Unrememebered History

Walt Disney, the Early Shorts, and ‘Oswald the Lucky Rabbit’

By Ken Zurski

His face was round, his body rubbery. He laughed. He cried. For kicks, he could take off his long supple ears and put them back on again. His name was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and he was the first major animated character created by a man who would later become – and still is – one of the most enduring public figures of our time: Walt Disney.

Walter Elias Disney was just in his twenties when the idea for Oswald came along. A gifted graphic artist from the Midwest, Disney had spent some time overseas during World War I as an ambulance driver and returned to the U.S. to work for a commercial arts company in Kansas City, Missouri. Disney had a knack for business. He partnered with a local artist named Ub Iwerks and together they formed their own company, Iwerks –Disney (switching the name from their first choice of Disney- Iwerks because it sounded too much like a doctor’s office: “eye works”).

They dabbled in animation and soon were making shorts, basically live action films mixed with animated characters. They made a slew of little comedies called Lafflets under the name Laugh-O-Grams. It was a tough sell. Studios backed out of contracts and various offers fell flat.

Disney never gave up and soon they had a series called Alice the Peacemaker based loosely on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Alice was different and seemingly better. They used a new technique of animation, more fluid with fewer cuts and longer stretches of action. Alice, the heroine of the series, was a live person, but the star of the comedies was an animated cat named Julius. The distributor of the Alice shorts, an influential woman named Margret Winkler, had suggested the idea. “Use a cat wherever possible,” she told Disney, “and don’t be afraid to let him do ridiculous things.” Disney and Iwerks let the antics fly, mostly through their feline co-star.

When Alice ran its course and Disney was thinking of another series and character, he wanted it to be an animal. But not a cat, he thought, there were already too many. That’s when a rabbit came to mind. A rabbit he named Oswald.

It was a shaky start. The first Oswald short, Poor Papa, was controversial even by today’s standards. In it, Oswald is overwhelmed by an army – or air force, if you will – of storks each carrying a baby bunny and dropping the poor infants one right after the other upon Oswald’s home. Oswald was after all a rabbit and, well, rabbits have a reputation for being prodigious procreators. But this onslaught of newborns, hundreds it seemed, was just too much for the budding new father. Oswald’s frustration turns to anger and soon he brandishes a shotgun and starts shooting the babies, one by one, out of the sky like an arcade game. The storks in turn fire back using the babies as weapons.

Pretty heady stuff even for the 1920’s, but it wasn’t the subject matter that bothered the head of Winkler productions, a man named Charles Mintz. It was the clunky animation, repetition of action, no storyline, and a lack of character development that drew his ire.

Disney and Iwerks went back to work and undertook changes that made Oswald more likable – and funnier. They made more shorts and audiences began to respond. Oswald the Lucky Rabbit caught on. Soon, Oswald’s likeness was appearing on candy bars and other novelties.

Disney finally had a hit. But the reality of success was met with sudden disappointment. Walt had signed only a one-year contract, now under the Universal banner, and run by Winkler’s former head Mintz. The contract was up and Mintz played hardball. He wanted to change or move animators to Universal and put the artistic side completely in the hands of the studio. Walt was asked to join up, but refused. He still wanted full control. Seeing an inevitable shift, many of Disney’s loyal animators jumped ship, but Walt’s close friend and partner Ub Iwerks stayed on. Oswald was gone, but the prospects of a new company run exclusively by Walt were at hand.

Under Universal’s rule, Oswald’s popularity waned. Mintz eventually gave the series to cartoonist Walter Lantz who later found success in another popular character, a bird, named Woody Woodpecker. Oswald dragged on for years, as cartoons often do, and was eventually dropped.

Disney, meanwhile, needed a new star.

Here’s where it gets better for Walt. In early 1928, Disney was attending meetings in New York when he got word that his contract with Universal would not be renewed. Although he later said it didn’t bother him, a friend described his mood as that of “a raging lion.” Disney soon boarded a train and steamed back west. As the story goes, during the long trip, Disney got out a sketch pad and pencil. He started thinking about a tiny mouse he had once befriended at his old office in Kansas City. He had an idea. He began to draw a character that looked a lot like Oswald only with shorter rounded ears and a long thin tail.

Steamboat Willie starring Mickey Mouse debuted later that year.

