History

The Origins of Father’s Day: A ‘Second Christmas’ for Dads

By Ken Zurski

Nearly every May in the 1930’s, a radio performer named Robert Spere staged rallies in New York City promoting a day set aside not just to honor moms, but dads as well.

His hope was to change “Mother’s Day” to “Parent’s Day” instead.

Spere, a children’s program host known as “Uncle Robert” told his attentive audience: “We should all have love for mom and dad every day, but ‘Parent’s Day’ is a reminder that both parents should be loved and respected together.”

Spere was onto to something, but it would have to wait.

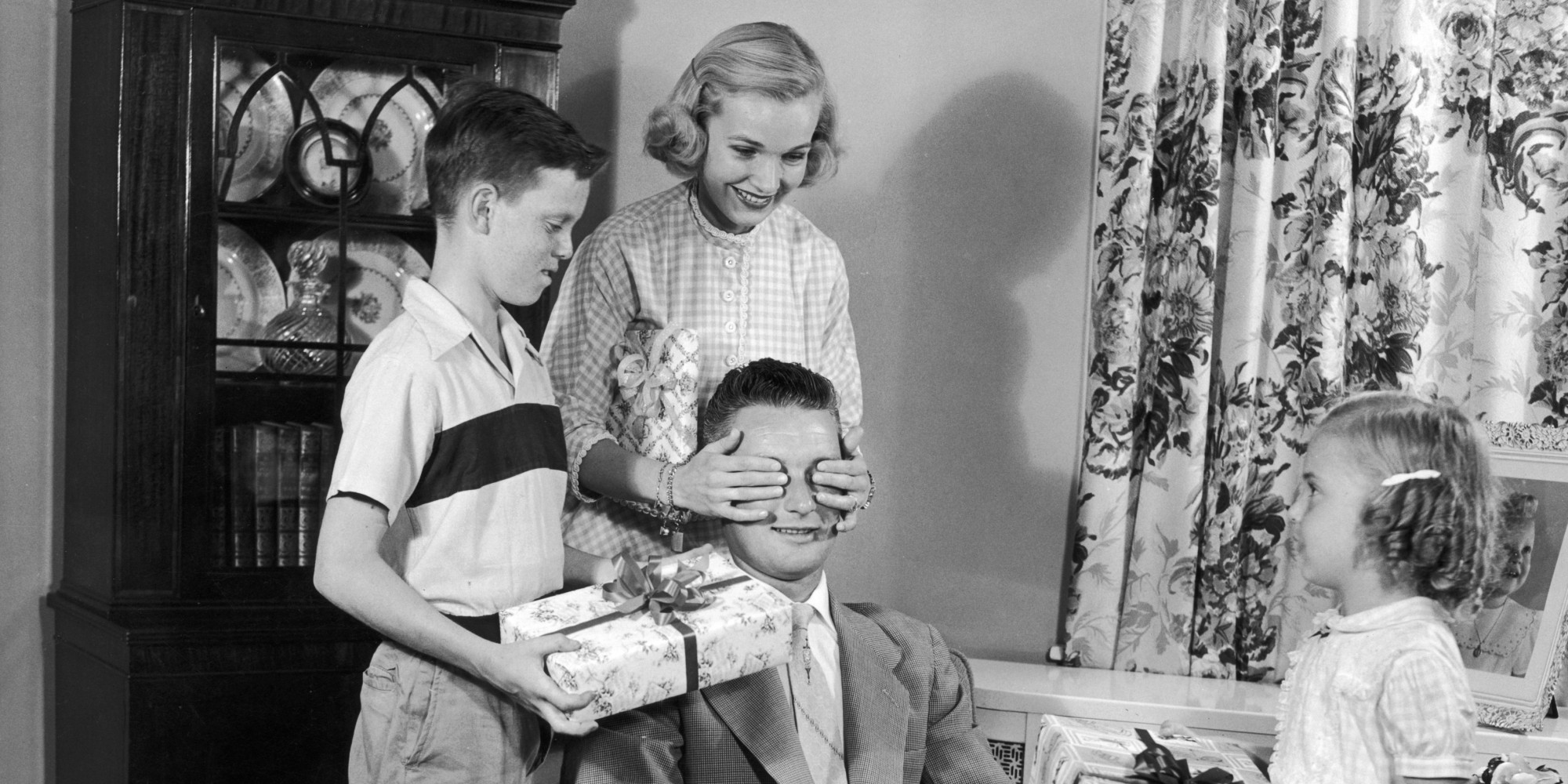

Much earlier, in 1908, a day set aside to celebrate mom, affectionately known as Mother’s Day, became a national day of observance. But there was no enthusiasm for a day set aside for fathers. “Men scoffed at the holiday’s sentimental attempts to domesticate manliness with flowers and gift-giving,” one historian wrote.

Retailers, however, liked the idea. They promoted a “second Christmas” for dads with gifts of tools, neckties and tobacco, instead of flowers and cards. But it never gelled. Even Spere’s “Parent’s Day” idea hit a snag when the Great Depression hit. (Today, “Parents Day” is officially celebrated on the fourth Sunday of every July.)

In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed a proclamation honoring fathers on the third Sunday of June.

Six years later, in 1972, with President Richard Nixon’s signature, “Father’s Day” officially became a national holiday.

John Banvard and the ‘Three-Mile Painting’

By Ken Zurski

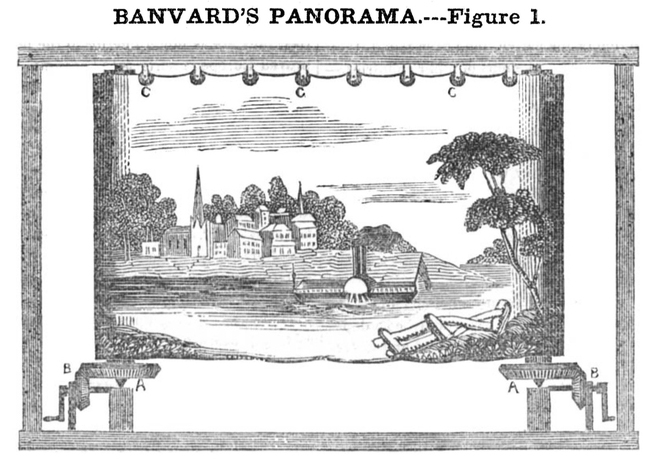

In the 1840’s, artist John Banvard created the largest, longest and most ambitious painting of its time. Figuratively rather than literally, it was named “Three-Mile Painting” because it consisted of a series of large painted scenes in sequence called a “moving panorama.”

