarian bias, they thought, something the Revised Standard Edition did not do. Soon enough they assembled a team of scholars from a group of churches: Anglican, Assemblies of God, Baptist, Brethren, Church of Christ, Evangelical Free, Lutheran, Mennonite, Methodist, Nazarene, Presbyterian, Wesleyan, among others. The next year, at the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, they put their plan to work.

According to the Preface of the New International Version, the detailed process went like this:

The translation of each book was assigned to a group of scholars. Next, one of the Intermediate Editorial Committees revised the initial translation, with constant reference to the Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek. Their work then went to one of the General Editorial Committees, which checked it in detail and made another thorough revision. This revision in turn was carefully reviewed by the Committee on Bible Translation, which made further changes and then released the final version for publication.

Among the many changes, old verbs like “doest,” “wouldest” and “hadst” were tossed out and replaced. Pronouns like “Thou” and “Thine” – referring to the Deity – were also considered too archaic. “If there was uncertainty about such material, it is enclosed in brackets,” explained the Committee on Bible Translation. “Also for the sake of clarity or style, nouns, including some proper nouns, are sometimes substituted for pronouns, and vice-versa.”

Among the more interesting added features were the italicized sectional headings. This is the one part of the new work that was wholly generated by present day writers. They are simple chapter titles designed to give the reader quick reference in themes. For example, in the Book of John some of the headings include, Jesus Walks on Water and The Plot to Kill Jesus.

It took nearly 10 years and several revisions before the New International Version was published in 1978 and although slight additions and subtractions would come later, the original vision remains the same. “The most massive and painstaking literary tour de force in history,” one newspaper writer enthused upon its initial release.

It took nearly 10 years and several revisions before the New International Version was published in 1978 and although slight additions and subtractions would come later, the original vision remains the same. “The most massive and painstaking literary tour de force in history,” one newspaper writer enthused upon its initial release.

Dr . Burton L Goddard, a theologian who worked on the new Bible was grateful, but relieved. “We all acknowledge this to be the hardest work we have ever known,” he expressed.

Trinity Christian College still sits on the grounds of the old golf course in Palos Heights. In 1966, the board initiated the process for the college to become a four-year, degree-granting institution. The first baccalaureate degrees were awarded in May 1971. More buildings were added but many were built similar in style to original clubhouse. Today it’s still considered a small school by college standards, with just over 1500 in enrollment.

In 1983, during a new printing of the New International Version a line was added to the Preface to reflect a very Christian-like humble attitude: “Like all translations of the Bible, made as they are by imperfect man, this one undoubtedly falls short of its goals.”

Oh, the anxieties of high expectations.

Kind of like playing golf.

How William H. McMasters Exposed Ponzi’s Scheme

By Ken Zurski

William H. McMasters was all ears.

In 1920, when an Italian immigrant and dreamer named Charles Ponzi walked into the Boston publicist’s office to promote his business, McMasters listened.

Ponzi was using investments to buy postal coupons internationally and reselling them for profit in the U.S. It was totally legal and ingenious.

Ponzi needed to recruit more investors and McMasters was just the person to do it. “I was not averse to having a millionaire as a client,” McMasters later remarked.

McMasters immediately set up an interview at The Boston Post, which was an instant boon for Ponzi. Everyone wanted in. Everyone that is, except McMasters.

The numbers didn’t add up.

Ponzi was recruiting new investors, but far too many. The amount of postal coupons was limited so the promised return was higher than the take. Ponzi knew this, but didn’t tell. McMasters went back to the Post.

Ponzi was recruiting new investors, but far too many. The amount of postal coupons was limited so the promised return was higher than the take. Ponzi knew this, but didn’t tell. McMasters went back to the Post.

The editors were interested in exposing Ponzi, but leery of the process. They didn’t want to get sued. So McMasters wrote an article titled “Declares Ponzi is Now Hopelessly Insolvent.” In it, he explained that Ponzi had invested none of his own money or personally bought any of the stamps.

He used investor money to pay returns, but didn’t know when to stop. Now there were too many investors, too much money owed, and not enough printed stamps to guarantee payouts.

On August 2nd , The Post ran the article and prominently displayed it on the front page.

The next day, the Ponzi scheme was over.

In the end, McMasters found only complacency in his role. While most investors angrily demanded their money back, there were a select few for whom Ponzi’s charm was too persuasive.

They still thought they were getting rich.

Eventually, they blamed McMasters, not Ponzi, for their predicament.

Lar Daly and the Art of Losing Elections

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

In 1952, the name General MacArthur appeared on the Wisconsin Republican primary ballot for President of the United States. This was unusual, because the famous general everyone knew, Douglas MacArthur, was not in the running.

More on that in a moment.

