History

The Once Mysterious and Often Misrepresented Origins of ‘Taps’

By Ken Zurski

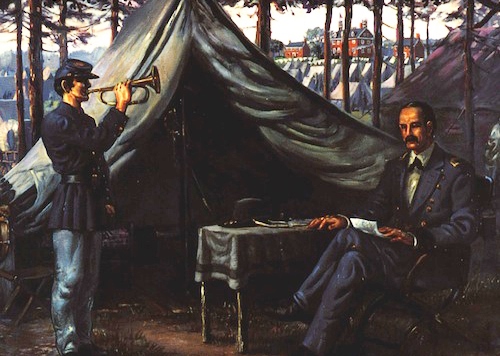

In July of 1862, while a bedraggled group of Union soldiers rested in camp after an bloody and costly week of fighting near Richmond, Virginia known as the Seven Days Battle, Brigadier General Daniel Butterfield decided to make some changes to the military protocol commonly referred to as the bugler’s evening roll call.

Butterfield sent word to his company’s bugler, a man named Oliver Wilcox Norton, to meet him directly at the officer’s tent. According to Norton, Butterfield showed him some notes he had scribbled in pencil on the back of an envelope and asked him to sound it off on his bugle. “I did this several times,” Norton later described, “playing the music as written.” Butterfield adjusted it by ear and Norton played it for him again. “After getting it to his satisfaction he directed me to sound that call thereafter in place of the regulation call.”

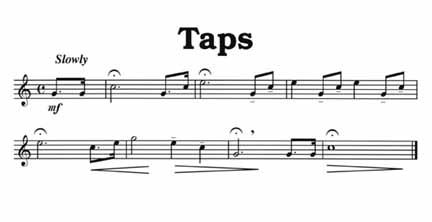

Butterfield had modified the regulation call known as “Tattoo,” or at least the last 5 bars of it, into a 24-note call that was in the general’s own words, “smoother, more melodious and musical.”

“Tattoo,” later changed to “Scott’s Tattoo” for better distinction, refers to the former War of 1812 general Winfield Scott, who supposedly wrote the tune, although he likely only copied a centuries old medley.

Butterfield who was injured and recovering from battle sought to change it – or at least alter it slightly. For some reason, Butterfield thought Scott’s version was too formal sounding. So he came up with another shorter version that’s now more widely known as “Taps,” referring to a drum beat that often followed the call.

“I think no general order was issued from Army headquarters authorizing the substitution of this for the regulation call,” Norton asserts, “but as each brigade commander exercised his own discretion in such minor matters, the call was gradually taken up through the Army of the Potomac.”

Norton gives Butterfield credit for composing “Taps,” but the general himself accepted no such distinction. He chose others to thank for helping him, specifically his wife who wrote down the notes while Butterfield whistled it to her. Being a commander in the Union Army meant that Butterfield knew how to play the bugle as a way of signaling his troops. But as Butterfield admits, he could not read or write music. “I practiced a change in the call until I had it suit my ear,” he claims.

Butterfield, a native New Yorker, rose quickly through the military ranks as colonel of the 12th Regiment of the New York State Militia to commander of the 3rd brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, and eventually Major General after the Peninsular Campaign which included the Seven Days Battle, a crucial turning point for the South. Later Butterfield would serve as a chief of staff for “Fighting Joe Hooker,” the commander of the Army of the Potomac, who fought incessantly with other Union generals and drank like a fish.

Butterfield and Hooker generally liked each other, which caused others to dislike Butterfield simply by association.

Butterfield however had his own flaws. He was snappish, hot-tempered and pushy. In the spring of 1863 , General Hooker suffered a crushing and embarrassing defeat to Lee’s army at Chancellorsville and was reprimanded and reassigned. (Butterfield would eventually fight in Gettysburg, be awarded the Medal of Honor for his role in the Battle of Gaines Mill, and serve on President Grant’s staff. But all that would come later).

In 1862, after a fierce and arduous week-long campaign, Butterfield and his division were recouping by the James River at Harrison’s Landing counting losses and awaiting word from another general, George B. McClellan, who was said to be retreating back to their position after his supply line was cut. That’s when Butterfield decided to give the standard “lights out” call a tuneful change.

Butterfield claims he had used the variation of the “Tattoo” notes before he presented them to Norton. While his troops were marching, he blew the call as an order to halt or lie down. “The men rather liked their call and would sing my name to it,” Butterfield humorously recounted. “’Dan, Dan, Dan Butterfield,’ [they sang] to the notes when the call came.” In times of trying circumstances, he added, they sometimes sang “Damn, Damn, Damn, Butterfield” instead.

Butterfield did not remember his bugler by name, but does not dispute that it was likely Norton to whom he showed the notes.