Banvard chose the continuous landscape of the Mississippi River as his subject. He spent two years on the river traveling by boat and hunting for food to survive. He sketched hundreds of scenic vistas from St Louis to New Orleans and when finished holed himself up in Louisville, Kentucky to begin rolling and unrolling canvases. He then transferred the sketches at a breakneck pace.

It was as massive an undertaking as the subject itself.

Each panel stood 12 feet high and together stretched for 1300 feet – not quite a quarter of a mile in total. That was far short of the “three miles” Banvard had advertised, but who was counting?

Banvard presented the work to packed houses and appreciative audiences and in 1846, by request, brought the massive painting to England and Queen Victoria for a private showing in Windsor Castle.

Banvard made a fortune and took his success personally. He fought with fellow panorama artists calling them “imitators” and in return they called Banvard ”uncultivated.” When Banvard built a castle-like estate on 60 acres in New York’s Long Island, it was admonished by locals for being overtly excessive, pretentious and impractical. They called it “Banvard’s Folly.” It later became a lavish hotel.

In 1851, in direct competition with Banvard, another panorama depiction of the Mississippi River was presented by artist John L Egan. Although it was advertised as a whopping “15,000 feet” in length, a more factual estimate puts it closer to 348 feet. Each panel was 8- foot high and 14-feet long. The rolled canvas was so large that matinee viewers were treated to a stroll down the river’s stream in the afternoon while in the evening performance, as the canvas was rolled back in reverse, a trip upstream was presented.

While Banvard claimed to be first to showcase the wonders of the mighty river on canvas, Egan’s deception is better known today because its scenes have been saved, making it the last known surviving panorama of its time.

Unfortunately that is not the case with Banvard’s “Three-Mile Painting.” It was never persevered or copied. Because of its size and quantity, the panels were separated and used as scenery backdrops in opera productions.

When the canvases became worn from exposure they were shredded and recycled for insulation in houses.

The First Debacle of Millard Fillmore’s Unexpected Presidency

By Ken Zurski

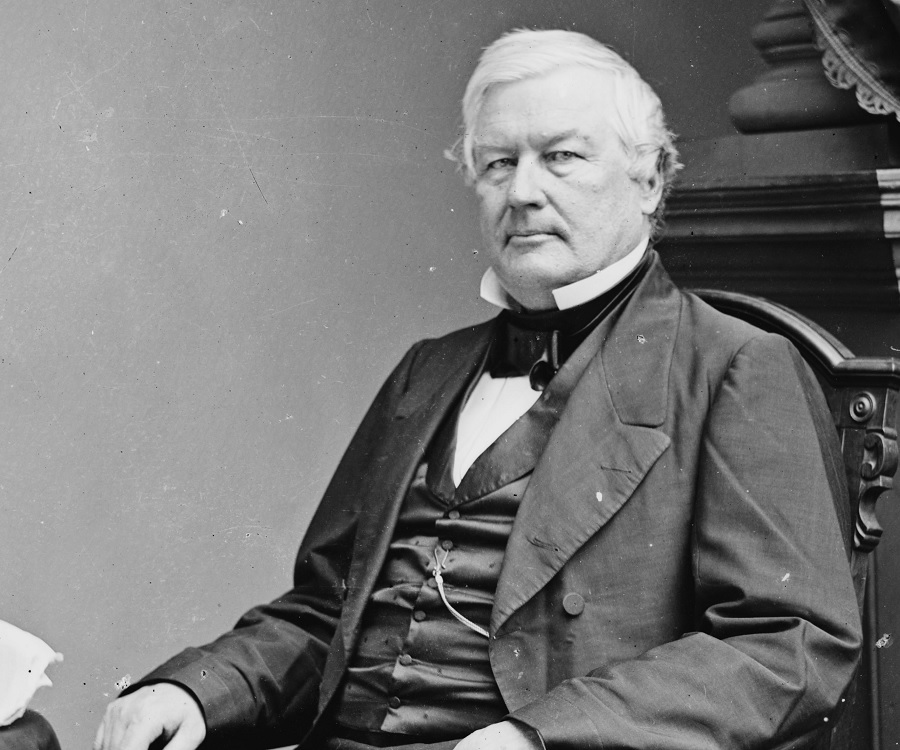

On July 10, 1850, MILLARD FILLMORE unexpectedly became the Thirteenth President of the United States.

No one saw it coming, not the least of which was Fillmore, who had been vice president to Zachery Taylor at the time, a job he sought but ultimately didn’t think he would get.

Even Taylor, a popular military general, had reservations about running for president. But duty called. “If my friends deem it good for the country that I be a candidate,” Taylor obliged. “so be it.” Fillmore, not known as politically savvy or ambitious, was picked as Taylor’s running mate because he was more of a Whig, especially on slavery.

Once in the White House, however, Fillmore had little to do. The job held no great power or influence and only one vice president, John Tyler, had ever assumed the presidency unexpectedly, when the ninth president William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia just 31 days into his term of office.

In similar unexpectedness, just sixteen months into his own presidential term, Taylor was dead.

A bad stomachache and poor medical care did him in. A Stunned Fillmore took the oath of office and set the stage for what is considered to be one of the worst presidencies in history.

An attribution that was set with Fillmore’s first act as president.

As the story goes, immediately after Taylor’s death, the members of his cabinet, in ceremonial unity and respect, turned in resignation letters. They fully expected Fillmore to deny their requests. Their thinking was two-fold. For one, Fillmore was inexperienced. In another sentiment, he surely needed their help. Plus, Fillmore and Taylor were associates, not adversaries. Politically speaking, and in technicality too, they were all on the same team. Whether they personally liked the vice president or not, and most did not, a nation’s stability and Taylor’s legacy was at stake.

