Unrememebered History

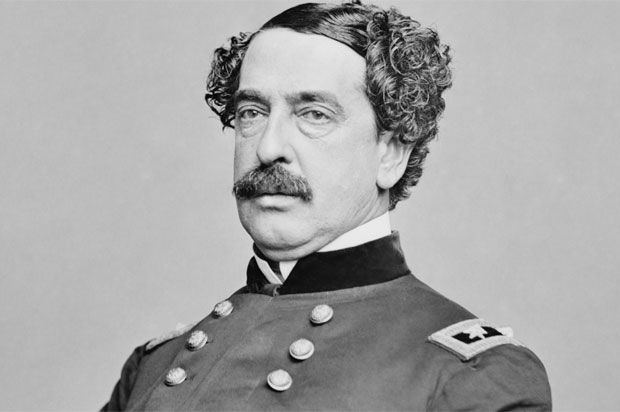

The 16th Century ‘Turnspit’ Kitchen Dog

By Ken Zurski

The history of working dogs go way back, centuries in fact to the age of the Vikings, who used the strong, stout breeds for hunting and herding cattle. Some of these breeds, including the Nork or Norwegian Elkhound, remain viable even today.

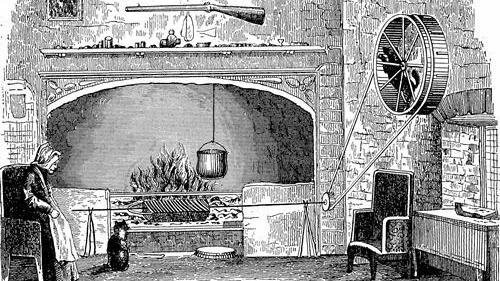

But perhaps no other breed better exemplifies the skill and resiliency of a working dog more than the turnspit, or kitchen dog, whose job it was to turn the spit and cook the meat over a roasting fire.

This was accomplished by a wooden wheel that was mounted on the wall and connected by ropes to the spit in front of the fireplace. The dog would be hoisted on the wheel and begin to run, similar to a hamster in a cage. As the dog ran, the wheel spun, the spit turned, and the meat cooked evenly. To keep the dog from overheating or fainting, the wheel was placed just far enough away from the heat and sparks. And when a dog tired another dog would be ready to take its place.

Until the 16th century when turnspit dogs were introduced, the turning of the cooking spit was the responsibility of a lowest ranking family member, usually the youngest child and almost always a boy. The job was grueling and often resulted in burns, blisters, sores or worse. Dogs were just a better option. Plus they could work longer and would ask for nothing more than to be fed.

Descriptions vary a bit but the overall picture of a “turnspit” paints a dog with short or crooked legs, a heavy head, and dropping ears.

They were low-bodied, strong, sturdy and as one dog historian notes, endured cruel punishment. To train the dog to run faster, oftentimes a burning coal was thrown into the wheel.

In 1750, turnspits were reportedly everywhere in Great Britain. (There are only a few instances that show them in America.) A century later, in 1850, the turnspit breed was nearly gone. The availability of cheaper spit-turning machines, called clock jacks, replaced the turnspits. And since the dogs were considered unappealing and mostly unfriendly, no one kept them as pets. Today the extinct breed is compared to a Welsh Corgi, although its similarities are in looks only.

According to sources, the turnspit dogs would get one day off from the wheel: Sunday.

Not for any spiritual connotation, mind you, but for another useful purpose.

They made good foot warmers in drafty church pews.

“Whiskey,” a taxidermied turnspit dog on display at the Abergavenny Museum in Wales.

For a Long, Long Time No One Knew who ‘Betsy Ross’ Was

By Ken Zurski

In 1752, in Philadelphia on New Year’s Day, Elizabeth Griscom was born to a strict Quaker family who emigrated to the United States from England in the late 17th century.

