History

Robert Crowe: The Lawyer Behind Chicago’s Infamous Trials

By Ken Zurski

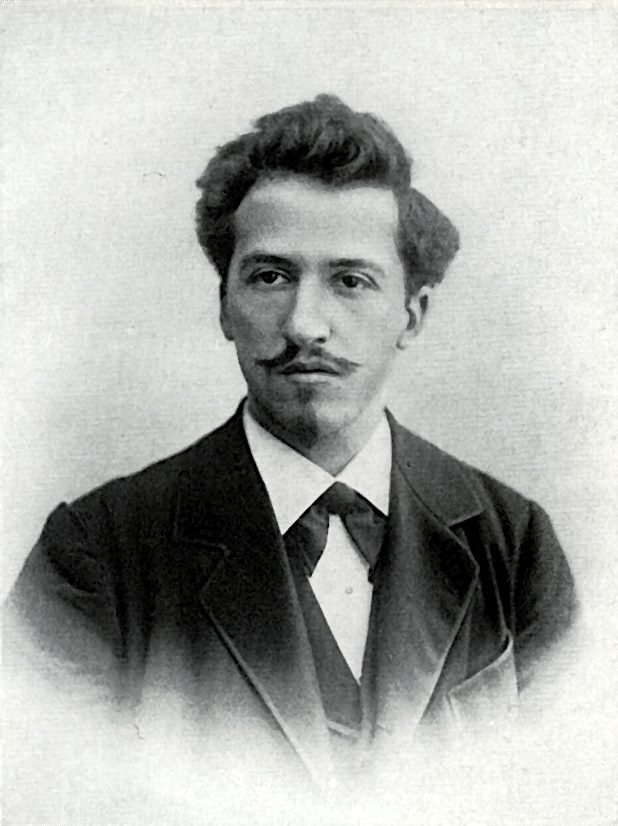

Robert Emmitt Crowe was born in Peoria, Illinois on January 22, 1879, the last of eight children to Patrick and Annie Crowe, Irish immigrants who came to America in the mid-1800s. The large Crowe clan would only know Peoria for a short time. Before he was of school age, his father, a gas lamp lighter for the city, moved the family to Chicago, where Robert would begin a career in law.

Soon Robert Crowe would become the city’s top prosecutor, known today for a classic showdown with famed Chicago defense attorney Clarence Darrow.

There are no books written specifically about Robert Crowe, but there are plenty about Darrow. The authors of these books do not diminish Crowe’s role as Darrow’s antagonist, nor his short upbringing in Peoria—which, as it turns out, was a tumultuous one for the Crowe family.

The Investigative Imagination

During the Irish potato famine of the 1840s, Patrick Crowe emigrated to the U.S., as did many others from the County Galway region. Crowe carried a grudge against the British government and soon joined a group of Irish nationalists known as the Fenian Brotherhood, whose goal was to free Ireland from British rule.

Bombs went off in London and other key British cities. Then on May 6, 1882, a British royal named Lord Frederick Cavendish and his under-secretary were ambushed and gunned down in a Dublin park. The assassination was tied to radical Irish groups both in Europe and abroad. Soon, the investigation reached America.

Fenian chapters were active in cities like Peoria, where Crowe was a member. Shortly after the British bombings, a zealous group of reporters saw Crowe carrying a tin can on his rounds lighting the lamps. “Suppose that can in his hand was really a bomb to be thrown at the King of England?” they speculated. They became convinced (possibly influenced by alcohol, as one report goes) that Crowe was behind the bombings—and possibly the assassination, too. As the Peoriana notebook put it years later: “The imagination of the news hounds began working.”

A wire story was sent out, and Crowe became international news. “Dynamite Crowe” became his moniker in the headlines. Even detectives from Scotland Yard arrived in Peoria to follow his every move.

Crowe never shied away from his hatred of British policies and even fueled speculation by bragging about Fenian-financed, dynamite-making factories in Peoria and New York. In the end, his reported arrest in Peoria by the U.S. Marshall was fabricated, and the “hoax,” as it would be called, dropped out of the news. But it’s the reason Patrick Crowe left Peoria.