Clearly, Fillmore could grasp that, they thought.

They were wrong.

Fillmore accepted their resignation letters and in effect fired them all. But, he asked, could they stay on a month so he could appoint a new team.

Each one refused.

Baseball’s ‘Pastimes’ Played the Game For Fun Only

By Ken Zurski

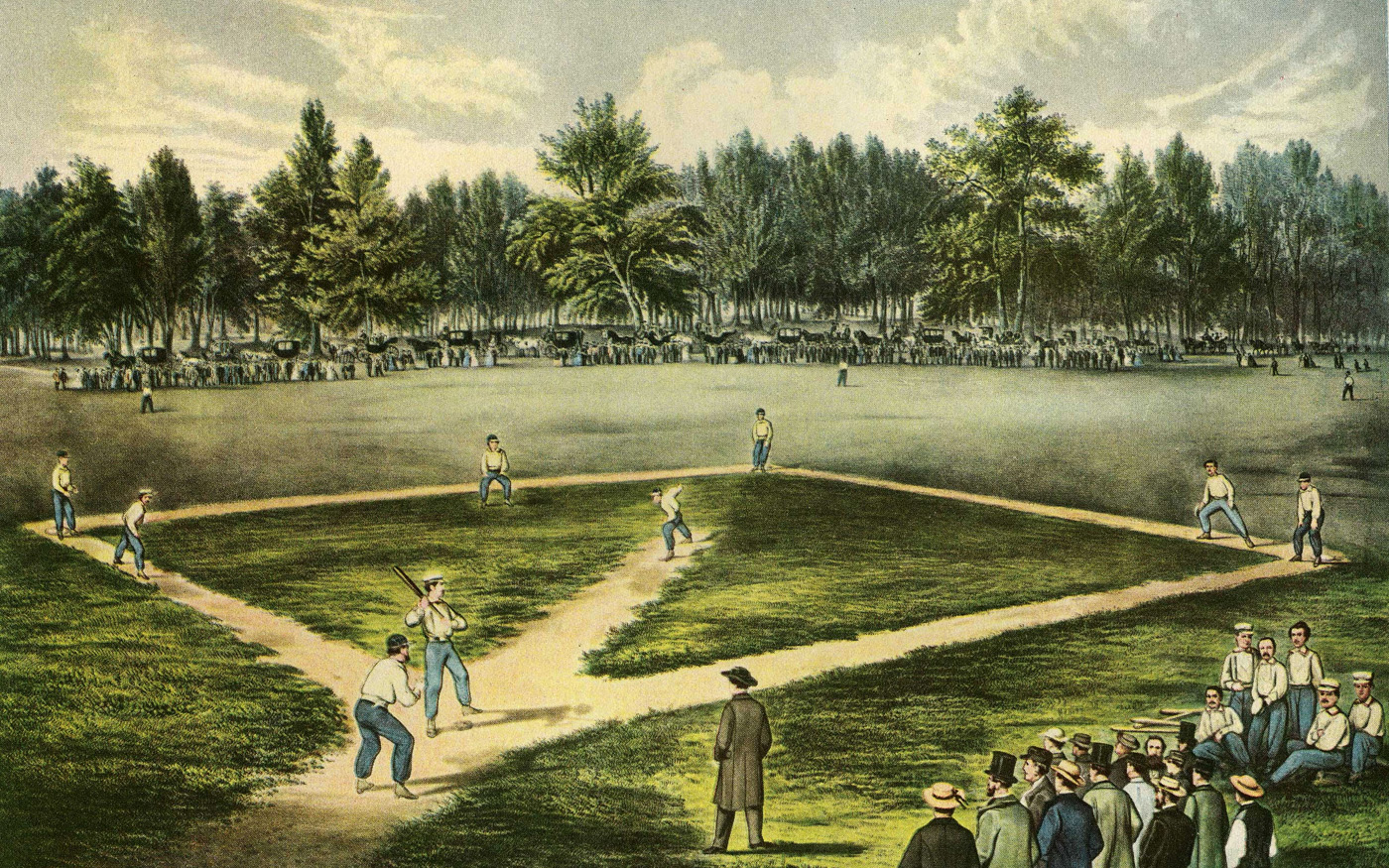

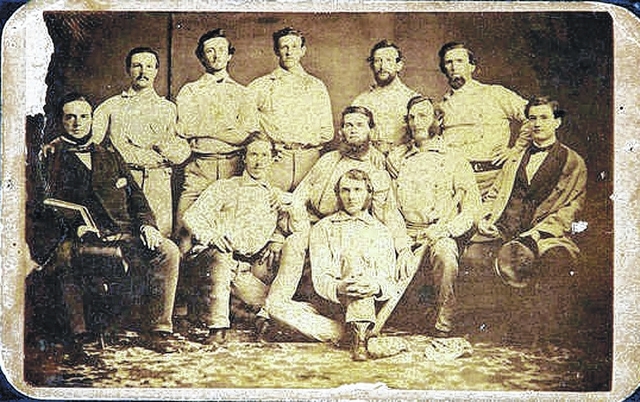

In the heart of Brooklyn, in 1858, a group of men known as the Pastimes, hiked up their wool trousers, buttoned-down their flannel shirts, and ran onto an open grassy field to play a game they fondly referred to as “base ball.”

The team was one of several in the New York area, but the Pastimes were different. Instead of being a ragtag lot of patchwork players, the Pastimes billed themselves as more refined and high-minded. Many of the members were prominent citizens, some even held government jobs. They enjoyed spending the day together, socializing and being seen.

Base ball, the game, they said, was just good exercise.

To signify their self-worth, the Pastimes arrived at away games in carriages and usually in a line. “Like a funeral procession passing,” remarked one observer. You couldn’t help but notice.

After the game they invited their rivals, win or lose, to a fancy spread of food and spirits. Oftentimes this was the reason for getting together in the first place. The game was the appetizer. The day’s highlight however was the feast. The opposing players rarely complained.

