unrememebred history

General MacArthur and the Defining Days After Pearl Harbor

By Ken Zurski

In the book The General vs the President, author H.W. Brands examines the often tenuous but respectful relationship between General Douglas MacArthur and President Harry Truman.

Besides their differing personalities, in the public eye, the two men drew widely opposite impressions. Truman had unexpectedly assumed the presidency amidst doubts about his leadership and foreign policy experience while MacArthur was the beloved general of the Allied forces in the Pacific.

After World War II ended and when North Korea threatened South Korea, both men had vastly different views on how America should proceed.

Truman gave MacArthur leverage, but China was drawn into the conflict and the two world powers were nearly brought to the brink of a nuclear war. Truman relieved the popular general of his duties. “With deep regret I have concluded that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur is unable to give his wholehearted support to the policies of the United States Government and of the United Nations in matters pertaining to his official duties,” Truman announced at a press conference. That explosive missive is the basis of Brand’s book.

But Truman, as important as he was to ending the war, was just a senator from Missouri when President Franklin Roosevelt crossed ways with MacArthur.

That relationship nearly reached the boiling point in 1941, shortly after Japan attacked Pear Harbor.

It’s worth a closer look.

MacArthur who is in the Philippines at the time Pearl Harbor was attacked feared the American bases on the island would be next. He was right. The next day, December 8, Japan hit hard. MacArthur asked Roosevelt to immediately strike back. Force Russia to attack Japan, he pressed, before Japan can do more damage in the Philippines. Roosevelt ignored MacArthur’s plea and set his sights on Germany instead.

MacArthur rebutted. He supported a plan by Philippine President Manuel Quezon to broker a peace deal with Japan. It was the only way, MacArthur agreed, to avoid a “disastrous debacle.”

In retrospect, Brands assumes, MacArthur was abandoning the Philippines. But there were lives at stake. A defiant Roosevelt dismissed the peace deal. “American forces will continue to fly our flag in the Philippines,” the president commanded, “so long as there remains any possibility of resistance.”

Back home, MacArthur was being criticized for poor decision making.

Brands points out the there was a nine-hour window after the first dispatches were received that Japanese bombers were in the air. There was nothing anyone could do about the battleships in the Harbor; but in the Philippines, in hindsight, why didn’t MacArthur order the planes moved out of the way?

MacArthur blamed his subordinates and miscommunication. Nevertheless, half of MacArthur’s forces were decimated in the attack and the Philippine’s line of defense was greatly diminished.

It would get worse. The conquest of the Philippines by Japan is still considered one of the worst military defeats in U.S. history.

MacArthur endured attacks from Japan forces by hunkering down on the Bataan peninsula and Corregidor Island. “Help is on the way,” MacArthur told the men. “Thousands of troops and hundreds of planes are being dispatched” he continued, hoping to boost morale.

None of it was even being considered.

The only order coming from Roosevelt was getting his four-star general out of the islands before all hell broke loose. MacArthur had no recourse. It was an order, not a choice. He took the next plane out and flew to Australia where he was to organize the counter offensive against Japan and pave the way to his own interminable place in American history. Roosevelt would later praise his departure, but MacArthur felt like he was abandoning his post.

Before boarding he told the troops, “I shall return.”

When MacArthur did return three years later he was hailed as a hero. “Though not by American soldiers he left behind [in the Philippines],” Brands writes in the book.

Winston Churchill, The Boers War and the Invasion of the ‘Body Snatchers’

By Ken Zurski

In the book Hero of the Empire, author Candice Millard explores the military service of a young Winston Churchill and the future Prime Minister of England’s exploits in the Boers War, a devastating conflict against the fiercely independent South African Republic of Transvall, or Boers, that’s as much a part of British history as the two subsequent World Wars.

In 1899, Churchill was in his twenties and officially not a soldier, but a correspondent for the Morning Post. However, he bravely and willingly fought alongside his fellow countrymen. As Millard captures vividly in her book, when a British armored train was ambushed, Churchill fought back, was captured, imprisoned, managed to escape, and traversed hundreds of miles of enemy territory to freedom. He then returned and resumed his duties in the war. Millard’s expert narrative paints the young Churchill as a man of great strength, determination and steadfast loyalty.