A free spirit in her twenties, Elizabeth ran off and met John Ross an upholsterer’s apprentice and an Episcopalian. Her parents forbade the union outside the Quaker faith, but Elizabeth didn’t care. She married John in a ceremony that took place in a tavern and formally became Elizabeth Ross or “Betsy,” for short.

Today, Betsy Ross is certainly name we recognize.

So much so that in contemporary surveys, many people acknowledge the name Betsy Ross more than interminable historical stalwarts like Benjamin Franklin or Christopher Columbus. However, until her name became synonymous with America’s symbol of freedom, Betsy Ross was a sister, a mother, a widow (three times over), a seamstress, and by the time the rest of the country got to know her – dead for nearly 50 years.

If there was something special about her life, a slice of American folklore, perhaps, she told her family and no one else.

In 1870, however, that would change.

That year, Ross’s last surviving grandson William Canby went before the Historical Society in Philadelphia and told an amazing story about his grandmother, General George Washington, and the birth of the American Flag.

According to Canby, Washington had visited Ross’s upholstery shop in Philadelphia with a sketch idea for a unified flag and asked if Betsy could recreate it. “With her usual modesty and self-reliance,” Canby related, “she did not know, but said she could try.”

Canby says among other revisions, Betsy suggested that the stars be five-pointed rather than six as Washington had proposed (Washington thought the six-pointed star would be easier to replicate). The story was as revealing as it was skeptical. No one had heard of Betsy Ross and previous stories of the first flag was apocryphal at best. There were many nonbelievers and even today historians have doubts. There are no records to support Canby’s claim, they insist, even though Canby had signed affidavits to back up his story.

At the time of Washington’s proposed visit in 1777, Ross would have been in her 20’s. Her life was typical for a young women at the time. She endured two marriages that ended tragically (her first and second husband’s death were both attributed to war.) A third marriage produced five children. She passed away in 1836 at the age of 84. There is no documentation that she publicly promoted her own role in making of the flag – or was even asked. Apparently only her family knew.

Nearly a century later, however, in the midst of the Reconstruction period, a changing nation embraced Canby’s story of his grandmother and Ross became the face of America’s first flag. The early flag became affectionately known as “The Betsy Ross Flag,” and trinkets of the thirteen stars and stripes were a big seller.

Even hardened critics, who claim many seamstresses may have played a role in the flag’s creation are willing to concede, for history’s sake at least, that one name gets credit for the five-pointed stars.

Betsy Ross.

Thanks to Sousa’s Brain Band, ‘The Stars and Stripes Forever’ Came Quickly

By Ken Zurski

Bandleader and composer John Philip Sousa was never one to hurry a piece of music. A tune would come to him and he would play it over and over in his mind until it was just right – or as he called it, the “brain band” would perform it in his head before a single note was ever recorded.

That’s exactly what happened in 1896, while Sousa was returning from a trip overseas.

Sousa was forced to cut the trip short after receiving news that his longtime manager had passed away. Pacing the deck of the steamer Teutonic, Sousa heard a tune in his head and the “brain band” took over.

“Day after day,” he said,” as I walked, it persisted in crashing into my very soul.”

When Sousa returned to America, he set it to paper: “It was a genuine inspiration, irresistible, complete, and definite and I could not rest until I had finished the composition.”

“The Stars and Stripes Forever” quickly became Sousa’s most popular march.

This Uninhabited Island is a Good Thing for the Sport of Curling

By Ken Zurski

Thanks to a small island just off of mainland Scotland in an area known as the Firth of Clyde, a sport which date backs to the early 19th century continues to prosper.

They don’t play the sport of Curling there, nor does anyone actually live there. It’s currently uninhabited by humans. But its resource, the Blue Hone Granite is used for making the stones that gives Curling its unique name, as in the curl of a spinning stone over an icy surface.