A Crime in Chicago

To the Clan na Gael—the Irish activist group which replaced the Fenian Brotherhood—Crowe was a hero, and they invited him to Chicago. The family moved from Peoria to Chicago’s 19th Ward, a poor neighborhood made up of mostly Irish immigrants.

Robert was only three at the time. He attended Chicago public schools, graduated high school and studied law at Yale University. In 1903, he returned to Chicago and opened a private practice, and his political aspirations eventually led to an appointment on the bench as a criminal court judge.

Described as “jut jawed and thin-lipped, with a steady gaze and intimidating manner,” Crowe was elected Cook County state’s attorney in 1920. Fighting corruption, even in government, was the key to his victory. “The real reason for his failure,” Crowe said of his opponent that year, “is that he is guilty and knows it.”

Crowe is best remembered as the prosecutor in the May 1924 murder trial of 14-year-old Bobby Franks. Two University of Chicago students named Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb—both 19 and from wealthy families—were arrested and charged with the crime. They confessed to abducting Franks, killing the boy and dumping the body in a forest preserve. Clarence Darrow, who had a reputation for defending the defenseless, was hired to take on the case. “It never occurred to me that I would refuse to defend anyone,” he once said.

By admitting they had killed Franks “for the thrill of it,” Leopold and Loeb were guilty… but of what punishment? The city was captivated by the senseless murder and subsequent trial. For a full month, they followed every word.

Crowe, who had a reputation for being tough on crime, pushed for the death penalty, but Darrow pushed back. He believed capital punishment did nothing to prevent crimes like these. Impulse, not fear, Darrow argued, guided violent tendencies. But a frustrated Crowe would have none of it. “The only useful thing that remains for them now is to go out of this life and to go out of it as quickly as possible,” he demanded.

Darrow would win the argument. Leopold and Loeb’s lives were spared, and both received life imprisonment sentences instead.

Crowe was left to ponder whether the outcome was “a repudiation of his hang ‘em high brand of justice,” as one author put it.

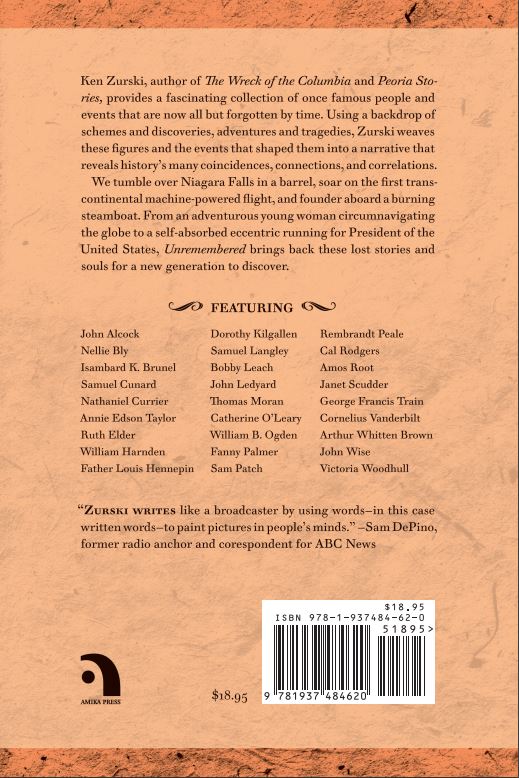

13,000 Words. The Gettysburg Speech before Lincoln’s Address

“Senator Edward Everett had spent his life preparing for this moment,” wrote historian Ted Widmar in “The Other Gettysburg Address.” “If anyone could put the battle into a broad historical context, it was he. His immense erudition and his reputation as a speaker set expectations very high for the address to come.”

Indeed, as Widmar implied, Everett knew the moment was an important one for the country. He was on the battlefield of Gettysburg, now a makeshift graveyard, soon to be the nation’s first national cemetery.

It was November 19, 1863.