First, the person responsible for the inclusion of General MacArthur on the ballot is a man named Lawrence Joseph Sarsfield Daly, or Lar Daly for short. Daly was a political shill from the Midwest who unsuccessfully ran for a variety of political offices including Mayor of Chicago and eventually President of the United States. “What made [Daly] famous was his hobby,” a Chicago historian once wrote. “He ran for public office –and lost.” In 1952, however, Daly had another tapped for the White House, Douglas MacArthur, the popular World War II general.

That year President Harry Truman decided he would not seek reelection for a second full term and backed Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson II for the nomination instead. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the clear choice on the Republican side. Daly, however, liked another general, MacArthur, who had made it clear from the onset that he was not in the running. Daly, who had just lost to Representative Everett Dirksen of Pekin in the 1950 Republican primary election for the Illinois U.S. Senate seat, took the matter in his own hands. Without permission, he added the general’s name to the list of Republican nominees in the Illinois primary.

When MacArthur found out, he promptly had it removed.

Undeterred, Daly tried a different tactic in the Wisconsin primary. He grabbed the Chicago phone book and looked up the name MacArthur. To his surprise he found a man with the last name MacArthur and first name, General.

Daly called the man and asked if he knew of the famous general. The man said he thought the general was a “fine American.” When Daly asked if he could put his name on the ballot, General MacArthur, a 42-year old African American with eight children, said “yes.”

By law, as long as there was a signed consent, the name Mr. General MacArthur could legally appear on the Wisconsin ballot.

The novelty, however, was never a secret. Thanks to Daly, Mr. MacArthur took a few smiling photos for “Life” magazine and other publications, but never sought out any publicity for himself or his family. There were no monetary awards for his efforts. He continued to work as a tank inspector at a packinghouse. Nothing changed.

Daly hoped to find some delegates in the state and perhaps drum up support for Gen. Douglas MacArthur to consider a run, but there were few takers. Eisenhower easily won the nomination and later that year beat Stevenson by a landslide for the presidency.

Privately, Daly lived in a modest two story brick bungalow on Chicago’s south side and drove a Ford Station wagon, painted red, white and blue. He had six children and sold bar stools for a living. “To bookies,” he once said, “so they had somewhere to stand when they wrote the odds on the chalkboard.”

Born in Gary, Indiana in 1912, Daly’s mother died when he was five. His father, a policeman and fireman in town, moved the two boys, Lar and his brother, to Chicago. That’s where Lar became politically connected. In the second grade, he sold vegetables for a street peddler and gained friends among the local housewives. This would work to his advantage. As a teenager, Lar worked the streets again. No longer was he peddling produce, but candidates. He passed out fliers and helped vote seekers gain support in his Chicago neighborhood. At the age of 20, Daly decided to run against a powerful Cook County Democratic ward committeeman. He lost big in the election but won by defeating a court challenge of filing fake petition signatures. “I knew my petitions are good,” Lar said in his defense. “I got all the signatures myself.” Just getting on the ballot was a victory of sorts for the young politico.

In 1938, Lar ran for Cook County Superintendent of Schools, even though he himself never got past the first year of high school. He was listed as Lawrence J. Daly on the ballot and thanks to the Irish sounding name picked up nearly 300,000 votes, but still lost. It would remain the closest he ever came to actually winning an election.

Politically, Daly was an equal-opportunity candidate and ran on whichever ticket gave him the best shot to win. His views, however, were more in line with libertarians. He was for legalized gambling, against public education, and called for major tax cuts. He was also a staunch isolationist, often making campaign stops wearing an Uncle Sam suit, and calling himself the “America First” candidate.

In 1960, he was a “write in” candidate for President.

Even though he was never considered a serious threat to the two major parties, Daly sued – some say threatened – the FCC to force radio and television news broadcasts to give him equal coverage. He never got on the debate stage with the two nominees, then Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice-President Richard M. Nixon, but when JFK guested on The Tonight Show, Jack Paar’s late-night NBC talk show, Daly demanded—and got—his “equal time.” Paar was furious but went along. “Mr. Daly, I would like to know where your supporters are located” challenged a man in the audience. “I teach special studies in Illinois, and we’ve never heard of you.”

“Well, sir,” replied Daly, “you apparently don’t read newspapers, watch television, listen to the radio, or attend meetings, because in every Illinois campaign in which I engage, I am known as the tireless candidate.”

The studio audience booed as Daly calmly demanded: “Your only choice is America first—or death.”

Parr cut to a commercial, “for the tireless candidate,” he said sarcastically.

After the taping, Lar took off his Uncle Sam suit went to a New York bar and inconspicuously watched the show as it aired that night. “Holy smokes, what the hell is this?” said a patron during Daly’s segment.

Daly hardly registered a vote in the 1960 general election, besides his own. But that didn’t stop him. He continued on each subsequent year for many more years, running for offices mostly in Illinois for the U.S Senate seat and numerous attempts for Mayor of Chicago against another Daley (spelled differently).

He lost, of course, every time.