unrememebred history

In 1965, The Detergents Had That One ‘Dirty’ Song

By Ken Zurski

In early 1965, a three-member American band named The Detergents released a single titled “Leader of the Laundromat.”

In early 1965, a three-member American band named The Detergents released a single titled “Leader of the Laundromat.”

The song told the story of a boy named Murray who was seemingly in love with a pretty laundromat attendant, Betty, because she “looked so sad.”

Then he abruptly tells her it’s over between them.

I’ll never forget the hurt and the funny look in her eye.

Betty, the jilted ex-girlfriend, grabs Murray’s laundry, runs out the laundromat door, and “directly in the path of a garbage truck.”

Watch out, watch out!

Those familiar with a certain Shangri-La’s song “Leader of the Pack,” of which whose melody The Detergent’s mimicked, might have been shocked out of their shoes.

But it was all in good fun.

I felt so messy standing there

My daddy’s shorts were everywhere

Tenderly I kissed her goodbye

Picked up my clothes, they were finally dry

The song was a parody, of course, but more specifically, it was a spoof. Until then, parody songs had been about something funny and usually with an original melody like “Itsy Bitsy Tennie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini.” But the “Laundromat” song was different. It took the actual melody of a recent hit and twisted it. Basically, it spoofed an already established and popular tune.

But I won’t forget you, oh Leader Of the Laundromat

That didn’t sit so well with the writers of the original song. When the “Leader of the Laundromat,” reached #19 on the Billboard singles chart, the songwriting team behind “Leader of the Pack” sued The Detergents for copyright infringement and royalties and settled out of court.

Despite the legal wrangling, however, band members Ron Dante, Danny Jordan and Tommy Wynn, toured together as The Detergents for about two years before disbanding.

Dante went on to sing lead vocals for the novelty group The Archies and the hit single “Sugar, Sugar,” a contribution that was unacknowledged at the time thanks to the group’s association with the comic strip characters.

The Detergents short legacy includes an album of spoofs, a film (like the Beatles), and some subsequent singles, like “Double-O-Seven” (A James Bond mockery) and “I Can Never Eat at Home Anymore” (inspired by another Shangri-Las hit “I Can Never Go Home Anymore”), but nothing stuck quite like the “Laundromat” song:

My folks were always putting her down (down, down)

Because her laundry came back brown (brown, brown)

(Lyrics reprinted from Google Play Music)

One of the First Rotary-Wing Pilots is Someone You Already Know

By Ken Zurski

On April 8 1931 at Pitcairn Field in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, the most famous woman pilot in the world stepped into an autogiro, a horizontally propelled winged aircraft she had been testing with other pioneer aviators for more than a year.

Her name, of course, was Amelia Earhart, who in 1928, had become the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. Now several years later, a large appreciate crowd was on hand to see her attempt another record. This time an altitude peak in the mostly untested autogiro, a prototype for the modern day helicopter.

She would not disappoint.

Introduced in the 1930’s, the autogiros was considered a more practical and efficient alternative to the airplane. It was also unstable and unproven. There were, however, striking differences in flight. Autigiros could take off from a relatively small space and fly just as high and as long as its front-propelled counterpart. But unlike the airplane, it could also stop on a dime and seem to float in the sky. Landing was simply lowering itself to the ground. The blade on top was free spinning and powered by air from an engine-propelled rotor on the side that also provided thrust.

Today, a smaller version, called a gyrocopter, is similar to the original design without the wings. So when you talk about the pioneer fliers of the autogiro, or the forerunner of the helicopter, one person must be recognized.

One you famously know.

The aforementioned Amelia Earhart.

So in 1931, with a large contingent of press on site, Earhart in her thick insulated overalls gave it a go. Her first attempt failed. Perhaps as some noted, she was testing her own capabilities. Maybe she would abandon the next attempt, the press speculated. She answered that question by going up again, this time reaching a height of 18,415 feet and breaking – or making –a new record. She safely brought the craft back to the ground.

She was lauded in her efforts, but wanted more. So did the press. They figured she would try a transcontinental trip in an autogiro, the first of its kind, which she did successfully. But her efforts were overshadowed by another pilot named John Miller who quietly attempted the same feat without the fanfare or publicity that Earhart demanded. He completed the route first, although both pilots had no idea of the other’s intentions.

That same year in 1931, Earhart crashed her autogiro at an airshow in Detroit. Her husband, George Putnam, was the first to arrive at the wreckage: “I saw Amelia emerge from the dust and wave her hands in the air,” he said. “She was unhurt.” But Putnam was on the ground, writhing in pain. In his haste to reach the wreck site he tripped, fell and cracked three ribs. “Never had I run so fast,” he described afterwards, “until one of the guy wires caught my pumping legs exactly at the ankles.”

Unaware of her husband’s injury, Earhart happily acknowledged to the crowd.

While she was glad to walk away unscathed and Putman’s predicament was just an unfortunate accident, it would be her last call with the autogiro.

She went back to an aircraft with wings and a propeller in the front.

Tragically, six years later in 1937, over the Pacific, her legacy as it is known today would begin.

The Origins of Father’s Day: A ‘Second Christmas’ for Dads

By Ken Zurski

Nearly every May in the 1930’s, a radio performer named Robert Spere staged rallies in New York City promoting a day set aside not just to honor moms, but dads as well.

His hope was to change “Mother’s Day” to “Parent’s Day” instead.

Spere, a children’s program host known as “Uncle Robert” told his attentive audience: “We should all have love for mom and dad every day, but ‘Parent’s Day’ is a reminder that both parents should be loved and respected together.”

Spere was onto to something, but it would have to wait.

Much earlier, in 1908, a day set aside to celebrate mom, affectionately known as Mother’s Day, became a national day of observance. But there was no enthusiasm for a day set aside for fathers. “Men scoffed at the holiday’s sentimental attempts to domesticate manliness with flowers and gift-giving,” one historian wrote.

