History

The Legacy Of The Buffalo Is Recounted In Vastly Different Ways

By Ken Zurski

In Son of the Morning Star, Evan S. Connell’s brilliant but unconventional retelling of the life and death of George Armstrong Custer, a part of the author’s captivating account is the detailed descriptions of what it would have been like to live, explore and fight in the vast and mostly uncharted territory of the Western Plains.

A land that Custer among others were seeing for the first time.

Custer’s life, of course, ends in Montana at Little Bighorn. But in the context of his story, and examined in Connell’s book, is the role of the country’s most populated mammal at the time: the buffalo.

The human inhabitants had vastly differing opinions on the buffalo, both revered and reviled, but Connell wisely avoids a scurrilous debate. Instead, he gives a fascinating glimpse, based on good research and eyewitness accounts, on what it was like to see the massive herds up close and why they were ultimately decimated. The reasons were just as divided as cultures.

At first the descriptions were formidable. “Far and near the prairie was alive with Buffalo,” Francis Parkman, a writer, recalled after seeing the herds in 1846, “….the memory of which can quicken the pulse and stir the blood.”

Indeed Parkman was right about the prairie being “alive” with buffalo, but unfortunately there is no exact number of how many were in existence before the Calvary arrived. That’s because there was no way to survey the population at the time. Connell doesn’t speculate either, but based on recollections like Parkman’s, others have estimated from 30 million to perhaps as much as 75 million buffalo may have roamed the plains at some point, maybe even more.

“Like black spots dotting the distant swell,” Parkman continued, “now trampling by in ponderous columns filing in long lines, morning, noon, and night, to drink at the river – wading, plunging, and snorting in the water – climbing the muddy shores and staring with wild eyes at the passing canoes.”

The description of herd sizes is nearly incomprehensible. Col. Richard Irving Dodge reported that during a spring migration, buffalo would move north in a single column perhaps fifty miles wide. Dodge claims he was forced to climb Pawnee Rock (Kansas) to escape the migrating animals. When he looked across, the prairie was “covered with buffalo for ten miles in each direction.”

In 1806, Lewis and Clark, one of the earliest explorers to encounter the massive herds gave an ominous warning. “The moving multitude darkened the whole plains,” Clark relayed.

The sound of the migrating herd was just as impressive as the numbers. The bulky animals each weighed close to a ton each, so when they all galloped, the ground shook. “They made a roar like thunder,” wrote a first settler along the Arkansas River.

The large groupings, however, made it easier to strike them down. And when the killing started, it didn’t stop. In 1874, when Dodge returned to the prairie, he saw more hunters than buffalo. “Every approach of the herd to water was met with gunfire,” he recalled

Killing buffalo became a sport, even for foreigners. Connell reports that The London Times ran ad for a trip to Fort Collins and a chance to kill a buffalo for 50 guineas. Many gleefully went for the adventure, not the challenge. As Connell explains, English lords and ladies came to sit in covered wagons or railway carriages and fire at will. You couldn’t miss.

“Enterprising Yankees turned a profit collecting bones,” Connell wrote, explaining that it was the hide and bones and not the meat they were interested in. “Porous bones were shipped east to be ground as fertilizer; solid bones could be whittled into decorative trinkets – buttons, letter openers, pendants.”

Many settlers not knowing what else to do with a wayward buffalo grazing on their land, just shot it and left it for the wolves to feed. “The high plains stank with rotten meat” Dodge wrote.

“In just three years after the gun-toting Yankees arrived,” Connell soberly relates, “eight million buffalo were shot.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, they were nearly all gone.

The Native Americans killed buffalo too, but it was for survival, not sport. Nearly every part of the animal was used for food, medicine, clothing or tools. Even the tail made a good fly swatter. According to the Indians, the buffalo was the wisest and most powerful creature, in the physical sense, to walk the earth. Yet the Indians still played a part in the animal’s near extinction. Large fires were set by tribes in part to fell cottonwood trees and feed the bark to their horses. The massive infernos, some set one hundred miles wide, were necessary to clear land for new grass. Although no one is quite sure, thousands of buffalo and other animals surely perished in the process.

In contrast, Connell includes claims by early pioneers that the Indians were just as wasteful as the “white man” in killing the buffalo, leaving the dead carcasses where they lay, and extracting only the tongues to exchange for whiskey. These reports contradict that of agents stationed at reservations after government agreements were reached. James McLaughlin who was at Standing Rock in South Dakota helped organize mass buffalo killings, but only to stave off starvation, he claims.

