American history

How An Insane Asylum May Have Inspired the Iconic Twin Spires of Churchill Downs

By Ken Zurski

In 1794 a man named Isaac Hite, a Virginia Militia Officer, came to the Kentucky frontier with other surveyors to stake claim on scenic tracts of land given to them for fighting in the French and Indian War. They founded the properties as promised, but also encountered more Indians. And so in his newly adopted home now known as Anchorage, just outside of Louisville, Hite was killed by the hostile natives.

Or was he?

The introduction of a book containing Hite’s personal journal disputes claims he was struck down, but rather died from “natural causes,” at the age of 41. His companions, the book asserts, “had died years before, and violently, while taking Kentucky and holding it against the Indians.” One theory is that Hite was injured by Indians and later died from his wounds. But how he died isn’t as important as what he left behind. A parcel of land where he settled, started a family, and ran a mill and tannery.

Through the years, and for many generations, Hite’s descendants tended the land known as Fountain Bleu and an estate they dubbed Cave Springs Plantation. Then in 1869, the family sold the parcel to the State of Kentucky. The reason the state wanted it was explicit: open a new government institution for troubled youths near its largest city.

The rural, secluded site of Hite’s Cave Springs was the perfect setting for such a facility. Originally known as the “Home for Delinquents at Lakeland,” it was named after the path that led to it’s front gate, Lakeland Drive. It was converted – or just transformed – into a mental hospital in 1900 and renamed to reflect the often misunderstood and misdiagnosed residents who inhabited its 192 beds. “The Central Kentucky Lunatic Asylum,” as it was now called, became the state’s fourth facility for such a purpose.

As with any institution for the mentally challenged, in the early 20th century, the day-to-day operations were marred by allegations of abuse, malfeasance and deaths. Massive overcrowding was reported in the mid 1900’s and in 1943 the state grand jury found the asylum was committing people that were neither insane nor psychotic. One man was reportedly admitted for simply spitting in a courtroom. While the scientific merits of electric shock therapy and lobotomies were morally judged, the reports of fires, murders, and multiple escapes at the facility consistently filled the newspapers. It was a horror show.

Since many died on the grounds, many were buried there too. So stories of ghosts and haunted spirits are attributed to the site. “Have the mournful souls that died at Central State remained at the only home most of them ever knew?” a local ghost hunter asked.

The grounds, however, are also tied to the storied history of the Louisville underground. Literally, a series of caves and tunnels used before prohibition to move shipments – perhaps contraband during the Civil War – from the river docks to downtown buildings. Since a small cave existed before a tunnel was added, Hite was probably the first to discover the hole through the rock on his newly claimed property. Later after the state took over, the cave was reinforced with brick walls and pillars and used as cold storage mostly for perishable items like large cans of sauerkraut. The inside was reportedly lined with so many sauerkraut cans it was given a name by the locals: Sauerkraut Cave.

In the back of the cave a tunnel was built which has its own back door, so there was a natural entryway and a man made exit. Many morose stories about the lunatic asylum involve Sauerkraut Cave, including tales of residents who may have used it as an escape route or more graphic reports of pregnant patients who went there to give birth and abandon their babies. Those who visit the site today say without lights the cave would have been too dark and too flooded to navigate. Still, desperate patients may have drowned or froze to death trying.

Regardless of how many people perished on site or off, the general scientific worth of the experiments, and the ghastly stories that followed, the building itself was considered a architectural wonder at the time it was built.

Looking like a medieval castle in the front, the three story structure with wing additions on each side was made of solid red brick with stone trim. The small pane windows in the main building had segmental arches with brick molding and the facade was highlighted by a columned porch and railing. On the side of the main building is two identical towers, shooting high into the air and inspired by the Tudor revival style used in its original design. It quickly became one of the Louisville area’s most distinctive and important buildings when it opened its doors in 1869. By the time it came down, in the late 20th century, it had represented something else entirely.

But it’s legacy may be more lasting than you think.

Enter Joseph Dominic Baldez.

Baldez wasn’t even born yet when the asylum building was built, but eventually worked for the firm that created it. D.X Murphy & Bros was an offshoot of another firm established by Harry Whitestone. In the 1850’s. Whitestone, an Irish immigrant, designed some of the city’s elaborate homes, hotels and hospitals, including the Home for Delinquents on Lakeland Drive. When Whitestone retired in 1881, his top assistant Dennis Xavier (D.X.) Murphy took over the business. Baldez began working for Murphy at the age 20.

