History

Abraham Lincoln’s Eldest Son Has a Sea Named After Him

By Ken Zurski

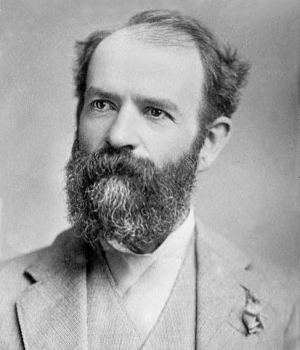

Robert Todd Lincoln, President Abraham Lincoln’s first son, outlived his father by 26 years. He also lived 19 years more than his mother, who died at the age of 63. As for his three younger brothers, tragically, they all died young, including the Lincoln’s third son, Willie, who succumbed to illness in the White House at the age of 11. Robert was a teenager at the time of Willie’s death. And yet, despite being the only Lincoln child to live to an old age, Robert’s adult life is understandably overshadowed by the legacy of his father.

But Robert Todd Lincoln lived a fascinating life of nearly 83 years. A life filled with military service, politics, great wealth and something he and not his famous father can claim: a sea named after him.

The 25-thousand square miles of the the Lincoln Sea encompasses a location between the Arctic Ocean and the channel of the Nares Strait between the northernmost Qikiqtaaluk region of Canada and Greenland. Scientists today will point out its geographical and oceanic importance, like most seas, but not much more.

It’s desolate, extreme, and doesn’t bear resemblance to a conventional sea at all. It’s almost completely covered with ice. Due to its year-round ice cover, not many have seen the Lincoln Sea up close, or make a point to visit. The nearest town in Nunavut Canada is so remote it is almost always uninhabited and appropriately named Alert, just in case someone may stumble upon it.

When most people find out there is a sea named Lincoln their immediate instinct is to conclude that it is in honor of the 16th president.

But it’s not.

Here’s why.

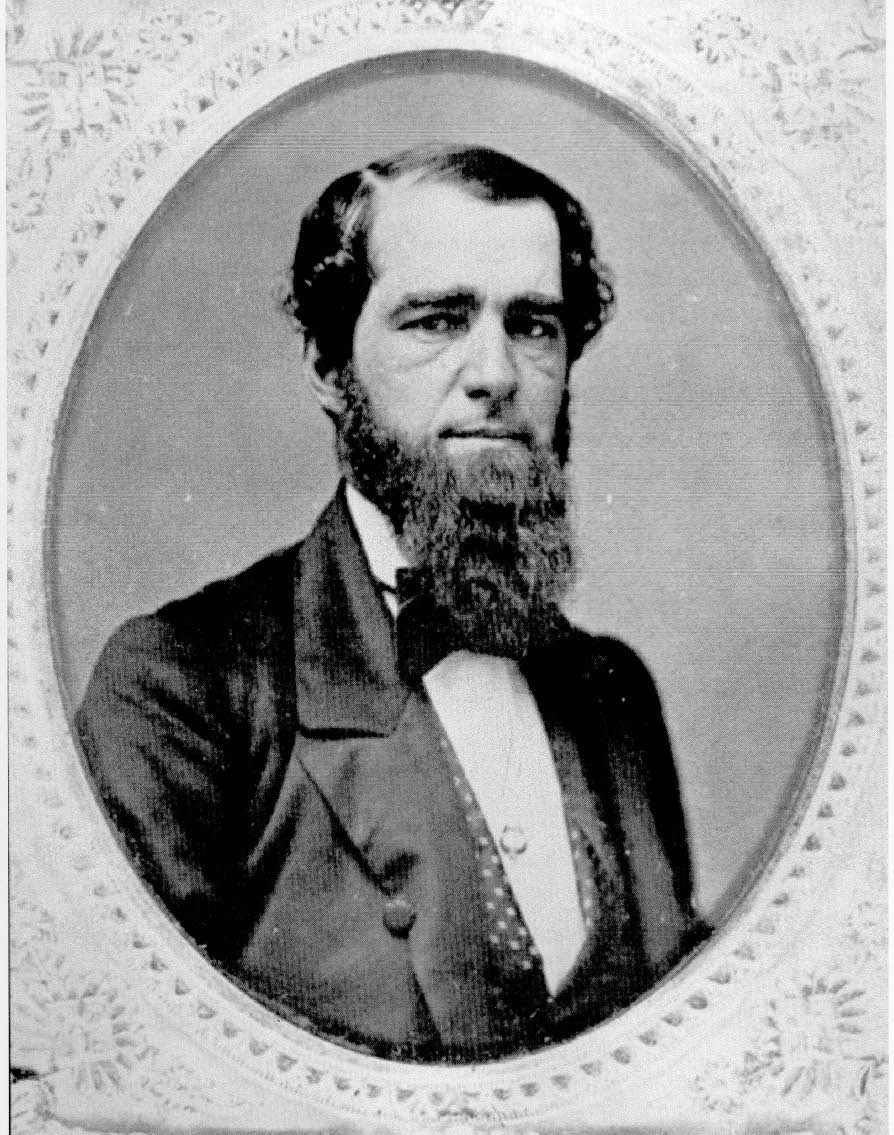

In 1881, Robert Todd Lincoln was President James Garfield’s Secretary of War when explorer and fellow soldier Lieutenant Adolphus Greely took a polar expedition financed by the government to collect astronomical and meteorological data in the high Canadian Arctic. A noted astronomer named Edward Israel was part of Greely’s crew. Secretary Lincoln reluctantly approved the risky venture.

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, as it was called, was mostly smooth sailing at first followed by a harrowing and deadly outcome. After discovering many uncharted miles along the northwest coast of Greenland including a new mountain range they named Conger Range, Lt. Greely and the crew of the Proteus were forced to abandon several relief sites due to lack of supplies. They retreated to Cape Sabine where they hunkered down for the winter with limited food rations.

Months later, in July of 1884, nearly three years after the expedition began, a rescue ship Bear finally reached the encamped crew. It was a sobering sight. In all, 19 of the 25-man crew, including Israel had perished in the harsh conditions.

Greely survived.

Even within his own department, Lincoln was criticized for not dispatching a second relief ship (the first one failed to make it through the ice). He rebuked the claims and defended his own actions by basing the decision on information provided to him by others. “Hazarding more lives,” as he put it, was not an option. Greely also blamed Secretary Lincoln for his crew’s fate.