Regardless, the difference in attitudes is what may have inflamed tensions between the “palefaces” and the natives.

Dodge claims the buffalo were shot because they were “the dullest creature of which I have any knowledge.” Dull meaning stupid in this sense. They would not run, Dodge purports. “Many would graze complacently while the rest of the herd was gunned down.” Dodge says his men would have to shout and wave their hats to drive the rest of the herd off.

So according to Dodge – and Connell’s book supports this – the buffalo were removed for meager profits and to get them out of the way of railways and advancing troops. This incensed the Indians, especially the Lakota, who in spite of their reliance on the buffalo, had more respect for the embattled “tatanka,” in a spiritual sense.

After all, in comparisons, they named their revered leaders and holy men after the beasts.

Custer knew one.

His name was Sitting Bull.

The Stinking Truth About The Phantom’s Opera House

By Ken Zurski

(Note: This story was inspired by a playbill for The Phantom of the Opera at Her Majesty’s Theater in London).

In Paris, around the mid 1800’s, a man named Eugene Belgrand was hired to overhaul a system of underground sewer tunnels that were built nearly five centuries before and while still in use, was in desperate need of repair.

The plan was to make the tunnels more functional in the era of modernized sanitation, which at the time, wasn’t very sanitized at all. That’s because in 19th century Paris, as in other large European cities, waste was still being tossed onto the street, washed away by the rain, and ending up in filthy rivers, like the Seine, where even the shamelessly rich and privileged who strolled the fancy stone walkways of its shore, were appalled.

The old tunnels could still be used, officials determined, but needed reinforcements and additions to be more effective. The French engineer’s task was simple: make it better.

That of course was the practical reason for the upgrade. The more emotional plea came from Parisons who were just plain sick of the consistently putrid smell and squalor conditions. Women especially complained that they were forced to carry parasols all the time for fear of being dumped on from windows above. So Belgrand reshaped the tunnel routes, put in more drains, built more aqueducts, and started treatment plants. Eventually, 2,100 km (1300 miles) of new pipes were installed and the Paris sewer system became the largest of its kind in the world.

But not necessarily the most reliable.

Many of the early tunnels were built tall and wide, but not designed for uniformity. The chutes weren’t long enough or sufficiently sloped enough to keep the flow moving. Victor Hugo in his 1862 novel Les Misérables called the Paris sewers a “colossal subterranean sponge.” Even improved, the waste would still back up and somebody – or something – had to unclog it. Workers would do their best to dislodge the muck first by hand – usually with a rake. When it was too deep, or wouldn’t budge, dredging boats were used with some success. But when a boat didn’t work, by far the most effective method was using the wooden ball.

Yes, a wooden ball.

The ball was around 5-feet in diameter and resembled a wrecking ball in size, but not nearly as heavy. Constructed out of wood and hollow inside the outside was reinforced with metal for more solidity.

Some mislabeled it an “iron ball,” assuming it was solid throughout, which if true would have been far too cumbersome to move. Several men with ropes could easily lift the wooden ball or pull it into position. With a push the ball was sent careening into a tunnel. (Think of a bowling ball rolling down an alley gutter – only on a much larger scale.)

A London society newsletter in 1887, praised its dependability: “As soon as it comes to a point where there is much solid matter in the sewer it is driven against the upper surface of the pipe and comes to a standstill. Meanwhile the current gathering strength behind it rushes with tremendous force below the ball carrying away all sediment or solid matter and leaving the course clear.” The ball worked well for a time, but eventually its effectiveness wasn’t enough. By the early 20th century, a more streamlined method was deployed that harnessed and released rain water. The increase in the current’s velocity would flush the obstruction away. “The rain which sullied the sewer before, now washes it,” Hugo declared.

The Paris tunnels are still in use today and tourists to the city can visit a museum dedicated to the centuries old system. Guided tours lead patrons through narrow stairwells and dank rooms as the sound of waste water is heard rushing through the tunnels below. Even the wooden balls are on display.

But the Paris tunnels have more history than just collecting and deporting sewerage

When the famous Paris Opera House was built in the 1870’s, architect Charles Garnier’s construction team ran into a problem. While digging the foundation wall, they hit an arm of the Seine, likely an extension of the tunnel system that led to the river. They tried to pump the water out but it kept coming back. So Garnier designed a way to collect the water in cisterns thereby creating an artificial lake nearly five stories beneath the stage.