Of course the general’s recollections, as is Norton’s, comes in 1898, some 35 years after the fact, so memories of that day may be somewhat distorted. Butterfield was 67 at the time he finally revealed his side of the story.

Amazingly, both men’s responses came only after and an article appeared in Century magazine which basically posed this unanswered question: Where did Taps come from?

Had Norton not written a letter to the editor in response to the magazine article and the editor had not contacted Butterfield directly for his thoughts, the true history of “Taps” might still be unknown. Butterfield died in 1901, only two years after the article was written.

Until then, he took no credit or told anyone his connection to the song.

But the origin of “Taps” as a ceremonial song has even deeper and more romanticized roots. The earliest reference to its official use during a funeral comes up during the Peninsular Campaign. A soldier in Captain John Tidball’s Battery A, 2nd artillery was buried on the field while the battery was hiding in the woods. Tidball felt the customary firing of the three musket volley salute might alarm both sides into a resumption in fighting. So he had the bugler play “Taps,” or some variation of it, instead.

In another account, which began to circulate in the mid-20th century, a Union captain named Robert Ellicombe was with his men in a battle at Harrison’s Landing in Virginia when he heard the moans of a dying soldier nearby. Ellicombe bravely risked his own life to retrieve the soldier who was lying in a grassy area that separated the two sides. With musket balls whizzing over his head, Ellicombe crawled on his stomach and pulled the boy’s body out of danger. Sadly, though, by the time they reached safety, the soldier was dead. That’s when Ellicombe realized the boy was wearing a confederate uniform. When he looked closer he discovered something even more startling. The soldier was his own son.

In another account, which began to circulate in the mid-20th century, a Union captain named Robert Ellicombe was with his men in a battle at Harrison’s Landing in Virginia when he heard the moans of a dying soldier nearby. Ellicombe bravely risked his own life to retrieve the soldier who was lying in a grassy area that separated the two sides. With musket balls whizzing over his head, Ellicombe crawled on his stomach and pulled the boy’s body out of danger. Sadly, though, by the time they reached safety, the soldier was dead. That’s when Ellicombe realized the boy was wearing a confederate uniform. When he looked closer he discovered something even more startling. The soldier was his own son.

As the story goes, Ellicombe’s son was studying music in the south and joined the confederate army without telling his father. When Ellicombe checked the s boy’s pocket he found a piece of paper with musical notes written on it. He asked the commanding officer if he could have a military band play the notes at his son’s funeral. His request was denied because the boy was a confederate. But as a concession, they told him, he could have one musician play the notes on one instrument. Ellicombe picked the bugle. The song, as you may have already guessed, was “Taps.”

The story of Ellicombe and his son, however, is not true. Historians have disputed it as simply a tall tale, a good yarn to tell around the campfire. In fact, Captain Ellicombe may not even exist. One good researcher traced the story back to Robert Ripley of “Ripley’s Believe or Not” who used the father and son version of “Taps” to great dramatic effect on his TV show in the late 1940’s. Whether Ripley knew it was pure fiction, didn’t matter. Most of Ripley’s features were subject to scrutiny anyway. But even the Ellicombe story prompted a biographer of Ripley’s to remark: “The denouement of this is a coincidence incredible even by Rip’s standards.”

Ripley apparently tried to pass the story off as the origination of “Taps,” rather than its funeral connotation, which might make more sense.

Either way, it’s fake.

Believe this, however. Norton and Butterfield were real; and together they solved the mystery of “Taps” origins over a century ago.

“Taps” is now the military’s most recognizable and mournful song. It is played to symbolize honor and respect during military funerals, wreath laying ceremonies, flag raisings and other memorial services. It’s often accompanied by a traditional gunfire salute. Butterfield had no idea at the time he made the adjustment to “Scott’s Tattoo ” that it would eventually be used for such a meaningful and solemn purpose.

After all, Scott’s version of “Tattoo,” wherever it came from, was a bit of a devilish thing.

“Tattoo”was also called “Tap-Toe” and derived from a Dutch term doe dan tap toe, or “to turn off the taps.” The song was a signal for men to put out all fires and all lights at night and most importantly stop drinking, hence the “tap” reference. In Scott’s earliest incarnation it was called many things like “Lights Out.” or “Extinguish The Lights.” Later the modified or softer version would be referred to as “Butterfield’s Lullaby.” After lyrics were added (but seldom used), it was often referred to as “Day is Done,” the first line.

Day is done, gone the sun,

From the lake, from the hills, from the sky;

All is well, safely rest, God is nigh.

Fading light, dims the sight,

And a star gems the sky, gleaming bright.

From afar, drawing nigh, falls the night.

Thanks and praise, for our days,

‘Neath the sun, ‘neath the stars, neath the sky;

As we go, this we know, God is nigh.