The same attributes can also be applied to another famous figure in history who did not fight like Churchill, but bravely dodged the bullets of the Boers to do a thankless and daring task. His contribution is touched on briefly in the book, but is worth noting here as an example of a man whose legacy of peace and non-violence includes the brutal reality of warfare.

In stark contrast to Churchill’s call to arms, this figure refused to pick up a weapon or engage in hand to hand combat. His Hindu faith prevented that, but his desire for justice could not be suppressed. He was an Indian-born lawyer in a country under the flag of the British Empire who went to South Africa to defend his people from cruelty imposed by the Boers. When war broke out, he wanted to contribute, along with other persecuted Hindu followers.

But how?

So he asked the British government if he could put together a team of men to perform the incessant task of removing bodies, dead or wounded, from the heat of battle. The government approved the request, but made it clear that the men were under no obligation or safeguards from the British Army. The decision to risk their own lives in order to save others was theirs and theirs alone.

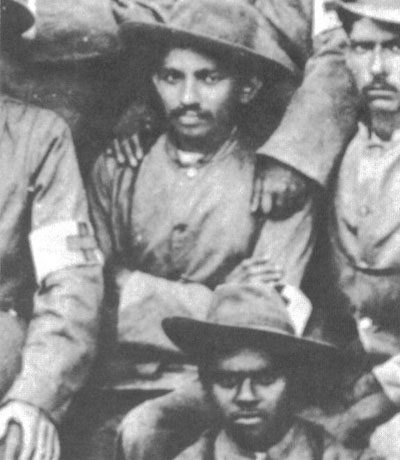

“Body snatchers,” was the term used by British troops to describe the men who retrieved “not just bodies from the battlefield, they hoped, but young men from the jaws of death,” Millard writes. The “body snatchers” wore wide brim hats and simple loose fitting khaki uniforms and were distinguished by “a white band with a red cross on it wrapped around their left arms.”

Their efforts were lauded by superiors and observers alike. “Anywhere among the shell fire, you could see them kneeling and performing little quick operations that required deftness and steadiness of hand,” wrote John Black Atkins a reporter for the Manchester Guardian.

By now you may discern that the person who assembled this unusual band of brave men is important to history. Millard doesn’t hold anyone in suspense.

The man was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi whose place in history as the influential Indian civil rights leader was just beginning to emerge.

When war broke out, Gandhi, who was 31 at the time, wanted to disprove stereotypes that Hindus were unfit for battlefield service.

“Although his convictions would not allow him to fight,” Millard writes, “he had gathered together more than a thousand men to form a corps of stretcher bearers.”

Later in his autobiography, Gandhi would recall his non-violent role in the Boers War.

“Our humble work was at the moment much praised, and the Indians’ prestige was enhanced,” he wrote.

“We had no hesitation.”

(Sources: Hero of the Empire by Candace Millard; The Story of My Life by M.K. Gandhi)

The Legacy of Perry Como: Christmas Crooner and Family-Friendly Performer

By Ken Zurski

Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television special and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time.

That said he may have been the most misunderstood as well.

Como was a one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced his craft incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week. Even Perry was surprised by the remuneration. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the town’s perceived association with mobsters and legalized prostitution, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduce his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually standing backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many wondered how much of it was real. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for 46 consecutive years ending in 1994, seven years before his death in 2001 at the age of 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)

There Is An Artist Behind The Iconic ‘Partridge Family’ Bus

By Ken Zurski

Painter Piet Mondrian, born in 1872, was an important leader in the development of modern abstract art and a major exponent of the Dutch abstract art movement known as De Stijl (“The Style”).

Mondrian used the simplest combinations of straight lines, right angles, primary colors, and black, white, and gray in his paintings.

According to one art historian: “The resulting works possess an extreme formal purity that embodies the artist’s spiritual belief in a harmonious cosmos.”

Mondrian who died in 1944 probably would never have imagined that his well-known artistic style would be the inspiration for a popular 1970’s television show called “The Partridge Family.”

Mondrian’s apparent contribution to the show was the exterior paint job of a school bus used by the fictional – but conventional – family of traveling musicians and singers. Mondrian’s style was on full display, seemingly based on one of his paintings.

The bus became the family’s trademark.

