History

John L. Young and The Million Dollar Pier

By Ken Zurski

John L. Young was a big deal in the early 20th century. The Atlantic City, New Jersey entrepreneur made lots of money, doled out lots of money, and lived quite comfortably off those who spent their hard earned dollars on his wheeling and dealing. Call it gumption, not greed. Young was a dreamer and had the fortitude to dream big and be rewarded. It also helped build a truly unique american city and in retrospect the beginning of a uniquely American institution, too.

Born in Absecon, New Jersey in 1853, Young came to Atlantic City as a youthful apprentice looking for work. Adept at carpentry, he helped build things at first including the infamous Lucy the Elephant statue that still greets visitors today.

The labor jobs were steady and the money reasonable, but Young was looking for something more challenging – and prosperous. Soon enough, he befriended a retired baker in town who offered Young a chance to make some real dough. The two men pooled their resources and began operating amusements and carnival games along the boardwalk. Eventually they were using profits, not savings, to expand their business.

The Applegate Pier was a good start. They purchased the 600-plus long, two-tiered wooden structure, rehabbed it, and gave it a new name, Ocean Pier, for its proximity to the shoreline. Young built a nine-room Elizabethan- style mansion on the property and fished from the home’s massive open-aired windows. His daily “casts” became a de facto hit on the Pier. Young would wave to the curious in delight as the huge net was pulled from the depths of the Atlantic and tales of “strange sea creatures below” were told. The crowds dutifully lined up every day to see it. They even gave it a name, “Young’s Big New Haul.”

But Young had even bigger aspirations. He promised to build another pier that would cost “a million dollars.” In 1907, the appropriately titled “Million Dollar Pier,” along with a cavernous building, like a large convention hall, opened its opulent doors. It was everything Young had said it would be and more, elegantly designed like a castle and reeking of cash.

Young spared no expense right down to the elaborately designed oriental rugs and velvety ceiling to floor drapery. It was the perfect place to host parties, special events and distinguished guests, including President William Howard Taft who typical of his reputation – and size – spent most of the time in the Million’s extended dining hall. “The pier itself was a glorious profusion of pennants, towers, and elongated galleries, wrote Jim, Waltzer of the Atlantic City Weekly. “It attracted stars, statesmen, and, of course, paying customers.”

Hotel owners along the boardwalk were pleased. Pricey rooms were always filled to capacity and revenues went up each year. Young had built a showcase of a pier and thousands came every summer to enjoy it. But every year near the end of August there was a foreboding sense that old man winter would soon shut down the piers – and profits.

There was nothing business leaders could do about the seasonal weather. In fact, the beginning of fall is typically a lovely time of year on the Jersey Shore. But the start of the school year and Labor Day is traditionally the end of vacation season. In the early 1920’s, by mid-September, the boardwalk and its establishments would become in essence, a ghost town. Something was needed to keep tourists beyond the busy summer season.

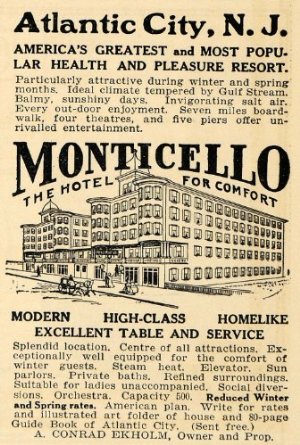

A man named Conrad Eckholm, the owner of the local Monticello Hotel, came up with a plan. He convinced other business owners to invest in a Fall Frolic, a pageant of sorts filled with silly audience participation events like a wheeled wicker chair parade down the street, called the Rolling Chair. It was so popular, someone suggested they go a step further and put a bevy of beautiful young girls in the chairs. Then an even more ingenious proposal came up. Why not make it a beauty or bathing contest?

Immediately the call went out. Girls were wanted, mostly teenagers and unmarried. They were to submit pictures and if chosen receive an all-expense paid trip to Atlantic City for a week of lighthearted comporting. The winner would get a “brand new wardrobe,” among other things. The entries poured in and by September of 1921, the inaugural pageant soon to become known as “Miss America” was set.