He began: “Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature. But the duty to which you have called me must be performed;–grant me, I pray you, your indulgence and your sympathy.

Two hours and 13,000 words later he was done: “I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country there will be no brighter page than that which relates the battles of Gettysburg.”

Widmar wrote: “As it turned out, Americans were correct to assume that history would forever remember the words spoken on that day. But they were not to be his. As we all know, another speaker stole the limelight, and what we now call the Gettysburg Address was close to the opposite of what Everett prepared.

Lincoln spoke: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal….”

When Lincoln ended, it was hardly an address. “Simply the musings of a speaker with no command of Greek history, no polish on the stage, and barely a speech at all – a mere exhalation of around 270 words,” Widmar explained.

It was over in just two minutes.

“Everett’s first sentence, just clearing his throat, was 19 percent of that – 52 words,” Widmar remarked.

The next day , Everett sent Lincoln a note: “Permit me also to express my great admiration of the thoughts expressed by you, with such eloquent simplicity & appropriateness, at the consecration of the Cemetery. I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” he wrote.

The Eccentric Speech That Forecasted the Great Chicago Fire

By Ken Zurski

On October 7, 1871, George Francis Train a businessman and self-proclaimed inventor, spoke in front of a large audience at a lecture hall in Chicago.

Train had just returned from traveling around the world in 80 days (later claiming to be the inspiration for Jules Verne’s fictional character Phileas Fogg) and was on a speaking tour to support a run for President of the United States or as he called it “Dictator of the USA.”

But in Chicago, he delivered a stunning speech. “This is the last public address that will be delivered within these walls.” He told the crowd. “A terrible calamity is impending over the City of Chicago.”

Train’s reputation as an eccentric preceded him. While alarming, his prophesying was quickly forgotten. The next day however, a fire broke out that devastated the city.

The Chicago Times was first to report Train’s speech claiming he was part of a fringe group based in Paris, with off-shoot chapters throughout the world, including Chicago. The article asserted the group, Societe Internationale, could not accomplish what they desired – labor unity- by peaceful means and that the “burning of Chicago” was suggested. The other newspaper in town, the Chicago Evening Journal, debunked such claims and blasted the Times for concocting a communist plot against the city.

Train, however, had some explaining to do. He did by claiming his doomsday prediction was actually in response to shifty government policies that left a crowded, neglected city and its infrastructure prone to a disaster – either by flood or fire. The timing, he said, was purely coincidental.

As for the cause of the blaze, the papers soon found another scapegoat – and a sensationalist story to boot – in a diary cow, a lantern and the unsuspecting wife of a saloon owner named Patrick O’Leary.

The 1970’s Space Movie That Helped Shape a Conspiracy

By Ken Zurski

In 1976, a controversial new book was released that contended the Apollo 11 moon mission never happened. We Never Went to the Moon: America’s Thirty Million Dollar Swindle was written by Bill Kaysing, a Navy midshipman and rocket specialist, who claimed to have inside knowledge of a government conspiracy to fake the moon landing.

Kaysing believes NASA couldn’t safely put a man on the moon by the end of the 1960’s (a promise made by President Kennedy) so they staged it instead. Kaysing’s theories were technical and persuasive and soon a movement of nonbelievers, inspired by the book, was born.

Whether you believed Kaysing or not was a moot point for American screenwriter and director Peter Hyams. A former TV news anchor, Hyams was more interested in how such a thing could actually be pulled off?

“I grew up in the generation where my parents basically believed if it was in the newspaper it was true,” Hyams said in an interview with a film trade magazine. For him, he admits, it was the same with television. “I wondered what would happen if someone faked a whole story.”

So he wrote a story based on the concept.

That was in 1972, four years before Kaysing’s book was released. Hyams shopped the script around but got no takers. Then something unexpected happened. Watergate broke and America was thrown into a government scandal at its highest levels. Interest in a story like a fake moon landing (in the movie’s case, the first manned mission to Mars) had appeal. In 1976, Hyams was given the green light to make his movie as part of deal with ITC Entertainment to produce films with a conspiracy bent.