Sun has set, shadows come,

Time has fled, Scouts must go to their beds

Always true to the promise that they made.

While the light fades from sight,

And the stars gleaming rays softly send,

To thy hands we our souls, Lord, commend.

During the Civil War, the men knew “Taps” as signal of order and didn’t mince words or actions when it sounded in camp.

They knew what to do, even if they didn’t much care for it.

So they appropriately called it, “Go to Sleep.”

Johnny Aitken, the Brick Test, and the First Indy 500

By Ken Zurski

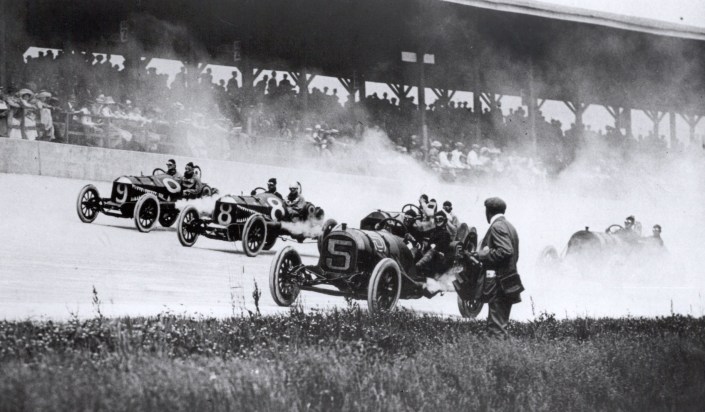

On September 11 1909, at the Speedway in Indianapolis, race car driver Johnny Aitken hopped into his six-cylinder National motor vehicle, the same one he used to break speed and distance records, and gave the engine a go. Like a shot, he drove over several hundred yards of newly laid bricks.

Track officials on hand kept a close eye on the ground, specifically the bricks, which were being considered as a possible replacement for the original “crushed stone” surface. Ever since the track opened earlier that year, the stones, gravel really, was proving to be costly – not only in maintenance, but in lives too.

Just a month before on Aug 9, the first long distance car race took place over the oval track. It was a disaster. A driver’s mechanic who rode shotgun during the race was killed along with two spectators. The race was scheduled for 300 miles, but was mercifully stopped at 235 miles. The drivers and their machines were not the issue. The problem was the track. The stones were too rough and loose. The frequent tire blow outs and debris thrown in driver’s faces led to dangerous and deadly results. The unfortunate victims that day may have been the latest, but certainly not the first, fatalities at the track. Something needed to change.

But what would work?

The National Paving Brick Manufactures Association chimed in. They pitched their product as sturdy and reliable even under racing conditions. But their persuasive bias alone wasn’t enough. It was a costly venture, so track officials needed to see it for themselves. They had crews set down a few hundred yards of bricks and they asked one of the local drivers to help. Run over it, they instructed. Johnny Aitken happily obliged.

Aitken, nicknamed “Happy,” was an Indianapolis native who began testing cars at the National Motor Vehicle Company before racing them full-time with all the derring-do he could muster. Aitken was pretty darn good at driving. He won a few sanctioned races, set speed records for distance and supported another Indiana man, a bicyclist turned car aficionado named Carl Fisher, who used profits from a compressed gas headlight he invented to help finance, along with a few other money men, a showcase track built over farmland in Aitken’s hometown. He called it the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

- Carl Fisher

Fisher, now track president, was not in attendance when Aitken tested the new bricks, but was eagerly awaiting word. Although resistant at first, since attendance numbers went up after races where someone was killed, Fisher knew that the new sport needed its “heroes” alive, not dead. The newspaper’s reporting, however, was typically less sympathetic and more flippant. “The [killings] only served to increase the excitement,” the Indianapolis News enthused after a driver and his mechanic where thrown from their vehicle to their deaths. The next racing day, the News observed: “There were more women in the crowd…and they appeared to be the most interested spectators.”

Fisher read the papers, heard the outcries from critics, and could no longer ignore the truth. The track was unsafe. He considered changing to a concrete surface at first, before deciding on bricks. However, they would have to be subject to vigorous scrutiny, he insisted, before opening his pocketbook.

After the initial run over the brick surface, Aitken turned his vehicle around and did the same thing again. About a dozen or so track employees waved off the dust and smoke and immediately inspected the bricks for damage. There was none. The next test, however, would be even more revealing.

This time Aitken positioned his vehicle directly on the bricks. Two heavy duty ropes were tied to the front of each tire and secured to a couple posts held firmly by a concrete base. Aitken got the signal and gunned the engine. The tires spun wildly in place creating a massive smoke cloud, but little else. When it was over, not one brick was missing; not a chip out of place. That sealed it. The project was given the go ahead. The bricks would cover the full two-and a half mile track.