Typical of his showmanship and style, John Young offered to host the event at the only place which could do the young ladies justice – The Million Dollar Pier.

In Atlantic City today, the Million Dollar Pier, is even gone by name. A newer half-mile long pier still stands but with a new title, it’s third, The Pier Shops at Caesars Atlantic City, an 80-store shopping mall.

The original Million Dollar Pier was demolished in the 1960’s.

A Telegraph Operator’s Titanic Response

By Ken Zurski

Late in the evening, April 14, 1912, on a passenger liner in the Atlantic Ocean, telegraph operator Harold Cottam was getting ready for bed. Cottam was the only wirelessman on board the RMS Carpathia bound for Gibraltar by way of New York. The day had been busy as usual and Cottam was looking forward to shutting it down for the night.

The radio, however, remained open.

“Why?” he was asked later in an inquiry.

“I was receiving news from Cape Cod.” he replied. “I was looking out for the Parisian, to confirm a previous communication with the Parisian. I had just called the Parisian and was waiting for a reply, if there was one.”

At this point, Cottam might have been asked about allegations, based on the late hour, that he was listening to Cape Race in Newfoundland for English football scores, clearly against regulations. But under oath, he said it was only the Marconi base at Cape Cod he was monitoring. Cottam says he kept the telephone on his head with the hope that before he got into bed, a message would be confirmed.

“So, you were waiting for an acknowledgement [from the Parisian]?”

“Yes, sir,” Cottam conferred

Cottam says he received no word from the Parisian, but did get a late transmission from Cape Cod to relay a message to another ship steaming to New York from England’s Southampton shore. The large ocean liner had been sailing for several days and the messages – mostly personal correspondence for passengers – did not go through. Perhaps Cottam, who was closer, would have better luck. “I was taking the messages down with the hope of re-transmitting them the following morning,” Cottam said. But Cottam didn’t wait until morning. He immediately tried to reach the ship.

“And you did it of your own accord?”

“I did it of my own free will,” he replied

Cottam said he sat down at the telegraph desk and tapped out these words: “From the Carpathia to the Titanic are you aware of a batch of messages for you” The reply came quickly. It wasn’t what Cottam was expecting: CQ followed by D, a general distress call.

“And what did it mean?” he was asked.

“Come at once,” Cottam explained,

“come at once.”

All Hail the Mechanical Pencil and its Lasting Legacy

By Ken Zurski

In 1822 the first patent for a lead pencil that needed no sharpening was granted to two British men, Sampson Mordan and Isaac Hawkins. A silversmith by trade, Mordan eventually bought out his partner and manufactured the new pencils which were made of silver and used a mechanism that continuously propelled the lead forward with each use. When the lead ran out, it was easily replaced.

While Mordan may have marketed and sold the product as his own, the idea for a mechanical pencil was not a new one. In fact, its roots date back to the late 18th century when a refillable-type pencil was used by sailors on the HMS Pandora, a Royal Navy ship that sank on the outer Great Barrier Reef and whose artifacts, including the predated writing utensil, were found in its wreckage.

Mordan’s design notwithstanding, between 1822 and 1874, nearly 160 patents for mechanical pencils were submitted that included the first spring and twist feeds.

Then in 1915, a 21-year old factory worker from Japan named Hayakawa Tokuji designed a more practical housing made of metal and called it the “Ever-Ready Sharp.”

Simultaneously in America, Charles Keeran, an Illinois businessman and inventor, created his own ratcheted-based pencil he similarly called Eversharp.

Keeran claimed individuality and test marketed his product in department stores before submitting a patent. The pencil was so popular that Keeran had trouble keeping up with orders. So to help with production, he partnered with the Wahl Machine company out of Chicago. It was not a good fit. Keeran lost most of his stock holdings in a bad deal and was eventually forced out even though his pencils were making millions annually in sales.