In 1894, Baldez, a native of Louisville and a a self-effacing, self-taught draftsman, started work on a project at the area’s racetrack known as Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby, the prestigious race for three-year-old thoroughbreds held every year at the beginning of May.

For 20 years since the track was built, the seating had been on the backstretch, facing west, a mistake, since the late afternoon sun would be directly in spectators eyes. So a new larger structure was planned on the other side, facing east, or directly near the one-eighth pole on the stretch. The D.X. Murphy firm was hired and the young Baldez, at 24, was commissioned to design the new stands. He went to work constructing a 250-foot long slanted seating area of vitrified brick, steel and stone with a back entrance wall lobby which on its own was not only fancy and stylish, but efficient too. It was graciously received: “The new grandstand is simply a thing of beauty,” raved the Louisville Commercial. The new grandstand included a “separate ladies section” and “toilet rooms,” the paper noted.

The Courier-Journal also chimed in: “With its monogram, keystone and other ornate architecture, it will compare favorably with any of the most pretentious office buildings or business structures on the prominent thoroughfares.”

Then there are the candles on the birthday cake, so to speak.

The Twin Spires.

Whether Baldez was asked to include it, or came up with the idea on his own is unclear. His diagrams clearly show what he intended to do: put one large spire on either side of the grandstand for ornamental decoration. Each spire would be 12 feet wide, 55 feet tall, and sit 134 feet apart from center to center. The base shape was octagonal for strength and surrounded by eight rounded windows which were designed to stay open (although later were glassed over to keep birds out). Above the windows was a decorative Feur-de-lis, or a “flower lily” shape, flanked by two roses which were decorative rather than symbolic since the race didn’t become the “Run for the Roses” until the late 20th Century.

Although others, like the track president at the time Col. Matt J. Winn, greatly admired the spires, Baldez was indifferent about his work. “They aren’t any architectural triumph,” he argued. “But are nicely proportioned.”

Although no one can be absolutely certain, and little about Baldez is known other than his designs, the building which housed the mental patients on Lakeland Drive on the former property of one of its first residents may have sparked the idea for the Twin Spires at Churchill Downs. The comparisons are justifiable. Both have large steeples, two in fact, and the tops of each are similar in design. Plus, Baldez knew the asylum building well by working at the firm that built it.

Perhaps as some suggest, the name Churchill Downs was also an inspiration for Baldez’s “steeples.” Churchill, however, was not a religious connotation, but the surname of the original owners John and Henry Churchill who leased the land to their cousin Colonel Meriwether Lewis Clark who subsequently built the track on the property.

Unfortunately, only pictures can tell the story now. The original asylum building was torn down in 1996 to make way for expansion. The Sauerkraut Cave is still there , but only as a curiosity. It’s entrance is marred by graffiti and only the brave – or crazy – dare enter it today. Other than the cemetery, the cave is the last vestige of the old grounds.

Baldez never told anyone what drew his interest in adding the adornment to the roof of Churchill Downs, but he gets credit for a lasting legacy, not only to horseracing, but to American culture in general.

Col. Winn knew it. “Joe, when you die, there’s one monument that will never be taken down,” he reportedly told Baldez.

He was talking about those famous Twin Spires.

The Legacy Of The Buffalo Is Recounted In Vastly Different Ways

By Ken Zurski

In Son of the Morning Star, Evan S. Connell’s brilliant but unconventional retelling of the life and death of George Armstrong Custer, a part of the author’s captivating account is the detailed descriptions of what it would have been like to live, explore and fight in the vast and mostly uncharted territory of the Western Plains.

A land that Custer among others were seeing for the first time.

Custer’s life, of course, ends in Montana at Little Bighorn. But in the context of his story, and examined in Connell’s book, is the role of the country’s most populated mammal at the time: the buffalo.

The human inhabitants had vastly differing opinions on the buffalo, both revered and reviled, but Connell wisely avoids a scurrilous debate. Instead, he gives a fascinating glimpse, based on good research and eyewitness accounts, on what it was like to see the massive herds up close and why they were ultimately decimated. The reasons were just as divided as cultures.

At first the descriptions were formidable. “Far and near the prairie was alive with Buffalo,” Francis Parkman, a writer, recalled after seeing the herds in 1846, “….the memory of which can quicken the pulse and stir the blood.”