But that was all. Most people understood how dangerous the mission was and Lincoln outlasted the backlash. He issued a court-martial for an outspoken War Department official named William Hazen, and gave Greely a pass, although the Lieutenant’s comments irritated him.

The naming of the Lincoln Sea was a bonus for the Secretary, of course. Although it’s easy to understand why Greely – if in fact he personally named the sea after his military boss – was motivated to do so, especially as the expedition was going well, his actions after the disastrous mission would suggest otherwise. No record exists as to whether Lincoln was flattered by the attribution.

The naming itself is odd. Since President Abraham Lincoln had hundreds of cities, institutions and streets named after him, including the town of Lincoln in Illinois, which was named for Lincoln, the lawyer, before he even became president, you would think the sea distinction would be more identifiable. Perhaps the Robert T. Lincoln Sea would have been more appropriate. But that’s not the case. It’s the Lincoln Sea, plain and simple, on maps and atlases and in literature. So the confusion with the President is understandable.

Robert Todd Lincoln continued to serve as Secretary of War after Garfield’s assassination and through successor Chester Arthur’s presidential term. Under Benjamin Harrison, he served a short stint as U.S minster to the United Kingdom and eventually left public service. In 1893, Lincoln invested in the popular Pullman rail cars, made a fortune, and lived comfortably for the remaining years of his life. He died on July 26, 1926, just six days shy of his 83rd birthday.

And whether he liked it or not, the ice-covered and relatively unknown Lincoln Sea, is a part of Robert Todd Lincoln’s legacy.

Not his father’s.

The Nimrod Effect: How a Cartoon Bunny Changed The Meaning of a Word Forever

texBy Ken Zurski

nim·rod: LITERARY a skillful hunter. INFORMAL•NORTH AMERICAN an inept person (Oxford dictionary)

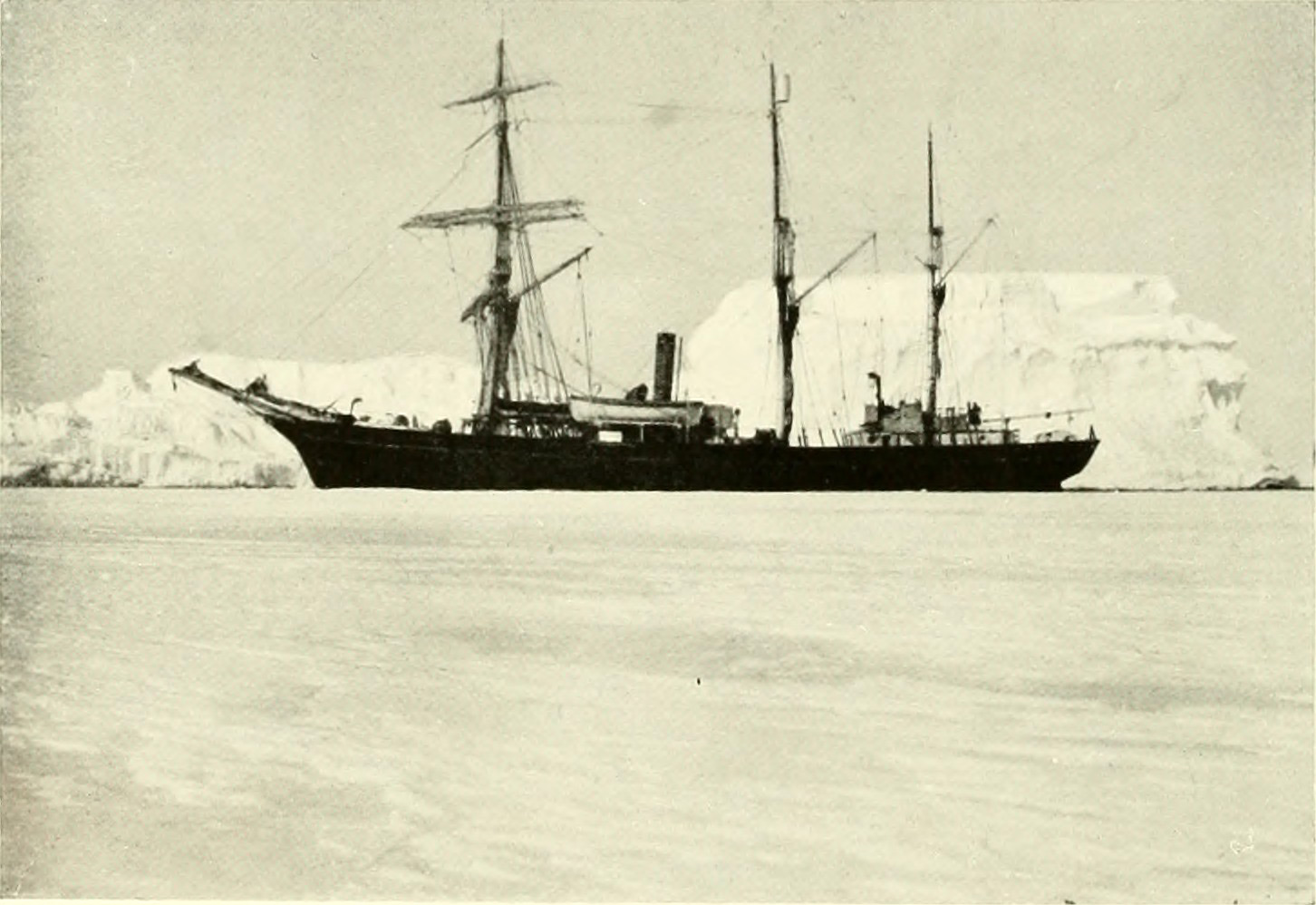

In 1909, British explorer and Antarctic specialist Earnest Shackleton became the first person to come as close to the South Pole as any human had possibly done. The goal of course was to reach the elusive Pole, but turning back shy by only 100 miles was an accomplishment worthy of another try at least. The fact that no one died in the expedition was even better.

Shackleton had christened the ship he chose on that journey by a term that reflected the mission’s quest. He named it Nimrod.