“Built for hard work. Put it on your working force. With no wasteful whittling, no loss of time, it is positive economy,” the ads for the Wahl Eversharp touted. “It’s made with the precision of a wrench.”

Around the same time, in Japan, Tokuji’s factory was leveled by an earthquake.

Tokuji lost nearly everything in the disaster including some members of his family. So to start anew and settle debts he sold the business, began making radios instead, and founded a company that turned into one of the largest manufacturers of electronic equipment in the world.

He named it Sharp after the pencils.

Canned Heat’s Unique Christmas Single with The Chipmunks

By Ken Zurski

In 1968, the LA based boogie/blues band Canned Heat released a Christmas single, The Chipmunk Song, which paired the band with their Liberty Records label mates, the animated – literally – and very fictional group of singing rodents called the Chipmunks.

Canned Heat’s version of “The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late)” wasn’t exactly the same as the Chipmunks’ similarly titled chart-topper in 1958. It was a bluesy number containing humorous dialogue between Canned Heat singer Bob Hite and the voices of the Chipmunks: Simon, Theodore and Alvin, who were all named after record executives at Liberty.

The song was released the year before Canned Heat was asked to appear at a massive music festival in southeastern New York where the band covered Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” and performed their harmonica infused hit “On The Road Again” as an encore.

“On the Road Again” became the unofficial theme of the 1970 documentary movie “Woodstock.”

The Chipmunk Song’s first appearance on a Canned Heat album was in 2005. It was added as a bonus track to the reissue of the band’s second album “Boogie with Canned Heat.” By that time the Chipmunks had received iconic pop culture status and their 1958 version of The Christmas Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late) was already a holiday season staple:

Christmas, Christmas time is near

Time for toys and time for cheer

We’ve been good, but we can’t last

Hurry Christmas, hurry fast

Canned Heat’s version of the song would appear again on the group’s “Christmas Album” released in 2007. The album would feature the Chipmunks cover, along with a few originals and other holiday staples like Jingle Bells and Santa Claus is Coming to Town.

Typical of the boozy, drug-filled lifestyle of the 60’s & 70’s, Canned Heat would go through various lineup changes and tragic circumstances throughout the years. In 1981 after a show at the Palomino Club in Hollywood, lead singer Bob Hite died from an apparent heroin overdose.

In 2000, the band’s producer and drummer Fito de la Parra wrote a revealing tell-all book titled Living the Blues: Canned Heat’s Story of Music, Drugs, Death, Sex and Survival. In it, Parra covers a lot of heavy themes, including the death of Hite, but nothing about the Chipmunks or the song.

However, a biographer on Canned Heat’s official website calls the song an “incongruous move” in the band’s history.

Decide for yourself:

(Source: www.cannedheatmusic.com)

Raymond Weeks, the ‘Father of Veterans Day’

By Ken Zurski

In 1945, after serving in the Navy in World War II, Raymond Weeks returned to his family in Birmingham, Alabama and envisioned a national holiday that would honor war veterans. He picked a day, November 11, a date traditionally designated as Armistice Day marking the end of World War I on the “the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of the year.”

Weeks felt the day should be set aside to honor all veterans of all wars.

So the next year he wrote a letter and personally delivered his petition for a “National Veterans Day 1947” to then Army Chief of Staff, General Dwight Eisenhower.

Because of Weeks’ unrelenting commitment to honor those who bravely served the United States during times of war, the first “Veterans Day” event was held on November 11th 1947 in Birmingham.

In 1954, President Eisenhower officially changed the designation of Armistice Day when he signed a bill which made Veterans Day, November 11th, a federal holiday. The bill was proposed by U.S. Representative Edward Rees of Kansas.

For 38 years after that, Weeks, dubbed the “Father of Veterans Day,” served his hometown of Birmingham as Director of the National Veterans Day Celebration.

Then on November 11, 1982, President Ronald Reagan presented Weeks with the Presidential Citizens Medal.

The President described Weeks as a person who “…devoted his life to serving others, his community, the American veteran, and his nation.”