Indeed Parkman was right about the prairie being “alive” with buffalo, but unfortunately there is no exact number of how many were in existence before the Calvary arrived. That’s because there was no way to survey the population at the time. Connell doesn’t speculate either, but based on recollections like Parkman’s, others have estimated from 30 million to perhaps as much as 75 million buffalo may have roamed the plains at some point, maybe even more.

“Like black spots dotting the distant swell,” Parkman continued, “now trampling by in ponderous columns filing in long lines, morning, noon, and night, to drink at the river – wading, plunging, and snorting in the water – climbing the muddy shores and staring with wild eyes at the passing canoes.”

The description of herd sizes is nearly incomprehensible. Col. Richard Irving Dodge reported that during a spring migration, buffalo would move north in a single column perhaps fifty miles wide. Dodge claims he was forced to climb Pawnee Rock (Kansas) to escape the migrating animals. When he looked across, the prairie was “covered with buffalo for ten miles in each direction.”

In 1806, Lewis and Clark, one of the earliest explorers to encounter the massive herds gave an ominous warning. “The moving multitude darkened the whole plains,” Clark relayed.

The sound of the migrating herd was just as impressive as the numbers. The bulky animals each weighed close to a ton each, so when they all galloped, the ground shook. “They made a roar like thunder,” wrote a first settler along the Arkansas River.

The large groupings, however, made it easier to strike them down. And when the killing started, it didn’t stop. In 1874, when Dodge returned to the prairie, he saw more hunters than buffalo. “Every approach of the herd to water was met with gunfire,” he recalled

Killing buffalo became a sport, even for foreigners. Connell reports that The London Times ran ad for a trip to Fort Collins and a chance to kill a buffalo for 50 guineas. Many gleefully went for the adventure, not the challenge. As Connell explains, English lords and ladies came to sit in covered wagons or railway carriages and fire at will. You couldn’t miss.

“Enterprising Yankees turned a profit collecting bones,” Connell wrote, explaining that it was the hide and bones and not the meat they were interested in. “Porous bones were shipped east to be ground as fertilizer; solid bones could be whittled into decorative trinkets – buttons, letter openers, pendants.”

Many settlers not knowing what else to do with a wayward buffalo grazing on their land, just shot it and left it for the wolves to feed. “The high plains stank with rotten meat” Dodge wrote.

“In just three years after the gun-toting Yankees arrived,” Connell soberly relates, “eight million buffalo were shot.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, they were nearly all gone.

The Native Americans killed buffalo too, but it was for survival, not sport. Nearly every part of the animal was used for food, medicine, clothing or tools. Even the tail made a good fly swatter. According to the Indians, the buffalo was the wisest and most powerful creature, in the physical sense, to walk the earth. Yet the Indians still played a part in the animal’s near extinction. Large fires were set by tribes in part to fell cottonwood trees and feed the bark to their horses. The massive infernos, some set one hundred miles wide, were necessary to clear land for new grass. Although no one is quite sure, thousands of buffalo and other animals surely perished in the process.

In contrast, Connell includes claims by early pioneers that the Indians were just as wasteful as the “white man” in killing the buffalo, leaving the dead carcasses where they lay, and extracting only the tongues to exchange for whiskey. These reports contradict that of agents stationed at reservations after government agreements were reached. James McLaughlin who was at Standing Rock in South Dakota helped organize mass buffalo killings, but only to stave off starvation, he claims.

Regardless, the difference in attitudes is what may have inflamed tensions between the “palefaces” and the natives.

Dodge claims the buffalo were shot because they were “the dullest creature of which I have any knowledge.” Dull meaning stupid in this sense. They would not run, Dodge purports. “Many would graze complacently while the rest of the herd was gunned down.” Dodge says his men would have to shout and wave their hats to drive the rest of the herd off.

So according to Dodge – and Connell’s book supports this – the buffalo were removed for meager profits and to get them out of the way of railways and advancing troops. This incensed the Indians, especially the Lakota, who in spite of their reliance on the buffalo, had more respect for the embattled “tatanka,” in a spiritual sense.

After all, in comparisons, they named their revered leaders and holy men after the beasts.

Custer knew one.

His name was Sitting Bull.