- Laying the bricks

Fisher promised the bricks would be installed in two weeks, a gross miscalculation. He even scheduled an air and dirigible show on the grounds just to keep interest up, but when work on the track and new grandstands took longer than anticipated, he was forced to cancel the event. The overall cost of the brick installation ballooned to $700,000 nearly triple the amount Fisher originally budgeted.

On May 30, 1911, a Tuesday, driver Ray Harroun in a Marmon Wasp won the inaugural Indianapolis 500 with an average speed of just over 74 mph. Or did he? Historians still debate who actually finished the six-hour race first. Another driver Ralph Mulford claimed he was ahead of Harroun at the end, but lost count and went an extra “insurance” lap just to be sure. By the time he crossed the finish line for the second time, Harroun was already celebrating.

Regardless of who actually won the race, nearly 80-thousand enthusiastic fans cheered the drivers on to the very end. “They had seen their hands weaken on the steering wheel,” the Indianapolis Star reported. “They had seen their drawn faces filled with anguish of intense hardship, and time after time they had seen them risk their lives in the speed arena” As for Harroun’s apparent victory: “There were but four tire changes,” the winning vehicle’s manufacturer boasted the next day. The bricks, they subtlety implied, made the difference. “Three of the original ‘Firestone’ tires finished the race.” The track later picked up the moniker, “Brickyard.”

But there was a tragedy. Sam Dickson, a mechanic for the car driven by Arthur Greiner, never made it home. When Greiner’s car lost a tire and ran off the course it looked like it might somersault through the infield’s tall meadow grass. Instead it came to a sudden and horrifying halt. “Rather than keep going,” wrote author Charles Leerhsen, “the car stopped in mid-maneuver, so that it stood straight up, balancing for a moment on its steaming grille.” Then it slowly flopped forward. Greiner was lucky, he was chucked from the cockpit and survived, but Dickson never left his seat and was crushed under the vehicle’s weight. The race was never stopped.

Johnny Aiken also participated in the first Indy 500. He completed 125 laps before a broken connecting rod ended his day.

He did, however, lead the first lap.

Aitken left auto racing in 1917. He worked to promote Peugeot vehicles and even traveled to France during the war to tour their large car making factory. Returning home, he developed “the cough.” The Spanish Flu epidemic had been spreading quickly overseas. The former race car driver recovered from his initial bout of influenza, but only briefly. Soon enough bronchial pneumonia set in. Aitken died on October 15, 1918.

He was 33.

(Sources: Blood and Smoke: A True Tale of Mystery, Mayhem and the Birth of the Indy 500, Charles Leerhsen; Indianapolis Star May 31, 1911; various internet sites)

Mark Twain, Nikola Tesla and the “Irregular” Solution

By Ken Zurski

Around the same time Nikola Tesla was making waves in America for inventing an alternating current (AC) electrical power source and engaging in a “War of Currents” with his former employer and now adversary Thomas Edison, one of the Serbian-born scientist and engineer’s lesser known laboratory experiments took an unexpected and unusual turn.

It was in the 1890’s and Tesla had perfected what he called the Oscillator, or an AC generator that introduced a reciprocating piston rather than the standard rotating coils to generate power. Tesla used steam to drive the piston back and forth and a shaft connected to the piston moved the coils through the magnetic field. The result was higher frequencies and more current than conventional generators.

He patented this machine and unveiled it to great curiosity at the Chicago World’s Fair. “Mr. Tesla has taken what may be called the core of a steam engine and the core of an electrical dynamo, given them a harmonious mechanical adjustment, and has produced a machine which has in it the potentiality of reducing to the rank of old metal half the machinery at present moving on the face of the globe,” the New York Times raved.

Proving the “mad scientist” was never satisfied with his own work and always tried to improve what he had already achieved, when Tesla returned to his New York lab he attempted to use compressed air instead of steam. He built this on a platform that vibrated at a high rate, driving the piston when the column of air was compressed and then released. Even though it didn’t generate enough electricity to power a lighting system, Telsa was amused nonetheless, especially when he stood on the platform. “The sensation experienced was as strange as agreeable,” he wrote, “and I asked my assistants to try. They did so and were mystified and pleased like myself.”

Only one problem. Each time Tesla or one of his assistants stepped off the platform, they had to run to the toilet room. The reason was obvious, especially to Tesla. “A stupendous truth dawned upon me. Some of us, who had stayed longer on the platform, felt an unspeakable and pressing becessity which had promptly been satisfied.”

Basically, they had a sudden urge to empty their bowels.