Retailers, however, liked the idea. They promoted a “second Christmas” for dads with gifts of tools, neckties and tobacco, instead of flowers and cards. But it never gelled. Even Spere’s “Parent’s Day” idea hit a snag when the Great Depression hit. (Today, “Parents Day” is officially celebrated on the fourth Sunday of every July.)

In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed a proclamation honoring fathers on the third Sunday of June.

Six years later, in 1972, with President Richard Nixon’s signature, “Father’s Day” officially became a national holiday.

Baseball’s ‘Pastimes’ Played the Game For Fun Only

By Ken Zurski

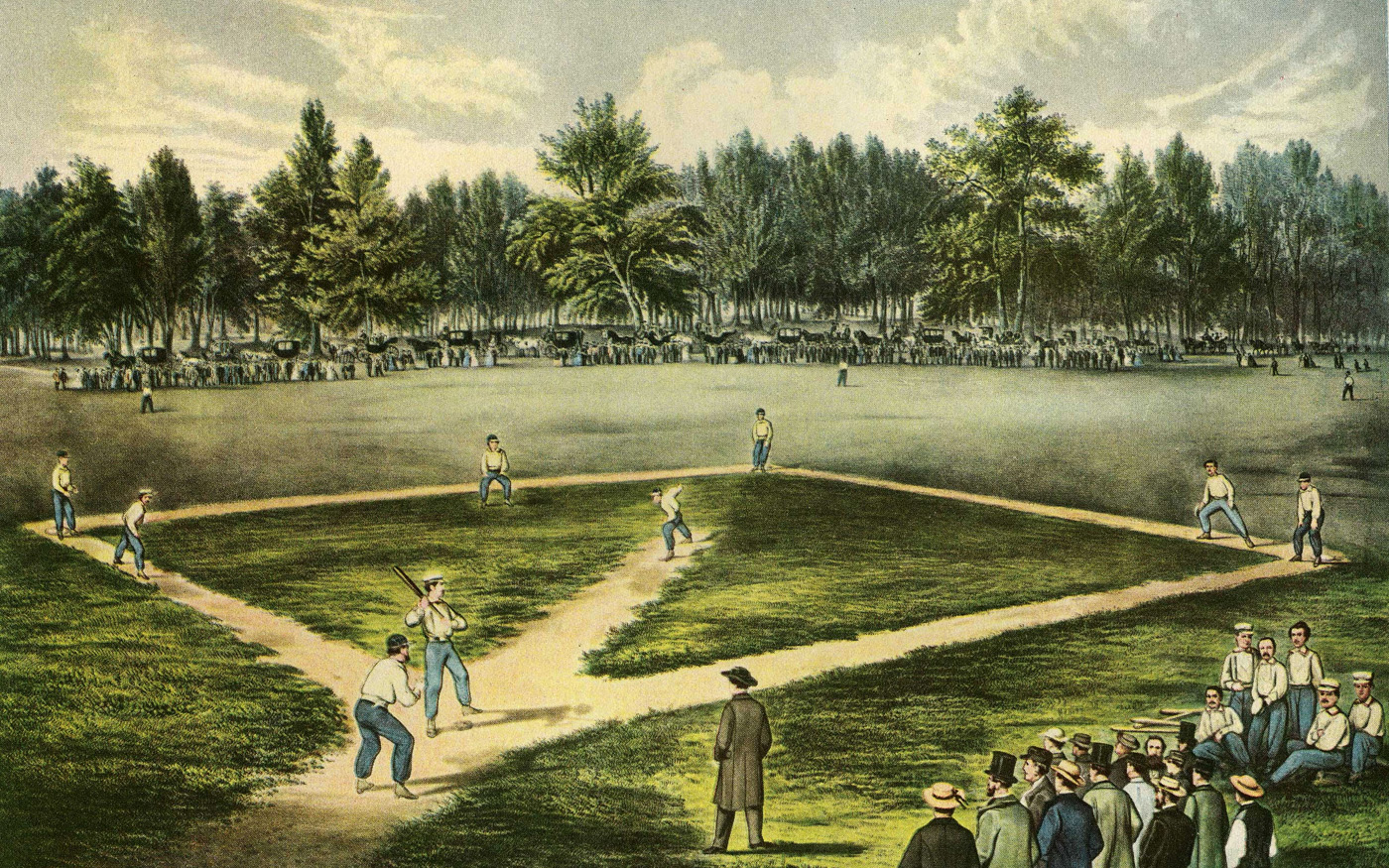

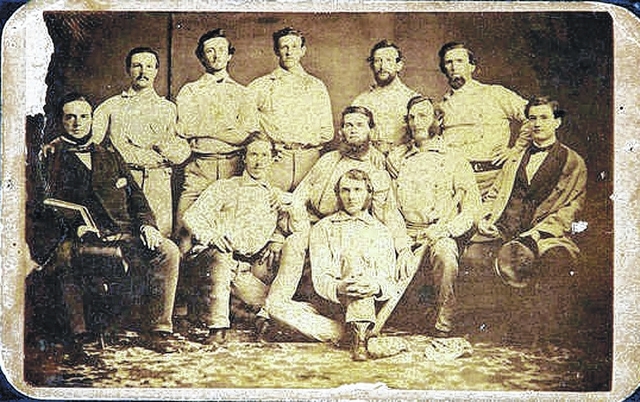

In the heart of Brooklyn, in 1858, a group of men known as the Pastimes, hiked up their wool trousers, buttoned-down their flannel shirts, and ran onto an open grassy field to play a game they fondly referred to as “base ball.”

The team was one of several in the New York area, but the Pastimes were different. Instead of being a ragtag lot of patchwork players, the Pastimes billed themselves as more refined and high-minded. Many of the members were prominent citizens, some even held government jobs. They enjoyed spending the day together, socializing and being seen.