A Salute to the Long Play (LP) Microgroove Vinyl Record

By Ken Zurski

By Ken Zurski

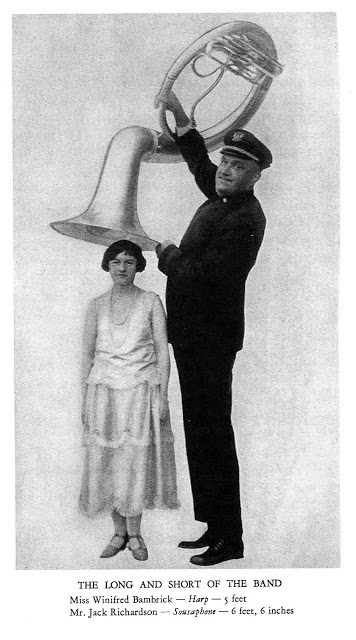

In 1948, the LP (Long Play) microgroove vinyl record was introduced by Columbia Records for the sole purpose of playing more music on a phonograph or analog sound medium. Circular in shape like its predecessors, the LP was larger in diameter at 16-inches and turned at 33 1/3 revolutions per minute, much slower than previous versions.

The LP itself was designed to replace the 12-inch records being manufactured for RCA Victor player’s in the 1930’s. The smaller plates had tighter grooves and less background noise, but unpredictable sound clarity overall.

The larger LP’s were slow to catch on at first, representing only a slight percentage of sales for consumers who were accustomed to the smaller size, faster speeds (78 rpm) and shorter play time. But as home stereo systems improved, LP’s were streamlined back to 12-inches and quickly became the preferred choice of buyers.

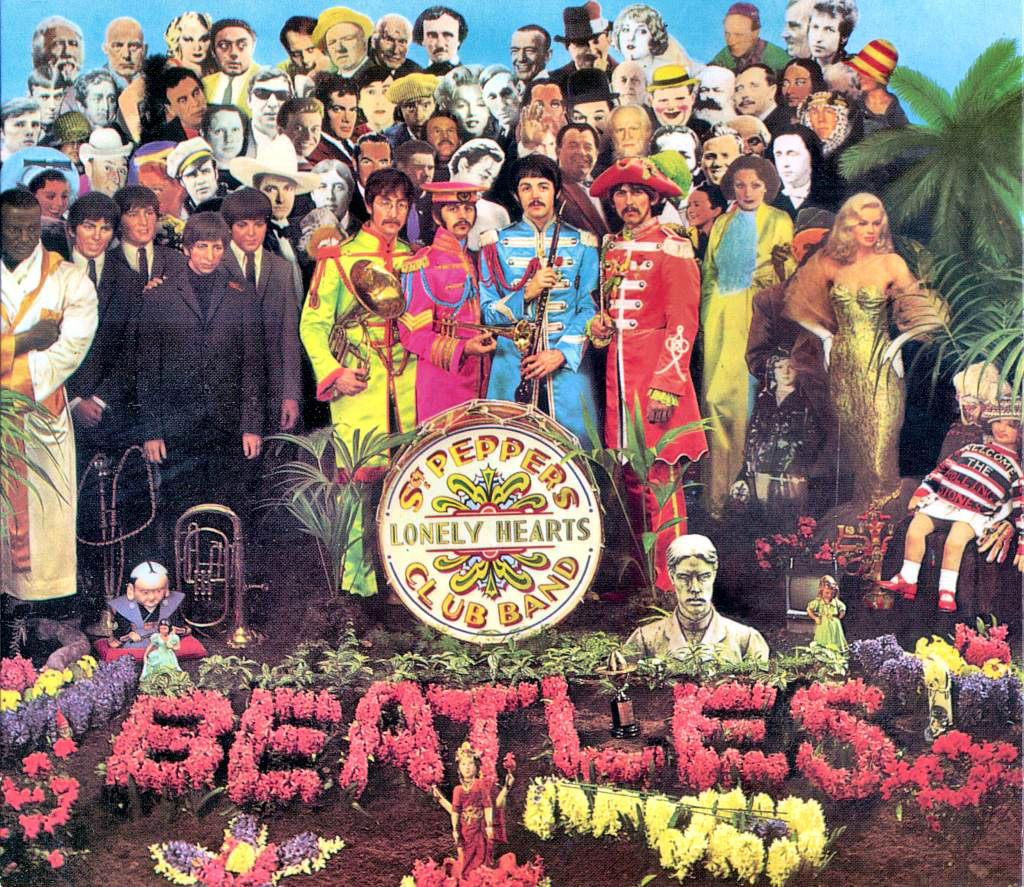

In the 1960’s and continuing into the 70’s, music artists such as the Beatles and Pink Floyd found a niche by exploiting the availability of time per LP side. They began experimenting with varying layered pieces of music, thereby making, marketing and selling albums with longer songs and conceptual themes. In some instances, two LP’s were included.