From Yahoo Answers: “Although the exterior paint job was arguably based on Mondrian’s Composizione 1921, it was never explained in the show why this middle class family from Southern California chose Dutch proto-modernism exterior paint, rather than the traditional school bus yellow.”

“The Partridge Family” ran on ABC television from September 25, 1970, until it ended on March 23, 1974. It would find an appreciate and loyal audience in syndication for years. Apparently the bus wasn’t so fortunate. As the story goes, after the show ended, the bus was sold several times until it was found abandoned in a parking lot at Lucy’s Tacos In East Los Angeles.

It was reportedly junked in 1987.

(Some text reprinted from Britannica.com and other internet sources)

Ken Zurski’s book “Unremembered: Tales of the Nearly Famous and the Not Quite Forgotten is available now http://a.co/d/hemqBno

The Split Thanksgiving Year: How FDR Altered The Holiday for Retail Recovery

By Ken Zurski

In September of 1939, Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a presidential proclamation to move Thanksgiving one week earlier, to November 23, the fourth Thursday of the month, rather than the traditional last Thursday of the month, where it had been observed since the Civil War.

That year, the last Thursday of November fell on the 30th, the fifth week and final day of the month. That was considered a late start to the shopping season. The Retail Dry Goods Association, a group that represented merchants who were already reeling from the Great Depression, went to Commerce Secretary Harry Hopkins who went to Roosevelt.

Help the retailers, Hopkins pleaded.

Roosevelt listened. He was trying to fix the economy not break it.

Thanksgiving would be celebrated one week earlier, he announced.

Apparently, the move was within his presidential powers since no precedent on the date was set. Thanksgiving, the day, was not federally mandated and the actual date had been moved before. Many states, however, balked at Roosevelt’s plan. Schools were scheduled off on the original Thanksgiving date and a host of other events like football games, both at the local and college level, would have to be cancelled or moved.

One irate coach threatened to vote “Republican” if Roosevelt interfered with his team’s game. Others at the government level were similarly upset. “Merchants or no merchants, I see no reason for changing it,” chirped an official from the opposing state of Massachusetts.

In contrast, Illinois Governor Henry Horner echoed the sentiments of those who may not have agreed with the president’s switch, but dutifully followed orders.

“I shall issue a formal proclamation fixing the date of Thanksgiving hoping there will be uniformity in the observance of that important day,” he declared, steadfastly in the president’s corner.

Horner was a Democrat and across the country opinions about the change were similarly split down party line: 22 states were for it; 23 against and 3 went with both dates.

In jest, Atlantic City Mayor Thomas Taggart, a Republican, dubbed the early date, “Franksgiving.” Others called it “Roosevelt’s Thanksgiving” or “Roosevelt’s hangover Thanksgiving Day.” More politically, some dubbed it “Democratic Thanksgiving Day” and the following Thursday as “Republican Day.” One observer noted, “This country is so divided it can’t even agree on a day of Thanksgiving.”

In some Midwestern states, especially among farmers, the controversy was irrelevant thanks to a bountiful harvest. “This year the crops certainly justified Thanksgiving, even justified two,” reported the Omaha-World Herald.

Roosevelt made the change official for the succeeding two years ’40 & ’41, since Thursday would fall late in the calendar both times. Then in 1941 The Wall Street Journal released data that showed no change in holiday retail sales when Thanksgiving fell earlier in the month. Roosevelt acknowledged the apparent miscalculation.

However, due to the uproar, later that year, Congress approved a joint resolution making Thanksgiving a federal holiday to be held on the fourth Thursday of the month, regardless of how many weeks were in November.

On December 26, 1941, Roosevelt signed it into law.

Roosevelt vs. Supreme Court: A Battle for Power

By Ken Zurski

On February 5, 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced his intention to expand the Supreme Court to as many as 15 justices. The move was clearly a political one. Roosevelt was trying to “pack” the court and in turn make the nation’s highest court a completely liberal entity. Republicans cried foul.

Roosevelt didn’t care what his opponents thought. He embraced the criticism and mostly ignored it. Although politically it was still a hot button issue, his New Deal policies had earned public acceptance, even praise. The high court, however, was another matter. They had previously struck down several key pieces of his legislation on the grounds that the laws delegated an unconstitutional amount of authority in government, specifically the executive branch, but especially the office of the president.