John L. Young and The Million Dollar Pier

By Ken Zurski

John L. Young was a big deal in the early 20th century. The Atlantic City, New Jersey entrepreneur made lots of money, doled out lots of money, and lived quite comfortably off those who spent their hard earned dollars on his wheeling and dealing. Call it gumption, not greed. Young was a dreamer and had the fortitude to dream big and be rewarded. It also helped build a truly unique american city and in retrospect the beginning of a uniquely American institution, too.

Born in Absecon, New Jersey in 1853, Young came to Atlantic City as a youthful apprentice looking for work. Adept at carpentry, he helped build things at first including the infamous Lucy the Elephant statue that still greets visitors today.

The labor jobs were steady and the money reasonable, but Young was looking for something more challenging – and prosperous. Soon enough, he befriended a retired baker in town who offered Young a chance to make some real dough. The two men pooled their resources and began operating amusements and carnival games along the boardwalk. Eventually they were using profits, not savings, to expand their business.

The Applegate Pier was a good start. They purchased the 600-plus long, two-tiered wooden structure, rehabbed it, and gave it a new name, Ocean Pier, for its proximity to the shoreline. Young built a nine-room Elizabethan- style mansion on the property and fished from the home’s massive open-aired windows. His daily “casts” became a de facto hit on the Pier. Young would wave to the curious in delight as the huge net was pulled from the depths of the Atlantic and tales of “strange sea creatures below” were told. The crowds dutifully lined up every day to see it. They even gave it a name, “Young’s Big New Haul.”

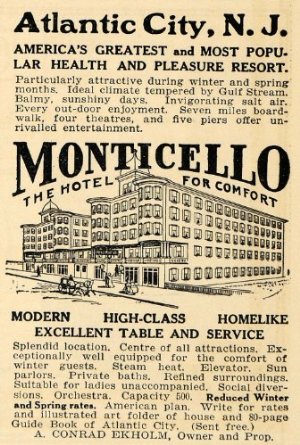

But Young had even bigger aspirations. He promised to build another pier that would cost “a million dollars.” In 1907, the appropriately titled “Million Dollar Pier,” along with a cavernous building, like a large convention hall, opened its opulent doors. It was everything Young had said it would be and more, elegantly designed like a castle and reeking of cash.

Young spared no expense right down to the elaborately designed oriental rugs and velvety ceiling to floor drapery. It was the perfect place to host parties, special events and distinguished guests, including President William Howard Taft who typical of his reputation – and size – spent most of the time in the Million’s extended dining hall. “The pier itself was a glorious profusion of pennants, towers, and elongated galleries, wrote Jim, Waltzer of the Atlantic City Weekly. “It attracted stars, statesmen, and, of course, paying customers.”

Hotel owners along the boardwalk were pleased. Pricey rooms were always filled to capacity and revenues went up each year. Young had built a showcase of a pier and thousands came every summer to enjoy it. But every year near the end of August there was a foreboding sense that old man winter would soon shut down the piers – and profits.

There was nothing business leaders could do about the seasonal weather. In fact, the beginning of fall is typically a lovely time of year on the Jersey Shore. But the start of the school year and Labor Day is traditionally the end of vacation season. In the early 1920’s, by mid-September, the boardwalk and its establishments would become in essence, a ghost town. Something was needed to keep tourists beyond the busy summer season.

A man named Conrad Eckholm, the owner of the local Monticello Hotel, came up with a plan. He convinced other business owners to invest in a Fall Frolic, a pageant of sorts filled with silly audience participation events like a wheeled wicker chair parade down the street, called the Rolling Chair. It was so popular, someone suggested they go a step further and put a bevy of beautiful young girls in the chairs. Then an even more ingenious proposal came up. Why not make it a beauty or bathing contest?

Immediately the call went out. Girls were wanted, mostly teenagers and unmarried. They were to submit pictures and if chosen receive an all-expense paid trip to Atlantic City for a week of lighthearted comporting. The winner would get a “brand new wardrobe,” among other things. The entries poured in and by September of 1921, the inaugural pageant soon to become known as “Miss America” was set.

Typical of his showmanship and style, John Young offered to host the event at the only place which could do the young ladies justice – The Million Dollar Pier.