Yes, the Nimrod Expedition, despite its insinuation, was not a mission for dummies. That’s because the word “nimrod” at the time represented something very different than it does today. Back then, strength and courage was it’s core. A nimrod was someone who was held in high regard. The name demanded respect.

Shackleton’s hand picked ship, Nimrod, lived up to its moniker too, a reference to Nimrod, the biblical figure and “mighty hunter before the Lord” from the Book of Genesis. Nimrod was an older boat and needed work, but Shackleton had little recourse with limited funds. He would eventually praise the small schooner as “sturdy” and “reliable.”

Even before Shackleton’s journey, the term nimrod was being used to promote other noteworthy ventures. Financier and cutthroat ship builder Cornelius Vanderbilt named a steamboat Nimrod to compete with other commuter boats on New York’s Hudson River. It had to be built stronger and faster than others, Vanderbilt instructed. No doubt the naming of the ship reflected this too.

In 1899, composer Edward Elgar wrote a symphonic piece that had 14 variations each written for or about a personal acquaintance.

The ninth variation was titled Nimrod.

“An amusing piece,” Elgar said referring to his friend and subject, August Johannes Jagear, a music publisher and accomplished violinist. Rather than a slight, however, it was a compliment. Jäger in German meant “hunter.”

In 1940, however, everything about the word changed.

It’s widely reported that during a cartoon short titled “A Wild Hare,” a wise-cracking rabbit named Bugs Bunny called his nemesis Elmer Fudd a “poor little nimrod,” a sarcastic reference to Fudd’s skills as a hunter. Whether Bugs actually said it or it was Daffy Duck who called Fudd a “nimrod” is debatable. Bugs would get credit (it was after all a Bugs Bunny cartoon).

In context the use of the word meant to mock Fudd’s foolhardy abilities which kept the rabbit, Fudd’s prey, out of his cross hairs, so to speak.

Most children didn’t get the reference to Nimrod in biblical terms and the sarcasm went way over their heads. So the word became synonymous with a bumbling fool, like Fudd’s character.

At least that’s the story.

Today, as we examine the word’s usage more closely, a nimrod may have been the implication, but certainly not the description of Shackleton and his Antarctic crew. Those who wished to board the Nimrod, some might say, were playing a fools game. After all who was crazy enough to go?

Shackleton didn’t hide the discomforts and dangers of the mission when he advertised for a team of men and warned of a “hazardous journey” with “low, wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness.” If they made it back, which was “doubtful,” Shackleton expressed, “honor and recognition” would await them upon return.

Basically, only Nimrod-types need apply, he suggested.

Good thing Bugs Bunny wasn’t around to discourage them.

![]()

The Introduction of a Mrs. Claus is a Real Tearjerker

By Ken Zurski

“The Christmas Legend” is a short story written in the mid-nineteenth century by a Philadelphia missionary named James Rees. It tells the tale of a destitute American family that receives an unexpected visit from a couple of strangers on Christmas Eve. The constructive narrative sets up a deep exploration of family, loss and forgiveness; a classic Christmas formula. But the story itself is not widely known. In fact it would likely be completely forgotten had it not been for one word- “wife.” Today, it is cited as being the first time Santa Claus was associated with a spouse. It literately introduced the character we know now as Mrs. Claus.

“The Christmas Legend” is a short story written in the mid-nineteenth century by a Philadelphia missionary named James Rees. It tells the tale of a destitute American family that receives an unexpected visit from a couple of strangers on Christmas Eve. The constructive narrative sets up a deep exploration of family, loss and forgiveness; a classic Christmas formula. But the story itself is not widely known. In fact it would likely be completely forgotten had it not been for one word- “wife.” Today, it is cited as being the first time Santa Claus was associated with a spouse. It literately introduced the character we know now as Mrs. Claus.

Published in 1849, “The Christmas Legend” was part of a collection of 29 short stories written by Rees and compiled under the title, “Mysteries of City Life, or Stray Leaves from the World’s Book.” Each story is cleverly presented to represent the dissimilarity of many leaf types. For example, the maple leaf, Rees writes, is “golden and rich” and presents a sunnier disposition, while another like the gum tree leaf has a “bloody hue” and “stands fit emblem of the tragic muse.” He likens authors after the “forest trees” which “send forth their leaves unto the world.”

“And by what emblem shall we appear amongst those clustering trees,” Rees explains. “Let us see – Ah! The Ash Tree leaves are like ours, humble and plain to see, but hiding the silver underneath.”

In “The Christmas Legend,” Rees uses the spirit of the holiday to emphasis this point.

Here is the abbreviated story…

A family of four, mother and father, daughter and son, are sitting near the fireplace on Christmas Eve. The two children, especially the daughter, wonders if she should hang the stockings for Kris Kringle to come. But her mother raises doubt. There are more important things in life than earthly possessions, she states: “Poverty keeps from the humble door all the bright things of the earth, except virtue, truth and religion, these are more of heaven and earth, and are the poor man’s friend in time of adversity.”

“I thought that Santa Claus or Kris Kringle loved all those who are good, and haven’t I been good?” the daughter asks confused.

The mother tells her to leave the stocking up. “Customs at least should be observed, and perhaps the young heart may not be disappointed,” she explains.

The father is more introspective. He anguishes over a lost family member, the eldest child, another daughter who apparently ran away with a “dissipated” man seven years before and hasn’t been seen or heard from since.

Then there is a knock at the door.

Two strangers appear out of the night, an elderly couple carrying a bundle with “all their worldly wealth.” They ask how far away they are from the city and the father tells them it is “two miles.”

“Two miles?” the stranger says sadly, “we will not be able to reach it tonight. My dear wife is nearly tired out. We have traveled far today.”

The father invites them in and offers his best bed for them to rest. The strangers inquire if this is their whole family. “No. No,” the father says, “we had one other – a daughter.”

“Dead; Alas we all must die,” the old woman responds.

“Dead to us,” the man answers. “But not to the world. But let us speak of her no more. Here is some bread and cheese, it is all poverty has to offer, and to it you are heartily welcome.”

There is a silent pause, then the sound of cheerful merriment, music and laughter, is heard through the open windows and doors. It’s their rich landlord, the father explains, mocking the poor. The old man interjects. “Ah, sir, human nature is a mystery, this is one of the enigmas, and can only be explained when the secrets of the hearts be known.”