It is in this “hidden lagoon” that author Gaston Leroux had an idea for a book that he claims was based on real events. In the story titled Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, a troubled soul named “Erik,” who is grossly disfigured, escapes to the catacombs and the lake below the Opera House. By banishing himself from society, “Erik” became a “ghostlike” figure until a sweet soprano’s voice lures him back to the theater’s upper works.

In the popular musical version that came out many years later, the “Phantom of the Opera” takes his unsuspecting love interest Christine on a gondola ride through the underground lake.

A scenario that if true, would be far less romantic than portrayed in the famous theatrical production.

Whether or not the lake was connected to the tunnels or ran directly from the Seine River, didn’t matter. The result would still be the same. Instead of being mesmerized by the experience as if in a fantasy world, in reality, the lovely Christine would likely be holding her nose, gagging, or worse.

Cue the music.

A Salute to the Long Play (LP) Microgroove Vinyl Record

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

In 1948, the LP (Long Play) microgroove vinyl record was introduced by Columbia Records for the sole purpose of playing more music on a phonograph or analog sound medium. Circular in shape like its predecessors, the LP was larger in diameter at 16-inches and turned at 33 1/3 revolutions per minute, much slower than previous versions.

The LP itself was designed to replace the 12-inch records being manufactured for RCA Victor player’s in the 1930’s. The smaller plates had tighter grooves and less background noise, but unpredictable sound clarity overall.

The larger LP’s were slow to catch on at first, representing only a slight percentage of sales for consumers who were accustomed to the smaller size, faster speeds (78 rpm) and shorter play time. But as home stereo systems improved, LP’s were streamlined back to 12-inches and quickly became the preferred choice of buyers.