In Atlantic City today, the Million Dollar Pier, is even gone by name. A newer half-mile long pier still stands but with a new title, it’s third, The Pier Shops at Caesars Atlantic City, an 80-store shopping mall.

The original Million Dollar Pier was demolished in the 1960’s.

A Telegraph Operator’s Titanic Response

By Ken Zurski

Late in the evening, April 14, 1912, on a passenger liner in the Atlantic Ocean, telegraph operator Harold Cottam was getting ready for bed. Cottam was the only wirelessman on board the RMS Carpathia bound for Gibraltar by way of New York. The day had been busy as usual and Cottam was looking forward to shutting it down for the night.

The radio, however, remained open.

“Why?” he was asked later in an inquiry.

“I was receiving news from Cape Cod.” he replied. “I was looking out for the Parisian, to confirm a previous communication with the Parisian. I had just called the Parisian and was waiting for a reply, if there was one.”

At this point, Cottam might have been asked about allegations, based on the late hour, that he was listening to Cape Race in Newfoundland for English football scores, clearly against regulations. But under oath, he said it was only the Marconi base at Cape Cod he was monitoring. Cottam says he kept the telephone on his head with the hope that before he got into bed, a message would be confirmed.

“So, you were waiting for an acknowledgement [from the Parisian]?”

“Yes, sir,” Cottam conferred

Cottam says he received no word from the Parisian, but did get a late transmission from Cape Cod to relay a message to another ship steaming to New York from England’s Southampton shore. The large ocean liner had been sailing for several days and the messages – mostly personal correspondence for passengers – did not go through. Perhaps Cottam, who was closer, would have better luck. “I was taking the messages down with the hope of re-transmitting them the following morning,” Cottam said. But Cottam didn’t wait until morning. He immediately tried to reach the ship.

“And you did it of your own accord?”

“I did it of my own free will,” he replied

Cottam said he sat down at the telegraph desk and tapped out these words: “From the Carpathia to the Titanic are you aware of a batch of messages for you” The reply came quickly. It wasn’t what Cottam was expecting: CQ followed by D, a general distress call.

“And what did it mean?” he was asked.

“Come at once,” Cottam explained,

“come at once.”

All Hail the Mechanical Pencil and its Lasting Legacy

By Ken Zurski

In 1822 the first patent for a lead pencil that needed no sharpening was granted to two British men, Sampson Mordan and Isaac Hawkins. A silversmith by trade, Mordan eventually bought out his partner and manufactured the new pencils which were made of silver and used a mechanism that continuously propelled the lead forward with each use. When the lead ran out, it was easily replaced.

While Mordan may have marketed and sold the product as his own, the idea for a mechanical pencil was not a new one. In fact, its roots date back to the late 18th century when a refillable-type pencil was used by sailors on the HMS Pandora, a Royal Navy ship that sank on the outer Great Barrier Reef and whose artifacts, including the predated writing utensil, were found in its wreckage.

Mordan’s design notwithstanding, between 1822 and 1874, nearly 160 patents for mechanical pencils were submitted that included the first spring and twist feeds.

Then in 1915, a 21-year old factory worker from Japan named Hayakawa Tokuji designed a more practical housing made of metal and called it the “Ever-Ready Sharp.”

Simultaneously in America, Charles Keeran, an Illinois businessman and inventor, created his own ratcheted-based pencil he similarly called Eversharp.

Keeran claimed individuality and test marketed his product in department stores before submitting a patent. The pencil was so popular that Keeran had trouble keeping up with orders. So to help with production, he partnered with the Wahl Machine company out of Chicago. It was not a good fit. Keeran lost most of his stock holdings in a bad deal and was eventually forced out even though his pencils were making millions annually in sales.

“Built for hard work. Put it on your working force. With no wasteful whittling, no loss of time, it is positive economy,” the ads for the Wahl Eversharp touted. “It’s made with the precision of a wrench.”

Around the same time, in Japan, Tokuji’s factory was leveled by an earthquake.

Tokuji lost nearly everything in the disaster including some members of his family. So to start anew and settle debts he sold the business, began making radios instead, and founded a company that turned into one of the largest manufacturers of electronic equipment in the world.

He named it Sharp after the pencils.

The Men Behind the Central American Fruit War and the Birth of the ‘Banana Republic’

By Ken Zurski

In Douglas Preston’s book The Lost City of the Monkey God, the true tale of a modern day exploration to find an ancient city deep in the Honduran rainforest, the author presents a compelling history of the troubled Central American republic right down to its most exotic, and at one time, most corrupt export.

