Ken Zurski

A Brother’s Lamentation

By Ken Zurski

On April 15 1865, the day after President Lincoln was struck down by an assassin’s bullet, Edwin Booth, a popular stage actor in New York, was told his younger brother John had pulled the trigger.

Edwin was appearing in a “successful” show at the time and immediately asked that it shut down. “The news of this morning has made me wretched,” he wrote, “not only because of my brother’s crime, but because a most justly honored and patriotic ruler has fallen.”

Edwin and his brother were estranged. Politics and ideology had separated them, as it did the rest of the country. “When I told John I voted for Lincoln,” Edwin recalled, “he expressed deep regret.”

Edwin feared for his own life after news that another brother, Junius, also an actor, had been threatened by an angry mob in Cincinnati. “Whatever calamity may befall me and mine, my country, one and indivisible, has my warmest devotion,” Edwin explained before going into hiding.

In January the following year, friends urged him to return to the stage. He reluctantly agreed. As his favorite character, Hamlet, Edwin stepped in front of a packed theater.

He was greeted by a tremendous applause.

Ask Your Local Library to Add UNREMEMBERED!

Ask your local library to get it …give the book title and the author. Available on Ingram, Baker & Taylor and Amazon http://a.co/d/iteJoll

Ken Zurski, author of The Wreck of the Columbia and Peoria Stories, provides a fascinating collection of once famous people and events that are now all but forgotten by time. Using a backdrop of schemes and discoveries, adventures and tragedies, Zurski weaves these figures and the events that shaped them into a narrative that reveals history’s many coincidences, connections, and correlations.

We tumble over Niagara Falls in a barrel, soar on the first transcontinental machine-powered flight, and founder aboard a burning steamboat. From an adventurous young woman circumnavigating the globe to a self-absorbed eccentric running for President of the United States, Unremembered brings back these lost stories and souls for a new generation to discover.

John Alcock

Nellie Bly

Isambard K. Brunel

Samuel Cunard

Nathaniel Currier

Annie Edson Taylor

Ruth Elder

William Harnden

Father Louis Hennepin

Dorothy Kilgallen

Samuel Langley

Bobby Leach

John Ledyard

Thomas Moran

Catherine O’Leary

William B. Ogden

Fanny Palmer

Sam Patch

Rembrandt Peale

Cal Rodgers

Amos Root

Janet Scudder

George Francis Train

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Arthur Whitten Brown

John Wise

Victoria Woodhull

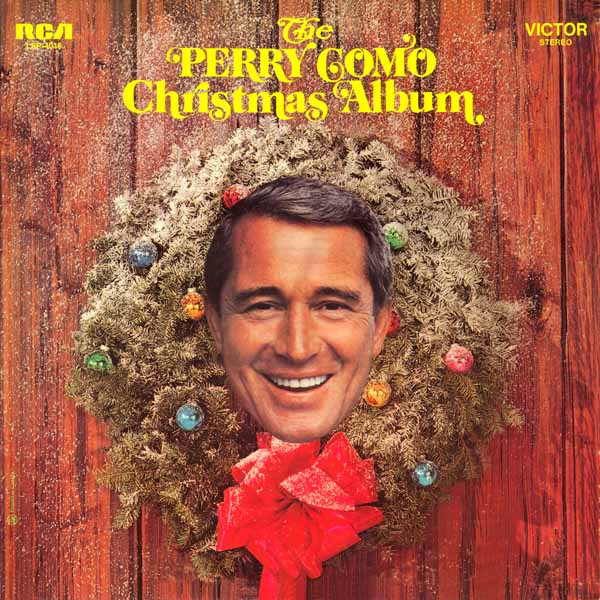

‘Good Guy’ Perry Como was one of the TV Kings of Christmas

By Ken Zurski

Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time. Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television special and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Como’s face and voice became synonymous with the sounds of the season.

That said he may have been the most misunderstood as well.

Como was a one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced his craft incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week. Even Perry was surprised by the remuneration. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the town’s perceived association with mobsters and legalized prostitution, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduce his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually standing backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many wondered how much of it was real. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for 46 consecutive years ending in 1994, seven years before his death in 2001 at the age of 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)

The Year the President Moved Thanksgiving Up a Week

By Ken Zurski

In September of 1939, Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a presidential proclamation to move Thanksgiving one week earlier, to November 23, the fourth Thursday of the month, rather than the traditional last Thursday of the month, where it had been observed since the Civil War.