Then in the 1980’s, thanks to MTV and the demand to buy popular music, chain record stores opened in malls across America and record sales – included the smaller 45 rpm singles – continued to rise.

But it wouldn’t last.

Introduced in the mid 80’s, the new compact disc format (CD) was cheaper and less expensive to produce. The CD’s were about the same price as a vinyl album, but a CD player was costly. Eventually demand drove down the price and by the 1990’s, the age of the LP mostly disappeared. Mainstream record stores transitioned to stocking and selling only CD’s on their shelves.

Recently however, with no physical attributes attached to digital music, there’s been a surge in demand for vinyl. Newly pressed vinyl records of repackaged older and some newer music has become popular as turntables sales have increased as well. In fact according to the Recording Industry Association of America‘s midyear report for 2019, vinyl album sales may soon overtake sales of CD’s for the first time since 1986. This trend has prompted many new artists who have only produced music for the CD and digital markets to promote vinyl packaged versions of their albums as special editions.

According to c/net: “Just because vinyl may soon outpace CDs doesn’t mean music lovers are trading in their iTunes accounts for turntables. Streaming remains the most popular way to consume music, accounting for 80% of industry revenues, and growing 26%, to $4.3 billion, for the first half of 2019.”

Bu the LP just wont die. Today, original LP’s from the early 40’s to the mid 80’s are considered nostalgic and collectible. Many privately owned record shops, or independents as they are called, continue to thrive by specializing in rare or out of print editions. And online markets, swap meets and thrift stores are filled with opportunities to sell or purchase used albums.

A Salute to the Hand Salute – How Far Back Does it Go?

By Ken Zurski

In 1833, an Irish-born English artist named William Collins exhibited an oil on wood painting he appropriately titled, Rustic Civility. In the colorful image, three children are seen near a wooden gate that blocks the path of a dirt road. Collins shows the gate has been opened, presumably by the children. A boy is propped up against the open gate securing it’s place. Another smaller child cowers by the boy’s side. Yet another looks straight ahead from behind the gate.

But why and for whom did the children open the gate?

Well, that’s just a part of the painting’s mystique or as one art connoisseur wisely describes, “its puzzle.”

Upon closer inspection, however, the “puzzle” appears to be solved.

Most obvious is the shadow near the children’s feet. It is a partial outline of a horse and upon its back a rider in a brimmed hat. The children have opened the gate to make it easier for the rider, probably a stranger to them, to pass.

“People are amused at having to find out what is coming through the gate, which few do, till the shadow on the ground is pointed out to them,” the sixth Duke of Devonshire noted after buying the curious painting for his collection.

The work in some circles has been wrongly classified as a children’s picture. True, Collins would specialize in putting children in his paintings, but they were not specifically made for children. “Rustic” was part of his repertoire and a theme for several paintings including Rustic Hospitality, where friendly villagers welcome a wayward traveler who has stopped to rest near their cottage.

Today, most of Collins works are in London museums. His representations of English countryside charm in the early 19th century were very popular. Rustic Civility, however, seems to be remembered for a more significant and historical reasons. The young boy in the painting is holding his hand to his head in a gesture that closely resembles what we know today as a military salute.

A gesture not yet so easily defined at the time.

According to various sources, the origins of the hand salute goes back to medieval times when knights would salute one another by tipping their hats. Since their heads were covered with heavy and cumbersome armor, oftentimes they would just raise the visor in recognition.

In the Revolutionary War, British soldiers would remove or raise their hats in the presence of a ranking officer, an easy task since head gear at the time was used as decoration only and made of lighter material.

In subsequent wars, when soldier’s helmets became more protective the act of actually removing the head gear was too risky. A simple hand raise to the brow would suffice.

By the 20th century and during the two World Wars, saluting became more streamlined and distinctive, with the hands either palm out (the European version) or palm flat and down, the American preference.

Regardless of its history, Collins is credited at least with featuring a salute, albeit slyly, in his painting Rustic Civility. The boy appears to be “tugging his forelock,” an old-worldly expression of high regard and a gesture that suggests an early incarnation of the modern day hand to forehead signal.

This inclination of course is a matter of opinion. Perhaps, as others might suggest, the boy is just shading his eyes. After all, the location of the shadowed horse and rider puts the perspective of the sun’s light directly in the boy’s path. However, in close up, it does appear as though the boy is grabbing a lock of hair.