In Douglas Preston’s book The Lost City of the Monkey God, the true tale of a modern day exploration to find an ancient city deep in the Honduran rainforest, the author presents a compelling history of the troubled Central American republic right down to its most exotic, and at one time, most corrupt export.

Bananas.

Of course, narcotics and drug smuggling would soon take over as Honduras’ most nefarious trade and it’s why today many foreigners are warned not to travel there. Preston and his team took the risk anyway. There was a mysterious and lost city to find and poisonous snakes, diseased mosquitoes and dangerous drug cartels were all part of the adventure.

Preston’s fast paced and informative book is the reward. It’s a fun read. But as the author points out, there was a precursor to the problems in Honduras which began in the late 19th century and was just as heated, and in retrospect, just as cutthroat as the drug trade today.

And it starts with two American fruit sellers.

In 1885, a man named Andrew Preston (a distant cousin of the author), was a Boston entrepreneur who co-founded the Boston Fruit Company. His plan was simple: revolutionize the banana market by using fast steamships to move the perishable fruit quickly back to the U.S. before they spoiled. Until then bananas were rarely transported to the Eastern seaboard because sailing ships could not move them fast enough. Preston’s speedy steamers did the trick. Bananas soon became one of the most popular delicacies in America.

Preston bought 40 acres of plantation land in Honduras, and the Boston Fruit company became the larger United Fruit Company. “United Fruit and the other fruit companies that soon followed became infamous for their political and tax machinations, engineered crops, bribery and exploitation of workers,” the author Preston writes in his book.

But that’s not all. Another American named Samuel Zemurray would enter the fray. Zemurray was a Russian immigrant who worked as pushcart peddler in Alabama. As a teenager, Zemurray traveled to Boston and watched as Preston’s banana ships arrived. He noticed crews throwing out large batches of bananas that were beginning to ripen. So Zemurray gathered them up at no cost of his own, threw them on a railroad car, and announced to grocers along the line that he had bananas to sell far less than the shipper’s price. He quickly bankrolled over 100,000 dollars, bought five thousand acres of banana groves in Honduras and opened up his own fruit shipping business named the Cuyamel Fruit Company. For a time, everything was going swimmingly for Zemurray in Honduras. Then politics got in the way.

Honduras and its people were struggling economically and the government sought financial help. The British banks loaned the republic millions of dollars that they soon found out could not be paid back. The Brits threatened military action to collect it, but the President of the Untied States at the time, William Howard Taft, would hear none of it. He ordered his Secretary of State, Philander Knox, to recruit financier J.P Morgan and buy up the loan at fifteen cents on the dollar. Morgan struck a deal with the Honduran government to occupy its customs offices and collect all the tax receipts to pay off the debt.

Zemurray was hit hard. The crafty exporter known to locals as “Sam the Banana Man” had worked out a favorable tax-free deal with Honduran officials and Morgan’s “penny a pound” tax would surely put him out of business. But Zemurray would not go without a fight. He went directly to D.C. and straight to Knox’s office to protest. Knox nearly kicked him out the door. Pay up and do what’s right for your country, Knox implied. When an angry Zemurray left, Knox put a secret security tail on him just in case he tried to do something foolish.

Zemurray was done dealing with his own government. Instead, he went to the deposed former president of Honduras, Manuel Bonilla, who was flat broke and living in New Orleans. Apparently dodging Knox’s security detail, Zemauury met Bonilla and convinced him to lead a path back to power, led by support from Hondurans who thought Morgan’s tax plan would threaten their sovereignty. It worked. Under pressure from the Honduran people, the current president resigned and Bonilla was reelected president. He immediately awarded Zemurray with a plum 25-year tax free concession, a $500,000 loan and nearly 25,000 prime acres of coastline land. The American got his tax break back and all the credit for the coup. As Preston writes: ” He had outmaneuvered Knox, successfully defied the US government, poked J.P Morgan in the eye, and ended up a much wealthier man.”