Fairy Rock

The 60 million year old island named Ailsa Craig which in Gallic means “Fairy Rock,” although other alternative interpretations include the less fanciful and more directly expressive definition of “Cliff of the English,” is the plug of an extinct volcano. Monks, castles, chapels, a prison and lighthouses are all part of its lore. In the early 15th century the Ailsa Craig Castle was owned by the monks of Crossraguel Abbey.

But lately, it’s known for two things: birds and curling stones.

The island is exclusively a bird sanctuary. Puffins and gannets use Ailsa Craig as a breeding ground. This is fairly recent development and only after an infestation of rats first introduced to the island during shipwrecks, were eradicated in the early 1990’s. Once the rats were gone, the birds came back.

Blue Hone

Since 1851, however, the company Kay’s of Scotland, named after its founder Andrew Kay, who established the first curling stone manufacturing business over a hundred years ago, has been harvesting the granite boulders from the island to use in curling stones. Only two places on earth is said to have the Blue Hone or Common Green granite which has a low absorption rate and keeps water from freezing and eroding the stone: Ailsa Craig and the Trefor Granite Quarry in Wales.

Even today, 60-70 percent of all curling stones comes from granite extracted from Alisa Craig. The company says the last harvest of granite from the Island took place in 2013 when 2,000 tons were extracted, sufficient to fill orders until at least 2020.

Recent efforts have been made to reduce the dependency of the centuries old island as the only supplier of the curling stones, but a plastic substitute and a denser granite found in Canada are relatively new developments and not yet widely accepted or used in the sport.

Not yet, at least.

The Cheese

All this is good news for a sport which has seen a popularity surge in the past decade, especially in North America.

After all, before the discovery of granite on Ailsa Craig, stones used for curling were made of whinestone, often basalt, which was cut into a circular shape called “The Cheese” and weighed 70 pounds or more.

The current stone weight is just under 50 pounds.