Despite the revelry off the field, the Pastimes did actually play the game. But it hardly represented what we know baseball to be today. Pitchers tossed the ball (there was no “throwing” allowed) and strikes were rare. With no called balls, a batter could wait through 30 to 40 tosses or more before deciding to hit it. The batter was out when a fielder caught the ball on a fly or on “a bound.” And player’s running the bases rarely touched them. After all, who was going to make them? “What jolly fellows they were at the time,” wrote Henry Chadwick, a New York journalist and Pastimes supporter, “one and all of them.”

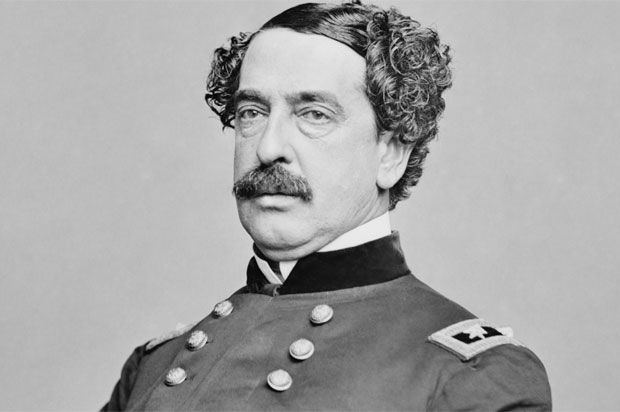

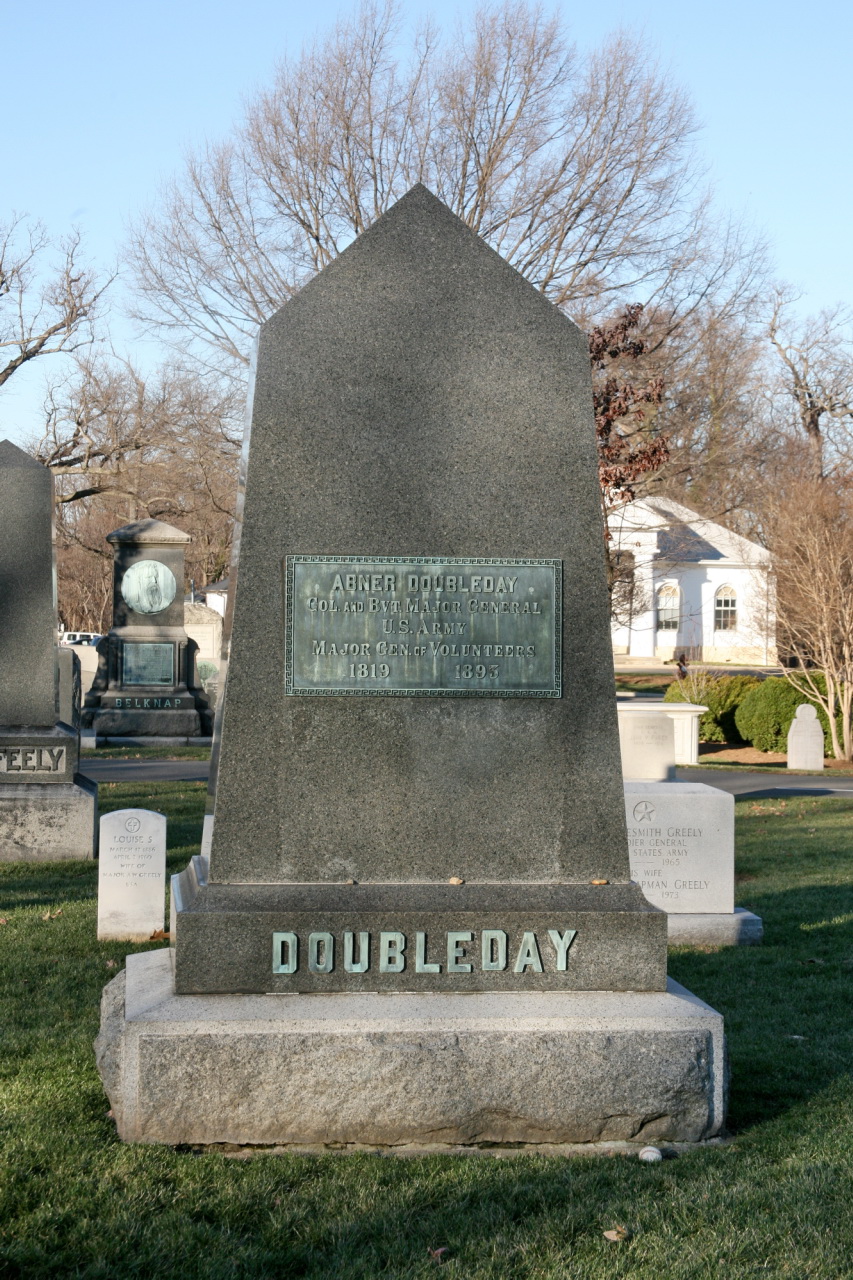

Most of the early history of baseball hails from New York, with Cooperstown, considered to be the place where the game was invented and the current site of the Baseball Hall Of Fame and Museum, as a prime example. While bat-and-ball type games were popping up throughout the country, in New York, an actual team emerged in the 1840’s calling themselves the Knickerbockers. While they’re not trailblazers in creating the game, they can be considered pioneers when it comes to the sport. The Knickerbockers actually made and followed some rules.

The play itself was raw, almost comical, but enjoyable for spectators. “Ball Days” became popular, and the Knickerbockers were fun to watch. Soon other teams would join in, some more determined than others. The Pastimes had their reasons too.

At some point, as more teams participated, the game started changing. It became more challenging and competitive and the Pastimes who had been enjoying a day of friendly raillery – and not much more – had to adjust. “Until the club became ambitious of winning matches and began to sacrifice the original objects of the organization to the desire to strengthen their nine-match playing,” Chadwick wrote, “everything went on swimmingly.” But losing takes its toll. And for the lowly playing Pastimes, the fun went out of the day. “Finally the spirit of the club, having been dampened by repeated defeats at the hands of stronger nines, gave out,” Chadwick grumbled on. “The Pastimes went out of existence.”

Well that and the start of the war too.