Intrigued, Tesla kept experimenting and ordering his assistants to “eat meals quickly” and “rush back to the lab.” Tesla may have failed in an attempt to upgrade his own machine, he thought, but succeeded in the prospect at least of using electricity to cure a number of digestive issues.

But to be sure, he unsuspectingly enlisted the help of a friend.

Mark Twain and Tesla were seemingly unlikely acquaintances. In addition to his writing, Twain was a failed inventor, or at least a failed backer of inventions, like the automatic typesetting machine which he poured thousands of dollars into and even more into finding a workable electric motor to power it. Unsuccessful, Twain read about Tesla’s AC steam-powered motor generator and gushed at its simplicity and ingenuity. “It is the most valuable patent since the telephone,” Twain wrote without a hint of his usual sarcasm.

Tesla had sold his invention to lamp maker George Westinghouse’s company which also impressed Twain who lost a sizable portion of his own fortune on the typesetter machine. So at some point the two men met and Twain visited Tesla’s lab. The result is a famous photograph of Twain in the foreground acting as a human conductor of electricity as Tesla or an assistant looms mysteriously in the background. But Tesla fondly remembers helping his friend too. “[Twain] came to the lab in the worst shape,” Tesla recalls, “suffering from a variety of depressing and dangerous elements.”

As the story goes, Twain stepped on the vibrating platform as Tesla had suggested. After a few minutes, Tesla begged him to come down. “Not by a jugfull,” insisted Twain, apparently enjoying himself. When Tesla finally turned the machine off, Twain lurched forward looked at Tesla and pleadingly yelled: “Where is it?”

He was, of course, asking for direction to the toilet room. “Right over there,” Tesla responded chuckling. But Tesla knew he had done Twain a favor. “In less than two months, he regained his old vigor and ability of enjoying life to the fullest extent.”

Of course, Tesla never did patent or market a machine for such a specific purpose and Twain didn’t talk about it, so it’s mostly lost to time, unlike the photograph. Both men now have an important place in history and numerous books are written about them. Twain’s recollections are mostly in his own hand. But the story of Twain’s visit to Tesla’s lab and Twain’s resulting step on the oscillating platform is found in Tesla’s versions, not Twain’s.

Perhaps, as one Tesla biographer suggests, it was all a big practical joke, which certainly – and quite remarkably – turns the tables on both men’s reputations considering Twain was the humorist and Tesla the brain.

Despite this, and knowing the outcome, even if it was only intended for a laugh, both men were likely pleased with the results.

But for completely different reasons.

‘The Paramount Girl’ and the Road Trip to the Movies

By Ken Zurski

On October 19, 1915, Hollywood silent movie actress Anita King pulled into Times Square in New York City and became the first woman on record to drive a touring vehicle solo across the country.

She broke no speed record – 48 days – but was she really trying? Movie giant Paramount Studios sought publicity for the stunt and publicity is exactly what they got. The papers were all over it. “Colorful, convoluted and contradictory” is how one writer described King’s elaborate and perhaps embellished tales from the road.

But it was never boring.

King made stops at over a hundred Paramount theaters and graciously greeted well wishers along the way. But in between – and for most of the 3,000-plus mile journey – the 30-year-old, curly-haired blonde, still had to drive long stretches by herself, on paved and unpaved roads, and in all types of weather. In the Sierra Mountains, she recalled, a tramp tried to hitch a ride. “I wouldn’t permit myself to show how frightened I was,” King said. “I handed him a flask of whiskey I had in the car and told him to come to the theater where I was appearing the next night.” He did, according to King, bringing a bouquet of picked flowers with him.

Some of the reports were bleak.

King “wilted in the heat,” went one newspaper account.

“She was nearly a goner” read another.

Each story King told reporters seemed to be more extraordinary than the next. In one harrowing incident, just outside of Reno, the car’s tires became stuck in the mud. King spent hours trying to shovel them out, but got nowhere. Then suddenly, she was not alone. A “mad coyote” joined her company. “Gee it looked as big as a horse,” she explained. “I finally killed him, and knew nothing more until I was picked up by prospectors, who heard the shots of my gun.”

King was born to immigrant parents who settled in Michigan City, Indiana. Her father committed suicide in 1896 when she was 12 years old and only two years after that her mother succumbed to tuberculosis. King was a grief-stricken teenager and an orphan. She moved from Michigan City to Chicago where she found work as a model and actress. In 1908, at the age of 24, she traveled to California and became fascinated with motor vehicles. She competed in a few auto races but after an accident decided to concentrate on her acting career instead. She appeared in a couple of comedic films, bit parts really, but nothing star making.

That’s when she heard her boss, motion picture producer John L. Lasky, talking about the Lincoln Highway, the newly opened coast to coast route between San Francisco and New York City that ran through 13 states.