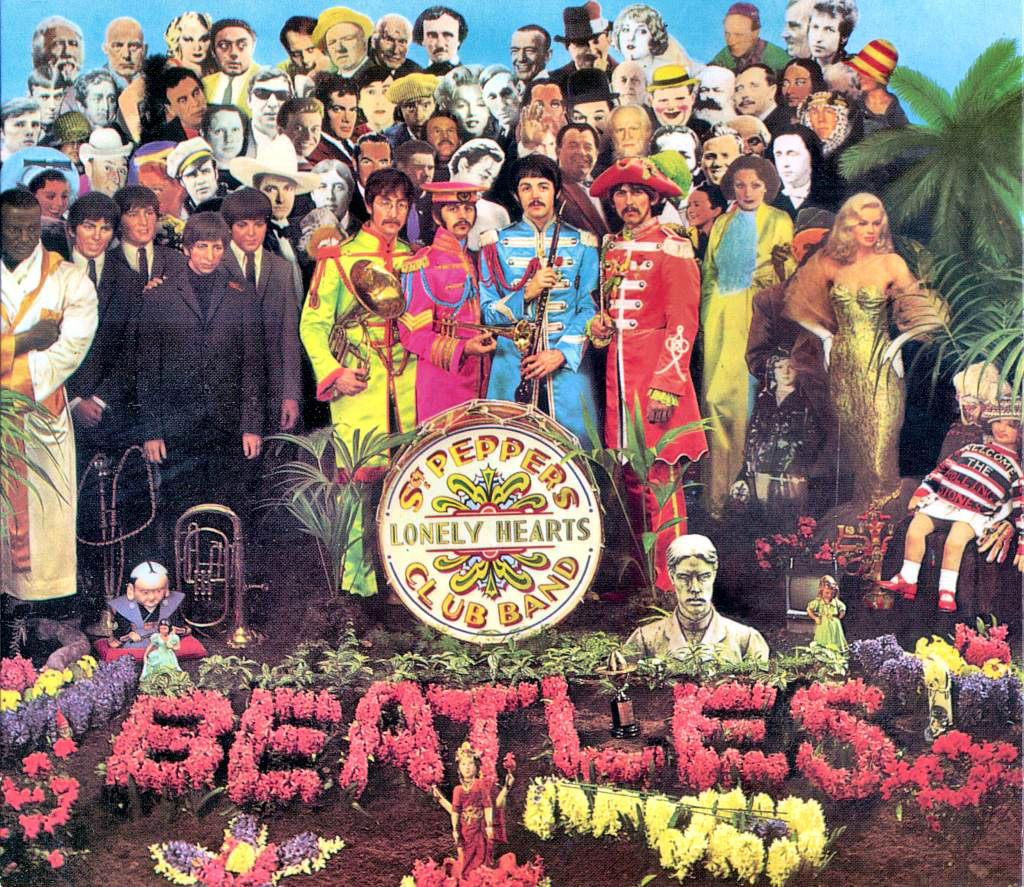

In the 1960’s and continuing into the 70’s, music artists such as the Beatles and Pink Floyd found a niche by exploiting the availability of time per LP side. They began experimenting with varying layered pieces of music, thereby making, marketing and selling albums with longer songs and conceptual themes. In some instances, two LP’s were included.

Then in the 1980’s, thanks to MTV and the demand to buy popular music, chain record stores opened in malls across America and record sales – included the smaller 45 rpm singles – continued to rise.

But it wouldn’t last.

Introduced in the mid 80’s, the new compact disc format (CD) was cheaper and less expensive to produce. The CD’s were about the same price as a vinyl album, but a CD player was costly. Eventually demand drove down the price and by the 1990’s, the age of the LP mostly disappeared. Mainstream record stores transitioned to stocking and selling only CD’s on their shelves.

Recently however, with no physical attributes attached to digital music, there’s been a surge in demand for vinyl. Newly pressed vinyl records of repackaged older and some newer music has become popular as turntables sales have increased as well. In fact according to the Recording Industry Association of America‘s midyear report for 2019, vinyl album sales may soon overtake sales of CD’s for the first time since 1986. This trend has prompted many new artists who have only produced music for the CD and digital markets to promote vinyl packaged versions of their albums as special editions.

According to c/net: “Just because vinyl may soon outpace CDs doesn’t mean music lovers are trading in their iTunes accounts for turntables. Streaming remains the most popular way to consume music, accounting for 80% of industry revenues, and growing 26%, to $4.3 billion, for the first half of 2019.”

Bu the LP just wont die. Today, original LP’s from the early 40’s to the mid 80’s are considered nostalgic and collectible. Many privately owned record shops, or independents as they are called, continue to thrive by specializing in rare or out of print editions. And online markets, swap meets and thrift stores are filled with opportunities to sell or purchase used albums.

A Salute to the Hand Salute – How Far Back Does it Go?

By Ken Zurski

In 1833, an Irish-born English artist named William Collins exhibited an oil on wood painting he appropriately titled, Rustic Civility. In the colorful image, three children are seen near a wooden gate that blocks the path of a dirt road. Collins shows the gate has been opened, presumably by the children. A boy is propped up against the open gate securing it’s place. Another smaller child cowers by the boy’s side. Yet another looks straight ahead from behind the gate.

But why and for whom did the children open the gate?

Well, that’s just a part of the painting’s mystique or as one art connoisseur wisely describes, “its puzzle.”

Upon closer inspection, however, the “puzzle” appears to be solved.

Most obvious is the shadow near the children’s feet. It is a partial outline of a horse and upon its back a rider in a brimmed hat. The children have opened the gate to make it easier for the rider, probably a stranger to them, to pass.

“People are amused at having to find out what is coming through the gate, which few do, till the shadow on the ground is pointed out to them,” the sixth Duke of Devonshire noted after buying the curious painting for his collection.

The work in some circles has been wrongly classified as a children’s picture. True, Collins would specialize in putting children in his paintings, but they were not specifically made for children. “Rustic” was part of his repertoire and a theme for several paintings including Rustic Hospitality, where friendly villagers welcome a wayward traveler who has stopped to rest near their cottage.

Today, most of Collins works are in London museums. His representations of English countryside charm in the early 19th century were very popular. Rustic Civility, however, seems to be remembered for a more significant and historical reasons. The young boy in the painting is holding his hand to his head in a gesture that closely resembles what we know today as a military salute.

A gesture not yet so easily defined at the time.

According to various sources, the origins of the hand salute goes back to medieval times when knights would salute one another by tipping their hats. Since their heads were covered with heavy and cumbersome armor, oftentimes they would just raise the visor in recognition.

In the Revolutionary War, British soldiers would remove or raise their hats in the presence of a ranking officer, an easy task since head gear at the time was used as decoration only and made of lighter material.

In subsequent wars, when soldier’s helmets became more protective the act of actually removing the head gear was too risky. A simple hand raise to the brow would suffice.