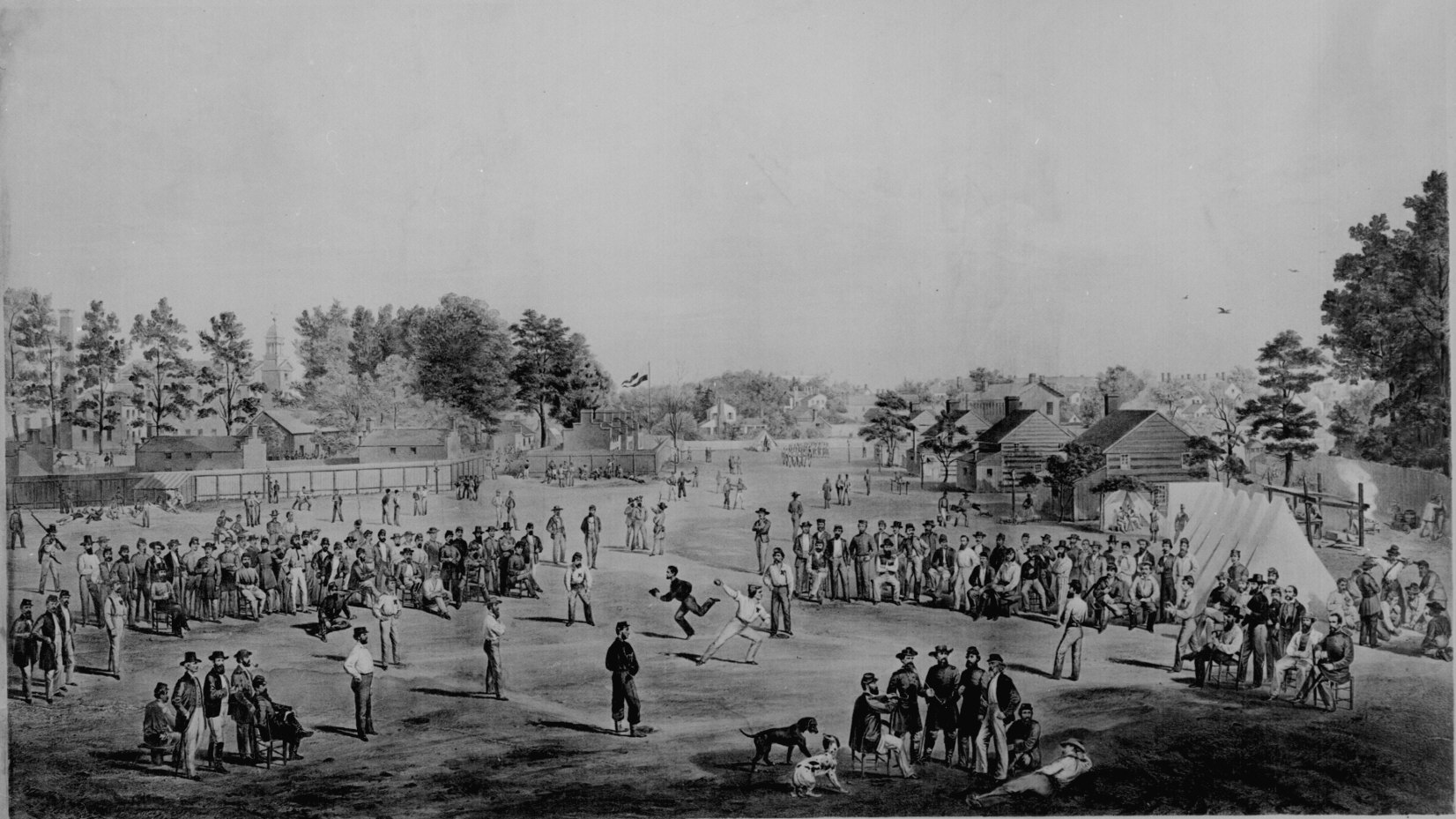

Conventional wisdom would suggest that the Civil War slowed the progress of the game. And that was true, to a point. Inevitably as men marched off to war, there just weren’t enough players to take the field. Many top players did heed the call to serve, but others chose to delay their service and keep playing. Plus there were always reserves, especially in a well populated state like New York. The game carried on, despite the conflict. In fact, it was just as popular for the soldiers who shared a good game of nines to help pass the time. “Each regiment had its share of disease and desertion; each had it’s ball-players turned soldiers,” remembered George T Stevens, of the 77th Regiment, New York Volunteers. Baseball was a game that required an open space, a stick, something to hit, and not much else. Reports of ball games in prison camps were widespread.

Once the conflict was over, the game itself was in for an overhaul. Many of the older players were either injured, weary from the war, or worse. That’s when younger players joined in, skills improved, and rules were implemented.

Base ball became Baseball – a legitimate competitive sport.

The Pastimes would have never fit in.

Perhaps the most appealing part of the early game would have also pleased the more ardent followers of baseball today, especially those who crave the action on the offensive side of the ball. On October 28, 1858, the Pastimes played the Newark Adriatics. According to the rules back then, a game played out every half inning, even in the ninth, and even if the home team was winning.

That day, the Adriatics came to bat in the bottom of the ninth. They were leading 45-13.

The crowd likely cheered them on for more runs.

Henry Ford, ‘The Vagabonds,’ and the Birthplace of the Charcoal Briquet

By Ken Zurski

In 1919, car-making giant Henry Ford had been eyeing a significant tract of land on the far western portion of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan known as Iron Mountain. Ford’s cousin, Minnie, to whom he was very close, lived there along with her husband E.G. Kingsford. Thanks to his wife’s family connections, Kingsford ran a successful timber business and owned several car dealerships in the area.

Kingsford, of course, is a name synonymous with charcoal briquets, but the backstory has just as much to do with Ford’s keen business sense.

Here’s why:

At the time, Ford had begun wrestling control from his stockholders and purchasing raw materials to be used in making his vehicles. Anything to make his car making process more efficient, he implied. Kingsford had a beat on something Ford desperately sought. So Ford invited Kingsford to go camping with him. To talk business, he explained.