Although it was dedicated in 1913, the road was still a work in progress and Lasky said – perhaps jokingly – that it would be at least ten years before the highway would be in such shape that a lady could make the drive without difficulty.

King chimed in. She could drive a car and she could make the trip now. Seeing the promotional value in the stunt, Lasky was on board telling her he would pay for it and secure a major sponsorship with the Kissel Motor Car Co. for transportation, a machine built for endurance and advertised as “every inch a car” and an “all-year vehicle.” King’s job was to act like a “movie star” and in return, Lasky promised, he would make her one.

King was ecstatic.

Dubbed “The Paramount Girl,” in the papers, King drove the Kissel Kar with a “new set of Firestone tires,” another Lasky sponsor. “There will be nobody with her,” the Los Angeles Times reported, “her only companions will be a rifle and six shooter.”

The trip began appropriately in front of Lasky’s Paramount studios in Hollywood.

When she arrived in New York City, King received a hero’s welcome. She was the honored guest at a ceremonial dinner and shook hands with dignitaries. In typical fashion though, the city’s newspapers, while celebratory, were skeptical too. “Miss King, in spite of being on the road from September 1 to yesterday, had no marks of tan or sunburn,” the New York Sun questioned. King explained she used grease paint on her face all the time. “I was determined I wouldn’t come into New York City with a red nose,” she said.

King became a darling celebrity and a movie titled ”The Race” starring King and Victor Moore went immediately into production. It was released the following year.

Much to Lasky’s surprise, the film was a disappointment. It got poor reviews and ran for only a week. King’s true-life exploits on the road, as it turned out, just weren’t as interesting on the silver screen.

King however remembered the groundbreaking trip fondly. In an interview, she recalled meeting a young girl on the side of the road who had packed a bag and wanted to runaway with King to the movies. From the heart, King gave her a lesson in humility.

“I would give the world to have what you have right there in that home,” she said.

Then King got back in her car, waved goodbye to the little girl, and drove off to her next adventure.

The Legacy Of The Buffalo Is Recounted In Vastly Different Ways

By Ken Zurski

In Son of the Morning Star, Evan S. Connell’s brilliant but unconventional retelling of the life and death of George Armstrong Custer, a part of the author’s captivating account is the detailed descriptions of what it would have been like to live, explore and fight in the vast and mostly uncharted territory of the Western Plains.

A land that Custer among others were seeing for the first time.

Custer’s life, of course, ends in Montana at Little Bighorn. But in the context of his story, and examined in Connell’s book, is the role of the country’s most populated mammal at the time: the buffalo.

The human inhabitants had vastly differing opinions on the buffalo, both revered and reviled, but Connell wisely avoids a scurrilous debate. Instead, he gives a fascinating glimpse, based on good research and eyewitness accounts, on what it was like to see the massive herds up close and why they were ultimately decimated. The reasons were just as divided as cultures.

At first the descriptions were formidable. “Far and near the prairie was alive with Buffalo,” Francis Parkman, a writer, recalled after seeing the herds in 1846, “….the memory of which can quicken the pulse and stir the blood.”

Indeed Parkman was right about the prairie being “alive” with buffalo, but unfortunately there is no exact number of how many were in existence before the Calvary arrived. That’s because there was no way to survey the population at the time. Connell doesn’t speculate either, but based on recollections like Parkman’s, others have estimated from 30 million to perhaps as much as 75 million buffalo may have roamed the plains at some point, maybe even more.

“Like black spots dotting the distant swell,” Parkman continued, “now trampling by in ponderous columns filing in long lines, morning, noon, and night, to drink at the river – wading, plunging, and snorting in the water – climbing the muddy shores and staring with wild eyes at the passing canoes.”

The description of herd sizes is nearly incomprehensible. Col. Richard Irving Dodge reported that during a spring migration, buffalo would move north in a single column perhaps fifty miles wide. Dodge claims he was forced to climb Pawnee Rock (Kansas) to escape the migrating animals. When he looked across, the prairie was “covered with buffalo for ten miles in each direction.”

In 1806, Lewis and Clark, one of the earliest explorers to encounter the massive herds gave an ominous warning. “The moving multitude darkened the whole plains,” Clark relayed.

The sound of the migrating herd was just as impressive as the numbers. The bulky animals each weighed close to a ton each, so when they all galloped, the ground shook. “They made a roar like thunder,” wrote a first settler along the Arkansas River.

The large groupings, however, made it easier to strike them down. And when the killing started, it didn’t stop. In 1874, when Dodge returned to the prairie, he saw more hunters than buffalo. “Every approach of the herd to water was met with gunfire,” he recalled

Killing buffalo became a sport, even for foreigners. Connell reports that The London Times ran ad for a trip to Fort Collins and a chance to kill a buffalo for 50 guineas. Many gleefully went for the adventure, not the challenge. As Connell explains, English lords and ladies came to sit in covered wagons or railway carriages and fire at will. You couldn’t miss.