Base ball, the game, they said, was just good exercise.

To signify their self-worth, the Pastimes arrived at away games in carriages and usually in a line. “Like a funeral procession passing,” remarked one observer. You couldn’t help but notice.

After the game they invited their rivals, win or lose, to a fancy spread of food and spirits. Oftentimes this was the reason for getting together in the first place. The game was the appetizer. The day’s highlight however was the feast. The opposing players rarely complained.

Despite the revelry off the field, the Pastimes did actually play the game. But it hardly represented what we know baseball to be today. Pitchers tossed the ball (there was no “throwing” allowed) and strikes were rare. With no called balls, a batter could wait through 30 to 40 tosses or more before deciding to hit it. The batter was out when a fielder caught the ball on a fly or on “a bound.” And player’s running the bases rarely touched them. After all, who was going to make them? “What jolly fellows they were at the time,” wrote Henry Chadwick, a New York journalist and Pastimes supporter, “one and all of them.”

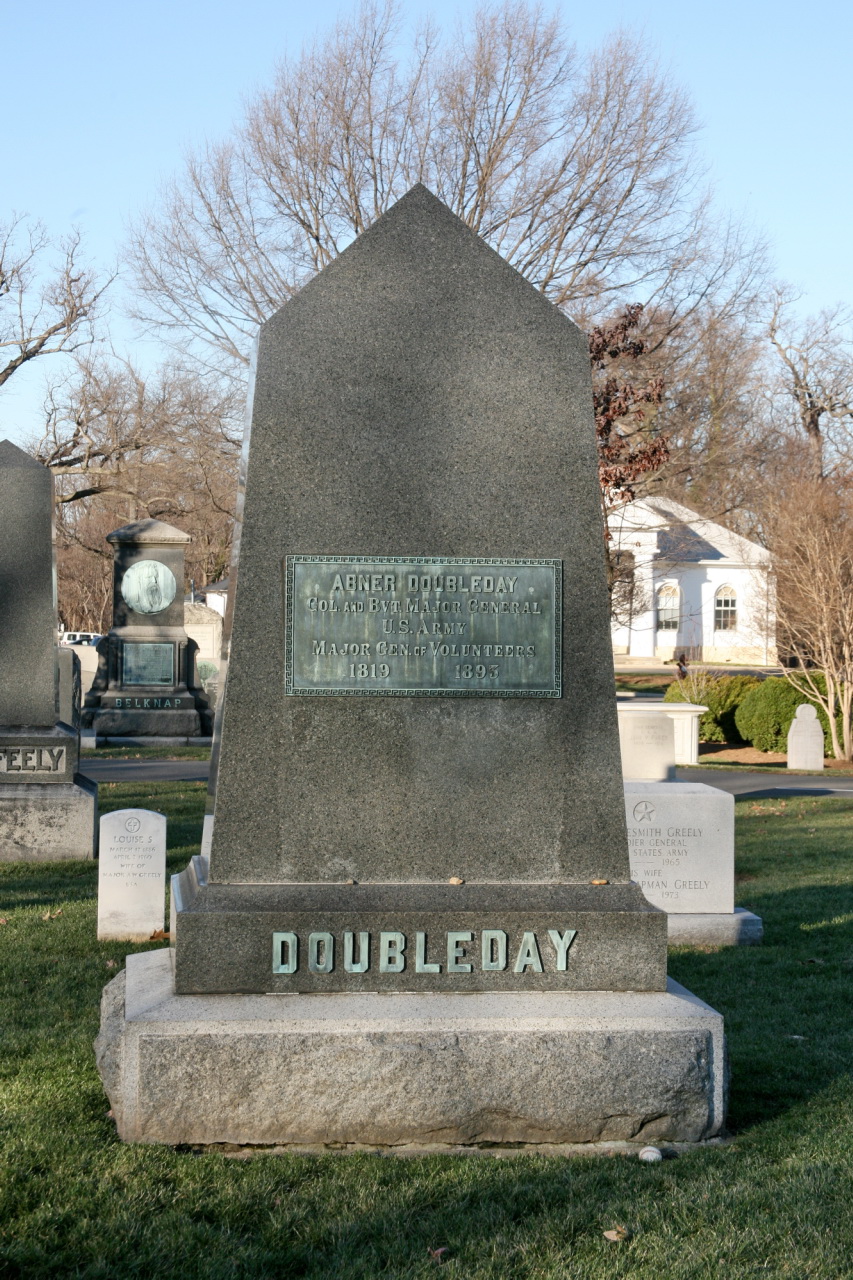

Most of the early history of baseball hails from New York, with Cooperstown, considered to be the place where the game was invented and the current site of the Baseball Hall Of Fame and Museum, as a prime example. While bat-and-ball type games were popping up throughout the country, in New York, an actual team emerged in the 1840’s calling themselves the Knickerbockers. While they’re not trailblazers in creating the game, they can be considered pioneers when it comes to the sport. The Knickerbockers actually made and followed some rules.

The play itself was raw, almost comical, but enjoyable for spectators. “Ball Days” became popular, and the Knickerbockers were fun to watch. Soon other teams would join in, some more determined than others. The Pastimes had their reasons too.

At some point, as more teams participated, the game started changing. It became more challenging and competitive and the Pastimes who had been enjoying a day of friendly raillery – and not much more – had to adjust. “Until the club became ambitious of winning matches and began to sacrifice the original objects of the organization to the desire to strengthen their nine-match playing,” Chadwick wrote, “everything went on swimmingly.” But losing takes its toll. And for the lowly playing Pastimes, the fun went out of the day. “Finally the spirit of the club, having been dampened by repeated defeats at the hands of stronger nines, gave out,” Chadwick grumbled on. “The Pastimes went out of existence.”

Well that and the start of the war too.