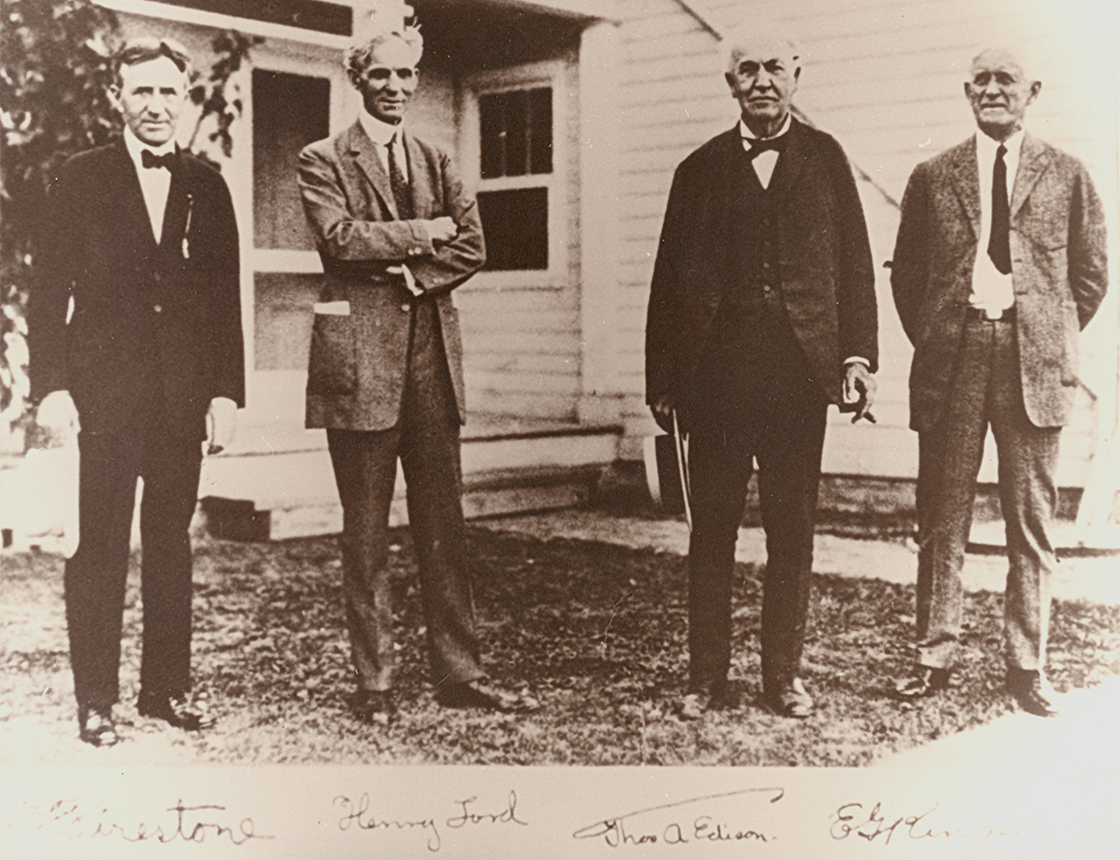

Ford had been making headlines across the country, not just for making cars, but for using one too. Ford went on road trips. The press dubbed it, “auto-camping,” because Ford along with his three close friends, who called themselves “the vagabonds” would travel by automobile during the day then set camps at night. Ford’s camping companions were no slouches. They included Harvey Firestone, the tire company founder; John Burroughs, the conservationist; and inventor Thomas Edison. Their journeys included a jaunt through the Florida Everglades and treks across mountainous regions in West Virginia and New England. Their first trip to the Adirondacks in 1918 was so satisfying they all agreed to make a trip to a new destination every year.

The trips were well-organized, well-stocked and oftentimes well-staffed with cooks and a cleaning crew. Like true campers, though, the formidable men did sleep on folding cots in a ten-by ten canvas tent. Burroughs, in his 80’s and the oldest by age of the four (Ford was in his 50’s), chronicled most of the adventures. He marveled at their resiliency. “Mr Ford seizes an ax and swings it vigorously til there is enough wood for the campfire,” he wrote.

Each year newspapers ran features of “the vagabonds” latest adventure and newsreels of their exploits were shown in movie theaters throughout the country. After all these were prominent American inventors and role models to some like Edison and Ford, who despite their gray hair, and unabashed preference to wear business attire – tight collars, three piece suits and ties – even on the retreats, were “roughing it,” so to speak, in the great outdoors. The papers couldn’t hide the obvious irony of it all. “Millions of Dollars Worth of Brains Off on Vacation,” the headlines blared. Even President Warren G. Harding joined the men briefly for one excursion.

Kingsford must have been pleased and a certainly flattered by Ford’s invitation to join “the vagabonds” in Green Island, New York, a popular fishing spot near Edison’s Machine Works company. Ford had a purpose. He needed land. Specifically, he needed land with timber on it. Nearly one-million board feet a day was used to manufacture the popular Model T’s, whose chassis were made mostly of wood.

Kingsford convinced Ford to buy some flat land near the Menominee River and build a wood distillation plant. Ford heeded his advice and went even further. He would build the plant and an electric dam nearby to power it. Ford hated to waste anything and in the wood distillation process there was always a lot of waste, specifically wood chip ash, or rough charcoal. So Ford had an idea. He mixed the crushed charcoal with a potato starch glue and pressed the blackened goo into a pillow-shaped briquette. When lit, it burned white ash and produced searing heat, but little or no flame.

Ford was not the first person to come up with the idea of charcoal in a briquet. That honor goes to a man named Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer from Philadelphia who patented the idea in 1897. Ford, however, was the first to commercially market it. He advertised the new product as “a fuel of a hundred uses” and perfect for “barbecues, picnics, hotels. restaurants, ships, clubs, homes, railroads, trucks, foundries, tinsmiths, meat smoking, and tobacco curing.” For home use, it was less dangerous than a traditional wood fire, but just as useful. “Briquette fire alone is enough to take the chill off a room,” the instructions informed. “Absence of sparks eliminates this menace to rugs, floors and clothing.”