“Capricorn One” was released in the Summer of 1977. “Would you be shocked to find out the greatest moment of our recent history may not have happened at all?” the movie posters read.

Reviews were mixed. Chicago Tribune film critic Gene Siskel called it “a surprisingly good thriller” while another critic Harry Themal said it was a “somewhat feeble effort at an adventure film.” Variety was even less complimentary calling it “underdeveloped” and the cast “scattershot.”

In the movie, Sam Waterston, James Brolin and O.J. Simpson play the three astronauts. Elliott Gould, Hal Holbrook, Telly Savalas, Brenda Vaccaro and Karen Black round out the cast. While Brolin was known mostly for his television role as Dr, Steven Kiley on Marcus Welby, M.D. Simpson was a celebrity athlete whose acting career was just beginning.

In hindsight the cast was impressive, but the actors weren’t as important as the story.

After the landing is staged and broadcast as real, the nation is told the three astronauts died instantly in a failed reentry. But Gould, as journalist Robert Caulfield, is suspicious. The astronauts, who are harbored, realize they have no recourse but to escape or be killed. “If we go along with you and lie our asses off, the world of truth and ideals is, er, protected,” say’s Waterston’s Lt Col. Peter Willis. “But if we don’t want to take part in some giant rip-off of yours then somehow or other we’re managing to ruin the country.”

From there its a cat and mouse game between the good guys and bad. A dramatic helicopter chase scene ensues. In the end, Caulfield with the help from Brolin’s character exposes the conspiracy.

The movie’s tag-line accentuated the drama:

The mission was a sham. The murders were real.

“In a successful movie, the audience, almost before they see it, know they’re going to like it,” remarked Hyams. “I remember standing in the back of the theater and crying because I knew that something had changed in my life.”

The film’s final chase scenes were pure escapism. “People were clapping and cheering at the end,” Brolin relayed to a reporter shortly after the film’s release.

Today, the film’s legacy may be in the conspiracy only. It’s impact may also have been diminished by the negative attitudes towards O.J. Simpson who in 1994 was charged and acquitted in the brutal murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown.

Even Hyams concedes to his own bizarre trivia: “I’ve made films with two leading men who were subsequently tried for the first degree murder of their wives,” he said referring to Simpson in Capricorn One and Robert Blake in his first film Busting (1974).

Fifty years later, on the 2019 anniversary date of July 20, 1969, the moon landing is still celebrated as one of man’s greatest achievements. “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard,” President Kennedy prophetically said in 1962.

For some, apparently, that was just too hard to believe.

Several years after it happened, a movie showed how it could be done…Hollywood style.

The Poll That Picked FDR To Lose

By Ken Zurski

In 1920, starting with the election of President Warren G. Harding, a weekly magazine called The Literary Digest correctly picked the winner of each subsequent presidential election up to and including Franklin D. Roosevelt’s decisive victory over Herbert Hoover in 1932.

The Literary Digest, founded by two Lutheran ministers in 1890, culled articles from other publications and provided readers with insightful analysis and opinions on the day’s events. Eventually, as the subscriber list grew, the magazine created its own response-based surveys, or polling, as it is known today.

The presidential races were the perfect example of this system working.

So in 1936, with a subscriber base of 10 million and a solid track record, the Digest was ready to declare the next president: “Once again, [we are] asking more than ten million voters — one out of four, representing every county in the United States — to settle November’s election in October,” they bragged.

When the tallies were in, the Digest polls showed Republican Alfred Landon beating incumbent Roosevelt 57-percent to 43-percent. This was a surprise to many who thought Landon didn’t stand a chance.

He didn’t.

Roosevelt was a progressive Democrat whose New Deal policies, like the Social Security Act and Public Pension Act, passed through Congress with mostly bipartisan support. Soon, millions of Americans burdened by the Great Depression would receive federal assistance.