Roosevelt won the 1936 election in a landslide and was feeling a bit emboldened. If he could pack the court, he could win a majority every time. By constitutional law, Roosevelt couldn’t force any justice out, but he could offer an incentive to leave. So the president proposed legislation which in essence asked current Supreme Court justices to retire at age 70 with full pay or be appointed an “assistant” with full voting rights, effectively adding a new justice each time.

This initiative would directly affect 75-year-old Chief Justice, Charles Evan Hughes, a Republican from New York and a former nominee for president in 1916 who narrowly lost to incumbent Woodrow Wilson. Hughes resigned his post as a Supreme Court Justice to run for president, then served as Secretary of State under the Harding administration. In 1930, he was nominated by Herbert Hoover to return to the high court as Chief Justice. Hughes had sworn in Roosevelt twice. Now he was being asked by the president to give up his post or, under Roosevelt’s plan, give the president the power to appoint another justice.

In May of 1937, however, Roosevelt realized his “court packing” idea was wholly unnecessary. In an unexpected role of reversal, two justices, including Hughes, jumped over to the liberal side of the argument and by a narrow majority upheld as constitutional the National Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act, two of the administration’s coveted policies. Roosevelt never brought up the issue of court size again.

But his power move didn’t sit well with the press.

Newspaper editorials criticized him for it and the public’s favor he had enjoyed after two big electoral victories was waning. He was a lame duck president finishing out his second term. Then Germany invaded Poland. Roosevelt’s steady leadership was lauded in a world at war.

In 1940, he ran for an unprecedented third term and won easily.

The following year, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Dying For King, Country and Cloves

By Ken Zurski

In 1517, King Charles I of Spain, who had just assumed the throne at the tender age of eighteen, was approached by Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer who came to the young King after being rejected by his own country. Magellan made Charles an offer. Let him sail around the world and in the process find a direct route to Indonesia and the Spice Islands, once successfully navigated by Christopher Columbus.

Charles found Magellan’s plan intriguing.

Columbus’s four voyages for Spain, among other revelations, claimed new lands and precious spices like cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves which grew in abundance on the elusive islands. If Magellan could find a way to get the spices back to Charles, Spain would reap the rewards and rule the spice trade.

Charles wholeheartedly approved the voyage and ordered five ships and a crew of nearly 300 men.

In 1519, Magellan set sail from Seville.

Four years later, limping back to port, only one ship named Victoria returned. Every other ship was lost including most of the men. Even Magellan was gone, hacked to death on April 27, 1521 after a fierce battle with a native tribe.

Despite this, the King was pleased.

The tragic news of the lost ships and crew was irrelevant. The Victoria came back with a cargo of 381 sacks of cloves, the most coveted of all spices. “No cloves are grown in the world except the five mountains of those five islands,” explained the ship’s diarist.

Charles questioned the returning men on claims of a mutiny and other charges of debauchery, but it didn’t matter.

He paid the royal stipends to survivors, basked in his clove treasure, and set in motion plans to put another crew back en route to the islands.

The Out of This World Voice of Loulie Jean Norman

By Ken Zurski

Singer Loulie Jean Norman may not be a household name, but her voice is an unmistakable part of television history. More on that in a moment. First a little background.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1913, Norman soon discovered a knack for singing. She was uniquely talented as a coloratura soprano, a vocal range most commonly suited for opera. Unlike counterparts like stage star Maria Callas, however, Norman took her gift to radio instead.

It was the 1930’s, and radio was just starting to emerge as an entertainment force. Norman was in her twenties at the time. Her voice and beauty were being noticed. So she moved from Birmingham to New York City to jump start her career. Modeling jobs paid the bills at first, but singing was her passion.

She eventually got bit parts in singing ensembles on several musical variety shows including one with Bing Crosby who would signal her out several times for her solo passages. Norman provided studio background vocals to hitmakers like Sam Cooke, Frank Sinatra, Mel Torme and Elvis Presley. On TV, she appeared on the Dinah Shore Show, with Dean Martin, and as a back-up on Carol Burnett’s popular variety program.

“When you sang,” a colleague once told Norman, “it was the angels [voice].”

But her most influential and unaccredited contribution is truly out of this world.