The next morning, Christmas Day, the family awakes to find their small room filled with presents: books and games and toys. “O Father, Kris Kringle has been here,” the little girl says excitedly. “I am so happy.”

Here Rees as the narrator sets up the moral of the story. “There are moments when the doors of memory and the bright sunshine of hope make the future all clear,” he writes. “Sorrow is not eternal; it has its changes, its stops; its antidote; they came in the moment of trial and – Presto! The whole scene of life is venerated in the pleasing colors of fancy.”

And that’s when something totally unexpected occurs. The old couple reappears to the family not as as they came, but as a vibrant young couple. The children recoil from fright, but the parents are curious. “How is this?” the father asks. “Why these disguises —“

“Hush, sir,” the once old man says laughing. “This is Christmas morn and we now appear to you not as Santa Claus and his wife, but as we are, the mere actors of this pleasing farce.”

The couple recognizes the old woman’s new face. It’s their long lost daughter. The girl hugs her mother, but the father is more skeptical, angry and weary of atonement. He lashes out at the girl as she approaches him. “Stand back!”, he shouts, then chastises the man who stands with her as a “paramour.” She begs him to reconsider. “No Father he is my kind and affectionate husband.”

“Ah, husband,” the father replies. He reaches for his daughter. They embrace.

Rees goes on to explain the girl ran away because she was “young and foolish” but loved the man who was forbidden from her home. They left America for England where her new husband became heir to a large estate. She sent letters home, but they were never received. Now she had returned back to her family on Christmas Day. A gift of love and hope. “Can you forgive me?” she asks.

“Say no more, all is forgotten. All is forgiven,” the father tells her.

Even though it is thinly defined, the mention of Santa Claus’s wife in “The Christmas Legend” is widely considered the first ever to appear in print. Two years later in 1851, the name Mrs. Santa Claus would be mentioned again in a story published in the Yale Literary Magazine. History tells the rest.

Today Mrs. Claus is considered a kindly old woman who helps her husband on Christmas Eve, tends to his colds, stitches his clothes, and feeds his “round belly,” usually with homemade cookies and milk.

“There are many interesting facts both historic and fabulous connected with the ceremonies, customs and superstitions of this day [Christmas], which if collected together today would make and curious and interesting book.” Rees explains in the introduction to his tale.

Apparently, he added to that.

Haddon Sundblom: The Man Behind the Classic Santa Look

By Ken Zurski

In the 1930’s when soft drink giant Coca-Cola decided to celebrate the holiday season in their promotional ads, American aritst Haddon Sundblom created an image that still today is considered the definitive appearance of a modern day Santa Claus.

For Sundblom, achieving such lasting notoriety was not entirely unexpected. The popularity of Coca-Cola products made images that appeared in their ads cultural phenomenons. In 1930, when Coke introduced Christmas-themed ads, another artist named Fred Mizen did a painting that featured the world’s largest soda bar at the Famous Barr Co. in St Louis, Missouri. In it, Santa Claus, presumably a store Santa, is seen in the crowd drinking a Coke while children stand by his feet.

The painting was interesting enough, just not memorable.

The next year, Coca-Cola wanted to portray Santa again. Something more refined. Something that focused on the man rather than the crowd.

Sundblom was asked to give the image a go.

Based on Clement Clark Moore’s descriptions of St. Nick in “’Twas the Night Before Christmas,” Sundblom’s Santa Claus emphasized the rosy cheeks and snow white beard along with the now familiar suit and hat. A wide leather belt and brown boots completed the look.

Santa is seen holding a Coca-Cola bottle like in the previous ads, but this time his face looked jolly, and his beard real. Even the “little round belly” was believable. The strikingly red and white suit in the new ad some claim was a request by Coke to emphasis the brands colors.

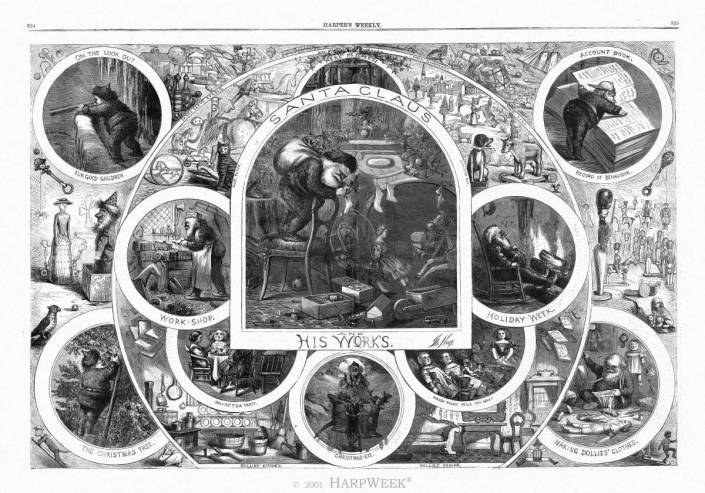

Sundblom’s Santa, however, was merely improving on an image already made famous nearly a decade earlier by illustrator Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly.

Nast genius was presenting Santa as a human figure, rather than a mysterious one. Santa had the suit (albeit drab) and a beard, but little detail. Most of his drawings were in simple ink and later colorized for Christmas cards.

Based on Nast’s early designs. Sundblom polished Santa’s bright and festive look for the soft drink company.

Sundblom went on to have a successful career in advertising art. In the mid 1940’s, shortly after the Santa image appeared, he created a colorized version of the Quaker Oats man, an image which still exists today, although it’s look has since been modernized.

Santa Claus, however, is still considered Sundblom’s most enduring figure.

And a “figure,” so to speak, was Sundblom’s specialty.

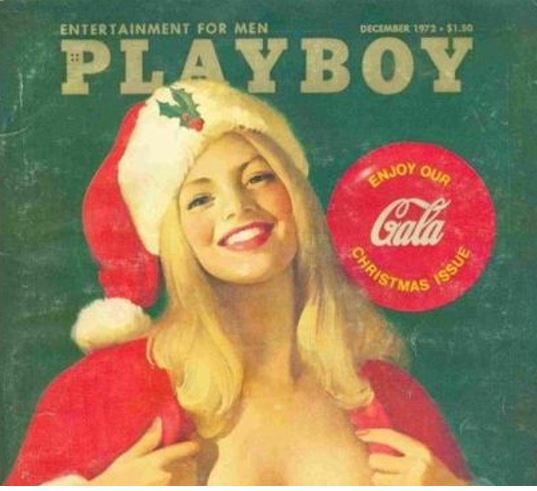

That’s because before he became associated with the holidays, Sundblom’s contracted work was in pin-ups, which featured detailed drawings of scantily clad women for magazine pull-outs and calendars. Coca-Cola must have known this at the time, but few made the connection. Then in 1972 at the age of 73, in what turned out to be his last assignment, Sundblom paid homage to both worlds.