This clearly supports the salute theory.

Unfortunately, by the time any serious debate was raised, Collins, the artist, was dead.

So in historical context, let’s give the painter his due: To open a wooden gate while on horseback is a difficult thing to do. The children helped the man by opening the gate. The boy then saluted in deference – or civility as the title suggests.

A sign of a respect for an elder in need, Collins likely implied.

And respect is what the “salute” stands for today.

The Bee Man

By Ken Zurski

When Amos Root was a boy growing up on a farm in Medina, Ohio, instead of helping his father with the chores he stuck by his mother’s side and tended to the garden instead.

Root was small in size (only five-foot-three as an adult) and prone to sickness. The garden work suited him just fine. But in his teens, for money, Root took up jewelry as a trade and became quite good at it.

Then in 1865, at the age of 26, he found his calling – bees.

Root had offered a man a dollar if he could round up a swarm of bees outside the doors of his jewelry store. The man did and Root was hooked. But Root didn’t want to just harvest bees, he wanted to study them.

Eventually his work led to a national trade journal titled Gleaning’s in Bee Culture. Bees became his business and profitable too, but Root had other interests as well, specifically mechanical things, like the automobile, a blessing for someone who hated cleaning up after the horse. “I do not like the smell of the stables,” he once wrote.

But the automobile was different. “It never gets tired; it gets there quicker than any horse can possibly do.”

He bought an Oldsmobile Runabout, “for less than a horse” he bragged, and happily drove it near his home. Then in September 1904, at the age of 69, Root took his longest trip yet, a nearly 400-mile journey to Dayton, Ohio. Root had heard a couple of “minister’s sons” were making great strides in aviation, so he wrote them and asked if he could take a look. His enthusiasm was evident.

He bought an Oldsmobile Runabout, “for less than a horse” he bragged, and happily drove it near his home. Then in September 1904, at the age of 69, Root took his longest trip yet, a nearly 400-mile journey to Dayton, Ohio. Root had heard a couple of “minister’s sons” were making great strides in aviation, so he wrote them and asked if he could take a look. His enthusiasm was evident.

The two brothers granted his wish, but only if he promised not to reveal any secrets. In August of 1904, Root set off for his first trip to Dayton and the next month did the same. The first visit he watched in awe, but revealed nothing. The second time he was given permission to write about what he had seen. It was the first time the Wright brothers and their flying machine appeared in print.

“My dear friends,” Root gleefully wrote in his bee publication, “I have a wonderful story to tell you. “

Uncovering Manson’s Teenage Years: The Peoria Connection

By Ken Zurski

Thanks to author Jeff Guinn’s biographical book of Charles Manson, titled Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson, a few more details emerge about the notorious killer’s time as a boy, his introduction to crime, early run-ins with the law, and in particular, his short but volatile stint in the nation’s heartland, specifically Peoria, Illinois.

Sometime in the late 1940’s, Guinn explains that Manson, or “Charlie” to his friends and family, and another boy named Blackie Nielson broke out of Boys Town in Omaha, Nebraska, stole a car and drove it to Peoria where Nielson’s uncle lived.

Manson was in Boy’s Town after failing to stay at another boy’s school in Terre Haute, Indiana. His mother Kathleen insisted Charlie go to a reform school while she served prison time for a bit role in an attempted robbery masterminded by her brother Luther, Charlie’s uncle.

In Terre Haute, Manson ran away and ended up in Indianapolis where he robbed a few dime stores. He needed the money to rent a room and hide. He pushed his luck though and got caught. The sympathetic judge went easy on young Charlie. “Erroneously assuming that the boy was Catholic,” Guinn writes, “the judge sends him to Boy’s Town, the most famous juvenile facility in America.”

That would straighten him out, the judge conferred. But it didn’t work. Boy’s Town had a reputation for turning wayward boys around, but it was no prison and security was lax. Manson and his new friend, Blackie, left the grounds, hotwired a car and hightailed it to Illinois.

What happens next is fragmentary. It’s probably why Guinn spends only a few paragraphs on it. In fact the word “Peoria” isn’t even listed in the book’s index. But Manson’s time in Peoria may be just as influential on the young boy’s life as his first arrest in Indianapolis. It’s also just as surprising, considering his age. After all he was only thirteen, according to Guinn.