According to Preston, this would be that start of a long and contentious relationship involving banana companies in America and the government of Honduras. Soon the country would earn the nickname “Banana Republic, a term first introduced by writer, O’ Henry in 1904, in his fictional novel Cabbages and Kings, describing an imaginary country, Anchuria, as a “small, maritime banana republic,” meaning a country reliant on one crop, usually in a dominate or corrupt way. Today, the term is cavalierly used and represents countries with more politically shrewd intentions than just selling fruit, but the point is made.

In the book, before author Preston and his team sets out to find the “Lost City of the Monkey God,” (hence the title), he wraps up Andrew Preston and Samuel Zemurray’s story.

Faced with a price war on bananas, Andrew Preston’s United Fruit, eventually bought out Zemurray’s Cuyamel Fruit Company paying him $31 million in U.S. dollars. Trouble followed. Preston died in 1924 and the Great Depression hit. The stock declined and the company went into disarray. Zemuarry saw a chance to get back in. He convinced enough United shareholders to vote by proxy and put him in charge. He fired all of Preston’s board members, gained control of the struggling company and brought it back to respectability. Later, he gave up the business, and using his own fortune funded numerous humanitarian causes in Honduras – all for the better.

But as Preston points out, as colorful as the history of Zemurray and others in this saga was, and long before the drug runners came nearly century later, “the fruit companies left a dark colonist legacy that has hung like a miasma over Honduras ever since.”

And its due in part to America’s insatiable appetite for bananas and the men who sold them.

Before Judy sang ‘Over the Rainbow,’ the Silent Movie Version of ‘The Wizard of Oz’ Was Oddly Different

By Ken Zurski

In 1925, when Judy Garland was only three years old, a movie version of “The Wizard of Oz” was released that was loosely based on a stage play of the same name which in itself was loosely based on L. Frank Baum’s famous book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

There was no singing of “Somewhere over the Rainbow” in this version. In fact, there was no singing at all. “Talkies” as they were known in the movie business, hadn’t been perfected yet. This was a silent movie and compared to the musical film that was released fifteen years later in 1939, this version, as were other early adaptations of Baum’s book, remains somewhat of an enigma.

Here’s why.

When Baum’s book came out in 1900 it became an instant best seller. Two years later, under Baum’s direction a play based on the book was set to music and opened in Chicago. The title was shortened and the story was altered slightly. The main difference between the book and the stage adaptation, however, was an obvious one. Baum wrote the book specifically for children, while the play was geared for adults.

Due to the popularity of the stage version, a 13-minute live action short was released that mostly confused viewers familiar with the book. The first full-length movie version then in 1925 was also based on the play and differed quite a bit from Baum’s original story

In the film, Dorothy and three farmhands arrive in Oz after a tornado sweeps them away. The Wizard proclaims Dorothy is the long lost Princess of Oz, but the Prime Minister, named Kruel, wants nothing to do with her. The prince, however, named Kynd, welcomes the princess’s return and accuses the farmhands of kidnapping her.

To thwart the Prince’s soldiers, the farmhands, who are madly in love with Dorothy, dress up in disguise: one as a scarecrow and one in sheets of tin. The two men are eventually caught but the third farmhand dons a lion’s costume, scares the guards, and helps the others escape. The Tin Man eventually sides with Kruel and the whole tangled affair leads to a showdown in a tower between the Scarecrow and the Tin Man, both of whom lose Dorothy’s affections to the handsome prince.

The movie ends as the 1939 version does, when Dorothy wakes up from a dream.

“‘The Wizard of Oz’ goes way beyond even our wildest expectations,” proclaimed I.E. Chadwick, president of Chadwick pictures, upon its release. “A thing of great beauty and fantasy. Marvelously entertaining. A knockout!”

The movie was one of a series of films that Chadwick’s studio produced. “Each production an achievement,” Chadwick proudly announced.

The movie’s top billing went to a popular comedian named Larry Semon, who played the scarecrow and directed the film. His real life wife, Dorothy Dwan, played Dorothy. The movie was advertised as a comedy and it did well at first. ‘It’s a Whiz!” was one excited description. But it didn’t last. By the time the Garland version appeared, the silent film had long since been forgotten.

Yet, the movie may best be remembered for the introduction of the larger-than-life figure who played The Tin Man. “Large” in this instance, referring to his outwardly size. The relative newcomer’s portliness would eventually become his trademark, but for this role, it was more a liability. Even a fellow actor questioned why a man of his girth would – or even could – wear a suit made of tin. “What are you going to do about the costume?” he asked.