By the 20th century and during the two World Wars, saluting became more streamlined and distinctive, with the hands either palm out (the European version) or palm flat and down, the American preference.

Regardless of its history, Collins is credited at least with featuring a salute, albeit slyly, in his painting Rustic Civility. The boy appears to be “tugging his forelock,” an old-worldly expression of high regard and a gesture that suggests an early incarnation of the modern day hand to forehead signal.

This inclination of course is a matter of opinion. Perhaps, as others might suggest, the boy is just shading his eyes. After all, the location of the shadowed horse and rider puts the perspective of the sun’s light directly in the boy’s path. However, in close up, it does appear as though the boy is grabbing a lock of hair.

This clearly supports the salute theory.

Unfortunately, by the time any serious debate was raised, Collins, the artist, was dead.

So in historical context, let’s give the painter his due: To open a wooden gate while on horseback is a difficult thing to do. The children helped the man by opening the gate. The boy then saluted in deference – or civility as the title suggests.

A sign of a respect for an elder in need, Collins likely implied.

And respect is what the “salute” stands for today.

When The World Met Queen Marie of Romania

By Ken Zurski

In the summer of 1919, King Ferdinand of Romania sent his British born wife Queen Marie to Paris to attend the Treaty of Versailles, a historic meeting of allied leaders designed to form a peace treaty and draw a new map of Europe at the end of the First World War.

“My God, I simply went wherever they called me,” the Queen said, stating the obvious.

The glamorous Marie did more than just attend. She hobnobbed with the press, flirted with world leaders, including the Big Four (Italy, England, France and the U.S.), and although she had an important job to do for her country, found time to go on lavish shopping sprees too.

By the time the historic Treaty was over, everyone knew a little bit more about the outlandish Queen Marie. And thanks in part to her unorthodox efforts, Romania, at least on paper, had doubled in size.

Born into royalty as Princess Marie of Edinburgh in 1875 in Kent, England, Marie was the eldest daughter of her mother also named Marie, the only surviving child of Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and Alexander, the second son of Queen Victoria and a naval officer who moved the family extensively throughout her childhood. The Princess was a good catch, even as a youth, and gentleman came calling for her including a first cousin George (later George V of England) who professed his love for Marie, but was turned away.

In 1893, at the age of 18, Marie married Ferdinand, a third cousin, who by default, was the heir to the Romanian throne. King Carol I, Ferdinand’s uncle, and his wife had only one daughter so the succession fell to his brother Leopold, who renounced his rights in 1880. Leopold’s son did the same in 1886. So even before the turn of the 20th century, Ferdinand was the heir-presumptive. In 1916, when Carol died, Ferdinand became the King and Marie the Queen of Romania.

Marie was a different kind of Queen, less submissive and daringly independent. During the start of World War I, Marie spent time with the Red Cross in hospitals risking her own life in the disease filled tents. Although she was British born, she had great respect for the Romanian people and would venture into the countryside unaccompanied by guards. Many villagers crowded her in adulation; kissing her hands and falling down at her feet. “At first it was difficult unblushingly to accept such homage,” she wrote, “but little by little I got accustomed to these loyal manifestations; half humbled, half proud, I would advance amongst them, happy to be in their midst.”

In contrast to Marie’s adventurist spirit her husband, the King, was far less dynamic. Quiet and shy and as one writer described “stupid” too, Ferdinand’s most enduring feature was his ears which stuck out the sides of his head like a teddy bear. He said little and mattered even less.

Marie, however, was the complete opposite. Pretty and intelligent she spoke out when asked and seemed to have a good knowledge of foreign affairs. She also had little interest in being a committed wife. Blaming a loveless marriage, she was boldly unfaithful and found multiple lover’s in dashing figures like a Canadian millionaire miner from the Klondike. (In her later years, rumors abounded that one of her longstanding paramours, the nephew of Romania’a Foreign Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu, was the father of her children (six in all, three girls) except for the one that eventually became a bad King. That one was Ferdinand’s, went the biting accusation.)

In November of 1918, when war activities ended, Marie was the outspoken one not her husband. Sending her to the Treaty in Paris instead was an obvious choice for the King, if unprecedented.