He added: “So let us go forth from here, having learned the lessons of history, confident in the strength of our system, and anxious to pursue every avenue toward peace. And on this Veterans Day, we will remember and be firm in our commitment to peace, and those who died in defense of our freedom will not have died in vain.”

Weeks died on May 6, 1985 at the age of 76.

(Source: Some text reprinted from Uncompromising Comittment; www.reaganlibrary.archives.gov)

‘Is There a Santa Claus?’: History’s Most Enduring Christmas Related Editorial Was Published in September.

By Ken Zurski

As brothers growing up in Rochester, New York, William and Francis Church were raised in a strict but loving household. Their father, Pharcellus Church, was a newspaper publisher and Baptist minister. He demanded nothing but the best from his boys, who in return, each earned a college degree and joined their father in the newspaper business.

In 1862, however, at the onset of the Civil War, the two brothers followed separate paths. William resigned his post at the New York Times to become a full-time soldier while Francis continued on as a civilian war correspondent.

William earned the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, but left after a year. His superior at the time, General Silas Casey, suggested he start up a newspaper and devote it strictly to the war. William liked the idea so he mustered out and asked his brother to join him. Together they published The Army and Navy Journal and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces, a weekly filled with articles on everyday applications of the war, soldier’s viewpoints, and a critical eye.

“There is not a shadow of a doubt that Fort Sumter lies a heap of ruins,” the first sentence of the first volume read on August 29, 1863.

While the two brothers continued to edit the Journal, and eventually collaborated on a monthly literary magazine, The Galaxy, their legacies are vastly different.

William would go on to become the founder and first president of the National Rifle Association (NRA), while Francis became posthumously known for an editorial he wrote in response to a little girl’s inquisitive letter and inquiry. “I am 8 years old…,” the letter began and ended with an ages old question, “Please tell me the truth. Is there a Santa Claus?”

It was signed: Virginia O’Hanlon 115 W. 95th Street

The editorial appeared without a byline and was buried deep in New York’s The Sun on September 21, 1897.

Only after Francis’ death in 1906 was it revealed that the former war correspondent penned the famous line:

“Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus.”

For Roosevelt’s ‘Rough Riders,’ Nothing Beats a Good Smoke

By Ken Zurski

Colonel Theodore Roosevelt didn’t care much for smoking tobacco which is unusual since almost all the men under his command swore allegiance to it. Pipes, cigars, cigarettes or chewing tobacco, didn’t matter as long as they had it. And if they didn’t have it, well now that was a problem too.

The men in reference here are the “Rough Riders,” and thanks to a new book by American West historian Mark Lee Gardner titled Rough Riders: Teddy Roosevelt , His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill, a broader picture emerges of these men who in the summer of 1898 famously followed their fearless, toothy-grinned, bespectacled leader to Cuba to fight in the Spanish-American War.

One thing that stands out, besides the lack of war experience at first, was their love of a good smoke.

Gardner cites the writings of war correspondent Richard Harding Davis of the New York Herald. Davis had turned down a commissioned offer to serve, a privilege, since Roosevelt’s diverse group included career men, Ivy League graduates, and experienced horse riders, or the so-called “cowboys” from the west. Most men volunteered but it was more like a contest than an enlistment; not everyone who signed up got to go. Davis had the chance to fight, but chose to write about the war instead. This however tormented him so that during the engagements he carried a sidearm “just in case.” And when the situation presented itself, Gardner relates, “[Davis] borrowed a Krag (revolver) and joined in the final charge.”

Davis’ most important job, however, was to tell the story and Roosevelt gave journalists, especially his friends, full access. Later detailing every aspect of battlefield life from a soldier’s perspective, Davis described one thing that seemed to be the biggest morale booster of all: tobacco. “With a pipe the soldier can kill hunger, he can forget that he is wet and exhausted and sick with the heat, he can steady his nerves against the roof of bullets when they pass continually overhead,” Davis wrote.