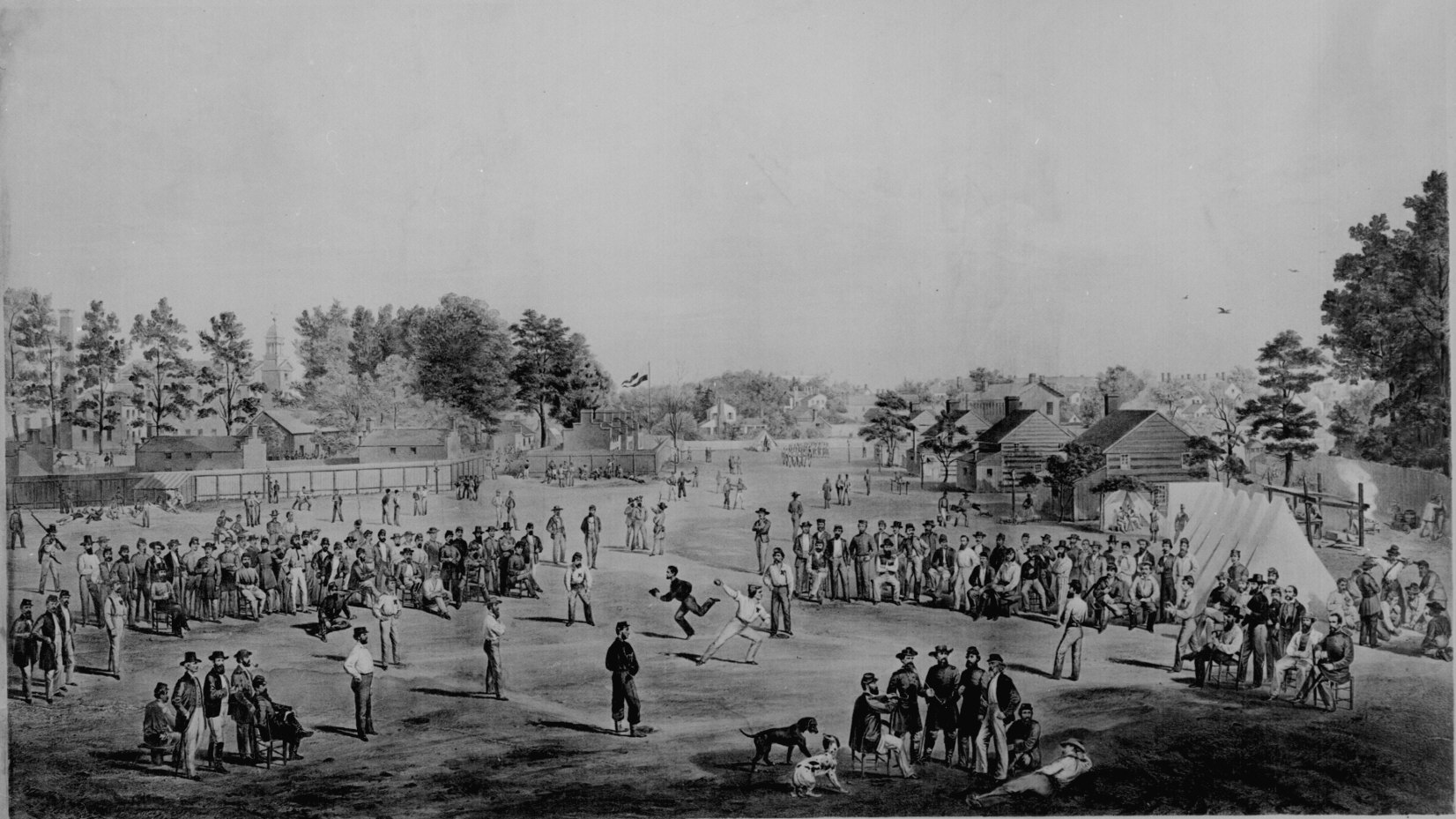

Conventional wisdom would suggest that the Civil War slowed the progress of the game. And that was true, to a point. Inevitably as men marched off to war, there just weren’t enough players to take the field. Many top players did heed the call to serve, but others chose to delay their service and keep playing. Plus there were always reserves, especially in a well populated state like New York. The game carried on, despite the conflict. In fact, it was just as popular for the soldiers who shared a good game of nines to help pass the time. “Each regiment had its share of disease and desertion; each had it’s ball-players turned soldiers,” remembered George T Stevens, of the 77th Regiment, New York Volunteers. Baseball was a game that required an open space, a stick, something to hit, and not much else. Reports of ball games in prison camps were widespread.

Once the conflict was over, the game itself was in for an overhaul. Many of the older players were either injured, weary from the war, or worse. That’s when younger players joined in, skills improved, and rules were implemented.

Base ball became Baseball – a legitimate competitive sport.

The Pastimes would have never fit in.

Perhaps the most appealing part of the early game would have also pleased the more ardent followers of baseball today, especially those who crave the action on the offensive side of the ball. On October 28, 1858, the Pastimes played the Newark Adriatics. According to the rules back then, a game played out every half inning, even in the ninth, and even if the home team was winning.

That day, the Adriatics came to bat in the bottom of the ninth. They were leading 45-13.

The crowd likely cheered them on for more runs.