“Enterprising Yankees turned a profit collecting bones,” Connell wrote, explaining that it was the hide and bones and not the meat they were interested in. “Porous bones were shipped east to be ground as fertilizer; solid bones could be whittled into decorative trinkets – buttons, letter openers, pendants.”

Many settlers not knowing what else to do with a wayward buffalo grazing on their land, just shot it and left it for the wolves to feed. “The high plains stank with rotten meat” Dodge wrote.

“In just three years after the gun-toting Yankees arrived,” Connell soberly relates, “eight million buffalo were shot.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, they were nearly all gone.

The Native Americans killed buffalo too, but it was for survival, not sport. Nearly every part of the animal was used for food, medicine, clothing or tools. Even the tail made a good fly swatter. According to the Indians, the buffalo was the wisest and most powerful creature, in the physical sense, to walk the earth. Yet the Indians still played a part in the animal’s near extinction. Large fires were set by tribes in part to fell cottonwood trees and feed the bark to their horses. The massive infernos, some set one hundred miles wide, were necessary to clear land for new grass. Although no one is quite sure, thousands of buffalo and other animals surely perished in the process.

In contrast, Connell includes claims by early pioneers that the Indians were just as wasteful as the “white man” in killing the buffalo, leaving the dead carcasses where they lay, and extracting only the tongues to exchange for whiskey. These reports contradict that of agents stationed at reservations after government agreements were reached. James McLaughlin who was at Standing Rock in South Dakota helped organize mass buffalo killings, but only to stave off starvation, he claims.

Regardless, the difference in attitudes is what may have inflamed tensions between the “palefaces” and the natives.

Dodge claims the buffalo were shot because they were “the dullest creature of which I have any knowledge.” Dull meaning stupid in this sense. They would not run, Dodge purports. “Many would graze complacently while the rest of the herd was gunned down.” Dodge says his men would have to shout and wave their hats to drive the rest of the herd off.

So according to Dodge – and Connell’s book supports this – the buffalo were removed for meager profits and to get them out of the way of railways and advancing troops. This incensed the Indians, especially the Lakota, who in spite of their reliance on the buffalo, had more respect for the embattled “tatanka,” in a spiritual sense.

After all, in comparisons, they named their revered leaders and holy men after the beasts.

Custer knew one.

His name was Sitting Bull.

The Stinking Truth About The Phantom’s Opera House

By Ken Zurski

(Note: This story was inspired by a playbill for The Phantom of the Opera at Her Majesty’s Theater in London).

In Paris, around the mid 1800’s, a man named Eugene Belgrand was hired to overhaul a system of underground sewer tunnels that were built nearly five centuries before and while still in use, was in desperate need of repair.

The plan was to make the tunnels more functional in the era of modernized sanitation, which at the time, wasn’t very sanitized at all. That’s because in 19th century Paris, as in other large European cities, waste was still being tossed onto the street, washed away by the rain, and ending up in filthy rivers, like the Seine, where even the shamelessly rich and privileged who strolled the fancy stone walkways of its shore, were appalled.

The old tunnels could still be used, officials determined, but needed reinforcements and additions to be more effective. The French engineer’s task was simple: make it better.

That of course was the practical reason for the upgrade. The more emotional plea came from Parisons who were just plain sick of the consistently putrid smell and squalor conditions. Women especially complained that they were forced to carry parasols all the time for fear of being dumped on from windows above. So Belgrand reshaped the tunnel routes, put in more drains, built more aqueducts, and started treatment plants. Eventually, 2,100 km (1300 miles) of new pipes were installed and the Paris sewer system became the largest of its kind in the world.

But not necessarily the most reliable.

Many of the early tunnels were built tall and wide, but not designed for uniformity. The chutes weren’t long enough or sufficiently sloped enough to keep the flow moving. Victor Hugo in his 1862 novel Les Misérables called the Paris sewers a “colossal subterranean sponge.” Even improved, the waste would still back up and somebody – or something – had to unclog it. Workers would do their best to dislodge the muck first by hand – usually with a rake. When it was too deep, or wouldn’t budge, dredging boats were used with some success. But when a boat didn’t work, by far the most effective method was using the wooden ball.

Yes, a wooden ball.

The ball was around 5-feet in diameter and resembled a wrecking ball in size, but not nearly as heavy. Constructed out of wood and hollow inside the outside was reinforced with metal for more solidity.

Some mislabeled it an “iron ball,” assuming it was solid throughout, which if true would have been far too cumbersome to move. Several men with ropes could easily lift the wooden ball or pull it into position. With a push the ball was sent careening into a tunnel. (Think of a bowling ball rolling down an alley gutter – only on a much larger scale.)