Oliver Hardy as it turned out would go on to have greater success as the bigger half, literally, of the comedic duo, Laurel and Hardy.

But the most glaring mistake of the early film may be the absence of many of Baum’s most enduring characters, including two that featured prominently in Garland’s version: the Wicked Witch and Dorothy’s little dog, Toto.

In fact, in the stage version, Toto was replaced by a cow named Imogene.

When Soap Was Taxed, Bathing Was Optional, and Dying Was Too Expensive

By Ken Zurski

Beginning in 1712 and continuing for nearly 150 years, the British monarchy used soap to raise revenue, specifically by taxing the luxury item. See, at the time, using soap to clean up was considered a vain gesture and available only to the very wealthy. The tax, of course, was on the production of soap and not the participation. But because of the high levy’s imposed, most of the soap makers left the country hoping to find more acceptance and less taxes in the new American colonies.

Cleanliness was not the issue, although it never really was. Soap itself had been around for ages and used for a variety of reasons not necessarily associated with good hygiene. The Gauls, for example, dating back to the 5th Century B.C., made a variation of soap from goat’s tallow and beech ashes. They used it to shiny up their hair, like a pomade.

Even before soap was introduced, rather ingenious ways of cleaning oneself emerged. The Hittites in the 16th century washed their hands with plant ashes dissolved in water. And the Greeks and Romans, who never used soap, would soak in hot baths then beat their bodies with twigs or use an instrument called a strigil, basically a scrapper with a blade, that would scrape away sweat and dirt of the body, similar to what a razor does with hair stubble.

So when actual soap was introduced in the late Middle Ages it had always been considered exclusively for the privileged. Therefore, later when it was mass produced, the British imposed hefty taxes on it as did many other luxury items, like wallpaper, windows and playing cards.

Thank goodness in centuries to follow some common sense emerged.

Or did it.

In 1902, psychologist and chemist, William Thomas Sedgwick released a book titled Principles of Sanitary Science and Public Heath which was a compilation of lectures he gave as a professor of biological sciences at MIT.

In it, Sedgwick extolled the virtues of good personal hygiene to keep infectious diseases away. “The absence of dirt,” he urged with conviction, “is not merely an aesthetic adornment.”

Basically, he was telling everyone to take a bath.

It wasn’t that most people didn’t understand the merits of taking a bath, but it was a chore. Water had to be warmed and transported and would chill quickly. Oftentimes families would use the same water in a pecking order that surely forced the last in line to take a much quicker one than the first. When the baths were over the water had to be lugged outside and dumped.

In the later half of the 19th century, as running water became more widespread, bathtubs became less mobile. Most were still bulky, steel cased and rimmed in cherry or oak. Fancy bronzed iron legs held the tub above the floor.

Ads from the time encouraged consumers to think of the tub as something other than just a cleaning vessel. “Why shouldn’t the bathtub be part of the architecture of the house?” the ads asked. After all, if there is going to be such a large object in the home, it might as well be aesthetically pleasing.

Getting people to actually use it, however, that was another matter.

Sedgwick had medical reasons to back up his claims. As an epidemiologist, he studied diseases caused by poor drinking water and inferior sanitation practices. Good scientific research, he implied, should be all the proof needed. But attitudes and decades old habits needed to be amended too. “It follows as a matter of principle,” Sedgwick wrote, “that personal cleanliness is more important than public cleanliness.” He had a point. Largely populated cities were dirty messes, full of billowing black smoke from factories, coal dust, and discarded garbage and waste. Affixing blame for such conditions was more popular than actually doing something about it. Sedgwick focused on self-awareness to make his point. “A clean body is more important than a clean street,” he stressed.”Sanitation alone cannot hope to effect these changes. They must come from scientific hygiene carefully applied throughout long generations.”

People, it seemed, had to literally be frightened into washing up.

Something Sedgwick understood, but fought to change.

“Cleanness,” he wrote in his book, ”was an acquired taste.”

By this time, soap was being widely used, relatively inexpensive, and no longer taxed in Great Britain. William Ewart Gladstone, the Prime Minister at the time, finally put an end to the soap tax in 1853, nearly a century and a half after it was imposed. In doing so, however, he faced a substantial revenue loss. So to make up for this financial scourge he introduced death duties, basically a tax on the widow of a dead spouse. “This woman by the death of her husband became absolutely penniless,” announced the Common Cause, citing a recurring example.