In 1964, when television producer Gene Roddenberry introduced a new space serial he asked a friend Jerry Goldsmith to write the theme music. Goldsmith was too busy but enlisted fellow composer and collaborator Alexander Courage, who was said to be no fan of the science fiction genre, but drew inspiration from a song he heard on the radio titled “Beyond the Blue Horizon, ” which was featured in the 1930 movie “Monte Carlo” and sung by actress Jeannette McDonald, a soprano.

Courage wrote the theme for Star Trek the TV series.

Roddenberry heard the music and for reasons some explain were financially motivated, wrote lyrics for the tune. “Hey, I have to get some money somewhere,” Roddenberry reportedly said. “I’m sure not going to get it out of the profits of Star Trek.”

In 1999, Snopes.com confirmed there were Star Trek lyrics and debunked the theory that they (unearthed here) were ever used in the TV show’s theme.

Beyond

The rim of the star-light

My love

Is wand’ring in star-flight

I know

He’ll find in star-clustered reaches

Love,

Strange love a star woman teaches.

I know

His journey ends never

His star trek

Will go on forever.

But tell him

While he wanders his starry sea

Remember, remember me.

Courage was surprised – and perhaps, a bit offended – by Roddenberry’s lyrical contribution. He had included a voice in his recording, but no words. In the end, as Snopes reported, the lyrics were never used.

The choice of a singer was another matter. Courage picked someone similar to MacDonald, who ironically died the year the theme was written. It was Loulie Jean Norman. At the time, Norman was known for her studio work. Plus, she wasn’t a big enough star to turn down such an offer. Norman had the range Courage needed to make the tune work.

Star Trek: The Original Series ran for three seasons and 79 episodes. In the third and final year, despite a growing fan base, Roddenberry was hopelessly fighting low ratings, high production costs, and threats from the network to cancel.

He reportedly couldn’t pay Norman her royalty cut that year.

So after the second season, the theme was re-recording without the vocals.

Norman continued to do studio work, mostly backing vocals for songs like The Tokens version of The Lion Sleeps Tonight. The papers called Norman “the invisible soprano” for the work behind the scenes. “You’ve heard the voice, even if you’ve never heard the name.”

Even though fame eluded her, Norman acknowledged she would have been uncomfortable with it. “The reason why I didn’t care about being a star is because I saw what happened to stars,” she said in 1995. “I was close enough to see that they were not very happy.”

Norman died in August of 2005 at the age of 92.

Her obituary mentioned that unrecognized role.

“A voice heard around the world,” it read, “in the wordless, Star Trek theme.

The American-Made Safe That Survived Hiroshima

By Ken Zurski

In 1946, a U.S. Army Lieutenant surveying damage left by the massive explosion of the first atomic bomb in Hiroshima a year earlier, sent a letter to a safe-making company back in America. “I found in one of three structures standing, four large vaults built by the Mosler Safe Co. of Hamilton, Ohio,” he explained. “The vaults were entirely intact and except for the exterior being burned and rusted there was no damage.”

Two other vaults he added, made by a Toyko, Japan company, were completely destroyed.

The two-story Teikou Bank built in 1925 was close to the hypocenter of the blast. Made of steel and concrete, the building crumpled from the inside, cracking the exterior and tearing the cement floor to bits. Nearly two dozen employees were in side at the time. None survived.

But the bank vaults did.

This was reassuring news at least to bank executives back in the States.

At the time there was a heightened sense of security against attacks on American soil. Many banks advertised that valuables were better protected because they used Mosler safes.

Even the U.S government chimed in. Mosler was awarded a lucrative contract and eventually built a 25-ton blast door vault in West Virginia mountainside bunker used to hide classified and historical documents.

Then five years after the attack, Mosler received another letter.

This time it was from the manager of the newly rebuilt Teikou bank in Hiroshima. “Your products are admired,” he praised, “for being stronger than the atomic bomb.

“As you know in 1945 the Atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, and the whole city was destroyed and thousands of citizens lost their precious lives. And our building, the best artistic one in Hiroshima, was also destroyed. However it was our great luck to find that though the surface of the vault doors was heavily damaged, its contents were not affected at all and the cash and important documents were perfectly saved.”

In the late 1950’s, to recreate the same show of strength displayed in Hiroshima, Mosler took their products to the Yucca Flats nuclear testing grounds in the Nevada desert. They placed a Century steel door and concrete vault with various contents in the blast zone.

Once again the vault survived intact.