A London society newsletter in 1887, praised its dependability: “As soon as it comes to a point where there is much solid matter in the sewer it is driven against the upper surface of the pipe and comes to a standstill. Meanwhile the current gathering strength behind it rushes with tremendous force below the ball carrying away all sediment or solid matter and leaving the course clear.” The ball worked well for a time, but eventually its effectiveness wasn’t enough. By the early 20th century, a more streamlined method was deployed that harnessed and released rain water. The increase in the current’s velocity would flush the obstruction away. “The rain which sullied the sewer before, now washes it,” Hugo declared.

The Paris tunnels are still in use today and tourists to the city can visit a museum dedicated to the centuries old system. Guided tours lead patrons through narrow stairwells and dank rooms as the sound of waste water is heard rushing through the tunnels below. Even the wooden balls are on display.

But the Paris tunnels have more history than just collecting and deporting sewerage

When the famous Paris Opera House was built in the 1870’s, architect Charles Garnier’s construction team ran into a problem. While digging the foundation wall, they hit an arm of the Seine, likely an extension of the tunnel system that led to the river. They tried to pump the water out but it kept coming back. So Garnier designed a way to collect the water in cisterns thereby creating an artificial lake nearly five stories beneath the stage.

It is in this “hidden lagoon” that author Gaston Leroux had an idea for a book that he claims was based on real events. In the story titled Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, a troubled soul named “Erik,” who is grossly disfigured, escapes to the catacombs and the lake below the Opera House. By banishing himself from society, “Erik” became a “ghostlike” figure until a sweet soprano’s voice lures him back to the theater’s upper works.

In the popular musical version that came out many years later, the “Phantom of the Opera” takes his unsuspecting love interest Christine on a gondola ride through the underground lake.

A scenario that if true, would be far less romantic than portrayed in the famous theatrical production.

Whether or not the lake was connected to the tunnels or ran directly from the Seine River, didn’t matter. The result would still be the same. Instead of being mesmerized by the experience as if in a fantasy world, in reality, the lovely Christine would likely be holding her nose, gagging, or worse.

Cue the music.

Why Did Americans Get Taller? The Evolution of Height Trends

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

If there is one distinctive feature about furniture in the early to mid 1800’s, especially the parlor chairs, it is the height of the legs. While many leg posts are decoratively ornate, they are also quite short, and certainly much lower than what is considered standard today.

The history of furniture is a bit sketchy on this dissimilarity. Style, fabrics and materials tend to dominate the evolution of furniture. But speculation is – backed up by good statistics – that we as humans were just smaller in height and therefore furniture was made to reflect that.

Basically the lower we stood, the lower we sat.

The Civil War is a good example of this height disparity.

Statistics were actually taken for large groups of men. For instance, in the 44th Massachusetts Infantry, of the 98 soldiers between the ages of 17 and 40, the average soldier’s height was 5-foot 7- inches. The shortest man in the regiment was 5-foot 3-inches and the tallest 6 -foot 1-inch. The most surprising stat is on the higher end where based on the average, very few men were six-feet and above and no one was more than one-inch over the six-foot threshold.

Today nearly 15-percent of all men are over six-feet tall, with the average height of a American male at 177 cm, or 5-feet 10-inches. The average height of an American women is 164 cm, or approximately 5-foot 4-inches tall. Only statistics based on race changes this slightly.

So why did we get taller? Evolution is the simple answer, but even that is convoluted, as development suggests a reversal in size. “The average population should have become shorter because the shorter individuals in the population were, from an evolutionary fitness perspective, more successful in passing on their genes,” wrote Scientific American in 1998. “But this did not happen. Instead, all segments of the population–rich and poor, from small and large families–increased in height.”

Scientists claim better nutrition especially in children is the reason we got taller since the rise in height began to take root in the later half of the 19th century when there was an emphasis on living longer. It has since leveled off.

But even as the Civil War suggests, while most men stood under 6-foot-tall, there were exceptions.

Like Abraham Lincoln. ‘

Standing at 6 ft 4 in, Lincoln towered over Civil War generals like Ulysses S. Grant, who was above average at height for the time at 5 ft 8 inches. Pictures confirm this discrepancy in height. The stovepipe hat certainly adds to Lincoln’s size, but there is no doubt the 16th President stood unusually high for his time.

This means Lincoln must have been an uncomfortable guest in most Victorian-style residences of the era where ceilings were built lower and door frames tighter. Except in his own home which was modified to accommodate his tallness, Lincoln did a lot of ducking.

But his biggest obstacle may have been trying to find a suitable place to sit.

However, one permanent seat, made of marble, is the perfect size.