Landon, a moderate, admired Roosevelt but felt he was soft on business and yielded too much presidential power. “I will not promise the moon,” he exclaimed during a campaign speech and warned against raising payroll taxes to pay for benefits. It didn’t work. Roosevelt won all but two states, Maine and Vermont, and sailed to a second term with 60-percent of the popular vote. Even Landon’s hometown state of Kansas, where he had been Governor since 1933, went with the President. In the end, Landon’s 8 electoral votes to Roosevelt’s 532 – or 98-percent – made it the most lopsided general election in history.

In hindsight, poor sampling was blamed for the Digest’s erroneous choice. Not only were subscribers mostly middle to upper class, but only a little over two of the ten million samples were returned, skewing the result.

The big winner, however, besides Roosevelt, was George Gallup, the son of an Iowa dairy farmer and eventual newspaperman, whose upstart polling company American Institute of Public Opinion correctly chose the President over Landon to within 1 percent of the actual margin of victory.

In 1948, the validity of public opinion polls would be questioned again when Gallup incorrectly picked Thomas Dewey to beat Roosevelt’s successor by death, Harry S.Truman.

Since it was widely considered Truman would lose his reelection bid to a full term, Gallup survived the scrutiny.

Even the Chicago Tribune got it wrong, claiming a Dewey presidency was “inevitable,” and printing an early edition with the now infamous headline of “Dewey Defeats Truman.” A humiliation that Truman mocked the next day.

The Literary Digest, however, had no say in the matter.

After the embarrassment In 1938, the magazine merged with another review publication and stopped polling subscribers.

‘Private Snafu,’ the U.S. Army’s Unbecoming Soldier

By Ken Zurski

Beginning in 1943, U.S. Army recruits serving in World War II were introduced to a cartoon character named Private Snafu, a rubbery-faced simpleton with a knack for trouble that one writer described as “a model of everything that a model soldier isn’t.”

The cartoon was the mastermind of movie director Frank Capra, head of the Motion Picture Unit of the U.S. Armed Forces at the time, which produced highly stylized propaganda and training films that starred top Hollywood actors like Clark Gable and Ronald Reagan.

But by far the most popular attraction, especially among the rank-n-file, was the bumbling Snafu. Designed to teach proper etiquette in the Army, the Snafu cartoons turned the tables on military protocol by humorously showing what not to do as a soldier.

Capra originally rejected a contract offer from Walt Disney who reportedly wanted merchandise rights and chose Warner Brothers studios instead to make the films and animator Chuck Jones to produce it.

Although it was clearly ridiculous, Snafu seemed oblivious, therefore making the point that a lack of concentration and absentmindedness can often lead to unwanted – oftentimes deadly – consequences.

The shorts, all about 10 minutes long, were exclusively the Army’s and not subject to standard motion picture codes. So Jones and his writers, including Theodore Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, were limitless in content, although they kept it mostly educational and entertaining at first. In Spies, for example, Snafu forgets to take his malaria medication and gets it in the end – quite literally – by a pesky mosquito.

But that’s only part of the lesson. Snafu, who talks in rhymes, is seen on a pay phone: “Hello Mom, I’ve got a secret, I can only drop a tip. Don’t breathe a word to no one, but I’m going on a trip.” Eavesdropping nearby are the so-called “spies” in the short.

Soon an unsuspecting Snafu is blabbering his secret to anyone within earshot.

Most of the shorts end with Snafu being killed by his own stupidity. Later as the war neared an end, the shorts got edgier and Snafu got smarter. Even the content became racier, with scantily clad girls with body parts cleverly disguised.

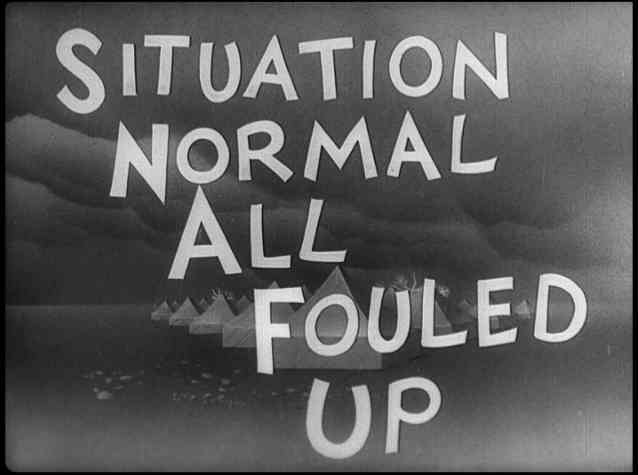

About the only restraint remained in the explanation of the acronym, an unofficial military term: “Situation Normal All Fouled Up.”