Walt Disney, the Early Shorts, and ‘Oswald the Lucky Rabbit’

By Ken Zurski

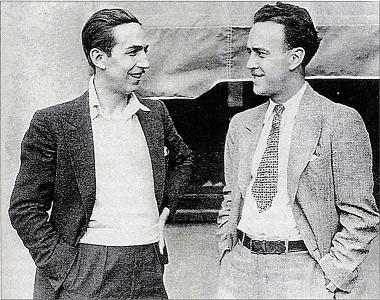

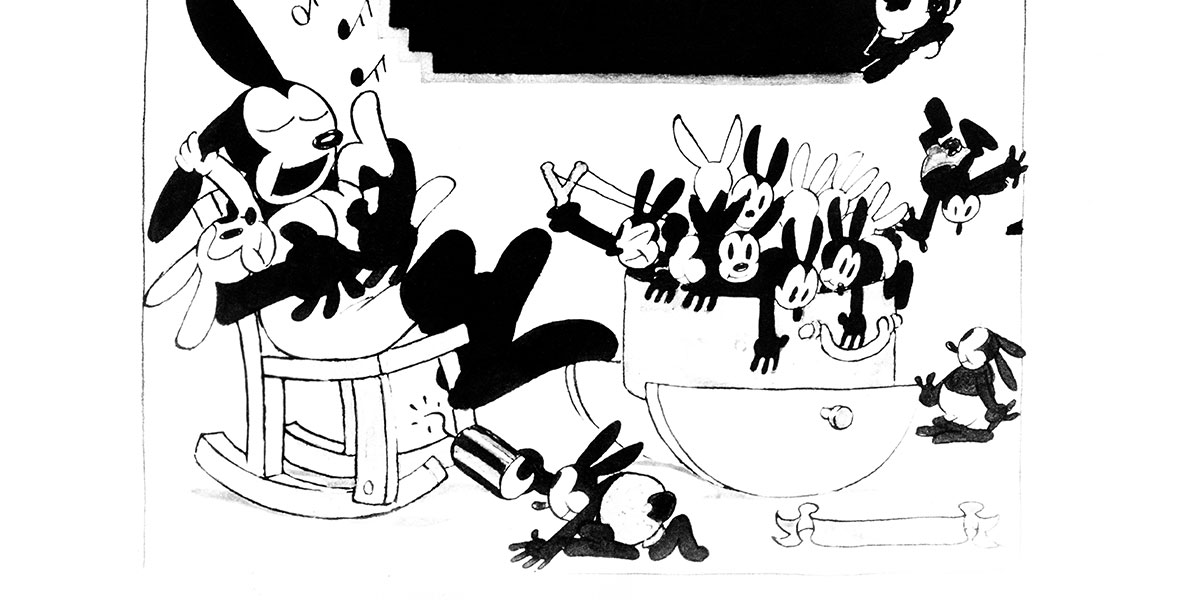

His face was round, his body rubbery. He laughed. He cried. For kicks, he could take off his long supple ears and put them back on again. His name was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and he was the first major animated character created by a man who would later become – and still is – one of the most enduring public figures of our time: Walt Disney.

Walter Elias Disney was just in his twenties when the idea for Oswald came along. A gifted graphic artist from the Midwest, Disney had spent some time overseas during World War I as an ambulance driver and returned to the U.S. to work for a commercial arts company in Kansas City, Missouri. Disney had a knack for business. He partnered with a local artist named Ub Iwerks and together they formed their own company, Iwerks –Disney (switching the name from their first choice of Disney- Iwerks because it sounded too much like a doctor’s office: “eye works”).

They dabbled in animation and soon were making shorts, basically live action films mixed with animated characters. They made a slew of little comedies called Lafflets under the name Laugh-O-Grams. It was a tough sell. Studios backed out of contracts and various offers fell flat.

Disney never gave up and soon they had a series called Alice the Peacemaker based loosely on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Alice was different and seemingly better. They used a new technique of animation, more fluid with fewer cuts and longer stretches of action. Alice, the heroine of the series, was a live person, but the star of the comedies was an animated cat named Julius. The distributor of the Alice shorts, an influential woman named Margret Winkler, had suggested the idea. “Use a cat wherever possible,” she told Disney, “and don’t be afraid to let him do ridiculous things.” Disney and Iwerks let the antics fly, mostly through their feline co-star.

When Alice ran its course and Disney was thinking of another series and character, he wanted it to be an animal. But not a cat, he thought, there were already too many. That’s when a rabbit came to mind. A rabbit he named Oswald.

It was a shaky start. The first Oswald short, Poor Papa, was controversial even by today’s standards. In it, Oswald is overwhelmed by an army – or air force, if you will – of storks each carrying a baby bunny and dropping the poor infants one right after the other upon Oswald’s home. Oswald was after all a rabbit and, well, rabbits have a reputation for being prodigious procreators. But this onslaught of newborns, hundreds it seemed, was just too much for the budding new father. Oswald’s frustration turns to anger and soon he brandishes a shotgun and starts shooting the babies, one by one, out of the sky like an arcade game. The storks in turn fire back using the babies as weapons.

Pretty heady stuff even for the 1920’s, but it wasn’t the subject matter that bothered the head of Winkler productions, a man named Charles Mintz. It was the clunky animation, repetition of action, no storyline, and a lack of character development that drew his ire.

Disney and Iwerks went back to work and undertook changes that made Oswald more likable – and funnier. They made more shorts and audiences began to respond. Oswald the Lucky Rabbit caught on. Soon, Oswald’s likeness was appearing on candy bars and other novelties.

Disney finally had a hit. But the reality of success was met with sudden disappointment. Walt had signed only a one-year contract, now under the Universal banner, and run by Winkler’s former head Mintz. The contract was up and Mintz played hardball. He wanted to change or move animators to Universal and put the artistic side completely in the hands of the studio. Walt was asked to join up, but refused. He still wanted full control. Seeing an inevitable shift, many of Disney’s loyal animators jumped ship, but Walt’s close friend and partner Ub Iwerks stayed on. Oswald was gone, but the prospects of a new company run exclusively by Walt were at hand.

Under Universal’s rule, Oswald’s popularity waned. Mintz eventually gave the series to cartoonist Walter Lantz who later found success in another popular character, a bird, named Woody Woodpecker. Oswald dragged on for years, as cartoons often do, and was eventually dropped.

Disney, meanwhile, needed a new star.