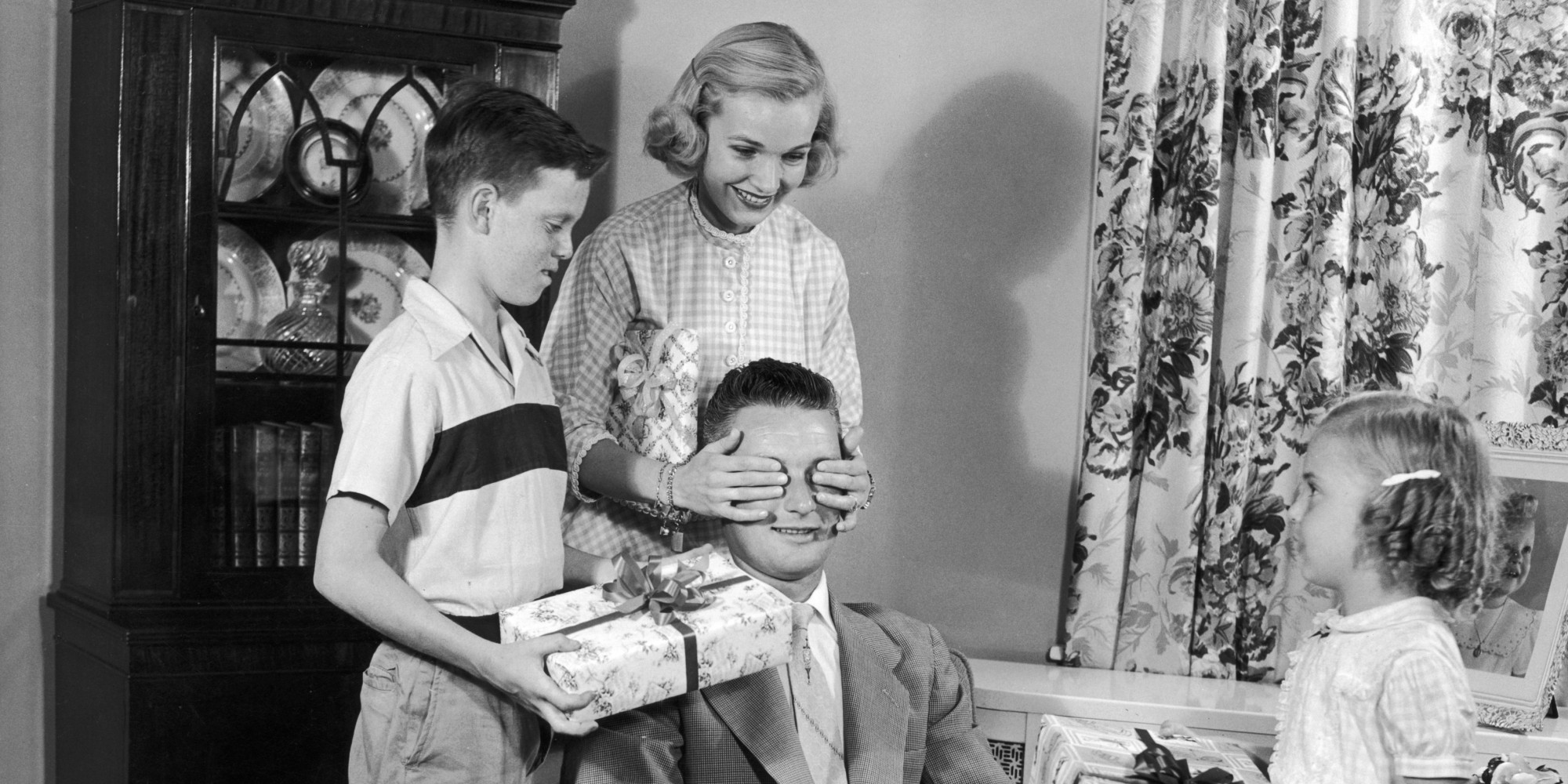

The Origins of Father’s Day: A ‘Second Christmas’ for Dads

By Ken Zurski

Nearly every May in the 1930’s, a radio performer named Robert Spere staged rallies in New York City promoting a day set aside not just to honor moms, but dads as well.

His hope was to change “Mother’s Day” to “Parent’s Day” instead.

Spere, a children’s program host known as “Uncle Robert” told his attentive audience: “We should all have love for mom and dad every day, but ‘Parent’s Day’ is a reminder that both parents should be loved and respected together.”

Spere was onto to something, but it would have to wait.

Much earlier, in 1908, a day set aside to celebrate mom, affectionately known as Mother’s Day, became a national day of observance. But there was no enthusiasm for a day set aside for fathers. “Men scoffed at the holiday’s sentimental attempts to domesticate manliness with flowers and gift-giving,” one historian wrote.

Retailers, however, liked the idea. They promoted a “second Christmas” for dads with gifts of tools, neckties and tobacco, instead of flowers and cards. But it never gelled. Even Spere’s “Parent’s Day” idea hit a snag when the Great Depression hit. (Today, “Parents Day” is officially celebrated on the fourth Sunday of every July.)

In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed a proclamation honoring fathers on the third Sunday of June.

Six years later, in 1972, with President Richard Nixon’s signature, “Father’s Day” officially became a national holiday.

John Banvard and the ‘Three-Mile Painting’

By Ken Zurski

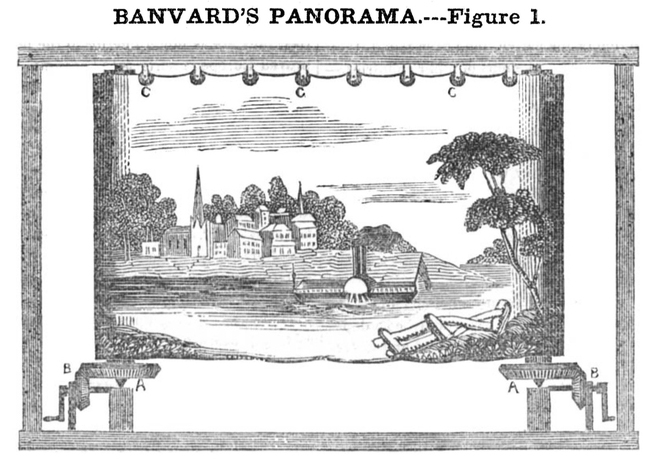

In the 1840’s, artist John Banvard created the largest, longest and most ambitious painting of its time. Figuratively rather than literally, it was named “Three-Mile Painting” because it consisted of a series of large painted scenes in sequence called a “moving panorama.”