Gardner points out that there were four agonizing days when no tobacco was in the camp. Likely replacement supplies hadn’t arrived yet from the Cuban port city Siboney where American forces came ashore and supply ships were docked. By this point, the men were hopelessly addicted and each day without tobacco was another day of torture. “They got headaches, became nervous, and couldn’t sleep.” Gardner writes.

Tobacco, however, was not a ration. The men had to pay for the privilege. When a shipment arrived there was “as much excitement in the ranks as when they had charged the San Juan trenches,” Gardner notes. When it seemed like some men would have to do without, one of the Ivy Leaguer’s would step in and offer to pay for the lot, about 85 dollars total, to keep others from suffering.

Smoking helped relieve tension too. When Captain Buckey O’Neill, an experienced frontier lawman from Arizona, noticed some uneasiness in the troops, he calmly walked in front of the crouching men smoking a cigarette. Despite their admiration for such courage, O’Neill, who was hoping to settle the men’s fears by example, was tempting his own fate. “Captain, a bullet is going to hit you” the men shouted from the trenches. O’Neill took a long draw of smoke. “The Spanish bullet isn’t made that will kill me,” he boldly proclaimed. Shortly after, a sharp crack was heard. “Like the snapping of a twig,” Gardner described. It was O’Neill’s teeth breaking. A bullet had entered his mouth and traveled through his head, killing him instantly.

“He never even moaned,” a trooper noted.

Most soldiers though had the good sense to wait until the battle was over before lighting up. It was during this downtime – the time in between the bloody skirmishes – that the cravings hit the hardest.

Even Davis in a letter to his father admitted that smoking was an important diversion and one he personally endorsed. “I have to confess that I never knew how well off I was until I got to smoking Durham tobacco,” he wrote.“And I’ve only got a half bag left.”

Some soldiers were so desperate, Davis noted, that they made their own tobacco out of “grass, roots, tea and dried horse droppings.”

Davis graciously doesn’t expound on how that might have tasted.

Elbridge Gerry, the Blue Bottle Fly, and the Shaping of the Constitution

By Ken Zurski

Massachusetts statesman Elbridge Gerry was of the cantankerous and crafty sort. He typically came late to engagements and was usually the first to tell the host that he had finally arrived. This is the mark he made on the Constitutional Convention in May of 1787 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia during the drafting of the nation’s first constitution.

Actually he made no physical mark on the Constitution, refusing to sign the document and disagreeing with most of the other 40-plus delegates on how much power to give the government in relation to its people. Gerry had signed the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation, but the Constitution was different. There were too many variables and not enough unity, he argued. “If we do not come to some agreement among ourselves. “Gerry maintained, “some foreign sword will probably do it for us.”

In September, after the final draft of the Constitution was reached, Gerry along with two others, Edmund Randolph and George Mason, all agreed the document needed to protect the rights of people of whom whose basic freedoms should be added. Freedoms similar to the one Mason, the governor of Virginia, had drafted in his home state.

Therefore, they argued, it was incomplete.

Mason urged the framers, now drafters, to stay on as long as needed to finish the task. Gerry seconded the motion. The answer from all the other delegates, however, was a resounding, “No.”

Whether or not any of the other participants agreed such rights were necessary wasn’t the point. Most had been away from their wives and families for months and were ready to leave. In addition, they were weakened by the heat and humidity and disgusted by the cramped sleeping quarters of two to four men per room which during a severe infestation of the blue bottle fly kept the windows shut and the smells in.

Frankly, they were just plain sick of fly’s, the heat, and each other.

Many nearly walked out a month before in August, but trudged on to complete the task. But staying longer? That was not an option for those who actually signed the document. They went home.

Several years later, James Madison’s proposal of twelve amendments was approved by Congress.

It was appropriately titled the Bill of Rights.