‘The Greatest Gift’ is a Story You Know Well

By Ken Zurski

In November 1939 Philip Van Doren Stern, an American author, editor and Civil War historian wrote an original story titled “The Greatest Gift,” a heartwarming Christmas tale about a man named George Pratt who gets a dying wish granted by a guardian angel that literally changes his life.

Stern’s story begins at an iron bridge as a despondent George leans over the rail:

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” a quiet voice beside him

said.George turned resentfully to a little man he had never seen

before. He was stout, well past middle age, and his round

cheeks were pink in the winter air as though they had just been

shaved. “Wouldn’t do what?” George asked sullenly.

“What you were thinking of doing.”

“How do you know what I was thinking?”

“Oh, we make it our business to know a lot of things,” the

stranger said easily.

Stern desperately tried to get his little story published, but it never sold. So in 1943, he made it into a Christmas card book and mailed 200 copies to family and friends.

The card book and story somehow caught the attention of RKO Pictures producer David Hempstead who showed it to actor Cary Grant’s agent. In April 1944, RKO bought the rights but failed to create a satisfactory script. Grant went on to make “The Bishop’s Wife.”

However, another acclaimed Hollywood heavyweight, Frank Capra, who already had three Best Directing Oscars to his name, liked the idea. RKO was happy to unload the rights. “The story itself is slight, in the sense, it’s short,” Capri said referring to Stern’s book. “But not slight in content.”

Capra bought it and brought in a slew of writers to polish the story. They hired another a well-known actor James Stewart to play the main character renamed George Bailey and in December of 1946, “It’s a Wonderful Life” was released in theaters.

Winston Churchill, The Boers War and the Invasion of the ‘Body Snatchers’

By Ken Zurski

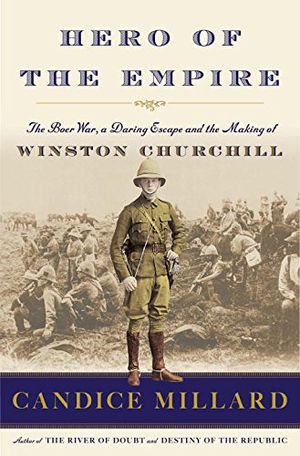

In the book Hero of the Empire, author Candice Millard explores the military service of a young Winston Churchill and the future Prime Minister of England’s exploits in the Boers War, a devastating conflict against the fiercely independent South African Republic of Transvall, or Boers, that’s as much a part of British history as the two subsequent World Wars.

In 1899, Churchill was in his twenties and officially not a soldier, but a correspondent for the Morning Post. However, he bravely and willingly fought alongside his fellow countrymen. As Millard captures vividly in her book, when a British armored train was ambushed, Churchill fought back, was captured, imprisoned, managed to escape, and traversed hundreds of miles of enemy territory to freedom. He then returned and resumed his duties in the war. Millard’s expert narrative paints the young Churchill as a man of great strength, determination and steadfast loyalty.

The same attributes can also be applied to another famous figure in history who did not fight like Churchill, but bravely dodged the bullets of the Boers to do a thankless and daring task. His contribution is touched on briefly in the book, but is worth noting here as an example of a man whose legacy of peace and non-violence includes the brutal reality of warfare.

In stark contrast to Churchill’s call to arms, this figure refused to pick up a weapon or engage in hand to hand combat. His Hindu faith prevented that, but his desire for justice could not be suppressed. He was an Indian-born lawyer in a country under the flag of the British Empire who went to South Africa to defend his people from cruelty imposed by the Boers. When war broke out, he wanted to contribute, along with other persecuted Hindu followers.