So Marie went and brought her three daughters along with her. Together they shopped, dined and were generally the life of any party they attended. The Queen wore out those who tried to follow her. She charmed her way to negotiations and gained admirers along the way. “She really is an unusual woman and if she was not so simple you would think she was conceited,” chimed the British Ambassador to France. David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, was just as forthright: “{Marie] is a very naughty, but a very clever woman.” he professed. Edward House, an American diplomat and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s chief adviser on European diplomacy and politics, was even more complimentary, calling her, “one of the most delightful personalities of all the royal women I have met in the West.”

Instead of being intimidated, which many had predicted, Marie intimidated others with her saucy manners and speech. In one instance, she invited herself to lunch with President Wilson, then showed up fashionably late with an entourage of ten in tow. “I could see from the cut of the President’s jaw,” one guest noted, “that a slice of Romania was being looped off.”

According to reports, Marie dominated the conversation. “I have never heard a lady talk about such things.” remarked Wilson’s traveling doctor. ” I honestly do not know where to look I was so embarrassed.”

In the end, Romania grew in size and population. In fact, of all the contributors at the conference, Romania is widely considered to have picked up the greatest gains, including Transylvania which became – and still is – a part of “Greater Romania.” King Ferdinand could only wait for word back home. He sent letters of encouragement and advice to his wife, which she mostly ignored.

“I had given my country a living face,” she said about her visit.

(Sources: Paris 1919 by Margret MacMillian; My Country by Queen Marie; various internet articles)

The Bee Man

By Ken Zurski

When Amos Root was a boy growing up on a farm in Medina, Ohio, instead of helping his father with the chores he stuck by his mother’s side and tended to the garden instead.

Root was small in size (only five-foot-three as an adult) and prone to sickness. The garden work suited him just fine. But in his teens, for money, Root took up jewelry as a trade and became quite good at it.

Then in 1865, at the age of 26, he found his calling – bees.

Root had offered a man a dollar if he could round up a swarm of bees outside the doors of his jewelry store. The man did and Root was hooked. But Root didn’t want to just harvest bees, he wanted to study them.

Eventually his work led to a national trade journal titled Gleaning’s in Bee Culture. Bees became his business and profitable too, but Root had other interests as well, specifically mechanical things, like the automobile, a blessing for someone who hated cleaning up after the horse. “I do not like the smell of the stables,” he once wrote.

But the automobile was different. “It never gets tired; it gets there quicker than any horse can possibly do.”

He bought an Oldsmobile Runabout, “for less than a horse” he bragged, and happily drove it near his home. Then in September 1904, at the age of 69, Root took his longest trip yet, a nearly 400-mile journey to Dayton, Ohio. Root had heard a couple of “minister’s sons” were making great strides in aviation, so he wrote them and asked if he could take a look. His enthusiasm was evident.

He bought an Oldsmobile Runabout, “for less than a horse” he bragged, and happily drove it near his home. Then in September 1904, at the age of 69, Root took his longest trip yet, a nearly 400-mile journey to Dayton, Ohio. Root had heard a couple of “minister’s sons” were making great strides in aviation, so he wrote them and asked if he could take a look. His enthusiasm was evident.

The two brothers granted his wish, but only if he promised not to reveal any secrets. In August of 1904, Root set off for his first trip to Dayton and the next month did the same. The first visit he watched in awe, but revealed nothing. The second time he was given permission to write about what he had seen. It was the first time the Wright brothers and their flying machine appeared in print.

“My dear friends,” Root gleefully wrote in his bee publication, “I have a wonderful story to tell you. “

Uncovering Manson’s Teenage Years: The Peoria Connection

By Ken Zurski

Thanks to author Jeff Guinn’s biographical book of Charles Manson, titled Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson, a few more details emerge about the notorious killer’s time as a boy, his introduction to crime, early run-ins with the law, and in particular, his short but volatile stint in the nation’s heartland, specifically Peoria, Illinois.

Sometime in the late 1940’s, Guinn explains that Manson, or “Charlie” to his friends and family, and another boy named Blackie Nielson broke out of Boys Town in Omaha, Nebraska, stole a car and drove it to Peoria where Nielson’s uncle lived.

Manson was in Boy’s Town after failing to stay at another boy’s school in Terre Haute, Indiana. His mother Kathleen insisted Charlie go to a reform school while she served prison time for a bit role in an attempted robbery masterminded by her brother Luther, Charlie’s uncle.