Banvard chose the continuous landscape of the Mississippi River as his subject. He spent two years on the river traveling by boat and hunting for food to survive. He sketched hundreds of scenic vistas from St Louis to New Orleans and when finished holed himself up in Louisville, Kentucky to begin rolling and unrolling canvases. He then transferred the sketches at a breakneck pace.

It was as massive an undertaking as the subject itself.

Each panel stood 12 feet high and together stretched for 1300 feet – not quite a quarter of a mile in total. That was far short of the “three miles” Banvard had advertised, but who was counting?

Banvard presented the work to packed houses and appreciative audiences and in 1846, by request, brought the massive painting to England and Queen Victoria for a private showing in Windsor Castle.

Banvard made a fortune and took his success personally. He fought with fellow panorama artists calling them “imitators” and in return they called Banvard ”uncultivated.” When Banvard built a castle-like estate on 60 acres in New York’s Long Island, it was admonished by locals for being overtly excessive, pretentious and impractical. They called it “Banvard’s Folly.” It later became a lavish hotel.

In 1851, in direct competition with Banvard, another panorama depiction of the Mississippi River was presented by artist John L Egan. Although it was advertised as a whopping “15,000 feet” in length, a more factual estimate puts it closer to 348 feet. Each panel was 8- foot high and 14-feet long. The rolled canvas was so large that matinee viewers were treated to a stroll down the river’s stream in the afternoon while in the evening performance, as the canvas was rolled back in reverse, a trip upstream was presented.

While Banvard claimed to be first to showcase the wonders of the mighty river on canvas, Egan’s deception is better known today because its scenes have been saved, making it the last known surviving panorama of its time.

Unfortunately that is not the case with Banvard’s “Three-Mile Painting.” It was never persevered or copied. Because of its size and quantity, the panels were separated and used as scenery backdrops in opera productions.

When the canvases became worn from exposure they were shredded and recycled for insulation in houses.

Henry Ford, ‘The Vagabonds,’ and the Birthplace of the Charcoal Briquet

By Ken Zurski

In 1919, car-making giant Henry Ford had been eyeing a significant tract of land on the far western portion of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan known as Iron Mountain. Ford’s cousin, Minnie, to whom he was very close, lived there along with her husband E.G. Kingsford. Thanks to his wife’s family connections, Kingsford ran a successful timber business and owned several car dealerships in the area.

Kingsford, of course, is a name synonymous with charcoal briquets, but the backstory has just as much to do with Ford’s keen business sense.

Here’s why:

At the time, Ford had begun wrestling control from his stockholders and purchasing raw materials to be used in making his vehicles. Anything to make his car making process more efficient, he implied. Kingsford had a beat on something Ford desperately sought. So Ford invited Kingsford to go camping with him. To talk business, he explained.