With that, Gladstone might have argued that using soap might actually help your cause.

(Sources: How Did It Begin? The Origins of Our Curious Customs and Superstitions by Dr. R. & L. Brasch; various internet sites)

Abraham Lincoln’s Eldest Son Has a Sea Named After Him

By Ken Zurski

Robert Todd Lincoln, President Abraham Lincoln’s first son, outlived his father by 26 years. He also lived 19 years more than his mother, who died at the age of 63. As for his three younger brothers, tragically, they all died young, including the Lincoln’s third son, Willie, who succumbed to illness in the White House at the age of 11. Robert was a teenager at the time of Willie’s death. And yet, despite being the only Lincoln child to live to an old age, Robert’s adult life is understandably overshadowed by the legacy of his father.

But Robert Todd Lincoln lived a fascinating life of nearly 83 years. A life filled with military service, politics, great wealth and something he and not his famous father can claim: a sea named after him.

The 25-thousand square miles of the the Lincoln Sea encompasses a location between the Arctic Ocean and the channel of the Nares Strait between the northernmost Qikiqtaaluk region of Canada and Greenland. Scientists today will point out its geographical and oceanic importance, like most seas, but not much more.

It’s desolate, extreme, and doesn’t bear resemblance to a conventional sea at all. It’s almost completely covered with ice. Due to its year-round ice cover, not many have seen the Lincoln Sea up close, or make a point to visit. The nearest town in Nunavut Canada is so remote it is almost always uninhabited and appropriately named Alert, just in case someone may stumble upon it.

When most people find out there is a sea named Lincoln their immediate instinct is to conclude that it is in honor of the 16th president.

But it’s not.

Here’s why.

In 1881, Robert Todd Lincoln was President James Garfield’s Secretary of War when explorer and fellow soldier Lieutenant Adolphus Greely took a polar expedition financed by the government to collect astronomical and meteorological data in the high Canadian Arctic. A noted astronomer named Edward Israel was part of Greely’s crew. Secretary Lincoln reluctantly approved the risky venture.

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, as it was called, was mostly smooth sailing at first followed by a harrowing and deadly outcome. After discovering many uncharted miles along the northwest coast of Greenland including a new mountain range they named Conger Range, Lt. Greely and the crew of the Proteus were forced to abandon several relief sites due to lack of supplies. They retreated to Cape Sabine where they hunkered down for the winter with limited food rations.

Months later, in July of 1884, nearly three years after the expedition began, a rescue ship Bear finally reached the encamped crew. It was a sobering sight. In all, 19 of the 25-man crew, including Israel had perished in the harsh conditions.

Greely survived.

Even within his own department, Lincoln was criticized for not dispatching a second relief ship (the first one failed to make it through the ice). He rebuked the claims and defended his own actions by basing the decision on information provided to him by others. “Hazarding more lives,” as he put it, was not an option. Greely also blamed Secretary Lincoln for his crew’s fate.

But that was all. Most people understood how dangerous the mission was and Lincoln outlasted the backlash. He issued a court-martial for an outspoken War Department official named William Hazen, and gave Greely a pass, although the Lieutenant’s comments irritated him.

The naming of the Lincoln Sea was a bonus for the Secretary, of course. Although it’s easy to understand why Greely – if in fact he personally named the sea after his military boss – was motivated to do so, especially as the expedition was going well, his actions after the disastrous mission would suggest otherwise. No record exists as to whether Lincoln was flattered by the attribution.

The naming itself is odd. Since President Abraham Lincoln had hundreds of cities, institutions and streets named after him, including the town of Lincoln in Illinois, which was named for Lincoln, the lawyer, before he even became president, you would think the sea distinction would be more identifiable. Perhaps the Robert T. Lincoln Sea would have been more appropriate. But that’s not the case. It’s the Lincoln Sea, plain and simple, on maps and atlases and in literature. So the confusion with the President is understandable.

Robert Todd Lincoln continued to serve as Secretary of War after Garfield’s assassination and through successor Chester Arthur’s presidential term. Under Benjamin Harrison, he served a short stint as U.S minster to the United Kingdom and eventually left public service. In 1893, Lincoln invested in the popular Pullman rail cars, made a fortune, and lived comfortably for the remaining years of his life. He died on July 26, 1926, just six days shy of his 83rd birthday.