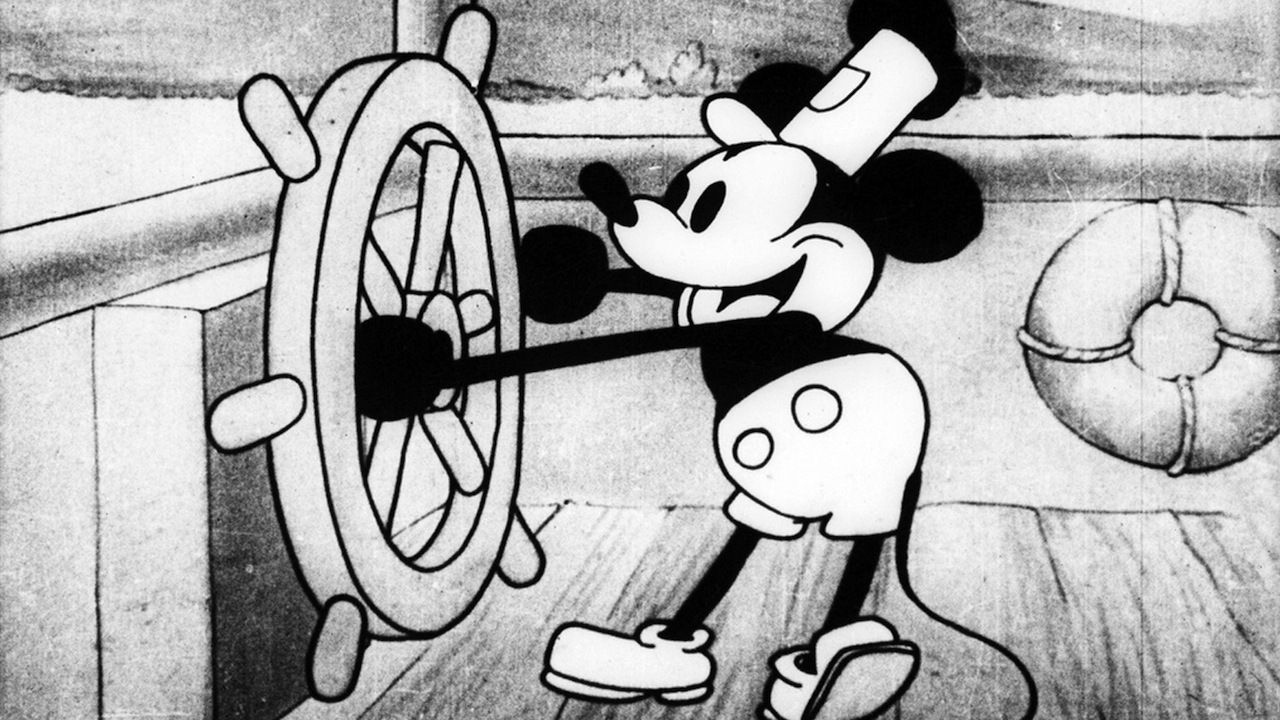

Here’s where it gets better for Walt. In early 1928, Disney was attending meetings in New York when he got word that his contract with Universal would not be renewed. Although he later said it didn’t bother him, a friend described his mood as that of “a raging lion.” Disney soon boarded a train and steamed back west. As the story goes, during the long trip, Disney got out a sketch pad and pencil. He started thinking about a tiny mouse he had once befriended at his old office in Kansas City. He had an idea. He began to draw a character that looked a lot like Oswald only with shorter rounded ears and a long thin tail.

Steamboat Willie starring Mickey Mouse debuted later that year.

George Custer’s Reluctant Ride in a War Balloon

By Ken Zurski

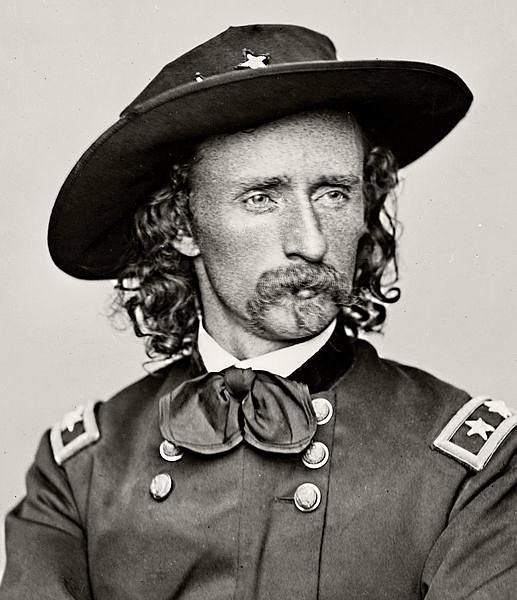

In 1862, at the age of twenty-two, and nearly 15 years before his death at the Battle of Little Bighorn, the newly appointed Captain George Armstrong Custer went up in a hydrogen-filled balloon over the Virginia Peninsula, not far from Richmond, the rebel capitol.

A short and uneventful ride in a balloon is not the stuff of legends and this brief episode in Custer’s life is understandably unremembered. We know it happened only because Custer chose to write about it. And only because he chose to write about it, do we know he didn’t care for the experience as a whole.

So much for balloons in the Federal Army, right?

Not so. Abraham Lincoln certainly recognized the need. By the time Custer went up, tethered balloons were being used – albeit sparingly – for surveillance in the Civil War. A man named Thaddeus Lowe is the reason why. In April of 1861, Lowe flew one of his balloons over Unionville in the newly seceded state of South Carolina. He landed and was subsequently captured as a Union spy. Lowe claimed he was “a man of science” and let go. Despite this rather dubious start, Lincoln invited him to Washington to test the use of a telegraph wire tied to the balloon’s tether. Lowe’s first dispatch was sent directly to a service room in the White House. “This point of observation commands an area nearly fifty feet in diameter,” Lowe messaged. Lincoln immediately directed Lowe to form a Balloon Corps, more formally known as the Military Aeronautics Corps.