Ford’s put his signature logo on the charcoal briquettes bags and sold them exclusively at his many car dealerships. When Ford died in 1947, the charcoal business was phased out. Henry Ford II took over and sold the chemical operation to local business men who changed the name to reflect its local heritage: Kingsford Chemical Company. By that time, Kingsford was not just a person, but a city. Thanks to the economical success of Ford’s wood, parts and charcoal plant, the land used to build the original timber business was named in honor of its first industrialist.

His story is rarely told. In short, Kingsford was born in Woodstock, Ontario and moved to Michigan as a young boy. He lived on his parents farm in Fremont before becoming a timber agent and moving to Marquette in the Upper Peninsula. In 1892, Kingsford married Mary Francis “Minnie” Flaherty, Henry Ford’s cousin. Several years later, he signed a contract to become a Ford sales agent in Marquette and eventually moved to Iron Mountain where he bought tracks of land for timber and opened several Ford dealerships. When Ford called to discuss the possibility of using the massive timber resource for his car making, Kingsford answered.

Eventually, the once uncharted land, about five square miles total, was named Kingsford, Michigan.

Despite the distinction, however, Ford, not Kingsford, is prominently associated with the town’s history. Ford was responsible for putting up the large factory, employing hundreds of workers, and building modern houses for the workers and their families to live. Within just one year, in 1920, the population of Kingsford blossomed from a mere 40 residents to nearly 3,000, creating a town out of an enterprise, thanks to Henry Ford.

By the time Ford’s imprint left in 1950, the town of Kingsford was established enough to persevere, although the plant’s closing was a blow economically. After the parts plant it’s doors in the 1960’s, the charcoal business also left; moving operations to Louisville, Kentucky.

Ford’s name is still displayed on several establishments in town: Ford Airport, Ford Hospital and Ford Park are just a few examples. In a a publication honoring the city’s 75th Jubilee, Kingsford is refereed to as “The Town that Ford Built.”

Some might say that’s a slight to Kingsford, the man, who by association convinced Ford to venture out to the remote section of the Upper Peninsula, ultimately invest in some land, and put a city on the map. Today, you have to go to Kingsford, Michigan to get the full story. You’ll see. Ford still gets the credit.

But when it comes to charcoal, we all know whose name is on that big blue and white bag.

Walt Disney, the Early Shorts, and ‘Oswald the Lucky Rabbit’

By Ken Zurski

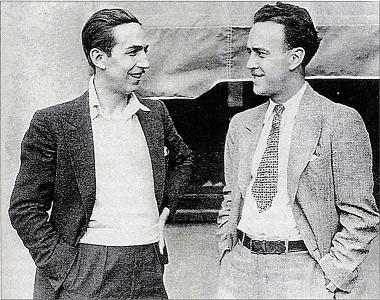

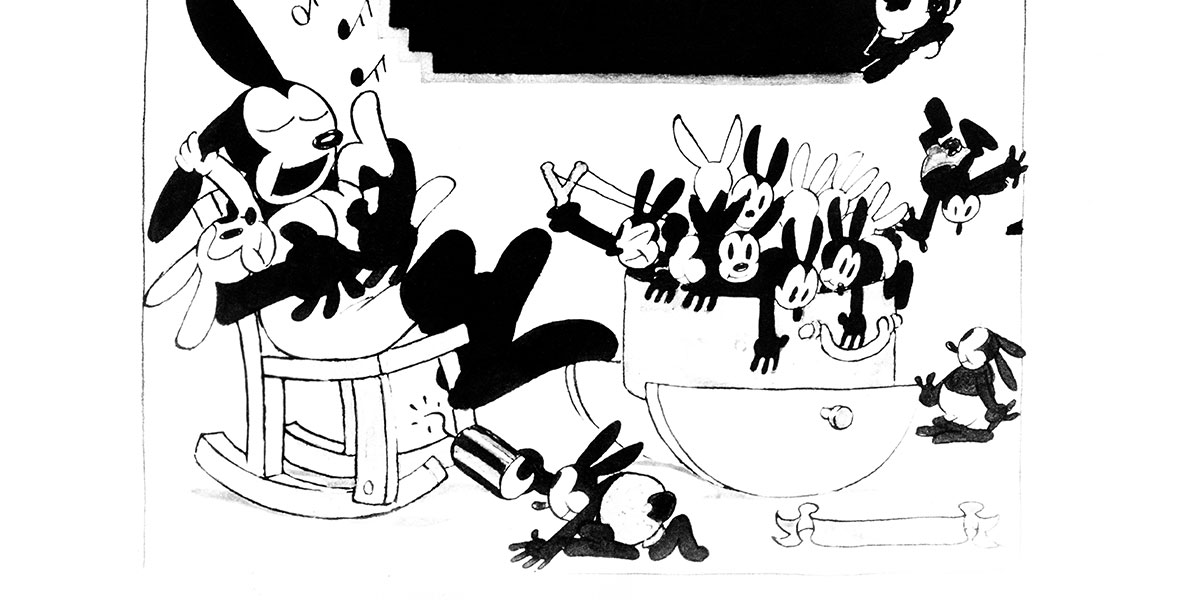

His face was round, his body rubbery. He laughed. He cried. For kicks, he could take off his long supple ears and put them back on again. His name was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and he was the first major animated character created by a man who would later become – and still is – one of the most enduring public figures of our time: Walt Disney.

Walter Elias Disney was just in his twenties when the idea for Oswald came along. A gifted graphic artist from the Midwest, Disney had spent some time overseas during World War I as an ambulance driver and returned to the U.S. to work for a commercial arts company in Kansas City, Missouri. Disney had a knack for business. He partnered with a local artist named Ub Iwerks and together they formed their own company, Iwerks –Disney (switching the name from their first choice of Disney- Iwerks because it sounded too much like a doctor’s office: “eye works”).

They dabbled in animation and soon were making shorts, basically live action films mixed with animated characters. They made a slew of little comedies called Lafflets under the name Laugh-O-Grams. It was a tough sell. Studios backed out of contracts and various offers fell flat.