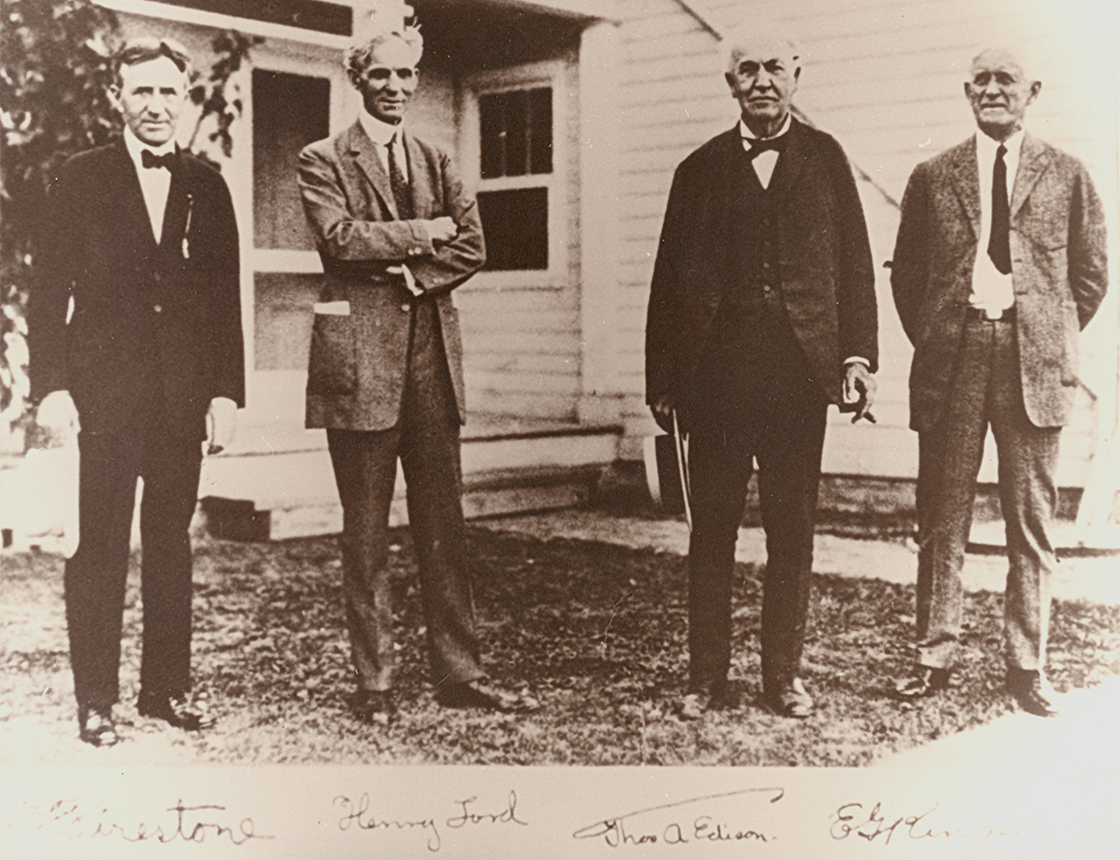

Ford had been making headlines across the country, not just for making cars, but for using one too. Ford went on road trips. The press dubbed it, “auto-camping,” because Ford along with his three close friends, who called themselves “the vagabonds” would travel by automobile during the day then set camps at night. Ford’s camping companions were no slouches. They included Harvey Firestone, the tire company founder; John Burroughs, the conservationist; and inventor Thomas Edison. Their journeys included a jaunt through the Florida Everglades and treks across mountainous regions in West Virginia and New England. Their first trip to the Adirondacks in 1918 was so satisfying they all agreed to make a trip to a new destination every year.

The trips were well-organized, well-stocked and oftentimes well-staffed with cooks and a cleaning crew. Like true campers, though, the formidable men did sleep on folding cots in a ten-by ten canvas tent. Burroughs, in his 80’s and the oldest by age of the four (Ford was in his 50’s), chronicled most of the adventures. He marveled at their resiliency. “Mr Ford seizes an ax and swings it vigorously til there is enough wood for the campfire,” he wrote.

Each year newspapers ran features of “the vagabonds” latest adventure and newsreels of their exploits were shown in movie theaters throughout the country. After all these were prominent American inventors and role models to some like Edison and Ford, who despite their gray hair, and unabashed preference to wear business attire – tight collars, three piece suits and ties – even on the retreats, were “roughing it,” so to speak, in the great outdoors. The papers couldn’t hide the obvious irony of it all. “Millions of Dollars Worth of Brains Off on Vacation,” the headlines blared. Even President Warren G. Harding joined the men briefly for one excursion.