Mark Twain, Nikola Tesla and the “Irregular” Solution

By Ken Zurski

Around the same time Nikola Tesla was making waves in America for inventing an alternating current (AC) electrical power source and engaging in a “War of Currents” with his former employer and now adversary Thomas Edison, one of the Serbian-born scientist and engineer’s lesser known laboratory experiments took an unexpected and unusual turn.

It was in the 1890’s and Tesla had perfected what he called the Oscillator, or an AC generator that introduced a reciprocating piston rather than the standard rotating coils to generate power. Tesla used steam to drive the piston back and forth and a shaft connected to the piston moved the coils through the magnetic field. The result was higher frequencies and more current than conventional generators.

He patented this machine and unveiled it to great curiosity at the Chicago World’s Fair. “Mr. Tesla has taken what may be called the core of a steam engine and the core of an electrical dynamo, given them a harmonious mechanical adjustment, and has produced a machine which has in it the potentiality of reducing to the rank of old metal half the machinery at present moving on the face of the globe,” the New York Times raved.

Proving the “mad scientist” was never satisfied with his own work and always tried to improve what he had already achieved, when Tesla returned to his New York lab he attempted to use compressed air instead of steam. He built this on a platform that vibrated at a high rate, driving the piston when the column of air was compressed and then released. Even though it didn’t generate enough electricity to power a lighting system, Telsa was amused nonetheless, especially when he stood on the platform. “The sensation experienced was as strange as agreeable,” he wrote, “and I asked my assistants to try. They did so and were mystified and pleased like myself.”

Only one problem. Each time Tesla or one of his assistants stepped off the platform, they had to run to the toilet room. The reason was obvious, especially to Tesla. “A stupendous truth dawned upon me. Some of us, who had stayed longer on the platform, felt an unspeakable and pressing becessity which had promptly been satisfied.”

Basically, they had a sudden urge to empty their bowels.

Intrigued, Tesla kept experimenting and ordering his assistants to “eat meals quickly” and “rush back to the lab.” Tesla may have failed in an attempt to upgrade his own machine, he thought, but succeeded in the prospect at least of using electricity to cure a number of digestive issues.

But to be sure, he unsuspectingly enlisted the help of a friend.

Mark Twain and Tesla were seemingly unlikely acquaintances. In addition to his writing, Twain was a failed inventor, or at least a failed backer of inventions, like the automatic typesetting machine which he poured thousands of dollars into and even more into finding a workable electric motor to power it. Unsuccessful, Twain read about Tesla’s AC steam-powered motor generator and gushed at its simplicity and ingenuity. “It is the most valuable patent since the telephone,” Twain wrote without a hint of his usual sarcasm.

Tesla had sold his invention to lamp maker George Westinghouse’s company which also impressed Twain who lost a sizable portion of his own fortune on the typesetter machine. So at some point the two men met and Twain visited Tesla’s lab. The result is a famous photograph of Twain in the foreground acting as a human conductor of electricity as Tesla or an assistant looms mysteriously in the background. But Tesla fondly remembers helping his friend too. “[Twain] came to the lab in the worst shape,” Tesla recalls, “suffering from a variety of depressing and dangerous elements.”

As the story goes, Twain stepped on the vibrating platform as Tesla had suggested. After a few minutes, Tesla begged him to come down. “Not by a jugfull,” insisted Twain, apparently enjoying himself. When Tesla finally turned the machine off, Twain lurched forward looked at Tesla and pleadingly yelled: “Where is it?”

He was, of course, asking for direction to the toilet room. “Right over there,” Tesla responded chuckling. But Tesla knew he had done Twain a favor. “In less than two months, he regained his old vigor and ability of enjoying life to the fullest extent.”

Of course, Tesla never did patent or market a machine for such a specific purpose and Twain didn’t talk about it, so it’s mostly lost to time, unlike the photograph. Both men now have an important place in history and numerous books are written about them. Twain’s recollections are mostly in his own hand. But the story of Twain’s visit to Tesla’s lab and Twain’s resulting step on the oscillating platform is found in Tesla’s versions, not Twain’s.