Disney never gave up and soon they had a series called Alice the Peacemaker based loosely on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Alice was different and seemingly better. They used a new technique of animation, more fluid with fewer cuts and longer stretches of action. Alice, the heroine of the series, was a live person, but the star of the comedies was an animated cat named Julius. The distributor of the Alice shorts, an influential woman named Margret Winkler, had suggested the idea. “Use a cat wherever possible,” she told Disney, “and don’t be afraid to let him do ridiculous things.” Disney and Iwerks let the antics fly, mostly through their feline co-star.

When Alice ran its course and Disney was thinking of another series and character, he wanted it to be an animal. But not a cat, he thought, there were already too many. That’s when a rabbit came to mind. A rabbit he named Oswald.

It was a shaky start. The first Oswald short, Poor Papa, was controversial even by today’s standards. In it, Oswald is overwhelmed by an army – or air force, if you will – of storks each carrying a baby bunny and dropping the poor infants one right after the other upon Oswald’s home. Oswald was after all a rabbit and, well, rabbits have a reputation for being prodigious procreators. But this onslaught of newborns, hundreds it seemed, was just too much for the budding new father. Oswald’s frustration turns to anger and soon he brandishes a shotgun and starts shooting the babies, one by one, out of the sky like an arcade game. The storks in turn fire back using the babies as weapons.

Pretty heady stuff even for the 1920’s, but it wasn’t the subject matter that bothered the head of Winkler productions, a man named Charles Mintz. It was the clunky animation, repetition of action, no storyline, and a lack of character development that drew his ire.

Disney and Iwerks went back to work and undertook changes that made Oswald more likable – and funnier. They made more shorts and audiences began to respond. Oswald the Lucky Rabbit caught on. Soon, Oswald’s likeness was appearing on candy bars and other novelties.

Disney finally had a hit. But the reality of success was met with sudden disappointment. Walt had signed only a one-year contract, now under the Universal banner, and run by Winkler’s former head Mintz. The contract was up and Mintz played hardball. He wanted to change or move animators to Universal and put the artistic side completely in the hands of the studio. Walt was asked to join up, but refused. He still wanted full control. Seeing an inevitable shift, many of Disney’s loyal animators jumped ship, but Walt’s close friend and partner Ub Iwerks stayed on. Oswald was gone, but the prospects of a new company run exclusively by Walt were at hand.

Under Universal’s rule, Oswald’s popularity waned. Mintz eventually gave the series to cartoonist Walter Lantz who later found success in another popular character, a bird, named Woody Woodpecker. Oswald dragged on for years, as cartoons often do, and was eventually dropped.

Disney, meanwhile, needed a new star.

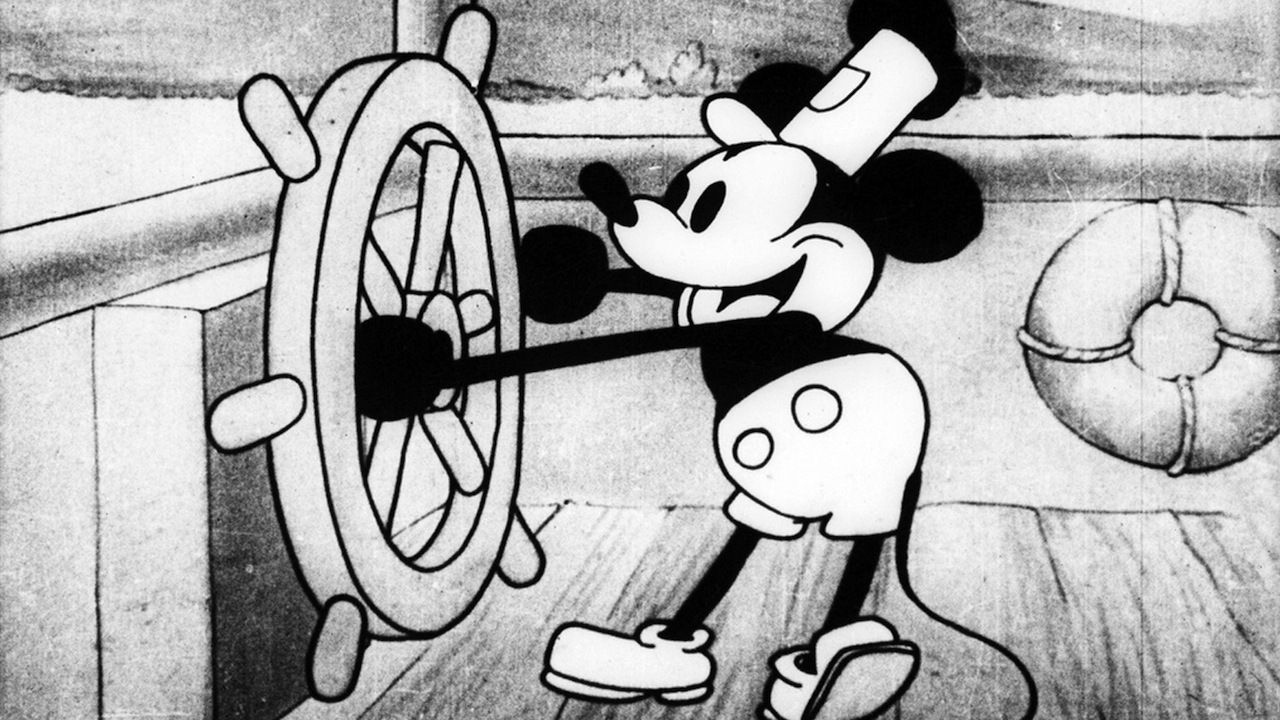

Here’s where it gets better for Walt. In early 1928, Disney was attending meetings in New York when he got word that his contract with Universal would not be renewed. Although he later said it didn’t bother him, a friend described his mood as that of “a raging lion.” Disney soon boarded a train and steamed back west. As the story goes, during the long trip, Disney got out a sketch pad and pencil. He started thinking about a tiny mouse he had once befriended at his old office in Kansas City. He had an idea. He began to draw a character that looked a lot like Oswald only with shorter rounded ears and a long thin tail.

Steamboat Willie starring Mickey Mouse debuted later that year.