Guinn writes that Charlie and Blackie set out to rob a few businesses in Peoria, including a grocery store. But these “knock offs” were different. Charlie had a gun. Even Guinn’s not sure how he got it, possibly stole it from Blackie’s uncle. But how is not as important as – why? In hindsight, it’s apparent the young boy was headed towards a more complicated life of crime – even murder. But instead of ripping off a few dinky stores just to get by like he did in Indianapolis, this time Manson armed with a weapon appeared to be doing it for fun. When Manson got caught again, a Peoria judge wasn’t so lenient. He sent Charlie to a hard core reform school in Plainfield, Indiana where adult supervisors were more like drill sergeants. The rest of Manson’s youth plays out similarly – bit robberies, run-ins with the law and eventually some prison time – until we get to the 1960’s and the unfortunate reasons why he is famous today.

But that was it for Manson’s time in Peoria.

Throughout the years, a few articles in the Peoria Journal Star bulletin the arrests but offer few details. Did Manson really try to rob the Chevrolet dealership on Main Street and jump into a squad car instead of a getaway car, as the paper claims? Heady stuff, for sure. But true?

Thanks to the efforts of Peoria Journal Star columnist Phil Luciano who in 1992 wrote a letter to Manson asking: What brought you to Peoria and what did you do here? Manson wrote back as he often did to reporter’s inquiries. His answers are lucid enough, but not very descriptive or specific. Manson recalls stealing some jewelry, putting it in a safe and dumping the safe over a bridge onto railroad tracks below. “Yeah, I did a lot of growing up in that town (Peoria),” he writes in the letter, “fast growing up.”

Manson’s other recollections of Peoria makes it sound like he was in town for months, if not years (Guinn’s book isn’t clear on this. Likely, it was only for a couple of weeks). Of course, for Manson, this comes nearly 50 years after the fact. A lot more scandalous and disturbing events took place in the man’s life since then, including the murder of actress Sharon Tate and four others on August 8th and 9th, 1969.

Guinn claims that his correspondence letters from Manson were mostly ramblings about how he had been wronged and not much else. “That’s all you need to know,” Manson curtly answered one letter after offering nothing substantial in return. Apparently he didn’t like books written about him.

Manson was sentenced to life for the Tate/LeBlanco murders, incarcerated in a California State Prison, frequently denied parole, and died on November 19, 2017 at the age of 83.

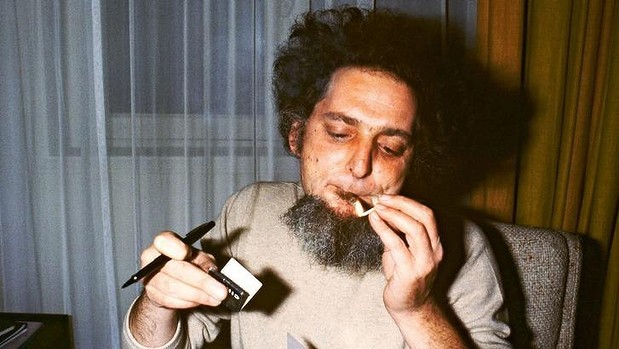

The cover of Guinn’s book shows a picture of a neatly dressed young man. He is smiling and seems content. Although his gaze is slightly off, there’s only a hint of the “crazy eyes” that his cousin’s claim Charlie possessed at times.

The more recognizable image of the convicted killer with tussled hippie-like long hair and a creepy blank stare would come later, when Manson was in his late 20’s and early thirties.

While in Illinois, Charlie was just a teenager.

As Christmas Crooners Go, Perry Como Was As ‘Pure As The Driven Snow’

By Ken Zurski

Perry Como may be the most popular Christmas performer of all time. Thanks to his long-standing annual holiday television specials and beloved Christmas album released in 1968, Como’s face and voice became synonymous with the sounds of the season.

Today, however, in a more crowded market for Christmas music and numerous more versions of favorite holiday classics (and new ones too) from more contemporary artists in all genres, Como’s versions might get lost in the mix.

But it’s still in there.

That said, as a performer, he may have been misunderstood as well.

Como was considered one of the “good guys” whose relaxed and laid-back demeanor came across as “lazy” to some, a misguided assessment, since Como was known to be a consummate professional who practiced and rehearsed incessantly.

“No performer in our memory rehearses his music with more careful dedication than Como.” a music critic once enthused.

Como also made sure each concert met his own personal and strict moral standards.

In November 1970, Como hosted a concert in Las Vegas, a comeback of sorts for the Christmas crooner, who hadn’t played a Vegas night club for over three decades. For his grand return, Como was paid a whopping $125-thousand a week, admittedly a large sum for a Vegas act at the time. Even Perry was surprised. “It’s more money than my father ever made in a lifetime,” he remarked.