Lowe was given funds to make more balloons and soon enough there were eight in all with distinctly patriotic names: Union, Intrepid, Constitution, United States, Washington, and the Eagle. The first balloon used for official military purposes, the Union, ascended on September 1861 near Arlington, Virginia. From a vantage point nearly three miles away, Confederate troops were spotted in Falls Church. Instantly, telegraph intelligence improved.

But when the battles slowed, Lowe had little to do and turned to promoting his balloon business instead. He got into the habit of allowing journalists to take rides. Most of them were eager to do so because it made good copy. However, many of the enlisted men and officers, were not so easily influenced. Perhaps this was out of caution- or fear. After all one unfortunate officer named Fitzjohn Porter, a lieutenant-general, almost never made it back alive.

Porter was in a balloon that broke from its tether and flew into rebel territory, near Yorktown. The balloon drifted directly over enemy outworks and sharp shooters aim, but whether Porter was actually fired upon is unknown. Luckily he caught an “air-box,” drifted back into camp and landed onto some Union tents, not far from where he launched. Porter was fine, but his nerves were shot.

This mishap must have been in Custer’s mind when he agreed to go up in one of Lowe’s balloons. “My desire, if frankly expressed, would not have been to go up at all,” he wrote, never disclosing why he changed his mind. “If I was to go,” he continued, “company would certainly be desirable.”

Custer’s balloon mate was one of Lowe’s assistants, James Allen. “[Mr. Allen] began jumping up and down testing it’s strength,” Custer related. “My fears were redoubled. I expected to see the bottom of the basket give way, and one or both of us dashed to the earth.”

Custer wasn’t taking any chances. He sat crouched in the basket for most of the trip. “I was urged to stand up,” he wrote, and at some point did. What he witnessed impressed him. “To the right could be seen the York River, following which the eye could rest on Chesapeake Bay. On the left, and about at the same distance, flowed the James River.”

With his field glasses, Custer spotted the enemy camp. “Men in considerable numbers were standing around entrenchments…intently observing [our] balloon, curious, no doubt, to know the character or value of the information it occupants could derive from [our] elevated post of observation.” Still his attitude toward balloons was skeptical at best. “To me it seemed fragile indeed.”

Custer’s balloon ride was in April of 1862. By the end of May, Commanding General George B. McClellan had heard enough. The balloons were too important a resource to be used for entertainment. He banned all joy rides and required Union officers to have written permission from him personally before going up.

The balloons would be used for surveillance purposes only.

Although he was a bit reckless and already had a reputation for doing things his own way, thanks to this one balloon ride, Custer gladly accepted the general’s orders.

(Sources: Falling Upwards: How We Took To The Air by Richard Holmes; various internet sites)

The Golden Gate Bridge, Willie Mays, and the Inspiration For ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’

By Ken Zurski

In 1965, while traveling by taxi over the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, television producer Lee Mendelson heard a single version of “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” a Grammy Award winning jazz song written and composed by a local musician named Vince Guaraldi.

Mendelson liked what he heard and contacted the jazz columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Can you put me in touch with Guaraldi? he asked.

Mendelson was a producer at KPIX, the CBS affiliate in San Francisco at the time and had just produced a successful documentary on Giants outfielder Willie Mays. “For some reason it popped into my mind that we had done the world’s greatest baseball player and we should now do a documentary on the world’s worst player, Charlie Brown” Mendelson explained.

“I called Charles Schulz, and he had seen the [Willie Mays] show and liked it.” Mendelson’s mind raced with ideas. That’s when he took a taxi over the idyllic Golden Gate Bridge and was inspired by the music on the radio. Why not score the documentary with jazz music? he thought.

Mendelson called Guaraldi, introduced himself, and asked him if he was interested in scoring a TV special. Guaraldi told him he would give it a go. Several weeks later, Mendelson received a call. It was Guaraldi. I want you to hear something, the composer explained , and performed a version of “Linus and Lucy” over the phone.

Mendelson liked what he heard.

But the documentary never aired. “There was no place for it,” Mendelson said. “We couldn’t sell it to anybody.” Two years later soft drink giant Coca Cola contacted Mendelson and inquired about sponsoring a “Peanuts” Christmas special. “I called Mr. Schulz and I said ‘I think I just sold A Charlie Brown Christmas,’ and he said ‘What’s that?’ and I said, ‘Something you’re gonna write tomorrow.”

Mendelson decided to use Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy,” which had already been composed for the documentary. “The show just evolved from those original notes,” Mendelson described.

The rest is musical animation perfection.

Over the next 10 years, Guaraldi would score numerous “Peanuts” television specials, plus the feature film “A Boy Named Charlie Brown.” Then in 1976, it sadly ended. In a break during a live performance at Menlo Park , California, Guaraldi died from an apparent heart attack. He was 47

Although Guaraldi was working on another “Peanuts” special at the time of his death, his first score, “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” is still his most famous and most popular work.

The soundtrack released shortly after the special in 1965 and reissued in several formats since, remains one of the top selling Christmas albums of all-time.

(Sources: Animation Magazine – Lee Mendelson, Producer of This is America, Charlie Brown and all of the other Peanuts primetime specials – Sarah Gurman June 1st, 2006; various internet sites).

Why ‘Jingle Bells’ Isn’t a Song about Christmas at all.

By Ken Zurski

There just isn’t much Christmas in the song “Jingle Bells.”

In fact the word Christmas, Santa Claus or anything else holiday related isn’t included in the song at all. Basically, it’s about sleigh riding. More specifically, one could say, it’s about sleigh racing. After all, “dashing through the snow” didn’t mean taking a leisurely glide through the countryside.

And sleigh racing, for the most part, meant gambling.

True, the words “laughing” and “joy” is included in the song and the connotation of the word “jingle,” especially around Christmas, is more festive than alarming. Still, the original song evokes a more serious tone and the so-called “jingle bells,” well, they were there for a specific reason.