Kingsford must have been pleased and a certainly flattered by Ford’s invitation to join “the vagabonds” in Green Island, New York, a popular fishing spot near Edison’s Machine Works company. Ford had a purpose. He needed land. Specifically, he needed land with timber on it. Nearly one-million board feet a day was used to manufacture the popular Model T’s, whose chassis were made mostly of wood.

Kingsford convinced Ford to buy some flat land near the Menominee River and build a wood distillation plant. Ford heeded his advice and went even further. He would build the plant and an electric dam nearby to power it. Ford hated to waste anything and in the wood distillation process there was always a lot of waste, specifically wood chip ash, or rough charcoal. So Ford had an idea. He mixed the crushed charcoal with a potato starch glue and pressed the blackened goo into a pillow-shaped briquette. When lit, it burned white ash and produced searing heat, but little or no flame.

Ford was not the first person to come up with the idea of charcoal in a briquet. That honor goes to a man named Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer from Philadelphia who patented the idea in 1897. Ford, however, was the first to commercially market it. He advertised the new product as “a fuel of a hundred uses” and perfect for “barbecues, picnics, hotels. restaurants, ships, clubs, homes, railroads, trucks, foundries, tinsmiths, meat smoking, and tobacco curing.” For home use, it was less dangerous than a traditional wood fire, but just as useful. “Briquette fire alone is enough to take the chill off a room,” the instructions informed. “Absence of sparks eliminates this menace to rugs, floors and clothing.”

Ford’s put his signature logo on the charcoal briquettes bags and sold them exclusively at his many car dealerships. When Ford died in 1947, the charcoal business was phased out. Henry Ford II took over and sold the chemical operation to local business men who changed the name to reflect its local heritage: Kingsford Chemical Company. By that time, Kingsford was not just a person, but a city. Thanks to the economical success of Ford’s wood, parts and charcoal plant, the land used to build the original timber business was named in honor of its first industrialist.

His story is rarely told. In short, Kingsford was born in Woodstock, Ontario and moved to Michigan as a young boy. He lived on his parents farm in Fremont before becoming a timber agent and moving to Marquette in the Upper Peninsula. In 1892, Kingsford married Mary Francis “Minnie” Flaherty, Henry Ford’s cousin. Several years later, he signed a contract to become a Ford sales agent in Marquette and eventually moved to Iron Mountain where he bought tracks of land for timber and opened several Ford dealerships. When Ford called to discuss the possibility of using the massive timber resource for his car making, Kingsford answered.

Eventually, the once uncharted land, about five square miles total, was named Kingsford, Michigan.

Despite the distinction, however, Ford, not Kingsford, is prominently associated with the town’s history. Ford was responsible for putting up the large factory, employing hundreds of workers, and building modern houses for the workers and their families to live. Within just one year, in 1920, the population of Kingsford blossomed from a mere 40 residents to nearly 3,000, creating a town out of an enterprise, thanks to Henry Ford.

By the time Ford’s imprint left in 1950, the town of Kingsford was established enough to persevere, although the plant’s closing was a blow economically. After the parts plant it’s doors in the 1960’s, the charcoal business also left; moving operations to Louisville, Kentucky.

Ford’s name is still displayed on several establishments in town: Ford Airport, Ford Hospital and Ford Park are just a few examples. In a a publication honoring the city’s 75th Jubilee, Kingsford is refereed to as “The Town that Ford Built.”

Some might say that’s a slight to Kingsford, the man, who by association convinced Ford to venture out to the remote section of the Upper Peninsula, ultimately invest in some land, and put a city on the map. Today, you have to go to Kingsford, Michigan to get the full story. You’ll see. Ford still gets the credit.

But when it comes to charcoal, we all know whose name is on that big blue and white bag.