That year, he was asked to draw a picture for the cover of the Playboy Christmas issue.

Typical of his pin-up work, Sundblom’s model is seen playfully removing an article of clothing.

This time, it was a familiar red coat.

The Golden Gate Bridge, Willie Mays, and the Inspiration For ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’

By Ken Zurski

In 1965, while traveling by taxi over the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, television producer Lee Mendelson heard a single version of “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” a Grammy Award winning jazz song written and composed by a local musician named Vince Guaraldi.

Mendelson liked what he heard and contacted the jazz columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Can you put me in touch with Guaraldi? he asked.

Mendelson was a producer at KPIX, the CBS affiliate in San Francisco at the time and had just produced a successful documentary on Giants outfielder Willie Mays. “For some reason it popped into my mind that we had done the world’s greatest baseball player and we should now do a documentary on the world’s worst player, Charlie Brown” Mendelson explained.

“I called Charles Schulz, and he had seen the [Willie Mays] show and liked it.” Mendelson’s mind raced with ideas. That’s when he took a taxi over the idyllic Golden Gate Bridge and was inspired by the music on the radio. Why not score the documentary with jazz music? he thought.

Mendelson called Guaraldi, introduced himself, and asked him if he was interested in scoring a TV special. Guaraldi told him he would give it a go. Several weeks later, Mendelson received a call. It was Guaraldi. I want you to hear something, the composer explained , and performed a version of “Linus and Lucy” over the phone.

Mendelson liked what he heard.

But the documentary never aired. “There was no place for it,” Mendelson said. “We couldn’t sell it to anybody.” Two years later soft drink giant Coca Cola contacted Mendelson and inquired about sponsoring a “Peanuts” Christmas special. “I called Mr. Schulz and I said ‘I think I just sold A Charlie Brown Christmas,’ and he said ‘What’s that?’ and I said, ‘Something you’re gonna write tomorrow.”

Mendelson decided to use Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy,” which had already been composed for the documentary. “The show just evolved from those original notes,” Mendelson described.

The rest is musical animation perfection.

Over the next 10 years, Guaraldi would score numerous “Peanuts” television specials, plus the feature film “A Boy Named Charlie Brown.” Then in 1976, it sadly ended. In a break during a live performance at Menlo Park , California, Guaraldi died from an apparent heart attack. He was 47

Although Guaraldi was working on another “Peanuts” special at the time of his death, his first score, “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” is still his most famous and most popular work.

The soundtrack released shortly after the special in 1965 and reissued in several formats since, remains one of the top selling Christmas albums of all-time.

(Sources: Animation Magazine – Lee Mendelson, Producer of This is America, Charlie Brown and all of the other Peanuts primetime specials – Sarah Gurman June 1st, 2006; various internet sites).

Why ‘Jingle Bells’ Isn’t a Song about Christmas at all.

By Ken Zurski

There just isn’t much Christmas in the song “Jingle Bells.”

In fact the word Christmas, Santa Claus or anything else holiday related isn’t included in the song at all. Basically, it’s about sleigh riding. More specifically, one could say, it’s about sleigh racing. After all, “dashing through the snow” didn’t mean taking a leisurely glide through the countryside.

And sleigh racing, for the most part, meant gambling.

True, the words “laughing” and “joy” is included in the song and the connotation of the word “jingle,” especially around Christmas, is more festive than alarming. Still, the original song evokes a more serious tone and the so-called “jingle bells,” well, they were there for a specific reason.

More on that in a moment.

First the backstory behind this curious tune.

James Lord Pierpoint, a New Englander, is credited with authoring “Jingle Bells.” Some suggest he wrote it in honor of the Thanksgiving feast rather than Christmas, which is unlikely on both counts. After all, how many carols were being written specifically about Thanksgiving?

Roger Lee Hall, a New England based music preservationist, does not refute or confirm the Thanksgiving theory only reiterates that Pierpoint may have written the song around Thanksgiving time, but probably not about it.

But like the lack of any Christmas themes, the song does not invoke the spirit of food or sharing – only a time and place. So at least the snow fits, especially in the upper east. In this case, Medford, Massachusetts, Pierpoint’s hometown.