Perhaps, as one Tesla biographer suggests, it was all a big practical joke, which certainly – and quite remarkably – turns the tables on both men’s reputations considering Twain was the humorist and Tesla the brain.

Despite this, and knowing the outcome, even if it was only intended for a laugh, both men were likely pleased with the results.

But for completely different reasons.

How An Insane Asylum May Have Inspired the Iconic Twin Spires of Churchill Downs

By Ken Zurski

In 1794 a man named Isaac Hite, a Virginia Militia Officer, came to the Kentucky frontier with other surveyors to stake claim on scenic tracts of land given to them for fighting in the French and Indian War. They founded the properties as promised, but also encountered more Indians. And so in his newly adopted home now known as Anchorage, just outside of Louisville, Hite was killed by the hostile natives.

Or was he?

The introduction of a book containing Hite’s personal journal disputes claims he was struck down, but rather died from “natural causes,” at the age of 41. His companions, the book asserts, “had died years before, and violently, while taking Kentucky and holding it against the Indians.” One theory is that Hite was injured by Indians and later died from his wounds. But how he died isn’t as important as what he left behind. A parcel of land where he settled, started a family, and ran a mill and tannery.

Through the years, and for many generations, Hite’s descendants tended the land known as Fountain Bleu and an estate they dubbed Cave Springs Plantation. Then in 1869, the family sold the parcel to the State of Kentucky. The reason the state wanted it was explicit: open a new government institution for troubled youths near its largest city.

The rural, secluded site of Hite’s Cave Springs was the perfect setting for such a facility. Originally known as the “Home for Delinquents at Lakeland,” it was named after the path that led to it’s front gate, Lakeland Drive. It was converted – or just transformed – into a mental hospital in 1900 and renamed to reflect the often misunderstood and misdiagnosed residents who inhabited its 192 beds. “The Central Kentucky Lunatic Asylum,” as it was now called, became the state’s fourth facility for such a purpose.

As with any institution for the mentally challenged, in the early 20th century, the day-to-day operations were marred by allegations of abuse, malfeasance and deaths. Massive overcrowding was reported in the mid 1900’s and in 1943 the state grand jury found the asylum was committing people that were neither insane nor psychotic. One man was reportedly admitted for simply spitting in a courtroom. While the scientific merits of electric shock therapy and lobotomies were morally judged, the reports of fires, murders, and multiple escapes at the facility consistently filled the newspapers. It was a horror show.

Since many died on the grounds, many were buried there too. So stories of ghosts and haunted spirits are attributed to the site. “Have the mournful souls that died at Central State remained at the only home most of them ever knew?” a local ghost hunter asked.

The grounds, however, are also tied to the storied history of the Louisville underground. Literally, a series of caves and tunnels used before prohibition to move shipments – perhaps contraband during the Civil War – from the river docks to downtown buildings. Since a small cave existed before a tunnel was added, Hite was probably the first to discover the hole through the rock on his newly claimed property. Later after the state took over, the cave was reinforced with brick walls and pillars and used as cold storage mostly for perishable items like large cans of sauerkraut. The inside was reportedly lined with so many sauerkraut cans it was given a name by the locals: Sauerkraut Cave.

In the back of the cave a tunnel was built which has its own back door, so there was a natural entryway and a man made exit. Many morose stories about the lunatic asylum involve Sauerkraut Cave, including tales of residents who may have used it as an escape route or more graphic reports of pregnant patients who went there to give birth and abandon their babies. Those who visit the site today say without lights the cave would have been too dark and too flooded to navigate. Still, desperate patients may have drowned or froze to death trying.

Regardless of how many people perished on site or off, the general scientific worth of the experiments, and the ghastly stories that followed, the building itself was considered a architectural wonder at the time it was built.

Looking like a medieval castle in the front, the three story structure with wing additions on each side was made of solid red brick with stone trim. The small pane windows in the main building had segmental arches with brick molding and the facade was highlighted by a columned porch and railing. On the side of the main building is two identical towers, shooting high into the air and inspired by the Tudor revival style used in its original design. It quickly became one of the Louisville area’s most distinctive and important buildings when it opened its doors in 1869. By the time it came down, in the late 20th century, it had represented something else entirely.