But how?

So he asked the British government if he could put together a team of men to perform the incessant task of removing bodies, dead or wounded, from the heat of battle. The government approved the request, but made it clear that the men were under no obligation or safeguards from the British Army. The decision to risk their own lives in order to save others was theirs and theirs alone.

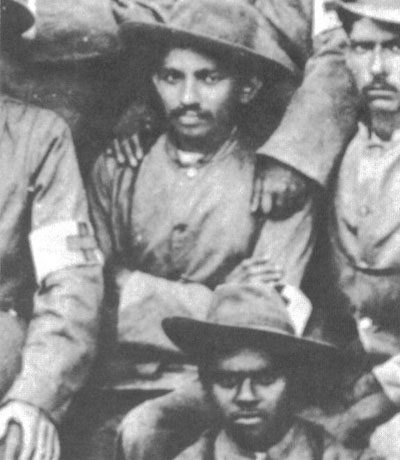

“Body snatchers,” was the term used by British troops to describe the men who retrieved “not just bodies from the battlefield, they hoped, but young men from the jaws of death,” Millard writes. The “body snatchers” wore wide brim hats and simple loose fitting khaki uniforms and were distinguished by “a white band with a red cross on it wrapped around their left arms.”

Their efforts were lauded by superiors and observers alike. “Anywhere among the shell fire, you could see them kneeling and performing little quick operations that required deftness and steadiness of hand,” wrote John Black Atkins a reporter for the Manchester Guardian.

By now you may discern that the person who assembled this unusual band of brave men is important to history. Millard doesn’t hold anyone in suspense.

The man was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi whose place in history as the influential Indian civil rights leader was just beginning to emerge.

When war broke out, Gandhi, who was 31 at the time, wanted to disprove stereotypes that Hindus were unfit for battlefield service.

“Although his convictions would not allow him to fight,” Millard writes, “he had gathered together more than a thousand men to form a corps of stretcher bearers.”

Later in his autobiography, Gandhi would recall his non-violent role in the Boers War.

“Our humble work was at the moment much praised, and the Indians’ prestige was enhanced,” he wrote.

“We had no hesitation.”

(Sources: Hero of the Empire by Candace Millard; The Story of My Life by M.K. Gandhi)

The Legacy of Perry Como: Christmas Crooner and Family-Friendly Performer

By Ken Zurski

Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television special and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time.

That said he may have been the most misunderstood as well.

Como was a one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced his craft incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week. Even Perry was surprised by the remuneration. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the town’s perceived association with mobsters and legalized prostitution, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduce his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually standing backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many wondered how much of it was real. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for 46 consecutive years ending in 1994, seven years before his death in 2001 at the age of 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)

There Is An Artist Behind The Iconic ‘Partridge Family’ Bus

By Ken Zurski

Painter Piet Mondrian, born in 1872, was an important leader in the development of modern abstract art and a major exponent of the Dutch abstract art movement known as De Stijl (“The Style”).

Mondrian used the simplest combinations of straight lines, right angles, primary colors, and black, white, and gray in his paintings.

According to one art historian: “The resulting works possess an extreme formal purity that embodies the artist’s spiritual belief in a harmonious cosmos.”

Mondrian who died in 1944 probably would never have imagined that his well-known artistic style would be the inspiration for a popular 1970’s television show called “The Partridge Family.”

Mondrian’s apparent contribution to the show was the exterior paint job of a school bus used by the fictional – but conventional – family of traveling musicians and singers. Mondrian’s style was on full display, seemingly based on one of his paintings.

The bus became the family’s trademark.

From Yahoo Answers: “Although the exterior paint job was arguably based on Mondrian’s Composizione 1921, it was never explained in the show why this middle class family from Southern California chose Dutch proto-modernism exterior paint, rather than the traditional school bus yellow.”