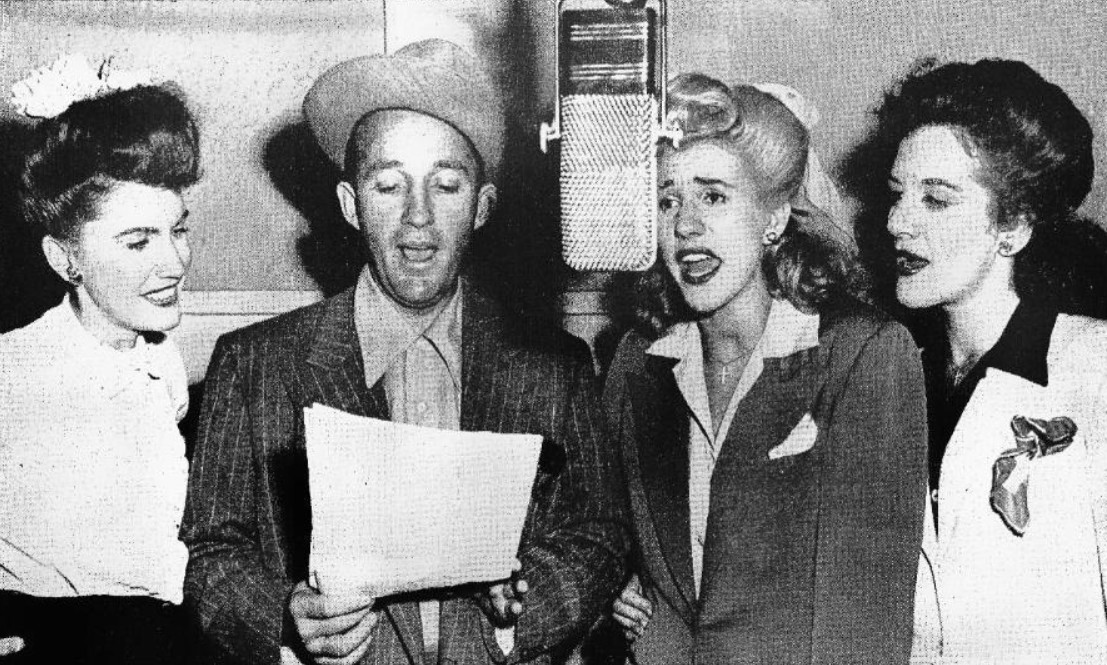

The song was originally released as “One Horse Open Sleigh” and later changed to “Jingle Bells or One Horse Open Sleigh.” Eventually, it was shortened to ‘Jingle Bells.” Copyrighted in 1859, the first recorded version of “Jingle Bells” was on an Edison Cylinder in 1898. Popular orchestra leaders like Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller did big band renditions of the song in the 1930’s and 40’s and crooner Bing Crosby would record it in 1943.

Crosby’s bouncy version with the Andrew Sisters is still considered a holiday favorite.

The first arrangement of “Jingle Bells”, which was less upbeat, is different than the one we hear today. Early on, it is said, “Jingle Bells” was featured in drinking establishments, and sung by men who would clink their tankards like bells when the word “bells” was mentioned.

In stark contrast. “Jingle Bells” is also reported to have been honed for a Sunday service since Pierpoint was the son of a minister. But as others point out, the song may have been too “racy” for church.

Obviously, we don’t hear the “racy” part in the modern version. Many of the original lyrics and several verses are eliminated completely. Only the first and familiar verse of the song is heard and usually repeated several times:

Dashing through the snow

In a one-horse open sleigh

O’er the fields we go

Laughing all the way

Bells on bobtail ring

Making spirits bright

What fun it is to ride and sing

A sleighing song tonight!

In one unfamiliar verse, the rider and his guest, a woman friend named “Fanny Bright,” get upended, or “upsot” (meaning capsized) by a skittish horse:

The horse was lean and lank

Misfortune seemed his lot

He got into a drifted bank

And then we got upsot.

In another verse, a similar mishap is ridiculed by a passerby:

A gent was riding by

In a one-horse open sleigh,

He laughed as there I sprawling lie,

But quickly drove away.

The chorus is then sung similar to what we know it today:

Jingle bells, jingle bells,

Jingle all the way;

Oh! what joy it is to ride

In a one-horse open sleigh.

(The word Joy was eventually replaced by “fun” in later versions.)

The last verse references the races:

Just get a bobtailed bay

Two forty as his speed

Hitch him to an open sleigh

And crack! you’ll take the lead.

Today, “Jingle Bells” evokes cheerful laughter and joy and is often associated with Santa’s reindeer, so the term has certainly transcended its original meaning.

But the true purpose of the bells is much more alarming – quite literally.

Sleighs made no sound as they glided over the snow, so the bells were used to warn others they were coming.

Hear jingly bells ringing? Get the heck out of the way.

Or else.

Oh, what fun!

Note: A Barbara Streisand version of “Jingle Bells” includes several of the original verses not usually heard on contemporary versions. She even includes a “Hey!” at the end of chorus as if she was raising a glass in tribute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CYpiWAoNVLg

Bing Crosby’s Final TV Christmas Special Was Both Unusual And Memorable

By Ken Zurski

In September of 1977, a popular British model and actress named Twiggy appeared on Bing Crosby’s annual Christmas television special. The family holiday staple was being filmed in London that year because the 74-year-old Crosby happened to be in Great Britain for a concert tour.

Crosby recruited several British entertainers as guests on the special titled “Christmas in England.”

The London-born Twiggy was one.

Considered the “face of the 60’s” with a rail thin figure, short hair and strikingly large eyes, the teenage Twiggy was arguably the most recognized model in the world. Now in her late 20’s, Twiggy remained a multi-talented performer who picked up two Golden Globes for her work in The Boy Friend, a movie based on a musical set in the 1920’s about a theater group in England whose stage manager Polly (played by Twiggy) gets her big break when the leading lady literally, “breaks a leg.”

In the Christmas special, Twiggy and Crosby sing a tender version of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” Twiggy is refined, relaxed and clearly star struck. Crosby takes the lead on the song but the two trade verses and sing portions of the chorus together. Twiggy also appears in a sketch with Crosby and British actor Ron Moody, best known for his role as Fagin in the movie Oliver.

It was both unusual and memorable and those who worked on the special had no idea at time it would be Crosby’s last. Only a month after filming, in October, Crosby died from an apparent heart attack. The posthumously aired British-themed Christmas special would be his last. When the show was broadcast later that year, in December, viewers watched with a heavy heart.

In retrospect, Crosby’s duet with Twiggy is a bittersweet tribute to the late crooner. It’s done with class and professionalism, a trademark of Crosby with any singer. In this case, a British model, 40-plus years his junior. Twiggy’s performance is equally sentimental and tender.

But the performance is forgotten today.

However, another well-known British star – and an even more unlikely choice than Twiggy – would make a mark on the show that would last for years to come.

David Bowie initially turned down the request to be a guest on the special because he didn’t like the song choice of “The Little Drummer Boy.” He eventually agreed after Crosby’s musical arrangers wrote a new part of the song for him to sing, titled “Peace on Earth,” which he liked:

Peace on Earth, can it be

Years from now, perhaps we’ll see

See the day of glory

See the day, when men of good will

Live in peace, live in peace again

The two voices soared together.

“Ah, that’s a pretty thing, isn’t it?” Crosby remarked after the two superstars finished the song.

Others agreed.

Today, their version of “Peace on Earth/The Little Drummer Boy” is a holiday favorite.

The Real History Behind Black Friday: the Day and that Song

By Ken Zurski

Before Americans began rushing to stores the day after Thanksgiving and calling the shopping frenzy “Black Friday,” the term itself was used to describe a dark and devious part of our nation’s history.