But it’s legacy may be more lasting than you think.

Enter Joseph Dominic Baldez.

Baldez wasn’t even born yet when the asylum building was built, but eventually worked for the firm that created it. D.X Murphy & Bros was an offshoot of another firm established by Harry Whitestone. In the 1850’s. Whitestone, an Irish immigrant, designed some of the city’s elaborate homes, hotels and hospitals, including the Home for Delinquents on Lakeland Drive. When Whitestone retired in 1881, his top assistant Dennis Xavier (D.X.) Murphy took over the business. Baldez began working for Murphy at the age 20.

In 1894, Baldez, a native of Louisville and a a self-effacing, self-taught draftsman, started work on a project at the area’s racetrack known as Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby, the prestigious race for three-year-old thoroughbreds held every year at the beginning of May.

For 20 years since the track was built, the seating had been on the backstretch, facing west, a mistake, since the late afternoon sun would be directly in spectators eyes. So a new larger structure was planned on the other side, facing east, or directly near the one-eighth pole on the stretch. The D.X. Murphy firm was hired and the young Baldez, at 24, was commissioned to design the new stands. He went to work constructing a 250-foot long slanted seating area of vitrified brick, steel and stone with a back entrance wall lobby which on its own was not only fancy and stylish, but efficient too. It was graciously received: “The new grandstand is simply a thing of beauty,” raved the Louisville Commercial. The new grandstand included a “separate ladies section” and “toilet rooms,” the paper noted.

The Courier-Journal also chimed in: “With its monogram, keystone and other ornate architecture, it will compare favorably with any of the most pretentious office buildings or business structures on the prominent thoroughfares.”

Then there are the candles on the birthday cake, so to speak.

The Twin Spires.

Whether Baldez was asked to include it, or came up with the idea on his own is unclear. His diagrams clearly show what he intended to do: put one large spire on either side of the grandstand for ornamental decoration. Each spire would be 12 feet wide, 55 feet tall, and sit 134 feet apart from center to center. The base shape was octagonal for strength and surrounded by eight rounded windows which were designed to stay open (although later were glassed over to keep birds out). Above the windows was a decorative Feur-de-lis, or a “flower lily” shape, flanked by two roses which were decorative rather than symbolic since the race didn’t become the “Run for the Roses” until the late 20th Century.

Although others, like the track president at the time Col. Matt J. Winn, greatly admired the spires, Baldez was indifferent about his work. “They aren’t any architectural triumph,” he argued. “But are nicely proportioned.”

Although no one can be absolutely certain, and little about Baldez is known other than his designs, the building which housed the mental patients on Lakeland Drive on the former property of one of its first residents may have sparked the idea for the Twin Spires at Churchill Downs. The comparisons are justifiable. Both have large steeples, two in fact, and the tops of each are similar in design. Plus, Baldez knew the asylum building well by working at the firm that built it.

Perhaps as some suggest, the name Churchill Downs was also an inspiration for Baldez’s “steeples.” Churchill, however, was not a religious connotation, but the surname of the original owners John and Henry Churchill who leased the land to their cousin Colonel Meriwether Lewis Clark who subsequently built the track on the property.

Unfortunately, only pictures can tell the story now. The original asylum building was torn down in 1996 to make way for expansion. The Sauerkraut Cave is still there , but only as a curiosity. It’s entrance is marred by graffiti and only the brave – or crazy – dare enter it today. Other than the cemetery, the cave is the last vestige of the old grounds.

Baldez never told anyone what drew his interest in adding the adornment to the roof of Churchill Downs, but he gets credit for a lasting legacy, not only to horseracing, but to American culture in general.

Col. Winn knew it. “Joe, when you die, there’s one monument that will never be taken down,” he reportedly told Baldez.

He was talking about those famous Twin Spires.