But since it was Vegas and befitting the desert town’s reputation of gambling and prostituition, Como’s reputation as a straight-laced performer was questioned.

Como quelled any concerns, however, when he chose a safe, clean and relatively unknown English comic named Billy Baxter to warm up the audience before the show. Advisers suggested he pick an act more familiar to Vegas audiences, but Como said no.

A typical “Vegas comedian,” as he put it, was simply too dirty.

Keeping up the family friendly atmosphere accentuated in his TV specials, Como would lovingly introduced his wife Roselle during the “live” shows. Roselle, who was usually backstage and acknowledged the appreciative crowds, was just as adamant as her husband that his clean-cut image went untarnished. After one performance, Roselle received a fan’s note that pleased her immensely. “Not one smutty part, not even a hint,” the note read describing Como’s act in Vegas. “You should be very proud.”

Como’s cool temperament and sleepy manner was such a recognizable and enduring characteristic that many had to ask if it was real or just an act. Does he ever get upset? was one curious inquiry. “Perry has a temper,” his orchestra leader Mitchell Ayers answered. “He loses his temper at normal things. When were’ driving, for instance, and somebody cuts him off he really lets the offender have it.” However, Ayers added, “Como is the most charming gentleman I’ve ever met.”

Como’s popular Christmas television specials ran for three decades ending in 1994, seven years before his death from symptoms of Alzheimer’s in 2001. He was 88.

(Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal Nov 21 1970)

Baseball’s ‘Eating Champion’ Story is a Little Hard to Swallow, But…

Frank “Ping” Bodie, an Italian-American major league baseball player, once said that he could out eat anyone especially when it came to his favorite dish, pasta. So on April 3 1919, in Florida during a spring training break, Bodie and an ostrich (yes, an ostrich) went head-to-head in an all out, no holds barred, eating contest.

Or did they? That’s left for history to decide.

But it makes for a great story.

As a ballplayer and an outfielder, Bodie was a serviceable player, but a bit of an instigator. He was always up for a good argument and couldn’t help talking up his own merits. ”I could whale the old apple and smack the old onion,” he said about his batting prowess. While playing for a lowly Philadelphia A’s ball club, Bodie claimed there were only two things in the city worth seeing, himself, of course, and the Liberty Bell.

I can “hemstitch the spheroid,” he boasted, apparently talking about the ball.

Despite being a a bit of a braggart, the player’s loved Bodie’s positive attitude. But his expressive candor clashed with managers and he was traded to several teams before ending up with the New York Yankees where his road mate was the irrepressible Babe Ruth. When a reporter asked Bodie what it was like to room with baseball’s larger-than-life boozer, Bodie had the perfect answer. “I room with his suitcase,” he said.

Bodie was born Francesco Stephano (anglicized to Frank Stephen) Pezzello, but most people knew him by his more baseball player sounding nickname, Ping. He claimed “Ping” was from a cousin although many wished to believe it was after the sound of the ball hitting his bat. Bodie was the name of a bustling California silver mining town that his father and uncle lived for a time.

Bodie’s reputation as a big-time eater preceded him.

While in Jacksonville, Florida for spring training, the co-owner of the Yankees, Col T.L “Cap” Huston, heard about an ostrich at the local zoo named Percy who had an insatiable appetite. Huston told Bodie and the challenge was on. Whether it actually happened as reported however is up for debate. The accounts are so wildly embellished that the truth is muddled.

But who was questioning?

Fearing backlash from animal lovers (even those who loved ostrich’s, it seemed), the match was held at a secret location. Bodie reportedly won the contest, but only after Percy, who barely finished an eleventh plate, staggered off and died. Ostrich’s eat a lot, but Percy’s untimely demise was attributed to inadvertently swallowing the timekeeper’s watch. He expired with “sides swelled and bloodshot eyes.” one writer related.

For anyone who believed that, the rest of the story was easy to digest. Bodie finished a twelfth plate of pasta and claimed the self-appointed title of “spaghetti eating champion of the world.”.

The next day, Bodie was in the newspaper for serving up a double play ball in the eighth inning and helping rival Brooklyn Dodgers secure a “slaughter” of the Yankees, 11-2.

There was no mention of the dead bird.

- ← Previous

- 1

- …

- 5

- 6

- 7

- Next →