That year, the last Thursday of November fell on the 30th, the fifth week and final day of the month, and late for the start of the shopping season. The Retail Dry Goods Association, a group that represented merchants who were already reeling from the Great Depression, went to Commerce Secretary Harry Hopkins who went to Roosevelt.

Help the retailers, Hopkins pleaded.

Roosevelt listened. He was trying to fix the economy not break it.

Thanksgiving would be celebrated one week earlier, he announced.

Apparently, the move was within his presidential powers since no precedent on the date was set. Thanksgiving, the day, was not federally mandated and the actual date had been moved before. Many states, however, balked at Roosevelt’s plan. Schools were scheduled off on the original Thanksgiving date and a host of other events like football games, both at the local and college level, would have to be cancelled or moved.

One irate coach threatened to vote “Republican” if Roosevelt interfered with his team’s game. Others at the government level were similarly upset. “Merchants or no merchants, I see no reason for changing it,” chirped an official from the opposing state of Massachusetts.

In contrast, Illinois Governor Henry Horner echoed the sentiments of those who may not have agreed with the president’s switch, but dutifully followed orders.

“I shall issue a formal proclamation fixing the date of Thanksgiving hoping there will be uniformity in the observance of that important day,” he declared, steadfastly in the president’s corner.

Horner was a Democrat and across the country opinions about the change were similarly split down party line: 22 states were for it; 23 against and 3 went with both dates.

In jest, Atlantic City Mayor Thomas Taggart, a Republican, dubbed the early date, “Franksgiving.” Others called it “Roosevelt’s Thanksgiving” or “Roosevelt”s hangover Thanksgiving Day.” More politically, some dubbed it “Democratic Thanksgiving Day” and the following Thursday as “Republican Day.” One observer noted, “This country is so divided it can’t even agree on a day of Thanksgiving.”

In some Midwestern states, especially among farmers, the controversy was irrelevant thanks to a bountiful harvest. “This year the crops certainly justified Thanksgiving, even justified two,” reported the Omaha-World Herald.

Roosevelt made the change official for the succeeding two years ’40 & ’41, since Thursday would fall late in the calendar both times. Then in 1941 The Wall Street Journal released data that showed no change in holiday retail sales when Thanksgiving fell earlier in the month. Roosevelt acknowledged the apparent miscalculation.

However, due to the uproar, later that year, Congress approved a joint resolution making Thanksgiving a federal holiday to be held on the fourth Thursday of the month, regardless of how many weeks were in November.

On December 26, 1941, Roosevelt signed it into law.

General Washington Didn’t Receive the Declaration of Independence until July 8.

By Ken Zurski

On July 8 1776, four days after the Continental Congress passed the Declaration of Independence, a copy was sent to General George Washington who was preparing for battle in New York City.

Washington anxiously awaited word from the assembly in Philadelphia. He knew how important the declaration would be to his troops. Up to that point the New York contingent of the Continental Army, who had been together for nearly a full year, hadn’t fired a single shot yet. They were frustrated, antsy and for the most part continually drunk. The declaration would help boost morale, Washington thought.

Already, talk of such a declaration had been stirring up emotions within the ranks. In May of that year, in words later shaped by Thomas Jefferson, Virginian George Mason drew up a sentence about being “born equally” with “inherent natural rights.” And on June 7, Virginian Richard Henry Lee, introduced a congressional resolution declaring that the United Colonies “ought to be free and independent states.” Even Washington , in the spring of 1776, crafted a statement that supported the idea of independence as an incentive to fight. “My countrymen, I know, from their form of government and steady attachment therefore to royalty, will come reluctantly into the idea of independency,” he wrote.

So on July 9, at six o clock in evening, Washington ordered his troops to gather. He had previewed the contents of the document and included it in his “General’s Orders,” which would be read aloud to the men.

But it came with a caveat. Washington had warned the troops of the consequences that any official documentation of independence would mean if defeated. Treason, he implored, was something the British ruler did not take lightly. Traitors in the past were subject to gruesome disemboweling and beheadings, he explained. Washington himself knew if captured, he would be hanged.