And whether he liked it or not, the ice-covered and relatively unknown Lincoln Sea, is a part of Robert Todd Lincoln’s legacy.

Not his father’s.

Canned Heat’s Unique Christmas Single with The Chipmunks

By Ken Zurski

In 1968, the LA based boogie/blues band Canned Heat released a Christmas single, The Chipmunk Song, which paired the band with their Liberty Records label mates, the animated – literally – and very fictional group of singing rodents called the Chipmunks.

Canned Heat’s version of “The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late)” wasn’t exactly the same as the Chipmunks’ similarly titled chart-topper in 1958. It was a bluesy number containing humorous dialogue between Canned Heat singer Bob Hite and the voices of the Chipmunks: Simon, Theodore and Alvin, who were all named after record executives at Liberty.

The song was released the year before Canned Heat was asked to appear at a massive music festival in southeastern New York where the band covered Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” and performed their harmonica infused hit “On The Road Again” as an encore.

“On the Road Again” became the unofficial theme of the 1970 documentary movie “Woodstock.”

The Chipmunk Song’s first appearance on a Canned Heat album was in 2005. It was added as a bonus track to the reissue of the band’s second album “Boogie with Canned Heat.” By that time the Chipmunks had received iconic pop culture status and their 1958 version of The Christmas Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late) was already a holiday season staple:

Christmas, Christmas time is near

Time for toys and time for cheer

We’ve been good, but we can’t last

Hurry Christmas, hurry fast

Canned Heat’s version of the song would appear again on the group’s “Christmas Album” released in 2007. The album would feature the Chipmunks cover, along with a few originals and other holiday staples like Jingle Bells and Santa Claus is Coming to Town.

Typical of the boozy, drug-filled lifestyle of the 60’s & 70’s, Canned Heat would go through various lineup changes and tragic circumstances throughout the years. In 1981 after a show at the Palomino Club in Hollywood, lead singer Bob Hite died from an apparent heroin overdose.

In 2000, the band’s producer and drummer Fito de la Parra wrote a revealing tell-all book titled Living the Blues: Canned Heat’s Story of Music, Drugs, Death, Sex and Survival. In it, Parra covers a lot of heavy themes, including the death of Hite, but nothing about the Chipmunks or the song.

However, a biographer on Canned Heat’s official website calls the song an “incongruous move” in the band’s history.

Decide for yourself:

(Source: www.cannedheatmusic.com)

‘Is There a Santa Claus?’: History’s Most Enduring Christmas Related Editorial Was Published in September.

By Ken Zurski

As brothers growing up in Rochester, New York, William and Francis Church were raised in a strict but loving household. Their father, Pharcellus Church, was a newspaper publisher and Baptist minister. He demanded nothing but the best from his boys, who in return, each earned a college degree and joined their father in the newspaper business.

In 1862, however, at the onset of the Civil War, the two brothers followed separate paths. William resigned his post at the New York Times to become a full-time soldier while Francis continued on as a civilian war correspondent.

William earned the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, but left after a year. His superior at the time, General Silas Casey, suggested he start up a newspaper and devote it strictly to the war. William liked the idea so he mustered out and asked his brother to join him. Together they published The Army and Navy Journal and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces, a weekly filled with articles on everyday applications of the war, soldier’s viewpoints, and a critical eye.

“There is not a shadow of a doubt that Fort Sumter lies a heap of ruins,” the first sentence of the first volume read on August 29, 1863.

While the two brothers continued to edit the Journal, and eventually collaborated on a monthly literary magazine, The Galaxy, their legacies are vastly different.

William would go on to become the founder and first president of the National Rifle Association (NRA), while Francis became posthumously known for an editorial he wrote in response to a little girl’s inquisitive letter and inquiry. “I am 8 years old…,” the letter began and ended with an ages old question, “Please tell me the truth. Is there a Santa Claus?”

It was signed: Virginia O’Hanlon 115 W. 95th Street

The editorial appeared without a byline and was buried deep in New York’s The Sun on September 21, 1897.

Only after Francis’ death in 1906 was it revealed that the former war correspondent penned the famous line:

“Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus.”