In Terre Haute, Manson ran away and ended up in Indianapolis where he robbed a few dime stores. He needed the money to rent a room and hide. He pushed his luck though and got caught. The sympathetic judge went easy on young Charlie. “Erroneously assuming that the boy was Catholic,” Guinn writes, “the judge sends him to Boy’s Town, the most famous juvenile facility in America.”

That would straighten him out, the judge conferred. But it didn’t work. Boy’s Town had a reputation for turning wayward boys around, but it was no prison and security was lax. Manson and his new friend, Blackie, left the grounds, hotwired a car and hightailed it to Illinois.

What happens next is fragmentary. It’s probably why Guinn spends only a few paragraphs on it. In fact the word “Peoria” isn’t even listed in the book’s index. But Manson’s time in Peoria may be just as influential on the young boy’s life as his first arrest in Indianapolis. It’s also just as surprising, considering his age. After all he was only thirteen, according to Guinn.

Guinn writes that Charlie and Blackie set out to rob a few businesses in Peoria, including a grocery store. But these “knock offs” were different. Charlie had a gun. Even Guinn’s not sure how he got it, possibly stole it from Blackie’s uncle. But how is not as important as – why? In hindsight, it’s apparent the young boy was headed towards a more complicated life of crime – even murder. But instead of ripping off a few dinky stores just to get by like he did in Indianapolis, this time Manson armed with a weapon appeared to be doing it for fun. When Manson got caught again, a Peoria judge wasn’t so lenient. He sent Charlie to a hard core reform school in Plainfield, Indiana where adult supervisors were more like drill sergeants. The rest of Manson’s youth plays out similarly – bit robberies, run-ins with the law and eventually some prison time – until we get to the 1960’s and the unfortunate reasons why he is famous today.

But that was it for Manson’s time in Peoria.

Throughout the years, a few articles in the Peoria Journal Star bulletin the arrests but offer few details. Did Manson really try to rob the Chevrolet dealership on Main Street and jump into a squad car instead of a getaway car, as the paper claims? Heady stuff, for sure. But true?

Thanks to the efforts of Peoria Journal Star columnist Phil Luciano who in 1992 wrote a letter to Manson asking: What brought you to Peoria and what did you do here? Manson wrote back as he often did to reporter’s inquiries. His answers are lucid enough, but not very descriptive or specific. Manson recalls stealing some jewelry, putting it in a safe and dumping the safe over a bridge onto railroad tracks below. “Yeah, I did a lot of growing up in that town (Peoria),” he writes in the letter, “fast growing up.”

Manson’s other recollections of Peoria makes it sound like he was in town for months, if not years (Guinn’s book isn’t clear on this. Likely, it was only for a couple of weeks). Of course, for Manson, this comes nearly 50 years after the fact. A lot more scandalous and disturbing events took place in the man’s life since then, including the murder of actress Sharon Tate and four others on August 8th and 9th, 1969.

Guinn claims that his correspondence letters from Manson were mostly ramblings about how he had been wronged and not much else. “That’s all you need to know,” Manson curtly answered one letter after offering nothing substantial in return. Apparently he didn’t like books written about him.

Manson was sentenced to life for the Tate/LeBlanco murders, incarcerated in a California State Prison, frequently denied parole, and died on November 19, 2017 at the age of 83.

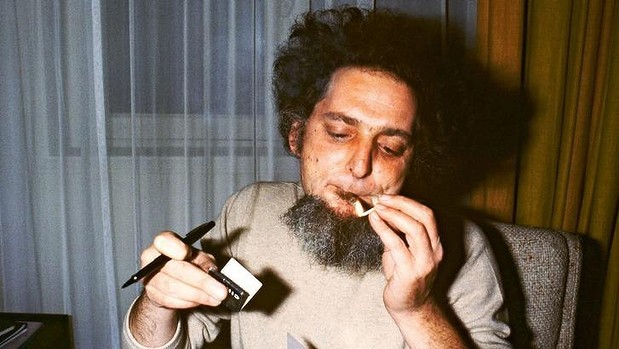

The cover of Guinn’s book shows a picture of a neatly dressed young man. He is smiling and seems content. Although his gaze is slightly off, there’s only a hint of the “crazy eyes” that his cousin’s claim Charlie possessed at times.

The more recognizable image of the convicted killer with tussled hippie-like long hair and a creepy blank stare would come later, when Manson was in his late 20’s and early thirties.

While in Illinois, Charlie was just a teenager.

- ← Previous

- 1

- …

- 5

- 6

- 7

- Next →