This was literally a fight to the end, he argued.

The men stood with anticipation as the “General’s Orders” were read. Patiently they waited as several paragraphs of typical military reports and directives were announced. One included the procurement of a chaplain assigned to each regiment. “The blessing and protection of Heaven are at all times necessary but especially so in times of public distress and danger,” the missive proclaimed.

Then finally…

“…The Honorable the Continental Congress impelled by the dictates of duty, policy and necessity, having been pleased to dissolve the connection which subsisted between the Country, and Great Britain, and to declare the United Colonies of America, free and independent STATES.”

Upon hearing the words, the men let up “three huzzas” a witness reported. In fact, their enthusiasm led to an act of debauchery that irked Washington. The soldiers marched down Broadway Street and proceeded to topple the large statue of King George III, decapitating it in the process.

Washington was livid. He told the troops that while their “high spirits” was commendable, their behavior was not. The general wanted an army of orderly respectful men, not savages. Even defacing the likeness of the British King was inadmissible in his eyes.

However sanctimonious that may have sounded, Washington must have been pleased that the statue’s 4 ,000 pounds of gilded lead was melted down to make nearly 43-thousand musket bullets.

Washington was also thrilled by his troop’s eagerness to fight. “They [the British] will have to wade through much blood and slaughter before they can carry out any part of our works,” he wrote about the impending conflict.

Then on July 12, several British ships, including the forty-gun Phoenix, cut through a thin American defense and blasted the city. It was a show of force meant to rattle the colonists into submissiveness. It certainly rattled the nerves of Washington’s untested soldiers who were shaken and distressed by the cries of women and children fleeing the blasts. There was little resistance.

Washington later expressed his disappointment. “A weak curiosity at such a time makes a man look mean and contemptible,” he said chastising the troops.

After the embarrassment, British commander William Howe offered Washington clemency for the rebels if the General surrendered. Washington flatly refused.

The following month, it would get worse. Due to more defeats, the rebels were forced to flee New York to Pennsylvania and reorganize. Later that year, in December, Washington would famously cross the icy Delaware River for a surprise attack in Trenton, New Jersey.

The Revolutionary War would continue for another seven years.

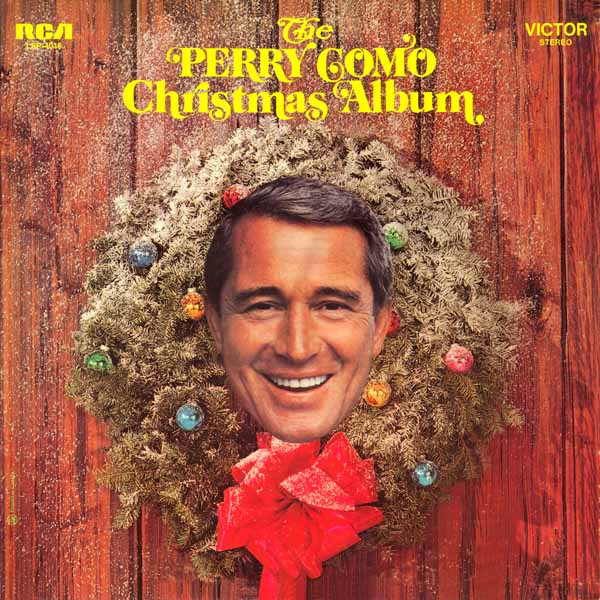

As Christmas Crooners Go, Perry Como Was As ‘Pure As The Driven Snow’

By Ken Zurski

Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time. Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television specials and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Como’s face and voice became synonymous with the sounds of the season.

Today, however, in a more crowded market for Christmas music and numerous more versions of favorite holiday classics (and new ones too) from more contemporary artists in all genres, Como’s versions might get lost in the mix.

But it’s still in there.

That said, as a performer, he may have been misunderstood as well.

Como was considered one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced and rehearsed incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week, admittedly a large sum for a Vegas act at the time. Even Perry was surprised. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the desert town’s reputation of gambling and prostituition, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduced his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament and sleepy manner was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many had to ask if it was real or just an act. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for three decades ending in 1994, seven years before his death from symptoms of Alzheimer’s in 2001. He was 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)