“The Partridge Family” ran on ABC television from September 25, 1970, until it ended on March 23, 1974. It would find an appreciate and loyal audience in syndication for years. Apparently the bus wasn’t so fortunate. As the story goes, after the show ended, the bus was sold several times until it was found abandoned in a parking lot at Lucy’s Tacos In East Los Angeles.

It was reportedly junked in 1987.

(Some text reprinted from Britannica.com and other internet sources)

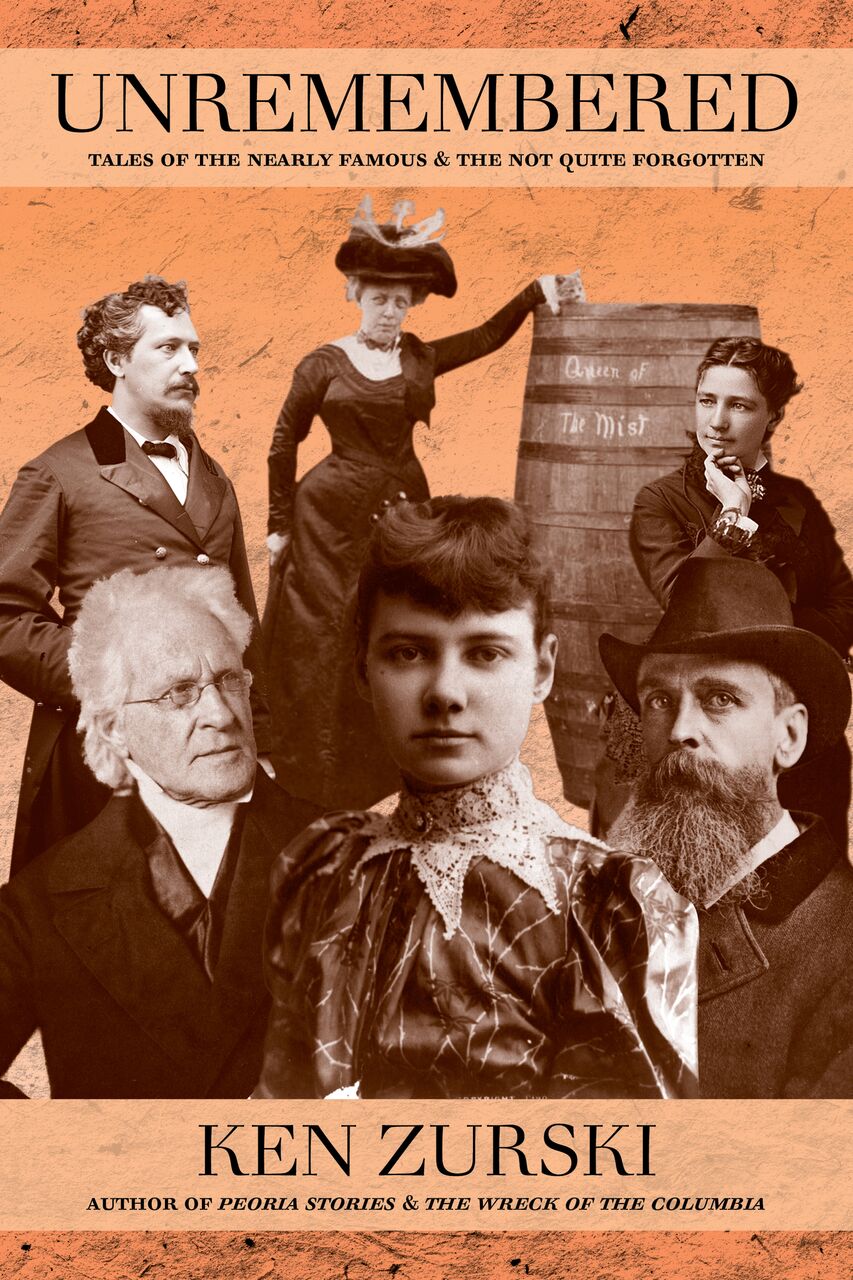

Ken Zurski’s book “Unremembered: Tales of the Nearly Famous and the Not Quite Forgotten is available now http://a.co/d/hemqBno