One that was mostly forgotten until 1975 when a group named Steely Dan immortalized it in song. But still to this day. most people don’t know what the song is really about:

“When Black Friday comes

I stand down by the door

And catch the grey men when they

Dive from the fourteenth floor”

Here’s the story:

The original “Black Friday” begins with a man named Jay Gould.

A leather maker turned New York railroad owner, Gould was the youngest of six children, the only boy, and a scrawny one at that; growing up to be barely five feet tall. What he lacked in size, however, he made up for in ambition.

A financial whiz even as a young man, Gould started surveying and plotting maps for land in rural New York, where he grew up. It was tough work, but not much pay, at least not enough for Gould. In 1856 he met a successful tanner – good work at the time – who taught Gould how to make leather from animal skins and tree bark. Gould found making money just as easy as fashioning belts and bridles. He found a few rich backers, hired a few men and started his own tanning company by literally building a town from scratch in the middle of a vacant but abundant woodland. When the money started to flow, the backers balked, accusing Gould of deception. Their suspicions led to a takeover. The workers, who all lived quite comfortably in the new town they built and named Gouldsborough, rallied around Gould and took the plant back by force, in a shootout no less, although no one was seriously hurt.

Gould won the day, but the business was ruined. By sheer luck, another promising venture opened up. A friend and fellow leather partner had some stock in a small upstate New York railroad line. The line was dying and the stock price plummeted. So Gould bought up the stock, all of it in fact, with what little earnings he had left, and began improving the line. Eventually the rusty trail hooked up with a larger line and Gould was back in business. He now owned the quite lucrative Erie Railroad.

Ten years later, in 1869, Gould turned his attentions to gold.

When Black Friday comes

I collect everything I’m owed

And before my friends find out

I’ll be on the road

Gold was being used exclusively by European markets to pay American farmers for exports since the U.S currency, greenbacks, were not legal tender overseas. Since it would take weeks, sometime months for a transaction to occur, the price would fluctuate with the unstable gold/greenback exchange rate. If gold went down or the greenback price went up, merchants would be liable -often at a substantial loss – to cover the cost of the fluctuations. To protect merchants against risk, the New York Stock Exchange was created so gold could be borrowed at current rates and merchants could pay suppliers immediately and make the gold payment when it came due. Since it was gold for gold – exchange rates were irrelevant.

Gould watched the markets closely always looking for a way to trade up. He reasoned that if traders, like himself, bought gold then lent it using cash as collateral, large collections could be acquired without using much cash at all. And if gold bought more greenback, then products shipped overseas would look cheaper and buyers would spend more. He had a plan but needed a partner.

He found that person in “Gentleman Jim Fisk.”

Jim Fisk was a larger than life figure in New York both physically and socially. A farm boy from New England, Fisk worked as a laborer in a circus troupe before becoming a two-bit peddler selling worthless trinkets and tools door to door to struggling farmers. The townsfolk were duped into calling him “Santa Claus” not only for his physical traits but his apparent generosity as well. When the Civil War came, Fisk made a fortune smuggling cotton from southern plantations to northern mills.

So by the time he reached New York, Fisk was a wealthy man. He also spent money as fast as he could make it; openly cavorted with pretty young girls; and lavished those he admired with expensive gifts and nights on the town. Fisk never hid behind his actions even if they were corrupt. He would chortle at his own genius and openly embarrass those he was cheating. He earned the dubious nickname “Gentleman” for being polite and loyal to his friends.

Fisk and Gould were already in the business of slippery finance. Besides manipulating railroad stock (Fisk was on the board of the Erie Railroad), they dabbled in livestock and bought up cattle futures when prices dropped to a penny a head. Convinced they could outsmart, out con and outlast anyone, it was time to go after a bigger prize: gold. There was only $20 million in gold available in New York City and nationally $100 million in reserves. The market was ripe for the taking and both men beamed at the prospects.

When Black Friday falls you know it’s got to be

Don’t let it fall on me

But the government stood in the way. President Grant was trying to figure out a way to unravel the gold mess, increase shipments overseas and pay off war debts. If gold prices suddenly skyrocketed, as Gould and Fisk had intended, Grant might consider a proposed plan for the government to sell its gold reserves and stabilize the markets; a plan that would leave the two clever traders in a quandary.

Through acquaintances, including Grant’s own brother-in-law, Gould and Fisk met with the president. In June of 1869, they pitched their idea posing as two concerned (a lie) but wealthy (true) citizens who could save the gold markets and raise exports, thus doing the country a favor. They insisted the president let the markets stand and keep the government at bay. Fisk even treated the president to an evening at the opera – in Gould’s private box. The wily general may have been impressed by the opera, but he was also a practical man. He told the two estimable gentlemen that he had no plans to intervene, at least not initially. But Grant really had no idea what the two shysters were up to.

A few months later, when Fisk sent a letter to Grant to confirm the president’s steadfast support, a message arrived back that Grant had received the letter and there would be no reply. The lack of a response was as good as a “yes” for Fisk. Grant was clearly on board, he thought.

He was wrong.

“When Black Friday comes

I’m gonna dig myself a hole

Gonna lay down in it ’til

I satisfy my soul”

On September 20th, a Monday, Fisk’s broker started to buy and the markets subsequently panicked. Gold held steady at first at $130 for every $100 in greenback, but the next day Fisk worked his magic. He showed up in person and went on the offensive. Using threats and lies, including where he thought the president stood on the matter, Fisk spooked the floor.

The Bulls slaughtered the Bears.

Gold was bought, borrowed and sold. And Fisk and Gould, through various brokers, did all the buying. On Wednesday, gold closed slightly over 141, the highest price ever. In his typical showy style, Fisk couldn’t help but rub it in. He brazenly offered bets of 50-thousand dollars that the number would reach 145 by the end of the week. If someone took that sucker proposition, they lost. By Thursday, gold prices hit an astounding 150. The next day it would reach 160.

Then the bottom fell out.

At the White House, Grant was tipped off and furious. On September 24, a Friday, he put the government gold reserve up for sale and Gould and Fisk were effectively out of business. Thanks to the government sell off, almost immediately, gold prices plummeted back to the 130’s. Many investors lost a bundle, but the two schemers got out mostly unscathed.