More on that in a moment.

First the backstory behind this curious tune.

James Lord Pierpoint, a New Englander, is credited with authoring “Jingle Bells.” Some suggest he wrote it in honor of the Thanksgiving feast rather than Christmas, which is unlikely on both counts. After all, how many carols were being written specifically about Thanksgiving?

Roger Lee Hall, a New England based music preservationist, does not refute or confirm the Thanksgiving theory only reiterates that Pierpoint may have written the song around Thanksgiving time, but probably not about it.

But like the lack of any Christmas themes, the song does not invoke the spirit of food or sharing – only a time and place. So at least the snow fits, especially in the upper east. In this case, Medford, Massachusetts, Pierpoint’s hometown.

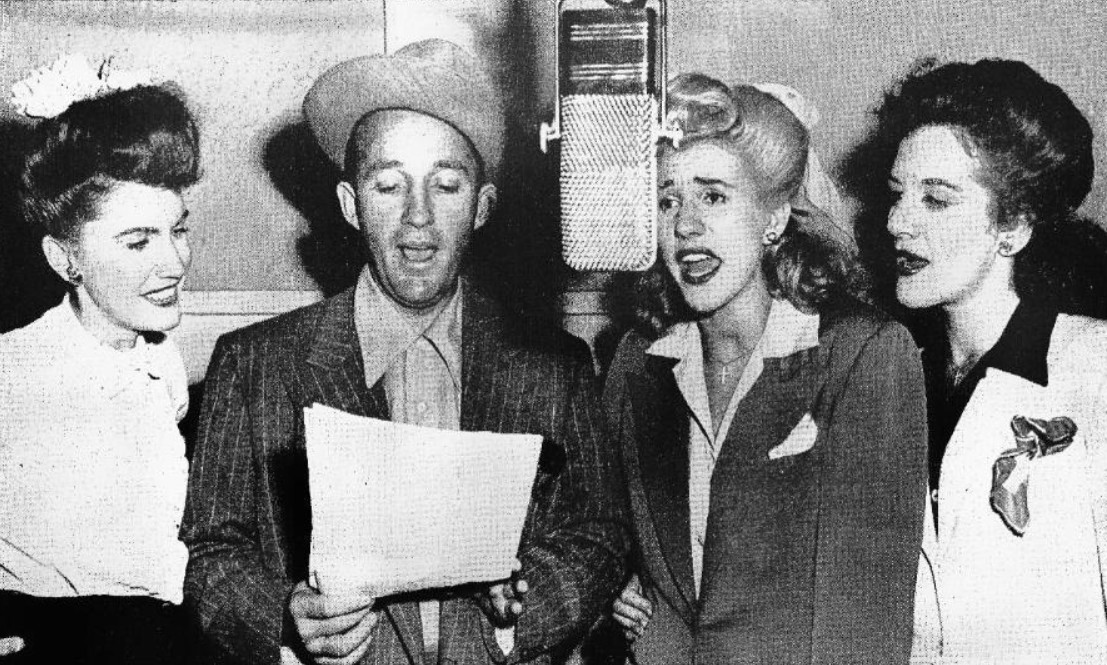

The song was originally released as “One Horse Open Sleigh” and later changed to “Jingle Bells or One Horse Open Sleigh.” Eventually, it was shortened to ‘Jingle Bells.” Copyrighted in 1859, the first recorded version of “Jingle Bells” was on an Edison Cylinder in 1898. Popular orchestra leaders like Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller did big band renditions of the song in the 1930’s and 40’s and crooner Bing Crosby would record it in 1943.

Crosby’s bouncy version with the Andrew Sisters is still considered a holiday favorite.

The first arrangement of “Jingle Bells”, which was less upbeat, is different than the one we hear today. Early on, it is said, “Jingle Bells” was featured in drinking establishments, and sung by men who would clink their tankards like bells when the word “bells” was mentioned.

In stark contrast. “Jingle Bells” is also reported to have been honed for a Sunday service since Pierpoint was the son of a minister. But as others point out, the song may have been too “racy” for church.

Obviously, we don’t hear the “racy” part in the modern version. Many of the original lyrics and several verses are eliminated completely. Only the first and familiar verse of the song is heard and usually repeated several times:

Dashing through the snow

In a one-horse open sleigh

O’er the fields we go

Laughing all the way

Bells on bobtail ring

Making spirits bright

What fun it is to ride and sing

A sleighing song tonight!

In one unfamiliar verse, the rider and his guest, a woman friend named “Fanny Bright,” get upended, or “upsot” (meaning capsized) by a skittish horse:

The horse was lean and lank

Misfortune seemed his lot

He got into a drifted bank

And then we got upsot.

In another verse, a similar mishap is ridiculed by a passerby:

A gent was riding by

In a one-horse open sleigh,

He laughed as there I sprawling lie,

But quickly drove away.

The chorus is then sung similar to what we know it today:

Jingle bells, jingle bells,

Jingle all the way;

Oh! what joy it is to ride

In a one-horse open sleigh.

(The word Joy was eventually replaced by “fun” in later versions.)

The last verse references the races:

Just get a bobtailed bay

Two forty as his speed

Hitch him to an open sleigh

And crack! you’ll take the lead.

Today, “Jingle Bells” evokes cheerful laughter and joy and is often associated with Santa’s reindeer, so the term has certainly transcended its original meaning.

But the true purpose of the bells is much more alarming – quite literally.

Sleighs made no sound as they glided over the snow, so the bells were used to warn others they were coming.

Hear jingly bells ringing? Get the heck out of the way.

Or else.

Oh, what fun!

Note: A Barbara Streisand version of “Jingle Bells” includes several of the original verses not usually heard on contemporary versions. She even includes a “Hey!” at the end of chorus as if she was raising a glass in tribute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CYpiWAoNVLg