The whole affair became famously known as “Black Friday.”

When Black Friday comes

I’m gonna stake my claim

I guess I’ll change my name

In 1975, Steely Dan, the rock group consisting of multi-instrumentalist Walter Becker and singer Donald Fagen, wrote a song about it. “Black Friday” was released that same year on their “Katy Lied” album. It was the first single off the album and reached #37 on the Billboard charts.

The song is about the 1869 Gould/Fisk takeover but confuses some listeners due to it’s reference to an Australian town named Muswellbrooke (“Fly down to Muswellbrook”) and the line about kangaroos (“Nothing to do but feed all the kangaroos”).

Fagen later confirmed in an interview the town name was added by chance: “I think we had a map and put our finger down at the place that we thought would be the furthest away from New York or wherever we were at the time. That was it.”

Today the term “Black Friday” is referenced in relation to the Friday after Thanksgiving, traditionally the busiest shopping season of the year and the day retailers go “in the black,” so to speak.

Steely Dan had none of that in mind when they wrote the song.

(“Black Friday” written by Donald Jay Fagen, Walter Carl Becker • Copyright © Universal Music Publishing Group)

Raymond Weeks, the ‘Father of Veterans Day’

By Ken Zurski

In 1945, after serving in the Navy in World War II, Raymond Weeks returned to his family in Birmingham, Alabama and envisioned a national holiday that would honor war veterans. He picked a day, November 11, a date traditionally designated as Armistice Day marking the end of World War I on the “the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of the year.”

Weeks felt the day should be set aside to honor all veterans of all wars.

So the next year he wrote a letter and personally delivered his petition for a “National Veterans Day 1947” to then Army Chief of Staff, General Dwight Eisenhower.

Because of Weeks’ unrelenting commitment to honor those who bravely served the United States during times of war, the first “Veterans Day” event was held on November 11th 1947 in Birmingham.

In 1954, President Eisenhower officially changed the designation of Armistice Day when he signed a bill which made Veterans Day, November 11th, a federal holiday. The bill was proposed by U.S. Representative Edward Rees of Kansas.

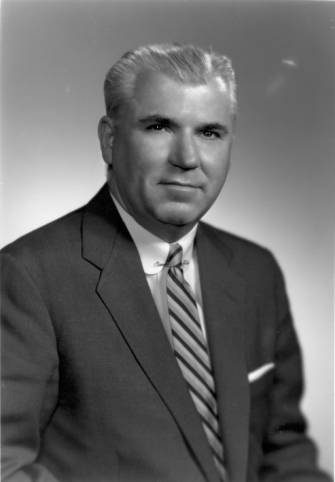

For 38 years after that, Weeks, dubbed the “Father of Veterans Day,” served his hometown of Birmingham as Director of the National Veterans Day Celebration.

Then on November 11, 1982, President Ronald Reagan presented Weeks with the Presidential Citizens Medal.

The President described Weeks as a person who “…devoted his life to serving others, his community, the American veteran, and his nation.”

He added: “So let us go forth from here, having learned the lessons of history, confident in the strength of our system, and anxious to pursue every avenue toward peace. And on this Veterans Day, we will remember and be firm in our commitment to peace, and those who died in defense of our freedom will not have died in vain.”

Weeks died on May 6, 1985 at the age of 76.

(Source: Some text reprinted from Uncompromising Comittment; www.reaganlibrary.archives.gov)

How the Civil War Changed Baseball Forever

By Ken Zurski

Conventional wisdom would suggest that the start of the Civil War in 1861 slowed down the progress of a game like baseball, a sport that was gaining popularity in the years before the conflict began.

And that is true, to a point.

Inevitably as men heeded the call to serve, there just weren’t as many players to take the field. But there were reserves to take their place, especially in the well populated state like New York, which holds the distinction of introducing the world to Base Ball (then written as two words).

While bat-and-ball type games were popping up throughout the country, in New York, an actual team called the Knickerbockers emerged in the 1840’s. While not trailblazers in creating the game, they can be considered pioneers when it comes to the sport. The Knickerbockers actually made and followed rules.

Other teams formed and crowds grew.

Then came the war.

Although pick-up games continued, the sport shifted to the battlefront instead. “Each regiment had its share of disease and desertion; each had it’s ball-players turned soldiers,” remembered George T Stevens, of the 77th Regiment, New York Volunteers.

Union soldiers would play a good “game of nines” to help pass the time.

Otto Boetticher was a Union prisoner at Salisbury, North Carolina. In 1861, at the age of 45, he enlisted in the 68th New York Volunteers and left his job as a commercial artist. The following year he was captured and ended up in Salisbury before a prisoner swap set him free a few months later. Before leaving, Boetticher did a drawing of a prisoner game of baseball.

Boetticher’s drawing, released in 1864, was hardly representative of prison camp descriptions at the time. “Despite the bleak realities of imprisonment,there is a sense of ease and contentment in the image, conveyed in part by pleasures of the game, the glowing sky and sunlight, and the well-ordered composition,” one assessment of the drawing goes.

Boettchler’s lighthearted look at prisoner life wasn’t his fault. The harsh reality of the POW camps would come later with the woeful Libby and Andersonville among others where the prisoner population grew by thousands and unsanitary and overcrowded conditions led to widespread starvation and sickness. Early on, however, the captured soldiers waited for their name to be called.

Why not play a spirited game of baseball?

Boetticher’s print may have been from a July 4th game, when prisoners were allowed to celebrate the nation’s holiday, as one prisoner described, with “music, sack and foot races and baseball.” But if weather permitted and “for those who like it and are able,” baseball was played everyday.

Some might think Boetticher’s depiction of prison life is more deception than reality. But prisoner recollections support the claim that despite the animosity between them, a game of baseball was good fun for both sides.

“I have never seen more smiles today on their oblong faces,” William Crosley a Union sergeant in Company C wrote describing Confederate captors watching a match at Salisbury. “For they have been the most doleful looking set of men I ever saw.”

Once the conflict was over, the game itself was in for an overhaul. Many of the older players who went off to war, were either injured, weary, or worse. That’s when younger players joined in. Skills improved, rules were implemented and the game became more about the playing and the winning rather than just a friendly “game of nines”

Base ball became Baseball – a legitimate competitive sport.

Play ball!